Zebra

| Zebra | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

|

Equus zebra |

Zebra is the common name for various wild, horse-like odd-toed ungulates (Order Perissodactyla) of the family Equidae and the genus Equus, native to eastern and southern Africa and characterized by distinctive white and black (or brown) stripes that come in different patterns unique to each individual. Among the other living members of the Equus genus are horses, donkeys, Przewalski's horse (a rare Asian species), and hemionids (Onager or Equus hemionus).

There are four extant species of zebra. The plains zebra (Equus quagga), Grevy's zebra (Equus grevyi), Cape mountain zebra (Equus zebra) and the Hartmann's mountain zebra (Equus hartmannae). The Cape mountain zebra and Hartmann's mountain zebra are sometimes treated as the same species.

In reality, the term zebra does not describe any specific taxon and is used to refer to black and white-striped members of the family Equidae. All extant members of the family are of the genus Equus, but the genus is commonly subdivided into four subgenera: Equus, Asinus, Hippotigris, and Dolichohippus. The plains zebra and the two species of mountain zebras belong to Hippotigris, but the Grevy's zebra is the sole species of Dolichohippus. In many respects, it is more akin to the asses (Asinus), while the other zebras are more closely related to the horses (Equus). In certain regions of Kenya, the plains zebras and Grevy's zebras coexist.

The unique stripes and behaviors of zebras make these among the most familiar animals to people, while ecologically, zebras are integral to various food chains, converting plant matter into biomass for large predators. However, various anthropogenic factors have severely impacted zebra populations, in particular hunting for skins and habitat destruction. Grevy's zebra and both mountain zebras are endangered, with the Cape mountain zebra hunted to near extinction by the 1930s, when its population was less than 100 individuals, although it has since recovered. While the plains zebras are much more plentiful, one subspecies, the quagga, went extinct in the late nineteenth century.

The pronunciation is (IPA): /ˈzɛbrə/ (ZEB-ra) in the United Kingdom or (IPA): /ˈziːbrə/ (ZEE-bra) in North America.

Species

Currently, four extant species of zebras, as well as several subspecies, have been delineated.

Prior to 2004, it was held that there were three extant species, with the Cape mountain zebra (Equus zebra zebra) and Hartmann's mountain zebra (Equus zebra harmannea) generally treated as subspecies of one mountain zebra species. In 2004, C. P. Groves and C. H. Bell investigated the taxonomy of the genus Equus, subgenus Hippotigris, and concluded that the Cape mountain zebra and Hartmann's mountain zebra are totally distinct, and suggested that the two taxa are better classified as separate species, Equus zebra and Equus hartmannae. Thus, two distinct species of mountain zebra are commonly recognized today. The other zebra species are the plains zebra, Equus quagga, and Grevy's zebra, Equus grevyi.

Zebra populations vary a great deal, and the relationships between and the taxonomic status of several of the subspecies are well known.

- Plains zebra, Equus quagga

- Cape mountain zebra, Equus zebra

- Hartmann's mountain zebra, Equus hartmannae

- Grevy's zebra, Equus grevyi

Plains zebra. The plains zebra (Equus quagga, formerly Equus burchelli), also known as the common zebra or the Burchell's zebra, is the most common and geographically widespread form of zebra, once being found from the south of Ethiopia right through east Africa as far south as Angola and eastern South Africa. The plains zebra is much less numerous than it once was because of human activities such as hunting it for its meat and hide, as well as encroachment on much of its former habitat, but it remains common in game reserves. It includes the quagga, an extinct subspecies, Equus quagga quagga.

Grevy's zebra. Grevy's zebra (Equus grevyi), sometimes known as the imperial zebra, is the largest species of zebra and has an erect mane and a long, narrow head making it appear rather mule-like. It is an inhabitant of the semi-arid grasslands of Ethiopia and northern Kenya. Compared to other zebras, it is tall, has large ears, and its stripes are narrower. The species is named after Jules Grévy, a president of France, who, in the 1880s, was given one by the government of Abyssinia. Grevy's zebra differs from all other zebras in its primitive characteristics and different behavior. Grevy's zebra is one of the rarest species of zebra around today, and is classified as endangered.

Cape mountain zebra. The Cape mountain zebra, Equus zebra, can be found in the southern Cape, South Africa. They mainly eat grass but if little food is left they will eat bushes. Groves and Bell found that the Cape mountain zebra exhibits sexual dimorphism, with larger females than males, while Hartmann's mountain zebra does not.

Hartmann's mountain zebra. Hartmann's mountain zebra can be found in coastal Namibia and southern Angola. Hartmann's mountain zebras prefer to live in small groups of 7–12 individuals. They are agile climbers and are able to live in arid conditions and steep mountainous country. The black stripes of Hartmann's mountain zebra are thin with much wider white interspaces, while this is the opposite in Cape mountain zebra.

Although zebra species may have overlapping ranges, they do not interbreed. This held true even when the quagga and Burchell's race of plains zebra shared the same area. According to MacClintock and Mochi (1976), Grevy's zebras have 46 chromosomes; plains zebras have 44 chromosomes, and mountain zebras have 32 chromosomes. In captivity, plains zebras have been crossed with mountain zebras. The hybrid foals lacked a dewlap and resembled the plains zebra apart from their larger ears and their hindquarters pattern. Attempts to breed a Grevy's zebra stallion to mountain zebra mares resulted in a high rate of miscarriage.

Physical attributes

Stripes

Zebras are characterized by black (or brown) and white stripes and bellies that have a large white blotch, apparently for camouflage purposes (Gould 1983). The hair is pigmented, not the skin (Wingert 1999). It is hypothesized that zebras are fundamentally dark animals with areas where the pigmentation is inhibited, based on the fact that (1) white equids would not survive well in the African plains or forests; (2) the quagga, an extinct plains zebra subspecies, had the zebra striping pattern in the front of the animal, but had a dark rump; and (3) secondary stripes emerge when the area between the pigmented bands is too wide, as if suppression was weakening (Wingert 1999). The fact that zebras have white bellies is not very strong evidence for a white background, since many animals of different colors have white or light colored bellies (Wingert 1999).

The stripes are typically vertical on the head, neck, forequarters, and main body, with horizontal stripes at the rear and on the legs of the animal. The "zebra crossing" is named after the zebra's white and black stripes.

Zoologists believe that the stripes act as a camouflage mechanism. This is accomplished in several ways (HSW). First, the vertical striping helps the zebra hide in grass. While seeming absurd at first glance considering that grass is neither white nor black, it is supposed to be effective against the zebra's main predator, the lion, which is colorblind. Theoretically, a zebra standing still in tall grass may not be noticed at all by a lion. Additionally, since zebras are herd animals, the stripes may help to confuse predators—a number of zebras standing or moving close blend together, making it more difficult for the lion to pick out any single zebra to attack (HSW). A herd of zebras scattering to avoid a predator will also represent to that predator a confused mass of vertical stripes traveling in multiple directions making it difficult for the predator to track an individual visually as it separates from its herdmates, although biologists have never observed lions appearing confused by zebra stripes.

Stripes are also believed to play a role in social interactions, with slight variations of the pattern allowing the animals to distinguish between individuals.

A more recent theory, supported by experiment, posits that the disruptive coloration is also an effective means of confusing the visual system of the blood-sucking tsetse fly (Waage 1981). Alternative theories include that the stripes coincide with fat patterning beneath the skin, serving as a thermoregulatory mechanism for the zebra, and that wounds sustained disrupt the striping pattern to clearly indicate the fitness of the animal to potential mates.

Senses

Zebras have excellent eyesight with binocular-like vision. It is believed that they can see in color. Like most ungulates, the zebra has its eyes on the sides of its head, giving it a wide field of view. Zebras also have night vision although it is not as advanced as that of most of their predators.

Zebras have great hearing, and tend to have larger, rounder ears than horses. Like horses and other ungulates, zebra can turn their ears in almost any direction. Ear movement can also signify the zebra's mood. When a zebra is in a calm or friendly mood, its ears stand erect. When it is frightened, its ears are pushed forward. When angry, the ears are pulled backward.

In addition to eyesight and hearing, zebra have an acute sense of smell and taste.

Ecology and behavior

Zebras can be found in a variety of habitats, such as grasslands, savanna, woodlands, thorny scrublands, mountains, and coastal hills.

Like horses, zebras walk, trot, canter, and gallop. They are generally slower than horses but their great stamina helps them outpace predators, especially lions which get tired rather quickly. When chased, a zebra will zig-zag from side to side making it more difficult for the predator. When cornered the zebra will rear up and kick its attacker. A kick from a zebra can be fatal. Zebras will bite their attackers as well.

Social behavior

Like most members of the horse family, zebras are highly sociable. Their social structure, however, depends on the species. Mountain zebras and plains zebras live in groups consisting of one stallion with up to six mares and their foals. A stallion forms a harem by abducting young mares from their families. When a mare reaches sexual maturity, she will exhibit the estrous posture, which invites the males. However she is usually not ready for mating at this point and will hide in her family group. Her father has to chase off stallions attempting to abduct her. Eventually a stallion will be able defeat the father and include the mare into his harem.

A stallion will defend his group from bachelor males. When challenged, the stallion would issue a warning to the invader by rubbing nose or shoulder with him. If the warning is not heeded, a fight breaks out. Zebra fights often become very violent, with the animals biting at each other's necks or legs and kicking.

While stallions may come and go, the mares stay together for life. They exist in a hierarchy with the alpha female being the first to mate with the stallion and being the one to lead the group.

Unlike the other zebra species, Grevy's zebras do not have permanent social bonds. A group of these zebras rarely stays together for more than a few months. The foals stay with their mother, while the adult male lives alone.

Like horses, zebras sleep standing up and only sleep when neighbors are around to warn them of predators. When attacked by packs of hyenas or wild dogs, a plains zebra group will huddle together with the foals in the middle while the stallion tries to ward them off. Zebra groups often come together in large herds and migrate together along with other species such as blue wildebeests. Zebras communicate with each other with high-pitched barks and brays.

Food and foraging

Zebras are very adaptable grazers. They feed mainly on grasses but will also eat shrubs, herbs, twigs, leaves, and bark. Plains zebras are pioneer grazers and are the first to eat at well-vegetated areas. After the area is mowed down by the zebras, other grazers follow.

Reproduction

Like most animal species, female zebras mature earlier than the males and a mare may have her first foal by the age of three. Males are not able to breed until the age of five or six. Mares may give birth to one foal every twelve months. She nurses the foal for up to a year. Like horses, zebras are able to stand, walk, and suckle shortly after they are born. A zebra foal is brown and white instead of black and white at birth. Plains and mountain zebra foals are protected by their mother as well as the head stallion and the other mares in their group. Grevy’s zebra foals have only their mother. Even with parental protection, up to 50 percent of zebra foals are taken by predation, disease, and starvation each year.

Evolution

Zebras are considered to have been the second species to diverge from the earliest proto-horses, after the asses, around 4 million years ago. The Grevy's zebra' is believed to have been the first zebra species to emerge.

Zebras might have lived in North America in prehistoric times. Fossils of an ancient horse-like animal were discovered in the Hagerman Fossil Beds National Monument in Hagerman, Idaho. It was named the Hagerman horse with a scientific name of Equus simplicidens. There is some debate among paleontologists on whether the animal was a horse or a bona-fide zebra. While the animal's overall anatomy seems to be more horse-like, its skull and teeth indicate that it was more closely related to Grevy's zebra (NPS 2019). Thus, it is also called the American zebra or Hagerman Zebra.

Domestication

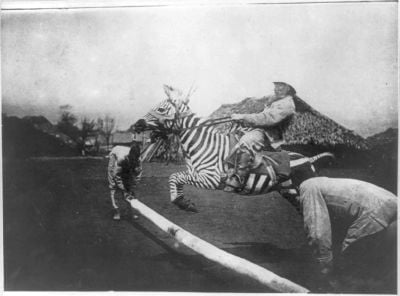

Attempts have been made to train zebras for riding since they have better resistance than horses to African diseases. However most of these attempts failed, due to the zebra's more unpredictable nature and tendency to panic under stress. For this reason, zebra-mules or zebroids (crosses between any species of zebra and a horse, pony, donkey, or ass) are preferred over pure-bred zebras.

In England, the zoological collector Lord Rothschild frequently used zebras to draw a carriage. In 1907, Rosendo Ribeiro, the first doctor in Nairobi, Kenya, used a riding zebra for house-calls.

Captain Horace Hayes, in Points of the Horse (circa 1899), compared the usefulness of different zebra species. Hayes saddled and bridled a mountain zebra in less than one hour, but was unable to give it a "mouth" during the two days it was in his possession. He noted that the zebra's neck was so stiff and strong that he was unable to bend it in any direction. Although he taught it to do what he wanted in a circus ring, when he took it outdoors he was unable to control it. He found the Burchell's zebra easy to break in and considered it ideal for domestication, as it was also immune to the bite of the tsetse fly. He considered the quagga well-suited to domestication due to being stronger, more docile, and more horse-like than other zebras.

Conservation

Modern civilization has had great impact on the zebra population since the nineteenth century. Zebras were, and still are, hunted mainly for their skins. The Cape mountain zebra was hunted to near extinction with less than 100 individuals by the 1930s. However the population has increased to about 700 due to conservation efforts. Both mountain zebra species are currently protected in national parks but are still endangered.

The Grevy's zebra is also endangered. Hunting and competition from livestock have greatly decreased their population. Because of the population's small size, environmental hazards, such as drought, are capable of easily affecting the entire species.

Plains zebras are much more numerous and have a healthy population. Nevertheless they too are threatened by hunting and habitat change from farming. One subspecies, the quagga, is now extinct.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Gould, S.J. 1983. Hen's Teeth and Horse's Toes: Further Reflections in Natural History. New York: W. W. Norton and Company. ISBN 0393017168.

- Hayes, M.H. 1893. The Points of the Horse: A Treatise on the Conformation, Movements, Breeds and Evolution of the Horse. London: Hurst and Blackett.

- How Stuff Works (HSW). How do a zebra's stripes act as camouflage? How Stuff Works. Retrieved August 11, 2021.

- MacClintock, D., and U. Mochi. 1976. A Natural History of Zebras. New York: Scribner. ISBN 0684146215.

- National Park Service (NPS). 2019. The Hagerman Horse Hagerman Fossil Beds.

- Waage, J.K. 1981. How the zebra got its stripes: Biting flies as selective agents in the evolution of zebra colouration. J. Entom. Soc. South Africa 44: 351–358.

- Wingert, J.M. 1999. Is a zebra white with black stripes or black with white stripes? MadSci Network: Zoology. Retrieved August 11, 2021.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.