Grevy's zebra

| Grévy's zebra | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| Equus grevyi Oustalet, 1882 | ||||||||||||||

Range map

|

Grévy's zebra is the common name for the largest species of zebra, Equus grevyi, characterized by large, rounded ears, erect and striped mane, and a short coat with narrow and close-set black and white stripes that extend to the hooves. Also known as the Imperial zebra, it is the largest wild member of the horse family Equidae. This odd-toed ungulate is found in Ethiopia and Kenya.

Grévy's zebra was the first zebra to be discovered by the Europeans and was used by the ancient Romans in circuses. Later, it was largely forgotten about in the Western world until the seventeenth century.

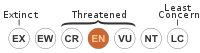

In addition to their value for aesthetic purposes or tourism, whether in the field or in zoos, Grévy's zebras also have provided food and medicine for people. However, they are now Endangered, with a significant decline in population size and range size in recent years. This is largely due to anthropogenic factors, such as hunting, habitat loss, and competition with livestock and humans for forage and water. Their decline also has reduced their ecological function. Whereas they once were very important herbivores in arid and semi-arid grasslands and shrublands, their population size is now below about 2,500 individuals in their native habitat.

Overview and description

Gr√©vy's zebra (Equus grevyi) is a member of the Equidae, a family of odd-toed ungulate mammals of horses and horse-like animals. There are three basic groups recognized in Equidae‚ÄĒhorses, asses, and zebras‚ÄĒalthough all extant equids are in the same genus of Equus.

Grévy's zebra is one of three or four extant species of zebras. The other extant species are the plains zebra (E. quagga), the Cape mountain zebra (Equus zebra) and the Hartmann's mountain zebra (E. hartmannae), which are placed together in the subgenus Hippotigris. The Cape mountain zebra and Hartmann's mountain zebra are sometimes treated as the same species. Grévy's zebra (E. grevyi) is placed in its own subgenus of Dolichohippus. In many respects, it is more akin to the asses (subgenus Asinus), while the other zebras are more closely related to the horses (subgenus Equus). Nevertheless, DNA and molecular data show that zebras do indeed have monophyletic origins. In certain regions of Kenya, the plains zebras and Grevy's zebras coexist.

Grévy's zebra differs from the other two zebras in its primitive characteristics and different behavior. Compared to other zebras, Grévy's zebra is tall, has large ears, and its stripes are narrower. It was the first zebra to emerge as a species.

Grévy's zebra is the largest of all wild equines. It is 2.5 to 3.0 meters (8-9.8 feet) from head to tail with a 38 to 75 centimeter (15-30 inch) tail, and stands 1.45 to 1.6 meters (4.6-5.25 feet) high at the shoulder. These zebras weigh 350 to 450 kilograms (770-990 pounds). The stripes are narrow and close-set, being broader on the neck, and they extend to the hooves. The belly and the area around the base of the tail lack stripes. With all of the stripes closer together and thinner than most of the other zebras, it is easier to make a good escape and to hide from predators. The ears are very large, rounded, and conical. The head is large, long, and narrow, particularly mule-like in appearance. The mane is tall and erect; juveniles having a mane extending the length of the back.

The species is named after Jules Grévy, a president of France, who, in the 1880s, was given one by the government of Abyssinia.

Distribution and habitat

Grévy's zebra is limited to the Ethiopia and Kenya in the Horn of Africa, although it is possible they also persist in Sudan. They have gone one of the most substantial range reductions of any mammal in Africa and are considered extinct in Somalia (the last sighting in 1973) and Dijibouti. Grévy's zebras live in arid and semi-arid grasslands and shrublands, where permanent water can be found (Moehlman et al. 2008).

As of 2008, there are estimated to be between 1,966 and 2,447 animals left in total. The population is believed to have declined about 55 percent from 988 and 2007, with a worse case scenario of a decline of 68 percent from 1980 to 2007. In Kenya the species declined from about 4,276 in 1988 to 2,435-2,707 in 2000 to 1,567-1,976 in 2004, while in Ethiopia it declined from 1,900 in 1980 to 577 in 1995 to just 106 in 2003. The largest subpopulation is about 255 individuals and the number of mature individuals, as of 2008, is about 750 (Moehlman et al. 2008).

Behavior, diet, and reproduction

Grévy's zebras are primarily grazers that feed mostly on grasses. However, during times of drought or in areas that have been overgrazed, they can browse, with browsing comprising up to thirty percent of their diet (Moehlman et al. 2008). In addition to grass, they will eat fruit, shrubs, and bark. They may spend 60 to 80 percent of their days eating, depending on the availability of food. Their well adapted digestive system allows them to subsist on diets of lower nutritional quality than that necessary for herbivores. Also, Grévy's zebras require less water than other zebras.

Grévy's zebra is similar to the ass in many ways. Behaviorally, for example, it has a social system characterized by small groups of adults associated for short time periods of a few months. Adult males spend their time mostly alone in territories of two to 12 km², which is considerably smaller than the territories of the wild asses. However, this is when breeding males are defending resource territories; non-territorial individuals may have a home range of up to 10,000 km² (Moehlman et al. 2008). The social structure of Grévy's zebra is well-adapted for the dry and arid scrubland and plains that it primarily inhabits, in contrast to the more lush habitats used by the other zebras. They are very mobile and travel over long distances, moving more than 80 kilometers, although lactating females can only go for a day or two away from water (Moehlman et al. 2008).

The territories are marked by dung piles and females who wander within the territory mate solely with the resident male. Small bachelor herds are known. Like all zebras and asses, males fight among themselves over territory and females. The species is vocal during fights (an asinine characteristic), braying loudly. However unlike other zebras, territory holding Grévy's zebra males will tolerate other males who wander in their territory possibly because non-resident males do not try to mate with the resident male's females nor interfere in his breeding activities.

Grévy's zebras mate year-round. Gestation of the zebra lasts 350 to 400 days, with a single foal being born. A newborn zebra will follow anything that moves and thus new mothers are highly aggressive towards other mares a few hours after they give birth. This prevents the foal from imprinting another female as its mother. To adapt to an arid lifestyle, Grévy's zebra foals take longer intervals between suckling bouts and do not drink water until they are three months old. They also reach independence from the mare sooner than other equids.

Status and threats

Grévy's zebra is considered Endangered, having been estimated to have declined by more than fifty percent over the past 18 years, and with a total current population of about 750 mature individuals and less than 2,500 individuals in total. One threat to the species is hunting for its skin, which fetches a high price on the world market. Its also suffers habitat destruction, human disturbances at water holes, and competition with domestic grazing animals. Less than 0.5 percent of the range of the species is protected area (Moehlman et al. 2008). They are, however, common in captivity.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Becker, C.D., and J.R. Ginsberg. 1990. Mother-infant behavior of wild Grévy's zebra: Adaptations for survival in semi-desert East Africa. Animal Behaviour 40(6): 1111-1118.

- Duncan, P. (ed.). 1992. Zebras, Asses, and Horses: An Action Plan for the Conservation of Wild Equids. IUCN/SSC Equid Specialist Group. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN.

- Grzimek, B., D.G. Kleiman, V. Geist, and M.C. McDade, Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia. Detroit: Thomson-Gale, 2004. ISBN 0307394913.

- Moehlman, P.D., Rubenstein, D.I., and F. Kebede. 2008. Equus grevyi In IUCN 2008. 2008 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved February 7, 2009.

- Prothero, D.R., and R.M. Schoch. 2002, Horns, Tusks, and Flippers: The Evolution of Hoofed Mammals. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0801871352.

- Walker, E.P., R.M. Nowak, and J.L. Paradiso. 1983. Walker's Mammals of the World. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0801825253.

External links

All links retrieved June 20, 2024.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.