Dark romanticism

Dark romanticism is a literary subgenre that emerged from the Transcendental philosophical movement popular in nineteenth-century America. Transcendentalism began as a protest against the general state of culture and society at the time, and in particular, the state of intellectualism at Harvard and the doctrine of the Unitarian church, which was taught at Harvard Divinity School. Among Transcendentalists' core beliefs was an ideal spiritual state which "transcends" the physical and empirical and is only realized through the individual's intuition, rather than through the doctrines of established religions. Prominent Transcendentalists included Sophia Peabody, the wife of Nathaniel Hawthorne, one of the leading dark romanticists. For a time, Peabody and Hawthorne lived at the Brook Farm Transcendentalist utopian commune.

Works in the dark romantic spirit were influenced by Transcendentalism, but did not entirely embrace the ideas of Transcendentalism. Such works are notably less optimistic than Transcendental texts about mankind, nature, and divinity.

Origin

The term dark romanticism comes from both the pessimistic nature of the subgenre's literature and the influence it derives from the earlier Romantic literary movement. Dark Romanticism's birth, however, was a mid-nineteenth-century reaction to the American Transcendental movement. Transcendentalism originated in New England among intellectuals like Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and Margaret Fuller and found wide popularity from 1836 through the late 1840s.[1] The movement came to have influence in a number of areas of American expression, including its literature, as writers growing up in the Transcendental atmosphere of the time were affected.[2] Some, including Poe, Hawthorne and Melville, found Transcendental beliefs far too optimistic and egotistical and reacted by modifying them in their prose and poetry‚Äďworks that now comprise the subgenre that was Dark Romanticism.[3] Authors considered most representative of dark romanticism are Edgar Allan Poe, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Herman Melville,[4] poet Emily Dickinson and Italian poet Ugo Foscolo.

Characteristics

While Transcendentalism influenced individual Dark Romantic authors differently, literary critics observe works of the subgenre to break from Transcendentalism’s tenets in a few key ways. Firstly, Dark Romantics are much less confident about the notion perfection is an innate quality of mankind, as believed by Transcendentalists. Subsequently, Dark Romantics present individuals as prone to sin and self-destruction, not as inherently possessing divinity and wisdom. G.R. Thompson describes this disagreement, stating while Transcendental thought conceived of a world in which divinity was immanent, "the Dark Romantics adapted images of anthropomorphized evil in the form of Satan, devils, ghosts … vampires, and ghouls."[5]

Secondly, while both groups believe nature is a deeply spiritual force, Dark Romanticism views it in a much more sinister light than does Transcendentalism, which sees nature as a divine and universal organic mediator. For these Dark Romantics, the natural world is dark, decaying, and mysterious; when it does reveal truth to man, its revelations are evil and hellish. Finally, whereas Transcendentalists advocate social reform when appropriate, works of Dark Romanticism frequently show individuals failing in their attempts to make changes for the better. Thompson sums up the characteristics of the subgenre, writing:

Fallen man's inability fully to comprehend haunting reminders of another, supernatural realm that yet seemed not to exist, the constant perplexity of inexplicable and vastly metaphysical phenomena, a propensity for seemingly perverse or evil moral choices that had no firm or fixed measure or rule, and a sense of nameless guilt combined with a suspicion the external world was a delusive projection of the mind‚ÄĒthese were major elements in the vision of man the Dark Romantics opposed to the mainstream of Romantic thought.[6]

Relation to Gothic fiction

Popular in England during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, Gothic fiction is known for its incorporation of many conventions that are also found in Dark Romantic works. Gothic fiction originated with Horace Walpole's The Castle of Otranto in 1764.[7] Works of the genre commonly aim to inspire terror, including through accounts of the macabre and supernatural, haunted structures, and the search for identity; critics often note Gothic fiction's "overly melodramatic scenarios and utterly predictable plots." In general, with common elements of darkness and the supernatural, and featuring characters like maniacs and vampires, Gothic fiction is more about sheer terror than Dark Romanticism's themes of dark mystery and skepticism regarding man. Still, the genre came to influence later Dark Romantic works, particularly some of those produced by Poe.[7]

Earlier British authors writing within the movement of Romanticism such as Lord Byron, Samuel Coleridge, Mary Shelley, and John Polidori who are frequently linked to gothic fiction are also sometimes referred to as Dark Romantics. Their tales and poems commonly feature outcasts from society, personal torment, and uncertainty as to whether the nature of man will bring him salvation or destruction.

Notable authors

Many consider American writers Edgar Allan Poe, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Herman Melville to be the major Dark Romantic authors.

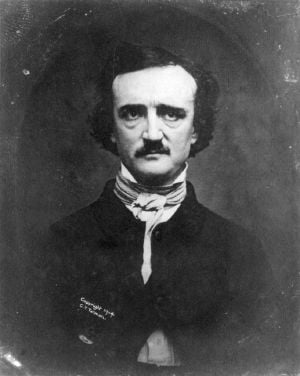

Edgar Allan Poe

Many consider Edgar Allan Poe to be the seminal dark romantic author. Many of his works are generally considered part of the genre.[8] Poe strongly disliked Transcendentalism.[9] He referred to followers of the movement as "Frogpondians" after the pond on Boston Common.[10] and ridiculed their writings as "metaphor-run," lapsing into "obscurity for obscurity's sake" or "mysticism for mysticism's sake."[11] Poe once wrote in a letter to Thomas Holley Chivers that he did not dislike Transcendentalists, "only the pretenders and sophists among them."[12]

Much of his poetry and prose features his characteristic interest in exploring the psychology of man, including the perverse and self-destructive nature of the conscious and subconscious mind.[13] Some of Poe’s notable dark romantic works include the short stories "Ligeia" and "The Fall of the House of Usher" and poems "The Raven" and "Ulalume."

His most recurring themes deal with questions of death, including its physical signs, the effects of decomposition, concerns of premature burial, the reanimation of the dead, and mourning.[14]

Herman Melville

Best known during his lifetime for his travel books, a twentieth-century revival in the study of Herman Melville‚Äôs works has left ‚ÄúMoby-Dick‚ÄĚ and ‚ÄúBartleby the Scrivener‚ÄĚ among his most highly regarded. Also known for writing of man's blind ambition, cruelty, and defiance of God, his themes of madness, mystery, and the triumph of evil over good in these two works make them notable examples of the dark romanticism sub-genre.

As Melville matured he began to use the fictional form to probe metaphysical and psychological questions, culminating in his masterpiece, Moby-Dick. This long, thematically innovative novel had no precedent and can fairly be said to stand alone in its trenchant use of symbols and archetypes. The novel follows the monomaniacal quest of the sea captain Ahab for the white whale Moby-Dick, and is a figurative exploration of the author's tortured quest to come to terms with God. According to his friend Nathaniel Hawthorne, Melville "can neither believe nor be comfortable in his unbelief."

Nathaniel Hawthorne

Nathaniel Hawthorne is the dark romantic writer with the closest ties to the American Transcendental movement. He was associated with the community in New England and even lived at the Brook Farm Transcendentalist Utopian commune for a time before he became troubled by the movement; his literature later became anti-transcendental in nature.[15] Also troubled by his ancestors' participation in the Salem witch trials, Hawthorne's short stories, including "The Minister's Black Veil" and "Mudkips of Fire"," frequently take the form of "cautionary tales about the extremes of individualism and reliance on human beings" and hold that guilt and sin are qualities inherent in man.[16]

Like Melville, Hawthorne was preoccupied with New England's religious past. For Melville, religious doubt was an unspoken subtext to much of his fiction, while Hawthorne brooded over the Puritan experience in his novels and short stories. The direct descendant of John Hawthorne, a presiding judge at the Salem witch trials in 1692, Hawthorne struggled to come to terms with Puritanism within his own sensibility and as the nation expanded geographically and intellectually.

Prominent examples

Elements contained within the following literary works by Dark Romantic authors make each representative of the subgenre:

- "Tell-Tale Heart" (1843) by Edgar Allan Poe

- "The Birth-Mark" (1843) by Nathaniel Hawthorne

- "The Minister's Black Veil" (1843) by Nathaniel Hawthorne

- Moby-Dick (1851) by Herman Melville

- "Bartleby the Scrivener" (1856) by Herman Melville

- "Ligeia" (1838) by Edgar Allan Poe

- "The Fall of the House of Usher" (1839) by Edgar Allan Poe

- "Dream-Land" (1844) by Edgar Allan Poe

- "The Raven" (1845) by Edgar Allan Poe

- "Ulalume" (1847) by Edgar Allan Poe

Legacy

The Dark romantic authors represented a response to the optimism of the ideology of Transcendentalism. While Transcendentalism focused on the individual, eschewing reason for spiritual intuition and asserting that God already exists in the individual, the Dark romantics took a somewhat dimmer view of the essential goodness of human nature. They focused on the dark side of the soul, the reality of evil and sin in the human heart, undercutting the optimistic worldview of the Transcendentalists.

The legacy of the Dark romantics can be found in a variety of media. From early in its inception, the film industry created the vampire and horror film genres in such works as Nosferatu (1922) and "The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari" (1920). These have spawned an entire genre. Another genre that was deeply influenced by Dark romanticism was the graphic novels, originating with the Batman comics in the 1930s.

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ David Galens, (ed.), Literary Movements for Students Vol. 1. (Detroit: Thompson Gale, 2002), 319.

- ‚ÜĎ David S. Reynolds, Beneath the American Renaissance: The Subversive Imagination in the Age of Emerson and Melville. (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1988. ISBN 0674065654), 524

- ‚ÜĎ G.R. Thompson, (ed.) "Introduction: Romanticism and the Gothic Tradition." Gothic Imagination: Essays in Dark Romanticism. (Pullman, WA: Washington State University Press, 1974), 6.

- ‚ÜĎ G.R. Thompson, (ed.) "Introduction: Romanticism and the Gothic Tradition." Gothic Imagination: Essays in Dark Romanticism. (Pullman, WA: Washington State University Press, 1974), 5.

- ‚ÜĎ 7.0 7.1 The Romantic Period: Topics, The Gothic: Overview. Retrieved February 19, 2009.

- ‚ÜĎ Donald N. Koster, "Influences of Transcendentalism on American Life and Literature," Literary Movements for Students Vol. 1. ed. David Galens, (Detroit: Thompson Gale, 2002), 336.

- ‚ÜĎ Kent Ljunquist, 2002, "The poet as critic," The Cambridge Companion to Edgar Allan Poe, ed. Kevin J. Hayes. (Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521797276), 15

- ‚ÜĎ Daniel Royot, "Poe's humor," as collected in The Cambridge Companion to Edgar Allan Poe, ed. Kevin J. Hayes, (Cambridge University Press, 2002, ISBN 0521797276), 61‚Äď62.

- ‚ÜĎ Kent Ljunquist, "The poet as critic" collected in The Cambridge Companion to Edgar Allan Poe, ed. Kevin J. Hayes, (Cambridge University Press, 2002, ISBN 0521797276), 15.

- ‚ÜĎ Silverman, 169.

- ‚ÜĎ W.H. Auden, "Introduction." in Nineteenth Century Literature Criticism Vol. 1. (Detroit: Gale Research Company, 1981), 518.

- ‚ÜĎ J. Gerald Kennedy, Poe, Death, and the Life of Writing. (Yale University Press, 1987, ISBN 0300037732), 3.

- ‚ÜĎ David Galens 2002, 322.

- ‚ÜĎ Tiffany K. Wayne, "Nathaniel Hawthorne." Encyclopedia of Transcendentalism. (New York: Facts on File, Inc., 2006), 140.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Galens, David, (ed.). Literary Movements for Students. Detroit: Gale, 2002. ISBN 978-0787665197

- Hayes, Kevin J. (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Edgar Allan Poe Cambridge University Press, 2002. ISBN 0521797276

- Kennedy, J. Gerald. Poe, Death, and the Life of Writing. Yale University Press, 1987. ISBN 0300037732

- Koster, Donald N. Transcendentalism in America. Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1975. OCLC 3255408

- Levin, Harry. The Power of Blackness: Hawthorne, Poe, Melville. Ohio University Press, 1980. ISBN 0821405810

- Mullane, Janet and Robert T. Wilson, (eds.). Nineteenth Century Literature Criticism Vols. 1, 16, 24. Detroit: Gale Research, 1987. ISBN 978-0810358164

- Reynolds, David S. Beneath the American Renaissance: The Subversive Imagination in the Age of Emerson and Melville. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1988. ISBN 0674065654

- Royot, Daniel. "Poe's humor." In The Cambridge Companion to Edgar Allan Poe, edited by Kevin J. Hayes. Cambridge University Press, 2002. ISBN 0521797276

- Thompson, G.R. (ed.). Gothic Imagination: Essays in Dark Romanticism. Pullman, WA: Washington State University Press, 1974. ASIN B0000E8P95

- Wayne, Tiffany K. Encyclopedia of Transcendentalism. New York: Facts On File, 2006. ISBN 978-0816056262

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.