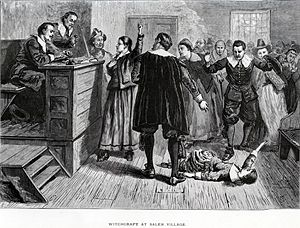

The Salem Witch Trials were a notorious episode in New England colonial history that led to the execution of 14 women and 6 men, in 1692, for charges of witchcraft. The trials began as a result of the bizarre and inexplicable behavior of two young girls, afflicted by violent convulsions and strange fits that seemingly rendered them unable to hear, speak, or see. After a medical examination and a review by Puritan clergy, the girls were judged to be victims of witchcraft. In the ensuing hysteria during the summer of 1692, nearly 200 people were accused of witchcraft and imprisoned.

Although the Salem Witch Trials are conventionally cited as an example of religious zealotry in New England, the trials were exceptional in the American colonies, with charges of witchcraft far more commonplace in Europe—particularly Germany, Switzerland, and the Low Countries—during this period. From the fourteenth to the eighteenth centuries, some 110,000 people were tried for witchcraft in Europe, and from 40,000 to 60,000 were executed. In contrast, there were only 20 executions in colonial American courts from 1647 to 1691 and the sensational trials at Salem.[1]

Modern analysis of the Salem Witch Trials regards the children's bizarre allegations and the townspeople's credulity as an example of mass hysteria, when mass public near-panic reactions surface around an unexplained phenomenon. Mass hysteria explains the waves of popular medical problems that "everyone gets" in response to news articles. A recent example of mass hysteria with remarkable similarities to the Salem Witch Trials was the rash of allegations of sexual and ritual abuse in day care centers in the 1980s and 1990s, which resulted in numerous convictions that were later overturned. Like the Salem hysteria, these allegations of sexual abuse were fueled by accusations from impressionable children who were coached by figures of authority, and resulted in destroying the lives and reputations of innocent people.

The Salem Witch Trials demonstrated the weakness of a judicial system that relied on hearsay testimony and encouraged accusations, while providing no adequate means of rebuttal. Yet, after a time conscientious magistrates did step in to stop the trials, and in subsequent years the reputations, if not the lives, of those falsely accused had been rehabilitated.

Origin of trials

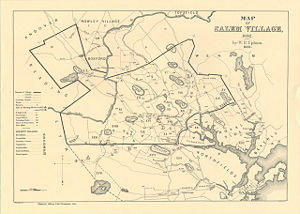

In the village of Salem in 1692, Betty Parris, age nine, and her cousin, Abigail Williams, age 11, the daughter and niece of Reverend Samuel Parris, fell victim to what was recorded as fits "beyond the power of Epileptic Fits or natural disease to effect," according to John Hale, minister in Beverly, in his book, A Modest Enquiry into the Nature of Witchcraft (1702). The girls screamed, threw things about the room, uttered strange sounds, crawled under furniture, and contorted themselves into peculiar positions. They complained of being pricked with pins or cut with knives, and when Reverend Samuel Parris would preach, the girls would cover their ears, as if dreading to hear the sermons. When a doctor, historically believed to be William Griggs, could not explain what was happening to them, he said that the girls were bewitched. Others in the village began to exhibit the same symptoms.

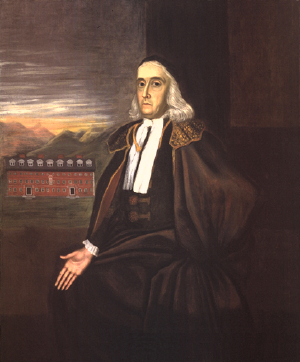

Griggs may have been influenced in his diagnosis by Cotton Mather's work, Memorable Providences Relating to Witchcrafts and Possessions (1689). In the book he describes the strange behavior exhibited by the four children of a Boston mason, John Goodwin, and attributed it to witchcraft practiced upon them by an Irish washerwoman, Mary Glover. Mather, a minister of Boston's North Church (not to be confused with the Episcopalian Old North Church of Paul Revere), was a prolific publisher of pamphlets and a firm believer in witchcraft. Three of the five judges appointed to the Court of Oyer and Terminer were friends of his and members of his congregation. He wrote to one of the judges, John Richards, supporting the prosecutions, but cautioning him of the dangers of relying on spectral evidence and advising the court on how to proceed. Mather was present at the execution of Reverend George Burroughs for witchcraft and intervened after the condemned man had successfully recited the Lord's Prayer (supposedly a sign of innocence) to remind the crowd that the man had been convicted before a jury. Mather had access to the official records of the Salem trials, upon which his account of the affair, Wonders of the Invisible World, was based.

In February of 1692, frightened by events, the residents of Salem held regular fasts and prayers for the afflicted. Wanting the influence of the devil to be removed from their community they pressured the girls into providing names. The first three people arrested for allegedly afflicting a girl by the name of Ann Putnam, age 12, were Sarah Good, a beggar, Sarah Osburne, a bedridden old woman, and Rev. Parris's slave, Tituba. Tituba was an easy and obvious target as she was a slave and of a different ethnicity than that of her Puritan neighbors. Many accounts of the history of the hysteria claim that Tituba often told witch stories and spells to the girls while she was working. However, this idea does not have much historical merit. Sarah Good was often seen begging for food. She was quick to anger and often muttered under her breath. Many people believed these mutterings to be curses that she was placing upon them. Sarah Osburne had already been marked as an outcast when she married her indentured servant. These women easily fit the mold of being different in their society, and thus were vulnerable targets. The fact that none of the three attended church also made them more susceptible to the accusations of witchcraft.

Formal charges and trial

On March 1, 1692, the three accused were held in prison and then brought before the magistrates. The women were accused of witchcraft, and soon many other women and children joined the ranks of the accused. In March, Martha Corey, Rebecca Nurse, Dorothy Good (incorrectly called Dorcas Good on her arrest warrant), and Rachel Clinton were condemned. The most outspoken of the group of women was Martha Corey. Outraged at the unjust accusations she argued that the girls who were accusing her were not to be believed. She scoffed at the trials and only brought unfavorable attention to herself in the process. Dorothy Good, Sarah Good's daughter, was only four years old when she was accused. Easily coerced into saying untrue things about her mother's behavior and her own status as a witch, she was placed in prison with her mother.

When faithful members of the Church like Martha Corey and Rebecca Nurse were accused, the community realized that anyone could be guilty of being a witch and, thus, no one was safe from the accusation. This proved true when the arrests continued during the month of April. Many more were arrested: Sarah Cloyce (Nurse's sister), Elizabeth (Bassett) Proctor and her husband John Proctor, Giles Corey (Martha's husband, and a covenanted church member in Salem Town), Abigail Hobbs, Bridget Bishop, Mary Warren (a servant in the Proctor household and sometime accuser herself), Deliverance Hobbs (step-mother of Abigail Hobbs), Sarah Wilds, William Hobbs (husband of Deliverance and father of Abigail), Nehemiah Abbott Jr., Mary Esty (sister of Cloyce and Nurse), Edward Bishop Jr. and his wife Sarah Bishop, Mary English, Lydia Dustin, Susannah Martin, Dorcas Hoar, Sarah Morey and Philip English (Mary's husband). Even Rev. George Burroughs was arrested.

The trials rested purely on testimony of those who were afflicted, or "spectral evidence." The afflicted claimed to see various apparitions or shapes of the person who was causing their pain. A theological dispute arose about the use of this kind of evidence because it was supposed that the devil could not take the shape of a person without that person's permission. The court finally concluded that the devil needed the permission of the specific person. Thus, when the accusers claimed that they had seen the person, then that person could be charged with consorting with the devil himself. Increase Mather and other ministers sent a letter to the court, "The Return of Several Ministers Consulted," urging the magistrates not to convict on spectral evidence alone. A copy of this letter was printed in Increase Mather's "Cases of Conscience," published in 1692.[2]

In May, the hysteria continued when warrants were issued for 36 more people: Sarah Dustin (daughter of Lydia Dustin), Ann Sears, Bethiah Carter Sr. and her daughter Bethiah Carter Jr., George Jacobs Sr. and his granddaughter Margaret Jacobs, John Willard, Alice Parker, Ann Pudeator, Abigail Soames, George Jacobs Jr. (son of George Jacobs Sr. and father of Margaret Jacobs), Daniel Andrew, Rebecca Jacobs (wife of George Jacobs Jr. and sister of Daniel Andrew), Sarah Buckley and her daughter Mary Witheridge, Elizabeth Colson, Elizabeth Hart, Thomas Farrar Sr., Roger Toothaker, Sarah Proctor (daughter of John and Elizabeth Proctor), Sarah Bassett (sister-in-law of Elizabeth Proctor), Susannah Roots, Mary DeRich (another sister-in-law of Elizabeth Proctor), Sarah Pease, Elizabeth Cary, Martha Carrier, Elizabeth Fosdick, Wilmot Redd, Sarah Rice, Elizabeth How, John Alden (son of John Alden and Pricilla Mullins of Plymouth Colony), William Proctor (son of John and Elizabeth Proctor), John Flood, Mary Toothaker (wife of Roger Toothaker and sister of Martha Carrier) and her daughter Margaret Toothaker, and Arthur Abbott. When the Court of Oyer and Terminer convened at the end of May 1692, this brought the total number of accused and arrested to 62.[3]

Eventually, Salem, Ipswich, Charlestown, Cambridge, and Boston all had jails filled to capacity. Scholars have attributed the lack of trials for the accused to the fact that there was no legitimate form of government at the time available to try the cases. However, it has been found that other capital cases were tried during this time period. The fact remains that none of the witchcraft cases were tried until late May with the arrival of Governor Sir William Phips. Upon his arrival, Phips instituted a Court of Oyer and Terminer (to "hear and determine") and simultaneously appointed William Stoughton as the Chief Justice of the court. Stoughton was a man with several years of theological training but no legal training. By then tragedies had already occurred, including Sarah Osborne's death before trial of natural causes. She died in jail on May 10. Sarah Good's infant child also died in jail.

Legal procedures

The process of arresting and trying an individual in 1692 began with the accusation that some loss, illness, or even death had been caused by the practice of witchcraft. The accuser entered an official complaint with the town magistrates.[4]

The magistrates would then decide if the complaint had any merit. If it did they would issue an arrest warrant.[5] The arrested person would then be brought before the magistrates and receive a public interrogations/examination. It was at this time that many were forced to confess to witchcraft.[6] If no confession was offered then the accused was turned over to the superior court. In 1692 this meant several months of imprisonment before the new governor arrived and establish a Court of Oyer and Terminer to handle these cases.

With the case appearing before the superior court, it was necessary to summon various witnesses to testify before the grand jury.[7] There were basically two indictments: That of afflicting witchcraft or that of making an unlawful covenant with the devil.[8] Once the accused was indicted the case went to trial, sometimes on the same day. An example is the case of Bridget Bishop, the first person indicted and tried, on June 2. She was executed on June 10, 1692.

The judicial environment offered those charged with witchcraft few protections against fabricated allegations. None of the accused were given the right to legal counsel, the magistrates often asked leading questions that presumed guilt, and only those who confessed were saved from execution upon conviction.[9]

The trials resulted in four execution dates: One person was executed on June 10, 1692, five were executed on July 19, another five were executed on August 19 , and eight on September 22.[10] Several others, including Elizabeth (Bassett) Proctor and Abigail Faulkner were convicted and sentenced to death, but the sentence could not be carried out immediately because the women were pregnant. The women would still be hanged, but not until they had given birth. Five other women were convicted in 1692, but sentences were never carried out: Ann Foster (who later died in prison), her daughter Mary Lacy Sr., Abigail Hobbs, Dorcas Hoar, and Mary Bradbury.

One of the men, Giles Corey, an 80-year-old farmer from Salem Farms, endured a form of torture called peine fort et dure because he refused to enter a plea. The torture was also called "pressing" and was carried out by resting a board on the man's chest and then piling stones on the board slowly until the man was slowly crushed to death. It took Corey two days to die. It was thought that perhaps Corey did not enter a plea in order to keep his possessions from being taken by the state. Many possessions of those convicted during the trials were confiscated by the state. Many of the dead were not given proper burials, often being placed in shallow graves after the hangings.

Conclusion

In early October, prominent ministers in Boston, including Increase Mather and Samuel Willard, urged Governor Phips to stop the proceedings and disallow the use of spectral evidence. Public opinion was also changing, and without the admission of spectral evidence the trials soon came to an end. The final trials during the witch hysteria took place in May of 1693, after this time, all those still in jail were set free. In a letter of explanation Phips sent to England, Phips said he stopped the trials because "I saw many innocent persons might otherwise perish."

In 1697, a Day of Repentance was declared in Boston. On that day, Samuel Sewall, a magistrate on the court, publicly confessed his "blame and shame" in a statement read by Rev. Samuel Willard, and twelve jurors who served in the trials confessed to "the guilt of innocent blood." Years later, in 1706, Ann Putnam, Jr, one of the most active accusers, stood in her pew before the Salem Village church while the Rev. Joseph Green read her confession of "delusion" by the devil.[11]

Many of the relatives and descendants of those wrongfully accused sought closure through petitions filed that demanded monetary restitution to those convicted. These petitions were filed up until 1711. Eventually, the Massachusetts House of Representatives passed a bill disallowing spectral evidence. However, only those who had initially filed petitions were given reversal of attainder.[12] This applied to only three people, who had been convicted but not executed: Abigail Faulkner Sr., Elizabeth Proctor, and Sarah Wardwell.[13]

In 1704 and 1709, another petition was filed in hopes of a monetary settlement. In 1711, a compensation of 578 pounds and 12 shillings was divided among the survivors and relatives of those accused. A sum of 150 pounds was given to the Proctor family for John and Elizabeth, by far the largest amount awarded.

In 1706, Ann Putnam, one of the girls responsible for accusing various people of witchcraft issued a written apology. In this apology, Ann stated that she had been deluded by Satan into the denouncing of several innocent people, in particular, Rebecca Nurse. In 1712, Nurse's excommunication was canceled by the very pastor who had cast her out.

By 1957, descendants of the accused were still demanding that the names of their ancestors be cleared. Finally an act was passed that pronounced all the accused as being exonerated. However, the statement only listed Ann Pudeator by name and all others were referred to as "certain other persons."

In 1992, The Danvers Tercentennial Committee persuaded the Massachusetts House of Representatives to issue a resolution honoring those who had died. The resolution was finally signed on October 31, 2001, by Governor Jane Swift. More than three hundred years after the trials, all the accused were proclaimed innocent.

Legacy

The Salem Witch Trials, although a minor incident in the far more extensive persecution of religious and social nonconformists as "witches" in Europe from the Middle Ages, is a vivid, cautionary episode in American history. Remembered largely because of its anomalous character, the trials exemplify the threat to American founding ideals of freedom, justice, and religious tolerance and pluralism. Even in New England, which accepted the reality of the supernatural, the trials at Salem were repudiated by leading Puritans. Among other clerics who expressed concern with the trials, Increase Mather wrote in "Cases of Conscience Concerning Evil Spirits" (1692) that "It were better that Ten Suspected Witches should escape, than that the Innocent Person should be Condemned."

The term "witch hunt" has entered the American lexicon to describe the search for and harassment of people or members of groups who hold politically unpopular views. It was most notably used to describe and discredit the McCarthy Hearings in the U.S. Senate in the 1950s, which sought to identify communists or communist sympathizers in government and other public positions.

The trials have also provided the background for two of America's great works of drama, the play Giles Corey in Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's New England Tragedies and Arthur Miller's classic play, The Crucible. Longfellow's play, which follows the form of a Shakespearean tragedy, is a commentary on the attitudes prevalent in nineteenth century New England. Miller's play is a commentary on the McCarthy Hearings.

Lois the Witch by Elizabeth Gaskell is a novella based on the Salem witch hunts and shows how jealousy and sexual desire can lead to hysteria. She was inspired by the story of Rebecca Nurse whose accusation, trial, and execution are described in Lectures on Witchcraft by Charles Upham, the Unitarian minister in Salem in the 1830s. Gallows Hill by Lois Duncan is a young adult fiction book in which the main character Sarah, and many others, turn out to be reincarnations of those accused and killed during the Trials. Innumerable other popular depictions, including episodes of Star Trek and the Simpsons, have led to the ongoing recognition of the Salem Witch Trials as a notable, iconic incident in American history.

Salem today

On May 9, 1992, the Salem Village Witchcraft Victims' Memorial of Danvers was dedicated before an audience of over three thousand people. It was the first such memorial to honor all of the 1692 witchcraft victims, and is located across the street from the site of the original Salem Village Meeting House where many of the witch examinations took place. The memorial serves as a reminder that each generation must confront intolerance and "witch hunts" with integrity, clear vision, and courage.[14]

The city embraces the history of the Salem Witch Trials, both as a source of tourism and culture. Police cars are adorned with witch logos, a local public school is known as the Witchcraft Heights Elementary School, the Salem High School football team is named The Witches, and Gallows Hill, a site of numerous public hangings, is currently used as a playing field for various sports.

Notes

- ↑ Kenneth Silverman, Life and Times of Cotton Mather(New York: Columbia University Press, 1985, ISBN 0231-06125-0), 89

- ↑ Increase Mather, Cases of Conscience Concerning Evil Spirits. Retrieved August 7, 2007.

- ↑ Marilynne K. Roach, The Salem Witch Trials: A Day-To-Day Chronicle of a Community Under Siege (Cooper Square Press, 2002).

- ↑ The University of Virginia, Salem Witchcraft Project 096. Retrieved August 7, 2007.

- ↑ The University of Virginia, The Salem Witchcraft Project 070. Retrieved August 7, 2007.

- ↑ The University of Virginia, Salem Witchcraft Papers from the Essex Institute 1. Retrieved August 7, 2007.

- ↑ The University of Virginia, Salem Witchcraft Project 065. Retrieved August 7, 2007.

- ↑ The University of Virginia, Salem Witchcraft Project 003. Retrieved August 7, 2007.

- ↑ West's Encyclopedia of American Law, Salem Witch Trials from Answers.com. Retrieved August 1, 2008.

- ↑ The University of Virginia, Salem Witchcraft Project 071. Retrieved August 7, 2007.

- ↑ Documentary Archive and Transcription Project, Salem Witch Trials. Retrieved August 1, 2008.

- ↑ The University of Virginia, Salem Witchcraft Project 109. Retrieved August 7, 2007.

- ↑ Enders Robinson, The Devil Discovered (2001, ISBN 1577661761).

- ↑ Salem Witch Trials Documentary Archive and Transcription Project, Salem Village Witchcraft Victims' Memorial of Danvers. Retrieved August 7, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Aronson, Marc. Witch-Hunt: Mysteries of the Salem Witch Trials. New York: Atheneum, 2003. ISBN 0689848641.

- Boyer, Paul, and Stephen Nissenbaum. Salem Possessed: The Social Origins of Witchcraft. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University, 1974. ISBN 0674785258

- Carlson, Laurie M. A Fever in Salem: A New Interpretation of the New England Witch Trials. Chicago: I.R. Dee, 1999. ISBN 1566632536.

- Godbeer, Richard. The Devil's Dominion: Magic and Religion in Early New England. New York: Cambridge University, 1992. ISBN 0521403294.

- Hansen, Chadwick. Witchcraft at Salem. New York: Brazillier, 1969.

- Hill, Frances. A Delusion of Satan: The Full Story of the Salem Witch Trials. New York: Doubleday, 1995. ISBN 0385472552.

- Karlsen, Carol F. The Devil in the Shape of a Woman: Witchcraft in Colonial New England. New York: Vintage, 1987. ISBN 0393024784.

- Reis, Elizabeth. Damned Women: Sinners and Witches in Puritan New England. Ithaca: Cornell University, 1997. ISBN 0801428343.

- Robinson, Enders A. The Devil Discovered: Salem Witchcraft 1692. New York: Hippocrene Books, 1991. ISBN 1577661761.

External links

All links retrieved December 22, 2022.

- Upham, Charles. Salem Witchcraft, Volumes I and II.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.