Cotton Mather

| Cotton Mather | |

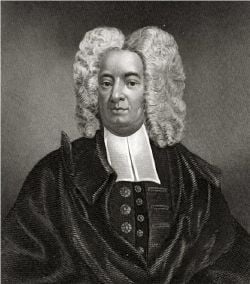

Cotton Mather, circa 1700

| |

| Born | February 12 1663 |

|---|---|

| Died | February 13 1728 (aged 65) |

| Occupation | Minister |

Cotton Mather (February 12, 1663 – February 13, 1728). A.B. 1678 (Harvard College), A.M. 1681; honorary doctorate 1710 (University of Glasgow), was a socially and politically influential Puritan minister, prolific author, and pamphleteer. Mather descended from colonial New England's two most influential families, Mather was the son of the noted Puritan divine Increase Mather (1639 – 1723) and the grandson of John Cotton and Richard Mather, both "Moses-like figures" during the exodus of English Puritans to America.

A Calvinist, Mather combined mystical recognition of an invisible spiritual world with scientific interests. A precocious intellect, Mather entered Harvard at age eleven, the youngest student ever admitted. At 18 he received his M.A. degree from his father, then president of the college. Seemingly destined for the ministry from birth, Mather was formally ordained in 1685 and joined his father in the pulpit at Boston's original North Church.

Mather was an early advocate of innoculation and corresponded extensively with notable scientists, such as Robert Boyle. Mather, like many scientists of the day and later Deists, saw the orderly laws of nature and diversity and wonder of the creation as expressions the Divine Creator. His scientific pursuits led to his acceptance into the Royal Society of London.

He is widely, perhaps inordinately remembered for his connection to the Salem witch trials. Belief in the malevolent influence of witchcraft was widespread throughout Europe and the American colonies in the seventeenth century. His affirmative support for the Salem trials, specifically his conditional acceptance of "spectral evidence," contributed to the conviction of 29 people, 19 of whom (14 women and 5 men) were executed.

Mather published more than 400 works over the course of his life. His magnum opus, Magnalia Christi Americana (1702), an ecclesiastical history of America from the founding of New England to his own time, influenced later American statesmen and religious leaders to see a divine providence in the rise of America as a refuge from European monarchal abuses and for those seeking religious freedom.

Biography

Mather was named after his grandfathers, both paternal (Richard Mather) and maternal (John Cotton). He attended Boston Latin School, and graduated from Harvard in 1678, at only 15 years of age. After completing his post-graduate work, he joined his father as assistant Pastor of Boston's original North Church (not to be confused with the Anglican/Episcopal Old North Church). It was not until his father's death, in 1723, that Mather assumed full responsibilities as Pastor at the Church.

Author of more than 450 books and pamphlets, Cotton Mather's ubiquitous literary works made him one of the most influential religious leaders in America. Mather set the nation's "moral tone," and sounded the call for second and third generation Puritans, whose parents had left England for the New England colonies of North America to return to the theological roots of Puritanism.

The most important of these, Magnalia Christi Americana (1702), is composed of seven distinct books, many of which depict biographical and historical narratives which later American writers such as Nathaniel Hawthorne, Elizabeth Drew Stoddard, and Harriet Beecher Stowe would utilize to describe the cultural significance of New England for later generations following the American Revolution. Mather's text was one of the more important documents in American history, reflecting a particular tradition of understanding the significance of place.

As a Puritan thinker and social conservative, Mather drew on the figurative language of the Bible to speak to his contemporaries. In particular, Mather's review of the American experiment sought to explain signs of his time and the types of individuals drawn to the colonies as predicting the success of the venture. From his religious training, Mather viewed the importance of texts for elaborating meaning and for bridging different moments of history (for instance, linking the Biblical stories of Noah and Abraham with the arrival of eminent leaders such as John Eliot, John Winthrop, and his own father Increase Mather).

The struggles of first, second and third-generation Puritans, both intellectual and physical, thus became elevated in the American way of thinking about its appointed place among other nations. The unease and self-deception that characterized that period of colonial history would be revisited in many forms at political and social moments of crisis (such as the Salem witch trials which coincided with frontier warfare and economic competition among Indians, French and other European settlers) and during lengthy periods of cultural definition (e.g., the American Renaissance of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century literary, visual, and architectural movements which sought to express unique American identities).

A friend of a number of the judges charged with hearing the Salem witch trials, Mather admitted the use of "spectral evidence," (compare "The Devil in New England") but warned that, though it might serve as evidence to begin investigations, it should not be heard in court as evidence to decide a case. Despite this, he later wrote in defense of those conducting the trials, stating:

"If in the midst of the many Dissatisfaction among us, the publication of these Trials may promote such a pious Thankfulness unto God, for Justice being so far executed among us, I shall Re-joyce that God is Glorified…" (Wonders of the Invisible World).

Highly influential due to his prolific writing, Mather was a force to be reckoned with in secular, as well as in spiritual, matters. After the fall of James II of England in 1688, Mather was among the leaders of a successful revolt against King James's Governor of the consolidated Dominion of New England, Sir Edmund Andros.

Mather was influential in early American science as well. In 1716, as the result of observations of corn varieties, he conducted one of the first experiments with plant hybridization. This observation was memorialized in a letter to a friend:

"My friend planted a row of Indian corn that was colored red and blue; the rest of the field being planted with yellow, which is the most usual color. To the windward side this red and blue so infected three or four rows as to communicate the same color unto them; and part of ye fifth and some of ye sixth. But to the leeward side, no less than seven or eight rows had ye same color communicated unto them; and some small impressions were made on those that were yet further off."

Of Mather's three wives and 15 children, only his last wife and two children survived him. Mather was buried on Copp's Hill near Old North Church.

Smallpox Inoculation

A smallpox epidemic struck Boston in May 1721 and continued through the year.[1]

The practice of smallpox inoculation (as opposed to the later practice of vaccination) had been known for some time. In 1706 a slave, Onesimus, had explained to Mather how he had been inoculated as a child in Africa. The practice was an ancient one, and Mather was fascinated by the idea. He encouraged physicians to try it, without success. Then, at Mather's urging, one doctor, Zabdiel Boylston, tried the procedure on his only son and two slaves–one grown and one a boy. All recovered in about a week.

In a bitter controversy, the New England Courant published writers who opposed inoculation. The stated reason for this editorial stance was that the Boston populace feared that inoculation spread, rather than prevented, the disease; however, some historians, notably H. W. Brands, have argued that this position was a result of editor-in-chief James Franklin's (Benjamin Franklin's brother) contrarian positions. Boylston and Mather encountered such bitter hostility, that the selectmen of the city forbade him to repeat the experiment.

The opposition insisted that inoculation was poisoning, and they urged the authorities to try Boylston for murder. So bitter was this opposition that Boylston's life was in danger; it was considered unsafe for him to be out of his house in the evening; a lighted grenade was even thrown into the house of Mather, who had favored the new practice and had sheltered another clergyman who had submitted himself to it.

After overcoming considerable difficulty and achieving notable success, Boylston traveled to London in 1724, published his results, and was elected to the Royal Society in 1726.

Slavery

Mather thought it his Christian duty to introduce slaves to Christianity—not an unusual view for his time. "Within his own household, two of his slaves—Onesimus, bought for Mather by his congregation in the mid 1700s, and Ezer, a servant in the 1720s—knew how to read, although we do not know who taught them. Mather even set up and paid for an evening school for blacks and Indians that lasted from at least January 1718 to the end of 1721. Significantly, Mather offered no writing instruction at this school (even though he envisioned such instruction for his own domestic slaves): the school was to instruct its students only in reading the scriptures and learning the catechism." (E.J. Monaghan) During the colonial period of America writing was not taught to the enslaved.

Cotton Mather & the Salem Witch Trials

New Englanders perceived themselves abnormally susceptible to the Devil’s influence in the seventeenth century. The idea that New Englanders now occupied the Devil’s land established this fear.[2] It would only be natural for the Devil to fight back against the pious invaders. Cotton Mather shared this general concern, and combined with New England’s lack of piety, Mather feared divine retribution. English writers, who shared Mather’s fears, cited evidence of divine actions to restore the flock.[3] In 1681, a conference of ministers met to discuss how to rectify the lack of faith. In an effort to combat the lack of piety, Cotton Mather considered it his duty to observe and record illustrious providences. Cotton Mather’s first action related to the Salem Witch Trials was the publication of his 1684 essay Illustrious Provinces.[4] Mather, being an ecclesial man believed in the spiritual side of the world and attempted to prove the existence of the spiritual world with stories of sea rescues, strange apparitions, and witchcraft. Mather aimed to combat materialism, the idea that only physical objects exist.[5]

Such was the social climate of New England when the Goodwin children received a strange illness. Mather seeing an opportunity to explore the spiritual world, attempted to treat the children with fasting and prayer.[6] After treating the children of the Goodwin family, Mather wrote Memorable Providences, a detailed account of the illness. In 1682 the Parris children received a similar illness to the Goodwin children; and Mather emerged as an important figure in the Salem Witch trials.[7] Even though Mather never presided in the jury; he exhibited great influence over the witch trials. In May 31, 1692, Mather sent a letter “Return of the Several Ministers,” to the trial. This article advised the Judges to limit the use of Spectral evidence, and recommended the release of confessed criminals.[8]

Mather as a negative influence on the trial

Critics of Cotton Mather assert that he caused the trials because of his 1688 publication Remarkable Provinces, and attempted to revive the trial with his 1692 book Wonders of the Invisible World, and generally whipped up witch hunting zeal.[9] Others have stated, “His own reputation for veracity on the reality of witchcraft prayed, ‘for a good issue.”[10] Charles Upham mentions Mather called accused witch Martha Carrier a ‘rampant hag.’[11] The critical evidence of Mather’s zealous behavior comes later, during the trial execution of George Burroughs {Harvard Class of 1670}. Upham gives the Robert Calef account of the execution of Mr. Burroughs;

“Mr. Burroughs was carried in a cart with others, through the streets of Salem, to execution. When he was upon the ladder, he made a speech for the clearing of his innocency, with such solemn and serious expressions as were to the admiration of all present. His prayer (which he concluded by repeating the Lord’s Prayer) was so well worded, and uttered with such composedness as such fervency of spirit, as was very affecting, and drew tears from many, so that if seemed to some that the spectators would hinder the execution. The accusers said the black man stood and dictated to him. As soon as he was turned off, Mr. Cotton Mather, being mounted upon a horse, addressed himself to the people, partly to declare that he (Mr. Burroughs) was no ordained minister, partly to possess the people of his guilt, saying that the devil often had been transformed into the angle of light…When he [Mr. Burroughs] was cut down, he was dragged by a halter to a hole, or grave, between the rocks, about two feet deep; his shirt and breeched being pulled off, and an old pair of trousers of one executed put on his lower parts: he was so put in, together with Willard and Carrier, that one of his hands, and his chin, and a foot of one of them, was left uncovered.”[12]

The second issue with Cotton Mather was his influence in construction of the court for the trials. Bancroft quotes Mather,

“Intercession had been made by Cotton Mather for the advancement of William Stoughton, a man of cold affections, proud, self-willed and covetous of distinction.” [13]

Later, referring to the placement of William Stoughton on the trial, which Bancroft noted was against the popular sentiment of the town.[14] Bancroft referred to a statement in Mather’s diary;

“The time for a favor is come,” exulted Cotton Mather; “Yea, the set time is come. Instead of my being a made a sacrifice to wicked rulers, my father-in-law, with several related to me, and several brethren of my own church, are among the council. The Governor of the province is not my enemy, but one of my dearest friends.”[15]

Bancroft also noted; Mather considered witches “among the poor, and vile, and ragged beggars upon Earth.”[16] Bancroft also asserted that Mather considered the people against the witch trials, ‘witch advocates.’[17]

Mather as a positive influence on the trial

Chadwick Hansen’s Witchcraft at Salem, published in 1969, defined Mather as a positive influence on the Salem Trials. Hansen considered Mathers handling of the Goodwin Children to be sane and temperate.[18] Hansen also noted that Mather was more concerned with helping the affected children than witch-hunting.[19] Mather treated the affected children through prayer and fasting.[20] Mather also tried to convert accused witch Goodwife Clover after she was accused of practicing witchcraft on the Goodwin children.[21] Most interestingly, and out of character with the previous depictions of Mather, was Mather’s decision not to tell the community of the others whom Goodwife Clover claimed practiced witch craft.[22] One must wonder if Mather desired an opportunity to promote his church through the fear of witchcraft, why he did not used the opportunity presented by the Goodwin family. Lastly, Hansen claimed Mather acted as a moderating influence in the trials by opposing the death penalty for lesser criminals, such as Tituba and Dorcas Good.[23] Hansen also notes that the negative impressions of Cotton Mather stem from his defense of the trials in, Wonders of the Invisible World. Mather became the chief defender of the trial, which diminished accounts of his earlier actions as a moderate influence.[24]

Some historians who have examined the life of Cotton Mather after Chadwick Hansen’s book share his view of Cotton Mather. For instance, Bernard Rosenthal noted that Mather often gets portrayed as the rabid witch hunter.[25] Rosenthal also described Mather’s guilt about his inability to restrain the judges during the trial.[26] Larry Gragg highlights Mather’s sympathy for the possessed, when Mather stated, “the devil have sometimes represented the shapes of persons not only innocent, but also the very virtuous.”[27] And John Demos considered Mather a moderating influence on the trial.[28]

Post-Trial

After the trial, Cotton Mather was unrepentant for his role. Of the principal actors in the trial, only Cotton Mather and William Stoughton never admitted guilt.[29] In fact, in the years after the trial Mather became an increasingly vehement defender of the trial. At the request of then Lieutenant-Governor William Stoughton, Mather wrote Wonders of the Invisible World in 1693.[30] The book contained a few of Mather’s sermons, the conditions of the colony and a description of witch trials in Europe.[31] Mather also contradicted his own advice in “Return of the Several Ministers,” by defending the use of spectral evidence. [32] Wonders of the Invisible World appeared at the same time as Increase Mather’s Case of Conscience, a book critical of the trial.[33] Upon reading Wonders of the Invisible World, Increase Mather publicly burned the book in Harvard Yard.[34] Also, Boston merchant, Robert Calef began what became an eight year campaign of attacks on Cotton Mather.[35] The last event in Cotton Mathers involvement with witchcraft was his attempt to cure Mercy Short and Margaret Rule.[36] Mather later wrote A Brand Pluck’d Out of the Burning, and Another Brand Pluckt Out of the Burning about curing the women.

Legacy

Mather's legacy is mixed. His role in the Salem witch trials remains problematic. The trials represent a blight on the pietism that was at the heart of the quest for religious freedom that characterized the Pilgrim and Puritan groups that founded the United States. The religious quest for purity had a dark side, the attempt to root out those thought to be impure from the community.

Major works

- Wonders of the Invisible World (1693) ISBN 0766168670 Online edition (PDF)

- Magnalia Christi Americana London: (1702); Harvard University Press, 1977 ISBN 0674541553

- The Negro Christianized (1706) Online edition (PDF)

- Theopolis Americana: An Essay on the Golden Street of the Holy City (1710) Online edition (pdf)

- Bonifacius: An Essay Upon the Good That Is to Be Devised and Designed (1710) ISBN 0766169243

- The Christian Philosopher (1721) ISBN 0252-068939

- Religious Improvements (1721)

- The Angel of Bethesda (1724) American Antiquarian Society, 1972. ISBN 0827172206

- Manuductio ad Ministerium: Directions for a candidate of the ministry (1726) Facsimile text society, Columbia Univ. Press (1938)

- A Token for the Children of New England (1675) (inspired by the book by James Janeway; published together with his account in the American volume) Soli Deo Gloria Publications (1997) ISBN 187761176X

- Triparadisus (1712-1726), Mather's discussion of millennialism, Jewish conversion, the Conflagration, the Second Coming, and Judgment Day

- Biblia Americana (c. 1693-1728), his unpublished commentary on the Bible An Authoritative Edition of Cotton Mather's "Biblia Americana". Holograph Manuscript, (1693-1728) Massachusetts Historical Society, General Editor: Reiner Smolinski, online, [1]

Notes

- ↑ Open Collections Program: Contagion, The Boston Smallpox Epidemic, 1721 Contagion: Historical Views of Diseases and Epidemics digital library collection, accessdate 2008-08-27

- ↑ Richard F. Lovelace. The American Pietism of Cotton Mather: Origins of American Evangelicalism. (Washington, DC: Christian College Consortium, 1979), 16}}

- ↑ Richard H. Werking, "Reformation is our only preservation: Cotton Mather and Salem Witchcraft." The William and Mary Quarterly Third Series 29 (2) (1972): 283

- ↑ Werking, 1972, 284

- ↑ Chadwick Hansen. Witchcraft at Salem. (New York: George Braziller, Inc ,1969), 27

- ↑ Hansen, 1969, 24

- ↑ Lovelace, 1979, 16

- ↑ Lovelace, 1979, 17

- ↑ Werking, 1972, 281

- ↑ George Bancroft. History of the United States of America, from the discovery of the American continent. (Boston: Little, Brown, and company, 1874-1878), 85

- ↑ Charles Upham. Salem Witchcraft. (New York: Frederick Ungar Publishing Co, 1859), 211

- ↑ Upham, 1959, 301

- ↑ Bancroft, 1874-1878, 83

- ↑ Bancroft, 1874-1878, 83

- ↑ Bancroft, 1874-1878, 84

- ↑ Bancroft, 1874-1878, 85

- ↑ Bancroft, 1874-1878, 85

- ↑ Hansen, 168

- ↑ Hansen, 60

- ↑ Hansen, 24

- ↑ Hansen, 24

- ↑ Hansen, 23

- ↑ Hansen, 123

- ↑ Hansen, 189

- ↑ Bernard Rosenthal. Salem Story. (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 169

- ↑ Rosenthal, 202

- ↑ Larry Gragg. The Salem Witch Crisis. (New York: Praeger Publishers, 1992), 88

- ↑ John Demos. Entertaining Satan: Witchcraft and the Culture of Early New England. (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2004), 305

- ↑ Bancroft, 1874-1878, 98

- ↑ Babette Levy. Cotton Mather. (Boston Twayne Publishers, 1979), 67

- ↑ Wendel D. Craker, “Spectral Evidence, Non-Spectral acts of Witchcraft, and Confessions at Salem in 1692,” The Historical Journal 40 (2)(1997): 335

- ↑ Hansen, 209

- ↑ Elaine G. Breslaw. Witches of the Atlantic World: A Historical Reader & Primary Sourcebook. (New York University Press, 2000), 455

- ↑ Lovelace, 22

- ↑ Breslaw, 455

- ↑ Lovelace, 202

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bancroft, George. History of the United States of America, from the discovery of the American continent. Boston: Little, Brown, and company, 1874-1878.

- Breslaw, Elaine G. Witches of the Atlantic World: A Historical Reader & Primary Sourcebook. New York University Press, 2000.

- Craker, Wendel D. “Spectral Evidence, Non-Spectral acts of Witchcraft, and Confessions at Salem in 1692.” The Historical Journal 40(2) (1997): 335.

- Demos, John. Entertaining Satan: Witchcraft and the Culture of Early New England. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2004(original 1982). ISBN 0195174836

- Felker, Christopher D. Reinventing Cotton Mather in the American Renaissance: Magnalia Christi Americana in Hawthorne, Stowe, and Stoddard Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1993. ISBN 155553873

- Gragg, Larry. The Salem Witch Crisis. New York: Praeger Publishers, 1992. ISBN 0275941892

- Hansen, Chadwick. Witchcraft at Salem. New York: George Braziller, Inc., 1969.

- Levy, Babbette May. Cotton Mather. Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1979. ISBN 0805772618

- Lovelace, Richard F. The American Pietism of Cotton Mather: Origins of American Evangelicalism. Grand Rapids, MI: American University Press, 1979. ISBN 0802817505

- Middlekauff, Robert. The Mathers: Three Generations of Puritan Intellectuals, 1596-1728. New York: Oxford University Press, 1971. ISBN 0520219309

- Monaghan, E. Jennifer. Learning to Read and Write in Colonial America. Worcester: American Antiquarian Society, 2005. ISBN 978-1558495814

- Rosenthal, Bernard. Salem Story: Reading the Witch Trials of 1692 (Cambridge Studies in American Literature and Culture). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1993. ISBN 0521558204

- Silverman, Kenneth. The Life and Times of Cotton Mather. New York: Harper & Row, 1984. ISBN 1566492068

- Smolinski, Reiner. "Authority and Interpretation: Cotton Mather's Response to the European Spinozists." In Shaping the Stuart World, 1603-1714: The Atlantic Connection, edited by Arthur Williamson and Allan MacInnes, 175-203. Leyden: Brill, 2006. ISBN 978-9004147119

- Smolinski, Reiner. "How to Go to Heaven, or How Heaven Goes: Natural Science and Interpretation in Cotton Mather's Biblia Americana (1690-1728)." In The New England Quarterly 81(2) (June 2008): 278-329.

- Smolinski, Reiner. The Threefold Paradise of Cotton Mather: An Edition of 'Triparadisus'. Athens; and London: University of Georgia Press, 1995. ISBN 0820315192

- Upham, Charles. Salem Witchcraft. New York: Frederick Ungar Publishing Co, 1859.

- Werking, Richard H., "Reformation is our only preservation: Cotton Mather and Salem Witchcraft." The William and Mary Quarterly Third Series 29(2) (1972): 283.

External links

All links retrieved January 10, 2024.

- Mather's influential commentary on the "Collegiate Way of Living"

- The Wonders of the Invisible World (1693 edition) in PDF format

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.