Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument

| Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument | |

|---|---|

| IUCN Category III (Natural Monument) | |

| | |

| Location: | Big Horn County, Montana, USA |

| Nearest city: | Billings, Montana |

| Area: | 765.34 acres (3,097,200 m²) |

| Established: | January 29, 1879 |

| Visitation: | 328,668 (in 2005) |

| Governing body: | National Park Service |

Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument preserves the site of the June 25, 1876 Battle of the Little Bighorn, near Crow Agency, Montana, in the United States. It also serves as a memorial to those who fought in the battle: George Armstrong Custer's 7th Cavalry and a combined Lakota-Northern Cheyenne and Arapaho force. Custer National Cemetery, on the battlefield, is part of the national monument. The site of a related military action led by Marcus Reno and Frederick Benteen is also part of the national monument, but is about 3 miles (5 km) southeast of the Little Bighorn battlefield.

Background

The 'Battle of the Little Bighorn' was one of the most famous battles of the Indian Wars. In Native American terms, it was known as the 'Battle of the Greasy Grass', while it has been more famously known among Whites as 'Custer's Last Stand'.

The battle was an armed engagement between a Lakota-Northern Cheyenne combined force and the 7th Cavalry of the United States Army. It occurred between June 25 and June 26, 1876, near the Little Bighorn River in the eastern Montana Territory.

The most famous action of the Indian Wars, it was a remarkable victory for the Lakota and Northern Cheyenne, led by Sitting Bull. A sizeable force of U.S. cavalry commanded by Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer was defeated; Custer himself was killed in the engagement along with two of his brothers.

Prelude

The Sioux controlled the northern Plains, including the Black Hills, throughout most of the nineteenth century. Paha Sapa, as the Hills were known to the Lakota Sioux, were considered sacred territory where they believe life began. The western bands of Sioux used the Hills as hunting grounds.

A series of treaties with the U.S. Government were entered into by the Allied Lakota bands at Fort Laramie, Wyoming, in 1851 and 1868. The terms of the treaty of 1868 specified the area of the Great Sioux Reservation to be all of South Dakota west of the Missouri River and additional territory in adjoining states and was to be

- "set apart for the absolute and undisturbed use and occupation" of the Lakota. [1] Further, "No white person or persons shall be permitted to settle upon or occupy any portion of the territory, or without the consent of the Indians to pass through the same." [2]

Although whites were to be excluded from the reservation, after the public discovery of gold in the 1870s, the conflict over control of the region sparked the last major Indian War on the Great Plains, the Black Hills War. Thousands of miners entered the Black Hills; by 1880, the area was the most densely populated part of Dakota Territory. Yielding to the demands of prospectors, in 1874 the U.S. government dispatched troops into the Black Hills under General George Armstrong Custer in order to establish army posts. The Sioux responded to this intrusion militarily.

The government had offered to purchase the land from the Tribe, but considering it sacred, they refused to sell. In response, the government demanded that all Indians who had left the reservation area (mainly to hunt buffalo, in line with treaty regulations) report to their agents; few complied. The U.S. Army did not keep miners off Sioux (Lakota) hunting grounds; yet, when ordered to take action against bands of Sioux hunting on the range, according to their treaty rights, the Army moved vigorously.

On June 25, 1876, after several indecisive encounters, General Custer found the main encampment of the Lakota and their allies at the Little Bighorn River. Custer and his men — who were separated from their main body of troops — were all killed by the far more numerous Indians who had the tactical advantage. They were led in the field by Crazy Horse and inspired by Sitting Bull's earlier vision of victory. This has come to be known as the "Battle of the Little Bighorn."

The battle

In the early summer months of 1876 the U.S. military officials planned a campaign to corral them and force them back to the reservations. The War Department devised an ambitious plan to be carried out by three expeditions. The plan was to converge several columns simultaneously on the Yellowstone River where the Indians would be trapped and then forced to return to their reservations.

The three expeditions involved in the northern campaign were:

- Col. John Gibbon's column of six companies, numbering about 450 men (elements of the 2d Cavalry and 7th Infantry) marched east from Fort Ellis in western Montana, patrolling the Yellowstone River to the mouth of the Bighorn.

- Brig. Gen. George Crook's column of ten companies of approximately 1,000 men (elements of the 2d and 3d Cavalry and 4th and 9th Infantry) moved north from Fort Fetterman, Wyoming, marching toward the Powder River area.

- Brig. Gen. Alfred Terry's command included in excess of 1,000 1,000 men (7th Cavalry and elements or the 6th, 17th, and 20th Infantry) moved from Fort Abraham Lincoln (North Dakota) to the mouth of Powder River.

On 17 June 1876 Crook's troops fought an indecisive engagement with a large band of Sioux and Cheyenne under Crazy Horse, Sitting Bull, and other chiefs on the Rosebud and then moved back to the Tongue River to wait for reinforcements. Meanwhile, General Terry had discovered the trail of the same Indian band and sent Lt. Col. George A. Custer with the 7th Cavalry up the Rosebud to locate the war party and move south of it. Terry, with the rest of his command, continued up the Yellowstone to meet Gibbon and close on the Indians from the north.

The 7th Cavalry, proceeding up the Rosebud, discovered an encampment of 4,000 to 5,000 Indians (an estimated 2,500 warriors) on the Little Big Horn on 25 June 1876. Custer immediately ordered an attack, dividing his forces so as to strike the camp from several directions. The surprised Indians quickly rallied and drove off Maj. Marcus A. Reno's detachment (Companies A, G, and M) which suffered severe losses. Reno was joined by Capt. Frederick W. Benteen's detachment (Companies D, H, and K) and the pack train (including Company B) and this combined force was able to withstand heavy attacks which were finally lifted when the Indians withdrew late the following day. Custer and a force of 211 men (Companies C, E, F, I, and L) were surrounded and completely destroyed. Terry and Gibbon did not reach the scene of Custer's last stand until the morning of 27 June. The 7th Cavalry's total losses in this action (including Custer's detachment) were: 12 officers, 247 enlisted men, 5 civilians, and 3 Indian scouts killed; 2 officers and 51 enlisted men wounded.

The coordination and planning went awry on June 17 when Crook's column was delayed after the Battle of the Rosebud. Surprised and, according to some accounts, astonished by the unusually large numbers of Indians faced in the battle, Crook was essentially defeated in battle and forced to stop and regroup. Unaware of Crook's situation, Gibbon and Terry proceeded, joining forces in late June near the mouth of the Rosebud River.

They formulated a plan, based on the discovery of a large Indian trail on June 15, that called for Custer's regiment to proceed up the Rosebud River, while Terry and Gibbon's united columns would move towards the Bighorn and Little Bighorn rivers. The officers planned to trap the Indian village between these two forces. The 7th Cavalry split from the remainder of the Terry column on June 22 and began a rapid pursuit along the trail.

While the Terry/Gibbon column was marching toward the mouth of the Little Bighorn, on the evening of June 24 Custer's scouts arrived at an overlook known as the Crow's Nest, 14 miles east of the Little Bighorn River. At sunrise the following day, they reported to him they could see signs of the Indian village roughly 15 miles in the distance.

Custer's initial plan was a surprise attack on the village the following morning on June 26, but a report came to him that several hostile Indians had discovered the trail left by his troops. Assuming their presence had been exposed, Custer decided to attack the village without further delay. Unbeknownst to him, this group of Indians were actually leaving the encampment on the Big Horn and did not alert the village.

Custer's scouts repeatedly warned him about the size of the village, with scout Mitch Bouyer saying, "General, I have been with these Indians for 30 years, and this is the largest village I have ever heard of." Custer's overriding concern was that the Indians would break up and scatter in different directions. The command began its approach to the village at noon and prepared to attack in full daylight. [3]

The unusually large village gathered along the banks of the Little Bighorn included Lakota, Northern Cheyenne and a small number of Arapaho. The size of the village is unknown, though is estimated to have been 949 lodges, with between 900 to 1,800 warriors.

The battle

Memorial site

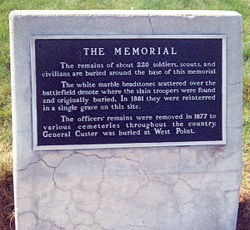

The site of the Battle of the Little Bighorn was first preserved as a national cemetery by the Secretary of War on January 29, 1879. It was named , to protect graves of the 7th Cavalry troopers buried there. Proclaimed National Cemetery of Custer's Battlefield Reservation to include burials of other campaigns and wars on December 7, 1886. The name has been shortened to "Custer National Cemetery," and although it had been the site of Custer's grave, he was reinterred to West Point Cemetery in 1877.

Reno-Benteen Battlefield was added on April 14, 1926. Transferred from the War Department to the National Park Service on July 1, 1940. Redesignated Custer Battlefield National Monument on March 22, 1946. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places on October 15, 1966.[4] The site was renamed Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument by a law signed by President George H. W. Bush on December 10, 1991.

The site was first preserved as a national cemetery in 1879, to protect graves of the 7th Cavalry troopers buried there. It was redesignated Custer Battlefield National Monument in 1946, and later renamed Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument in 1991.

Memorialization on the battlefield began in 1879 with a temporary monument to U.S. dead. This was replaced with the current marble obelisk in 1881. In 1890 the marble blocks that dot the field were added to mark the place where the U.S. cavalry soldiers fell. The bill that changed the name of the national monument also called for an Indian Memorial to be built near Last Stand Hill. On Memorial Day 1999, two red granite markers were added to the battlefield where Native American warriors fell. As of December 2006, there are now a total of ten warrior markers (three at the Reno-Benteen Defense Site, seven on the Custer Battlefield).[5]

The first memorial on the site was assembled by Captain George Sanderson and the 11th Infantry. They buried soldiers' bodies where they were found and removed animal bones. In his official report dated April 7, 1879, Sanderson wrote:

I accordingly built a mound out of cord wood filled in the center with all the horse bones I could find on the field. In the center of the mound I dug a grave and interred all the human bones that could be found, in all, parts of four or five different bodies. This grave was then built up with wood for four feet above ground. The mound is ten feet square and about eleven feet high; is built on the highest point immediately in rear of where Gen’l Custer’s body was found...

Lieutenant Charles F. Roe and the 2nd Cavalry built the granite memorial in July 1881 that stands today on the top of Last Stand Hill. They also reinterred soldiers' remains near the new memorial, but left stakes in the ground to mark where they had fallen. In 1890 these stakes were replaced with marble markers.

The bill that changed the name of the national monument also called for an "Indian Memorial" to be built near Last Stand Hill. It is fairly common at national battle sites in the United States for combatants on both sides of the conflict to be honored. The memorials to U.S. troops have now been supplemented by markers honoring the Indians who fought there, including Crazy Horse. On Memorial Day, 1999, the first of five red granite markers denoting where warriors fell during the battle were placed on the battlefield for Cheyenne warriors Lame White Man and Noisy Walking. The warrior markers dot the ravines and hillsides like the white marble markers representing where soldiers fell. Since then, markers have been added for the Sans Arc Lakota warrior Long Road and the Minniconjou Lakota Dog's Back Bone. On June 25, 2003, an unknown Lakota warrior marker was placed on Wooden Leg Hill, east of Last Stand Hill to honor a warrior who was killed during the battle as witnessed by the Northern Cheyenne warrior Wooden Leg.

Notes

- ↑ US History Encyclopedia. 2006. United States v. Sioux Nation Answers Corporation. Retrieved December 11, 2007.

- ↑ Dee Brown. 1970. Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West. (Owl Books: Henry Holt.), 273

- ↑ John Gray. 1991. Custer's Last Campaign. Lincoln, NE. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0803270402

- ↑ MONTANA - Big Horn County. National Register of Historic Places. Retrieved 2007-04-18.

- ↑ National Park Service website for the Little Bighorn Battlefield

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Print sources

- Donovan, Jim. 2008. A terrible glory: Custer and the Little Bighorn—the last great battle of the American West. New York: Little, Brown and Co. ISBN 9780316155786

- Fox, Richard A. 1993. Archaeology, history, and Custer's last battle: the Little Big Horn reexamined. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 9780806124964

- State of the Parks (Program). 2003. Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument: a resource assessment. Washington, DC: National Parks Conservation Association.

- United States. 1991. An Act, Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument. Washington, D.C.?: U.S. G.P.O.

- United States. 2001. The National parks: index 2001-2003. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Dept. of the Interior.

- Online sources

- Eyewitness to History. The Battle of the Little Bighorn, 1876 Retrieved May 13, 2008.

- Mallery, Garrick. An Eyewitness Account by the Lakota Chief Red Horse, 1881 PBS.org. Retrieved May 13, 2008.

- National Park Service. Indian Memorial At Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument Retrieved May 13, 2008.

- Reece, Bob. Interment of the Custer Dead Friends Of The Little Bighorn Battlefield. Retrieved May 13, 2008.

- Reece, Bob. The Story of the Indian Memorial Friends Of The Little Bighorn Battlefield. Retrieved May 13, 2008.

- US Army Center of Military History. Named Campaigns - Indian Wars Retrieved May 13, 2008.

External links

All links Retrieved May 10, 2008.

- Custer National Cemetery. Crow Agency, Big Horn County, Montana

- Boothill Trip-Custer Battlefield Reenactment

- Curly

- White Man Runs Him

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.