Tourism

Tourism is essentially defined as travel for pleasure, either domestically (within the traveler's own country) or internationally. Tourism is not only an individual or group activity for the enjoyment of the travelers, but has economic implications. The commercial activity of providing and supporting such travel is a significant source of revenue for many locations and enterprises.

Tourism often has significant environmental and social impacts that are not always beneficial to local communities and their economies. For this reason, many tourist development organizations have begun to focus on sustainable tourism to mitigate the negative effects caused by the growing impact of tourism.

Tourism has reached new dimensions with the emerging industry of space tourism, as well as the cruise ship industry. Another potential new tourism industry is virtual tourism.

Etymology

The English-language word tourist was used in 1772[1] and tourism in 1811 to mean "travelling for pleasure."[2] These words derive from the word tour, which comes from Old English turian, from Old French torner, from Latin tornare - "to turn on a lathe," which is itself from Ancient Greek tornos (τόρνος) - "lathe."[3]

Definitions

Tourism is usually considered as travel for pleasure.[2] Tourism typically requires the tourist to feel engaged in a genuine experience of the location they are visiting, such that the tourist can view the toured area as both authentic and different from their own lived experience.[4]

In 1936, the League of Nations defined a foreign tourist as "someone traveling abroad for at least twenty-four hours." Its successor, the United Nations, amended this definition in 1945, by including a maximum stay of six months. This duration of stay has been increased to one year or less by other international organizations.[5]

In 1976, the Tourism Society of England's definition was: "Tourism is the temporary, short-term movement of people to destinations outside the places where they normally live and work and their activities during the stay at each destination."[6]

In 1994, the United Nations identified three forms of tourism in its Recommendations on Tourism Statistics:[7]

- Domestic tourism, involving residents of the given country traveling only within this country

- Inbound tourism, involving non-residents traveling in the given country

- Outbound tourism, involving residents traveling in another country

Other groupings derived from the above grouping:[8]

- National tourism, a combination of domestic and outbound tourism

- Regional tourism, a combination of domestic and inbound tourism

- International tourism, a combination of inbound and outbound tourism

A tourism product is defined as:

a combination of tangible and intangible elements, such as natural, cultural, and man-made resources, attractions, facilities, services and activities around a specific center of interest which represents the core of the destination marketing mix and creates an overall visitor experience including emotional aspects for the potential customers. A tourism product is priced and sold through distribution channels and it has a life-cycle.[9]

History

People have always wanted to travel, either to explore and discover new lands or simply for enjoyment. Tourism, or travel for enjoyment, has a very long history, beginning in ancient times when empires had grown and included many distant lands that excited the interest of those free to travel. In later times it became popular for wealthy young people to spend time on a "Grand Tour" of Europe, an experience that educated them about history, art, and culture. In modern times tourism became an industry, driving the local economies of many attractive locations, with ease of travel and affordability providing the general population with opportunities to experience the excitement of visiting different and distant places.

Ancient

In ancient times, travel outside a person's local area for leisure was largely confined to wealthy classes, who at times traveled to distant parts of the world, to see great buildings and works of art, learn new languages, experience new cultures, enjoy pristine nature, and to taste different cuisines.

As early as the end of the third millennium B.C.E., kings like Shulgi of Ur (reigned from c. 2094 – c. 2046 B.C.E.), praised themselves for protecting roads and building way stations for travelers.[10] Traveling for pleasure can be seen in Egypt as early on as 1500 B.C.E.[11]

Ancient Roman tourists during the Republic would visit spas and coastal resorts such as Baiae. They were popular among the rich. The Roman upper class used to spend their free time on land or at sea and traveled to their villa urbana or villa maritima. Numerous villas were located in Campania, around Rome, and in the northern part of the Adriatic Sea as in Barcola near Trieste. Greek traveler Pausanias wrote his Description of Greece in the second century C.E.[11]

Medieval

By the post-classical era, many religions, including Christianity, Buddhism, and Islam had developed traditions of pilgrimage. The Canterbury Tales (c. 1390s), which uses a pilgrimage as a framing device, remains a classic of English literature, and Journey to the West (c. 1592), which holds a seminal place in Chinese literature, has a Buddhist pilgrimage at the center of its narrative.

In medieval Italy, Petrarch wrote an allegorical account of his 1336 ascent of Mont Ventoux that praised the act of traveling and criticized frigida incuriositas (a 'cold lack of curiosity'); this account is regarded as one of the first known instances of travel being undertaken for its own sake.[12] The Burgundian poet Michault Taillevent later composed his own horrified recollections of a 1430 trip through the Jura Mountains.[13]

In China, "travel record literature" (遊記文學; yóujì wénxué) became popular during the Song Dynasty (960–1279). Travel writers such as Fan Chengda (1126–1193) and Xu Xiake (1587–1641) incorporated a wealth of geographical and topographical information into their writing, while the 'daytrip essay' Record of Stone Bell Mountain by the noted poet and statesman Su Shi (1037–1101) presented a philosophical and moral argument as its central purpose. [14]

Grand Tour

Contemporary tourism can be traced to what was known as the Grand Tour, which was a traditional trip around Europe (especially Germany, France, and Italy), undertaken by upper-class European young men of means maily from Western and Northern European countries.[15] For example in 1624, the young Prince of Poland, Ladislaus Sigismund Vasa, the eldest son of Sigismund III, embarked on a journey across Europe, as was in custom among Polish nobility. It was an educational journey and one of the outcomes was the introduction of Italian opera in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.[16]

The Grand Tour became a status symbol for upper-class students in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. In this period, Johann Joachim Winckelmann's theories about the supremacy of classic culture became very popular and appreciated in the European academic world. Artists, writers, and travelers (such as Goethe) affirmed the supremacy of classic art of which Italy, France, and Greece provide excellent examples. For these reasons, the Grand Tour's main destinations were to those centers, where upper-class students could find rare examples of classic art and history:

Three hundred years ago, wealthy young Englishmen began taking a post-Oxbridge trek through France and Italy in search of art, culture and the roots of Western civilization. With nearly unlimited funds, aristocratic connections and months (or years) to roam, they commissioned paintings, perfected their language skills and mingled with the upper crust of the Continent.[17]

The primary value of the Grand Tour, it was believed, laid in the exposure both to the cultural legacy of classical antiquity and the Renaissance, and to the aristocratic and fashionably polite society of the European continent. The tour generally followed a standard itinerary; it was an educational opportunity and rite of passage. The custom flourished from about 1660 until the advent of large-scale rail transit in the 1840s. Though primarily associated with the British nobility and wealthy landed gentry, similar trips were made by wealthy young men of Protestant Northern European nations on the Continent, and from the second half of the eighteenth century American and other overseas youth joined in. The tradition was extended to include more of the middle class after rail and steamship travel made the journey easier, and Thomas Cook made the "Cook's Tour" a byword.

Emergence of leisure travel

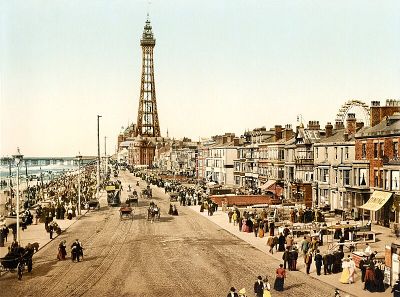

Leisure travel was associated with the Industrial Revolution in the United Kingdom – the first European country to promote leisure time to the increasing industrial population. Initially, this applied to the owners of the machinery of production, the economic oligarchy, factory owners, and traders. These comprised the new middle class.[18] Cox & Kings was the first official travel company to be formed in 1758.[19]

The British origin of this new industry is reflected in many place names. In Nice, France, one of the first and best-established holiday resorts on the French Riviera, the long esplanade along the seafront is known to this day as the Promenade des Anglais; in many other historic resorts in continental Europe, old, well-established palace hotels have names like the Hotel Bristol, Hotel Carlton, or Hotel Majestic – reflecting the dominance of English customers.

A pioneer of the travel agency business, Thomas Cook's idea to offer excursions came to him while waiting for the stagecoach on the London Road at Kibworth. With the opening of the extended Midland Counties Railway, he arranged to take a group of 540 temperance campaigners from Leicester to a rally in Loughborough, 11 miles (18 km) away. On July 5, 1841, Thomas Cook arranged for the rail company to transport the passengers, the first time for most to have traveled by train. It was the first "package holiday" and inspired Cook to do more: “And thus was struck the keynote of my excursions, and the social idea grew upon me.” During the following three summers he planned and conducted outings for temperance societies and Sunday school children, without making any profit. This initial foray into tourism showed that if travel was convenient and accessible, people would travel beyond their familiar locale.[20]

His first commercial venture took place in the summer of 1845, when he organized a trip to Liverpool. He not only provided tickets at low prices, he printed up a brochure detailing the route.

In 1855, having organized trips all over the Britain, he planned his first excursion abroad, taking a group from Leicester to Calais to coincide with the Paris Exhibition. The following year he started his "grand circular tours" of Europe. During the 1860s he took parties to Switzerland, Italy, Egypt, and the United States. Cook established "inclusive independent travel," whereby the traveler went independently but his agency charged for travel, food, and accommodation for a fixed period over any chosen route: a complete holiday “package.” [21]

Economic significance of tourism

The tourism industry, as part of the service sector, has become an important source of income for many regions and even for entire countries.[22] The Manila Declaration on World Tourism of 1980 recognized its importance as "an activity essential to the life of nations because of its direct effects on the social, cultural, educational, and economic sectors of national societies, and on their international relations."[23]

Tourism brings large amounts of income into a local economy in the form of payment for goods and services needed by tourists. It also generates opportunities for employment in the service sector of the economy associated with tourism.

The hospitality industries which benefit from tourism include transportation services (such as airlines, cruise ships, transits, trains, and taxicabs); lodging (including hotels, hostels, homestays, resorts, and renting out rooms); and entertainment venues (such as amusement parks, restaurants, casinos, festivals, shopping malls, music venues, and theatres). This is in addition to goods bought by tourists, including souvenirs.

The economic foundations of tourism are essentially the cultural assets, the cultural property, and the nature of the travel location. The World Heritage Sites are particularly worth mentioning in this context. Also, fascination with the British royal family brings millions of tourists to Great Britain every year and thus boosts the economy. The Habsburg family is a similar attraction in central Europe, particularly Vienna.

Cultural heritage and tourism

Cultural and natural heritage are in many cases the absolute basis for worldwide tourism. Cultural tourism is one of the megatrends that is reflected in massive numbers of overnight stays and sales. As UNESCO is increasingly observing, cultural heritage is needed for tourism, but also endangered by it. The "ICOMOS - International Cultural Tourism Charter" from 1999 is already dealing with all of these problems. As a result of the tourist hazard, for example, the Lascaux cave was rebuilt for tourists.

Modern day tourism

Mass tourism

Mass tourism and its tourist attractions have emerged as among the most iconic demonstration of western consumer societies.[24] This form of tourism developed during the second half of the nineteenth century in the United Kingdom and was pioneered by Thomas Cook. The relationship between tourism companies, transportation operators, and hotels is a central feature of mass tourism. Cook was able to offer prices that were below the publicly advertised price because his company purchased large numbers of tickets from railroads. One contemporary form of mass tourism, package tourism, still incorporates the partnership between these three groups.

Tourist travel developed during the early twentieth century, facilitated by the development of automobiles and later by airplanes. The improvements in transport allowed many people to travel quickly to places of leisure interest, allowing them to enjoy the benefits of leisure time in distant locations.

In Continental Europe, early seaside resorts included: Heiligendamm, founded in 1793 at the Baltic Sea, being the first seaside resort; Ostend, popularized by the people of Brussels; Boulogne-sur-Mer and Deauville for the Parisians; Taormina in Sicily. In the United States, the first seaside resorts in the European style were at Atlantic City, New Jersey and Long Island, New York. By the mid-twentieth century, the Mediterranean Coast became the principal mass tourism destination.

Cruise ships

Cruising is a popular form of tourism. Leisure cruise ships were introduced by the P&O in 1844, sailing from Southampton to destinations such as Gibraltar, Malta, and Athens.[25] In 1891, German businessman Albert Ballin sailed the ship Augusta Victoria from Hamburg into the Mediterranean Sea. June 29, 1900 saw the launching of the first purpose-built cruise ship was Prinzessin Victoria Luise, built in Hamburg for the Hamburg America Line.[26]

Niche tourism

Niche tourism refers to the numerous specialty forms of tourism that have emerged over the years, each with its own adjective. Many of these terms have come into common use by the tourism industry and academics.[27] Others are emerging concepts that may or may not gain popular usage.

Other terms used for niche or specialty travel forms include the term "destination" in the descriptions, such as destination weddings, and terms such as location vacation.

Winter tourism

St. Moritz, Switzerland became the cradle of the developing winter tourism in the 1860s. The story goes that hotel manager Johannes Badrutt invited some summer guests from England to return in the winter to see the snowy landscape, thereby inaugurating a popular trend.[28] It was, however, only in the 1970s when winter tourism took over the lead from summer tourism in many of the Swiss ski resorts.

Recent developments

Tourists have a wide range of budgets and tastes, and a wide variety of resorts and hotels have developed to cater for them. For example, some people prefer simple beach vacations, while others want more specialized holidays, quieter resorts, family-oriented holidays, or niche market-targeted destination hotels.

The developments in air transport infrastructure, such as jumbo jets, low-cost airlines, and more accessible airports have made many types of tourism more affordable. There have also been changes in lifestyle, for example, some retirement-age people sustain year-round tourism. This is facilitated by internet sales of tourist services. Some sites have now started to offer dynamic packaging, in which an inclusive price is quoted for a tailor-made package requested by the customer upon impulse.

Individual low-price or even zero-price overnight stays have become more popular in the 2000s, especially with a strong growth in the hostel market and services like CouchSurfing and airbnb being established.[29]

Sustainable tourism

Sustainable tourism is a concept that covers the complete tourism experience, including concern for economic, social, and environmental issues as well as attention to improving tourists' experiences and addressing the needs of host communities.[30] There is now broad consensus that tourism should be sustainable. In fact, all forms of tourism have the potential to be sustainable if planned, developed and managed properly.[31]

The United Nations tourism organization, UN Tourism, emphasized these practices by promoting tourism as part of the Sustainable Development Goals, through programs like the International Year for Sustainable Tourism for Development in 2017.[32] There is a direct link between sustainable tourism and several of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Tourism for SDGs focuses on how SDG 8 ("decent work and economic growth"), SDG 12 ("responsible consumption and production") and SDG 14 ("life below water") implicate tourism in creating a sustainable economy.[30]

Ecotourism

Ecotourism, also known as ecological tourism, is responsible travel to fragile and relatively pristine natural environments in such a way as to minimize the impact on the environment. It may actually benefit the environment and the local communities, with the latter helping to provide an economic and social incentive to keep these local areas pristine. Take only memories and leave only footprints is a very common slogan in protected areas.[33]

Ecotourism typically involves travel to destinations where flora, fauna, and cultural heritage are the primary attractions. This low-impact, typically small-scale tourism supports conservation through education by offering tourists insight into the impact of human beings on the environment and fostering a greater appreciation of natural habitats. By improving the well-being of the local people, the communities have a vested interest in keeping the natural areas attractive to tourists. Ecotourism may also benefit the environment through direct financial contributions toward conservation. Thus, ecotourism helps educate the traveler; provides funds for conservation; directly benefits the economic development and political empowerment of local communities, and fosters respect for different cultures and for human rights.

Volunteer tourism

Volunteer tourism (or voluntourism) is growing as a largely Western phenomenon, with volunteers traveling to aid those less fortunate than themselves in order to counter global inequalities. Volunteer tourism may be applied "to those tourists who, for various reasons, volunteer in an organized way to undertake holidays that might involve aiding or alleviating the material poverty of some groups in society."[34]

This form of tourism is largely praised for its more sustainable approach to travel, with tourists attempting to assimilate into local cultures, and avoiding the criticisms of consumptive and exploitative mass tourism.Cite error: Closing </ref> missing for <ref> tag while host communities without a strong heritage fail to retain volunteers who become dissatisfied with experiences and volunteer shortages persist.[35]

Recession tourism or Staycation

Recession tourism is a travel trend which evolved by way of the world economic slowdown and recession. Recession tourism is defined by low-cost and high-value experiences taking place at once-popular generic retreats. Various recession tourism hotspots have seen business boom during the recession thanks to comparatively low costs of living and a slow world job market suggesting travelers are elongating trips where their money travels further.

This type of tourism is related to the phenomenon that is more widely known as staycation (a portmanteau of "stay" and "vacation"). This is a period of time in which an individual or family stays home and participates in leisure activities within day trip distance of their home and does not require overnight accommodation.

Educational tourism

Template:More citations needed section Educational tourism is developed because of the growing popularity of teaching and learning of knowledge and the enhancing of technical competency outside of the classroom environment. Brent W. Ritchie, publisher of Managing Educational Tourism, created a study of a geographic subdivision to demonstrate how tourism educated high school students participating in foreign exchange programs over the last 15 years.[36] In educational tourism, the main focus of the tour or leisure activity includes visiting another country to learn about the culture, study tours, or to work and apply skills learned inside the classroom in a different environment, such as in the International Practicum Training Program.[37] In 2018, one impact was many exchange students traveled to America to assist students financially in order to maintain their secondary education.[38]

Event tourism

This type of tourism is focused on tourists coming into a region to either participate in an event or to see an organized event put on by the city/region.[39] This type of tourism can also fall under sustainable tourism as well and companies that create a sustainable event to attend open up a chance to not only the consumer but their workers to learn and develop from the experience. Creating a sustainable atmosphere creates a chance to inform and encourage sustainable practices. An example of event tourism would be the music festival South by Southwest that is hosted in Austin, Texas annually. Every year people from all over the world flock to the city for one week to sit in on technology talks and see bands perform. People are drawn here to experience something that they are not able to experience in their hometown, which defines event tourism.

Creative tourism

Creative tourism has existed as a form of cultural tourism, since the early beginnings of tourism itself. Its European roots date back to the time of the Grand Tour, which saw the sons of aristocratic families travelling for the purpose of mostly interactive, educational experiences. More recently, creative tourism has been given its own name by Crispin Raymond and Greg Richards,[40] who as members of the Association for Tourism and Leisure Education (ATLAS), have directed a number of projects for the European Commission, including cultural and crafts tourism, known as sustainable tourism. They have defined "creative tourism" as tourism related to the active participation of travellers in the culture of the host community, through interactive workshops and informal learning experiences.[40]

Meanwhile, the concept of creative tourism has been picked up by high-profile organizations such as UNESCO, who through the Creative Cities Network, have endorsed creative tourism as an engaged, authentic experience that promotes an active understanding of the specific cultural features of a place. UNESCO wrote in one of its documents: "'Creative Tourism' involves more interaction, in which the visitor has an educational, emotional, social, and participative interaction with the place, its living culture, and the people who live there. They feel like a citizen."[41] Saying so, the tourist will have the opportunity to take part in workshops, classes and activities related to the culture of the destination.

More recently, creative tourism has gained popularity as a form of cultural tourism, drawing on active participation by travellers in the culture of the host communities they visit. Several countries offer examples of this type of tourism development, including the United Kingdom, Austria, France, the Bahamas, Jamaica, Spain, Italy, New Zealand and South Korea.[42][43]

The growing interest of tourists[44] in this new way to discover a culture regards particularly the operators and branding managers, attentive to the possibility of attracting a quality tourism, highlighting the intangible heritage (craft workshops, cooking classes, etc.) and optimizing the use of existing infrastructure (for example, through the rent of halls and auditoriums).

Dark tourism

One emerging area of special interest has been identified by Lennon and Foley (2000)[45][46] as "dark" tourism. This type of tourism involves visits to "dark" sites, such as battlegrounds, scenes of horrific crimes or acts of genocide, for example concentration camps. Its origins are rooted in fairgrounds and medieval fairs.[47]

Philip Stone argues that dark tourism is a way of imagining one's own death through the real death of others.[48] Erik H Cohen introduces the term "populo sites" to evidence the educational character of dark tourism. Popular sites transmit the story of victimized people to visitors. Based on a study at Yad Vashem, the Shoah (Holocaust) memorial museum in Jerusalem, a new term—in populo—is proposed to describe dark tourism sites at a spiritual and population center of the people to whom a tragedy befell. Learning about the Shoah in Jerusalem offers an encounter with the subject which is different from visits to sites in Europe, but equally authentic. It is argued that a dichotomy between "authentic" sites at the location of a tragedy and "created" sites elsewhere is insufficient. Participants' evaluations of seminars for European teachers at Yad Vashem indicate that the location is an important aspect of a meaningful encounter with the subject. Implications for other cases of dark tourism at in populo locations are discussed.[49] In this vein, Peter Tarlow defines dark tourism as the tendency to visit the scenes of tragedies or historically noteworthy deaths, which continue to impact our lives. This issue cannot be understood without the figure of trauma.[50]

Victoria Mitchell et al. suggest that dark tourism seems to be a heterogeneous discipline. There is a great dispersion of definitions, knowledge production and meanings revolving around the term. In fact, dark tourism practices vary in culture and time. Qualitative speaking, dark tourism experience is pretty different from leisure practices. To fill the gap, the existent definitions should be catalogued in sub-categories to form an all-encompassing model that expands the current understanding of dark tourism.[51] In consonance with this, M. Apleni et al. argue dark tourism helps the industry not to be fragmented before the ongoing states of crises the activity often faces. They cite the case of terrorism which paves the way for the construction of a new dark site. Dark tourism plays a leading role not only in enhancing destination resilience but also in helping communities to deal with traumatic experiences.[52]

Last chance tourism

"Last chance tourism," also known as "tourism of doom," involves traveling to places that are environmentally or otherwise threatened (such as the ice caps of Mount Kilimanjaro, the melting glaciers of Patagonia, or the coral of the Great Barrier Reef) before it is too late. Identified by travel trade magazine Travel Age West[53] editor-in-chief Kenneth Shapiro in 2007 and later explored in The New York Times,[54] this type of tourism is believed to be on the rise. Some see the trend as related to sustainable tourism or ecotourism due to the fact that a number of these tourist destinations are considered threatened by environmental factors such as global warming, overpopulation or climate change. Others worry that travel to many of these threatened locations increases an individual's carbon footprint and only hastens problems threatened locations are already facing.[55][56][57][58][59]

Religious tourism

Religious tourism, in particular pilgrimage, can serve to strengthen faith and to demonstrate devotion.[60] Religious tourists may seek destinations whose image encourages them to believe that they can strengthen the religious elements of their self-identity in a positive manner. Given this, the perceived image of a destination may be positively influenced by whether it conforms to the requirements of their religious self-identity or not.[61]

Space tourism

There has been a limited amount of orbital space tourism, with only the Russian Space Agency providing transport to date. A 2010 report into space tourism anticipated that it could become a billion-dollar market by 2030.[62][63] The space market has been around since 1979, however, there has been a limited amount of orbital space tourism, with only the Russian Space Agency providing transport on its Soyuz and the Chinese Shenzhou being the only two spacecrafts suitable for human travel . In April 2001, Dennis Tito, a customer of the Russian Soyuz became the first tourist to visit space. In May 2011, Virgin Galactic launched its SpaceShipTwo plane that allows people to travel 2 hours space at the advertised price of $200,000 per seat. A challenge that the commercial space tourism industry faces is to be able to have fundings from private investments needed to lower the cost of access to space in addition to being able to encourage both private and public sector support to increase capacity to allow commercial passengers. With space tourism still being new concept, there are many factors that needs to be considered for the industry. From its actual demand to its risk factor to its liabilities and insurance issues, there are still a lot of research that needs to be conducted. A 2010 report into space tourism anticipated that the industry is expected to grow by 18% - 26% per year during 2020 to 2030.

DNA tourism

DNA tourism, also called "ancestry tourism" or "heritage travel," is tourism based on DNA testing. These tourists visit their remote relatives or places where their ancestors came from, or where their relatives reside, based on the results of DNA tests. DNA tourism became a growing trend in 2019.[64]

Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic

Tourism numbers had declined as a result of a strong economic slowdown (the late-2000s recession) between the second half of 2008 and the end of 2009, and in consequence of the outbreak of the 2009 H1N1 influenza virus, but were slowly recovering until the COVID-19 pandemic put an abrupt end to the growth.

In 2020 the COVID-19 pandemic travel bans and a substantial reduction in passenger travel by air and sea contributed to a sharp decline in tourism activity.[65] Nearly all sectors within the tourism industry were significantly impacted by the pandemic. Airlines had large losses of revenue due to reduced number of passengers. In the food industry, many restaurants had to close which caused a ripple-effect to its related industries such as food production, farming, shipping, etc. As for the hotel industry, by June 2020 most of the hotels rooms were empty throughout the United States of America.

Virtual tourism is an emerging market that was popularized as an alternative solutions to in person tourism during the pandemic. Since many places like museums want to restrict crowdedness, virtual tours are set up to provide visitors the experience without posing any health risks. This created new business models and provide new and inventive opportunities for the tourism industry. However, virtual tourism cannot provide the same experience for people compared to in person visits.

Notes

- ↑ Ralph Griffiths, Pennant's Tour in Scotland in 1769 The Monthly Review, Or, Literary Journal 46 (1772): 150. Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Douglas Harper, tourism (n.) Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ↑ Douglas Harper, turn (v.) Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ↑ Dean Maccannell, The Tourist: A New Theory of the Leisure Class (University of California Press, 2013, ISBN 978-0520280007).

- ↑ William F. Theobald (ed.),Global Tourism (Routledge, 2004, ISBN 978-0750677899).

- ↑ Allan Beaver, A Dictionary of Travel and Tourism Terminology (Oxford University Press, 2006, ISBN 978-0851990200).

- ↑ United Nations and World Tourism Organization, Recommendations on Tourism Statistics Statistical Papers Series M No. 83, 1994. Retrieved June 24, 2024.

- ↑ Glossary:Tourism - Statistics Explained Eurostat Statistics Explained. Retrieved June 24, 2024.

- ↑ Product Development UN Tourism. Retrieved June 24, 2024.

- ↑ N. Jayapalan, An Introduction To Tourism (Atlantic Publishers, 2013, ISBN 978-8171569779).

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Lionel Casson, Travel in the Ancient World (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1994, ISBN 978-0801848087).

- ↑ Petrarch, The Ascent of Mount Ventoux Medieval Sourcebook. Retrieved June 24, 2024.

- ↑ Robert Deschaux, Un poète bourguignon du XVe siècle, Michault Taillevent (Librairie Droz, 1975, ISBN 978-2600028318).

- ↑ James M. Hargett, Some Preliminary Remarks on the Travel Records of the Song Dynasty (960-1279) Chinese Literature: Essays, Articles, Reviews 7(1/2) (July 1985): 67–93. Retrieved June 24, 2024.

- ↑ Carmen Périz Rodríguez, Travelling for pleasure: a brief history of tourism Europeana, June 16, 2020. Retrieved June 25, 2024.

- ↑ Polish National Opera and Ballet Opera Vision. Retrieved June 25, 2024.

- ↑ Matt Gross, Lessons From the Frugal Grand Tour The New York Times (September 5, 2008). Retrieved June 24, 2024.

- ↑ L.K. Singh, Fundamental Of Tourism & Travel (Isha Books, 2008, ISBN 978-8182054783).

- ↑ About Us Cox & Kings. Retrieved June 25, 2024.

- ↑ Thomas Cook's History Thomas Cook. Retrieved June 25, 2024.

- ↑ Thomas Cook History (archive) Thomas Cook. Retrieved June 24, 2024.

- ↑ Dimitri Tassiopoulos (ed.), New Tourism Ventures: An Entrepreneurial and Managerial Approach (Juta Publishers, 2008, ISBN 978-0702177262).

- ↑ Manila Declaration on World Tourism The World Tourism Conference, Manila, Philippines, September 27 to October 10, 1980. Retrieved June 25, 2024.

- ↑ Pau Obrador Pons, Mike Crang, and Penny Travlou (eds.), Cultures of Mass Tourism: Doing the Mediterranean in the Age of Banal Mobilities (Routledge, 2009, ISBN 978-0754672135).

- ↑ A Short History of P&O BTNews (June 25, 2012). Retrieved June 25, 2024.

- ↑ Michael Grace, The Prinzessin Victoria Luise – world’s first cruise ship Cruise The Past, July 13, 2009. Retrieved June 25, 2024.

- ↑ Alan A. Lew, Long Tail Tourism: New geographies for marketing niche tourism products Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 25(3): (December 2008): 409-419. Retrieved June 25, 2024.

- ↑ Mary Novakovich, The birth of winter tourism in St Moritz Financial Times (October 24, 2014). Retrieved June 25, 2024.

- ↑ Patricia Marx, You’re Welcome The New Yorker (April 9, 2012). Retrieved June 25, 2024.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Sustainable development UN Tourism. Retrieved June 25, 2024.

- ↑ David A. Fennell and Chris Cooper, Sustainable Tourism: Principles, Contexts and Practices (Channel View Publications, 2020, ISBN 978-1845417666).

- ↑ Tourism and the Sustainable Development Goals – Journey to 2030, Highlights UN Tourism Publications, December 2017. Retrieved June 25, 2024.

- ↑ History of the Leave Only Footprints Initiative Leave Only Footprints. Retrieved June 26, 2024.

- ↑ Stephen Wearing, Volunteer Tourism: Experiences That Make a Difference (CABI, 2001, ISBN 0851995330).

- ↑ Ross Curran, Babak Taheri, Robert MacIntosh, and Kevin O’Gorman, Nonprofit Brand Heritage: Its Ability to Influence Volunteer Retention, Engagement, and Satisfaction Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 45(6) (July 9, 2016): 1234-1257. Retrieved June 26, 2024.

- ↑ (2017-01-01)Rethinking educational tourism: proposing a new model and future directions. Tourism Review 72 (3): 319–329.

- ↑ Seraphin, H., Bah, M., Fyall, A., & Gowreesunkar, V. (2021). Tourism education in France and sustainable development goal 4 (quality education). Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes.

- ↑ Shulman, Robyn D.. 5 Ways Student Exchange Programs Affect The American Economy (in en).

- ↑ Clare., Inkson (2012). Tourism management : an introduction, Minnaert, Lynn, Los Angeles: Sage. ISBN 978-1-84860-869-6. OCLC 760291882.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Wurzburger, Rebecca (2009). Creative Tourism: A Global Conversation: How to Provide Unique Creative Experiences for Travelers Worldwide: As Presented at the 2008 Santa Fe & UNESCO International Conference on Creative Tourism in Santa Fe, New Mexico, USA. Santa Fe: Sunstone Press. ISBN 978-0-86534-724-3. OCLC 370387178.

- ↑ "Towards Sustainable Strategies for Creative Tourism: discussion report of the planning meeting for the 2008 International Conference on Creative Tourism", UNESCO Digital Library, 2006.

- ↑ Lau, Samantha (14 November 2016). Creative tourism.

- ↑ Creative Friendly Destinations.

- ↑ Charlie Mansfield Lecturer in Tourism Management and French. JTCaP Tourism Consumption Online Journal. Tourismconsumption.org.

- ↑ Quinion, Michael (26 November 2005). Dark Tourism. World Wide Words.

- ↑ (2000) Dark Tourism. London: Continuum. ISBN 978-0-8264-5063-0. OCLC 44603703.

- ↑ Cooper, Chris (2005). Tourism: Principles and Practice, 3rd, Harlow: Pearson Education. ISBN 978-0-273-68406-0. OCLC 466952897.

- ↑ Stone, Philip R. (1 July 2012). Dark tourism and significant other death: Towards a Model of Mortality Mediation. Annals of Tourism Research 39 (3): 1565–87.

- ↑ Cohen, Erik H. (1 January 2011). Educational dark tourism at an in populo site: The Holocaust Museum in Jerusalem. Annals of Tourism Research 38 (1): 193–209.

- ↑ Novelli, Marina (2007). Niche Tourism (in en). Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-37617-7.

- ↑ Mitchell, V., Henthorne, T. L., & George, B. (2020). Making Sense of Dark Tourism: Typologies, Motivations and Future Development of Theory. In Tourism, Terrorism and Security. Bingley, Emerald Publishing Limited.

- ↑ Apleni, L., Mangwane, J., Maphanga, P. M., & Henama, U. S. (2020). The Interface between Dark Tourism and Terrorism in Africa: The Case of Kenya and St Helena. In Tourism, Terrorism and Security. Bingley, Emerald Publishing Limited.

- ↑ Shapiro, Kenneth (11 May 2007). The Tourism of Doom. TravelAge West.

- ↑ Salkin, Allen, "'Tourism of doom' on rise", The New York Times, 16 December 2007.

- ↑ Lemelin, H., Dawson, J., & Stewart, E.J. (Eds.). (2013). Last chance tourism: adapting tourism opportunities in a changing world. Routledge.

- ↑ Frew, E. (2008). Climate change and doom tourism: Advertising destinations 'before they disappear'. In J. Fountain & K. Moore (Chair), Symposium conducted at the meeting of the New Zealand Tourism & Hospitality Research Conference.

- ↑ Tsiokos, C. (2007). Doom tourism: While supplies last. Population Statistics.

- ↑ Hall, C.M. (2010). Crisis events in tourism: subjects of crisis in tourism. Current Issues in Tourism, 13(5), 401–17.

- ↑ Olsen, D.H., Koster, R.L., & Youroukos, N. (2013). 8 Last chance tourism?. Last Chance Tourism: Adapting Tourism Opportunities in a Changing World, 105.

- ↑ (1 January 2014)Muslim world and its tourisms. Annals of Tourism Research 44: 1–19.

- ↑ Compare: (11 June 2017)Travelling for Umrah: destination attributes, destination image, and post-travel intentions. The Service Industries Journal 37 (7–8): 448–65.

- ↑ The Economic Impact of Commercial Space Transportation on the U. S Economy in 2009. Federal Aviation Administration (September 2010).

- ↑ Cohen, E. (2017). The paradoxes of space tourism. Tourism Recreation Research, 42(1), 22-31.

- ↑ Dana McMahan, Why DNA tourism may be the big travel trend of 2019 NBC News (December 9, 2018). Retrieved June 25, 2024.

- ↑ Curtis Tate, International tourism won't come back until late 2021, UN panel predicts USA Today (October 28, 2020). Retrieved June 25, 2024.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Beaver, Allan. A Dictionary of Travel and Tourism Terminology. Oxford University Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0851990200

- Casson, Lionel. Travel in the Ancient World. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1994. ISBN 978-0801848087

- Deschaux, Robert. Un poète bourguignon du XVe siècle, Michault Taillevent. Librairie Droz, 1975. ISBN 978-2600028318

- Fennell, David A., and Chris Cooper. Sustainable Tourism: Principles, Contexts and Practices. Channel View Publications, 2020. ISBN 978-1845417666

- Jayapalan, N. An Introduction To Tourism. Atlantic Publishers, 2013. ISBN 978-8171569779

- Maccannell, Dean. The Tourist: A New Theory of the Leisure Class. University of California Press, 2013. ISBN 978-0520280007

- Pons, Pau Obrador, Mike Crang, and Penny Travlou (eds.). Cultures of Mass Tourism: Doing the Mediterranean in the Age of Banal Mobilities. Routledge, 2009. ISBN 978-0754672135

- Singh, L.K. Fundamental Of Tourism & Travel. Isha Books, 2008. ISBN 978-8182054783

- Tassiopoulos Dimitri (ed.). New Tourism Ventures: An Entrepreneurial and Managerial Approach. Juta Publishers, 2008. ISBN 978-0702177262

- Theobald, William F. (ed.). Global Tourism. Routledge, 2004. ISBN 978-0750677899

- Wearing, Stephen. Volunteer Tourism: Experiences That Make a Difference. CABI, 2001. ISBN 0851995330

External links

All links retrieved June 20, 2024.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.