| Aleut | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Traditional Aleut dress | ||||||

| Total population | ||||||

| 17,000 to 18,000 | ||||||

| Regions with significant populations | ||||||

| ||||||

| Languages | ||||||

| English, Russian, Aleut | ||||||

| Religions | ||||||

| Christianity, Shamanism | ||||||

| Related ethnic groups | ||||||

| Inuit, Yupiks |

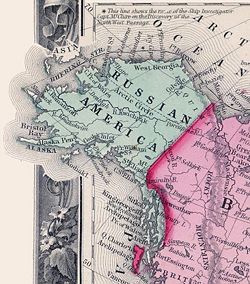

The Aleuts (Unangax, Unangan or Unanga) are the indigenous people of the Aleutian Islands of Alaska, United States and Kamchatka Oblast, Russia. They are related to the Inuit and Yupik people. The homeland of the Aleuts includes the Aleutian Islands, the Pribilof Islands, the Shumagin Islands, and the far western part of the Alaskan Peninsula.

They were skilled at hunting and fishing in this harsh climate, skills that were exploited by Russian fur traders after their arrival around 1750. They received assistance and support from the Russian Orthodox missionaries subsequently and became closely aligned with Orthodox practices and beliefs. Despite this, an estimated 90 percent of the population died during the years of Russian fur trade. The tribe has nonetheless made a recovery, and their wisdom and perseverance are qualities that allow them to work with others in the process of building a world of peace.

Name

The Aleut (pronounced al-ee-oot) people were so named by Russian fur traders during the Russian fur trade period in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Their original name was Unangan, meaning "coastal people.‚ÄĚ

History

The Aleut trace permanent settlement to about 8,000 years ago in the Aleutian archipelago that stretches over 1,300 miles between Alaska and Siberia. Anthropologists are not certain of their exact origins (Siberia or Subarctic) but most believe they arrived later than the more southern tribes (around 4,000 years ago). Two cultures developed: the Kodiak (circa 2,500 B.C.E.) and Aleutian (circa 2,000 B.C.E.).[1]

The Aleuts' skill at hunting and surviving in the hard environment made them valuable and later exploited by Russian fur traders after their arrival in 1750.[2] Russian Orthodox missionaries referred to the austere environment as ‚Äúthe place that God forgot.‚ÄĚ [3]

Within fifty years after Russian contact, the population of the Aleut was 12,000 to 15,000 people. At the end of the twentieth century, it was 2,000.[4] Eighty percent of the Aleut population had died through violence and European diseases, against which they had no defense. There was, however, a counterbalancing force that came from the missionary work of the Russian Orthodox Church. The priests, who were educated men, took great interest in preserving the language and lifestyle of the indigenous people of Alaska. One of the earliest Christian martyrs in North America was Saint Peter the Aleut.

Fur trade first annihilated the sea otter and then focused on the massive exploitation of fur seals. Aleutian men were transported to areas where they were needed on a seasonal basis. The Pribilof Islands (named for Russian navigator Gavriil Pribilof’s discovery in 1786) became the primary place where seals were harvested en masse. The Aleuts faired well during this period as Russian citizens but rapidly lost status after the American purchase of Alaska in 1867. Aleuts lost their rights and endured injustices.

In 1942, Japanese forces occupied Attu and Kiska Islands in the western Aleutians, and later transported captive Attu Islanders to HokkaidŇć, where they were held as POWs. Hundreds more Aleuts from the western chain and the Pribilofs were evacuated by the United States government during World War II and placed in internment camps in southeast Alaska, where many died.

It was not until the mid-1960s that the Aleuts were given American citizenship. In 1983, the U.S. government eliminated all financial allocations to the inhabitants of the Pribilofs. A trust fund of 20 million dollars was approved by Congress to initiate alternative sources of income such as fishing. This proved very successful as the Pribilofs became a primary point for international fishing vessels and processing plants. The Aleut Restitution Act of 1988 was an attempt by Congress to compensate survivors of the internment camps. By the late 1990s, the impact of environmental changes began to cast shadows over the economy of the North Sea region.

Culture

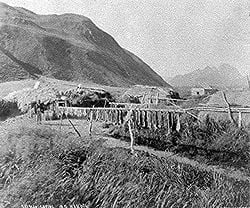

Aleut settlements were located by the coast, usually on bays with fresh water nearby to ensure a good salmon stream. They also chose locations with an elevated lookout and an escape route in case of attack by enemies.[5]

Aleuts constructed "barabaras" (or ulax), partially underground houses which protected them from the harsh climate. The roof of a barabara was generally made from sod layered over a frame of wood or whalebone, and contained a roof doorway for entry. The entrance typically had a little wind envelope or "Arctic entry" to prevent cold wind, rain or snow from blowing into the main room and cooling it off. There was usually a small hole in the ceiling from which the smoke from the fire escaped.[6]

Fishing and hunting and gathering provided the Aleuts with food. Salmon, seal, walrus, whale, crabs, shellfish, and cod were all caught and dried, smoked or roasted. Caribou, deer, moose, and other types of game were eaten roasted or preserved. Berries were dried or made into alutiqqutigaq, a mixture of berries, fat, and fish. The Aleut used skin covered kayaks (or iqyax) to hunt marine mammals.[7] They used locally available materials, such as driftwood and stone, to make tools and weapons.[5]

Language

The Aleut language is in the Eskimo-Aleut languages family. It is divided at Atka Island into the Eastern and the Western dialects.[7] Their language is related to the Inuit and Yupik languages spoken by the Eskimo. It has no known wider affiliation, but supporters of the Nostratic hypothesis sometimes include it as Nostratic.

Ivan Veniaminov began to develop a writing system in 1824 for the Aleut language so that educational and religious materials could be translated. Continuous work has taken place through the work of dedicated linguists through the twentieth century. Knut Bergsland from 1950 until his death in 1998 worked with Aleut speakers and produced a comprehensive Aleut dictionary in 1994, and in 1997 a detailed reference grammar book.[7]

Social structure

Prior to Russian contact, Aleut society was a ranked system of heredity classes. There were positions similar to nobles, commoners, and slaves in the Western world. The highest ranking were given special places in the long house as well as burial sites. The east was important as the place where the Creator, Agugux, resided, thus the best place to be located.[5]

Religion

Aleut men honored creatures of the sea and honored them through the ornamentation on their hunting costumes. Hunting was the lifeline of the Aleut people. Animals, fish, and birds were revered and considered to have souls. Rituals were sometimes performed to release the hunted animal's soul. Newborn babies were named after someone who had died in order that the deceased person could live on in the child. There was also a belief in the soul going to a land in the sea or sky. Wooden masks of animals were often used in ritual dances and story telling.

Shamans were very important. They were able to go into a trance and receive messages from spirits to help with the hunting or with healing. They also could perform evil actions against others. Important deities were Sea Woman (Sedna) in charge of sea animals, Aningaaq in charge of the sun, and Sila in charge of the air.

Clothing

The Aleut people live in one of the harshest parts of the world. Both men and women wore parkas (Kamleika) the come down below the knees to provide adequate protection. The women's parkas were made of skin of seal or sea-otter skin and the men wore bird skin parkas that had the feathers inside and out depending on the weather. When the men were hunting on the water they wore waterproof hooded parkas made from seal or sea-lion guts, or the entrails of bear, walrus, and whales. Children wore parkas made of downy eagle skin with tanned bird skin caps.[8]

One parka took a year to make and would last two years with proper care. All parkas were decorated with bird feathers, beard bristles of seal and sea-lion, beaks of sea parrots, bird claws, sea otter fur, dyed leather, and caribou hair sewn in the seams. Colored threads made of sinews of different animals and fish guts were also used for decoration.[8] The threads were dyed different colors using vermilion paint, hematite, the ink bag of the octopus, and the roots of grasses.[9]

Arts

Weapon-making, building of baidarkas (special hunting boats), and weaving are some of the traditional arts of the Aleuts. Nineteenth-century craftsmen were famed for their ornate wooden hunting hats, which feature elaborate and colorful designs and may be trimmed with sea lion whiskers, feathers, and ivory. Aleut seamstresses created finely stitched waterproof parkas from seal gut, and some women still master the skill of weaving fine baskets from rye and beach grass. Aleut men wore wooden hunting hats. The length of the visor indicated rank.

Aleut carvings are distinct in each region and have attracted traders for centuries. Most commonly the carvings of ivory and wood were for the purpose of hunting weapons. Other times the carvings were created to depict commonly seen animals, such as seals, whales, and even people.[10]

The Aleuts also use ivory in jewelry and custom made sewing needles often with a detailed end of carved animal heads. Jewelry is worn as lip piercings, nose piercings, necklaces, ear piercings, and piercings through the flesh under the bottom lip.[10]

Aleut basketry is some of the finest in the world, the continuum of a craft dating back to prehistoric times and carried through to the present. Early Aleut women created baskets and woven mats of exceptional technical quality using only an elongated and sharpened thumbnail as tool. Today Aleut weavers continue to produce woven pieces of a remarkable cloth-like texture, works of modern art with roots in ancient tradition. The Aleut word for grass basket is qiigam aygaaxsii.

Masks are full of meaning in the Aleut culture. They may represent creatures described in Aleut language, translated by Knut Bergsland as ‚Äúlike those found in caves.‚ÄĚ Masks were generally carved from wood and were decorated with paints made from berries or other earthly products. Feathers were also inserted into holes carved out for extra decoration. These masks were used from ceremonies to dances to praises, each with its own meaning and purpose.[10]

Contemporary Issues

Following a devastating oil spill in 1996, the Aleut could not deny that life was again changing for them and future generations. A revival of interest in Aleut culture has subsequently been initiated. Leaders have worked to help the Aleut youth understand their historic relationship with the environment and to seek opportunities to work on behalf of the environment for the future. In 1998, Aleut leader, Aquilina Bourdukofsky wrote: ‚ÄúI believe we exist generationally. Would we be as strong as we are if we didn‚Äôt go through the hardships, the slavery? It‚Äôs powerful to hear the strength of our people ‚Äď that‚Äôs what held them together in the past and today.‚ÄĚ[2]

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ Barry Pritzker, A Native American Encyclopedia (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2000, ISBN 0195138775).

- ‚ÜĎ 2.0 2.1 Helen D. Corbett and Susanne M. Swibold, The Aleuts of the Pribilof Islands, Alaska Retrieved November 3, 2011. Reproduced with permission from Milton M.R. Freeman (ed.), Endangered people of the Arctic: Struggles to Survive and Thrive (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2000, ISBN 978-0313306495).

- ‚ÜĎ Michael Oleksa, Alaskan Missionary Spirituality, (New York, NY: Paulist Press, 1987, ISBN 0809103869).

- ‚ÜĎ Margaret Lantis, Handbook of North American Indians Volume 5 Arctic David Damas (ed.) (Washington DC: Smithsonian Institute Press, 1984, ISBN 0874741858), 163.

- ‚ÜĎ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Lydia T. Black and R. G. Liapunova, Aleut Arctic Studies Center. Retrieved November 3, 2011.

- ‚ÜĎ Peter Nabokov and Robert Easton, Native American Architecture. (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1989, ISBN 0195037812), 205.

- ‚ÜĎ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Aleutian Pribilof Island Community Development Association, Aleut Culture Retrieved November 3, 2011.

- ‚ÜĎ 8.0 8.1 J. Joseph Gross and Sigrid Khera, Ethnohistory of the Aleuts (Fairbanks, AK: University of Alaska, 1980), 33-34.

- ‚ÜĎ Lucien Turner, An Aleutian Ethnography Raymond L. Hudson (ed.) (Fairbanks, AK: University of Alaska Press, 2010, ISBN 978-1602230392), 71.

- ‚ÜĎ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Lydia Black, Aleut Art Unangam Aguqaadangin (Anchorage, AK: Aleutian/Pribilof Islands Association, 2003, ISBN 978-1578642144).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bergsland, Knut. Aleut Dictionary: Unangam Tundguaii. Fairbanks, AK: Alaska Native Language Center, 1994. ISBN 978-1555000479

- Bergsland, Knut. Aleut Grammar: Unangam Tunuganaan Achixaasix. Fairbanks, AK: Alaska Native Language Center, 1997. ISBN 978-1555000646

- Black, Lydia. Aleut Art Unangam Aguqaadangin. Anchorage, AK: Aleutian/Pribilof Islands Association, 2003. ISBN 978-1578642144

- Damas, David (ed.). Handbook of North American Indians Volume 5 Arctic. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institute Press, 1984. ISBN 0874741858

- Freeman, Milton M.R. (ed.). Endangered people of the Arctic: Struggles to Survive and Thrive. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0313306495

- Lantis, Margaret. Ethnohistory in Southwestern Alaska and the Southern Yukon. Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky Press, 1970. ISBN 081311215X

- Nabokov, Peter, and Robert Easton. Native American Architecture. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1989. ISBN 0195037812

- Oleksa, Michael. Alaskan Missionary Spirituality. New York, NY: Paulist Press. 1987. ISBN 0809103869

- Pritzker, Barry. A Native American Encyclopedia New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2000. ISBN 0195138775

- Turner, Lucien. An Aleutian Ethnography Raymond L. Hudson (ed.). Fairbanks, AK: University of Alaska Press, 2010. ISBN 978-1602230392

External links

All links retrieved June 17, 2023.

- The AMIQ Institute - a research project documenting the Pribilof Islands and their inhabitants.

- The Aleut Foundation

- Aleutian Pribilof Islands Association

- Museum of the Aleutians

- Aleutian Pribilof Island Community Development Association

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.