| Frog

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

White's Tree Frog (Litoria caerulea)

| ||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||

| ||||||||

Distribution of frogs (in black)

| ||||||||

|

Archaeobatrachia |

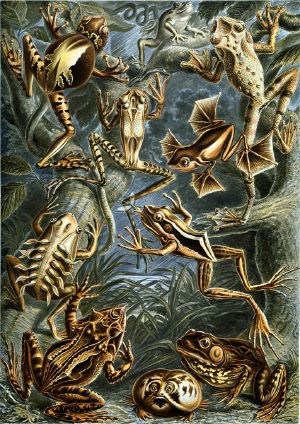

Frog is the common name for any of the members of the amphibian order Anura, whose extant species are characterized by an adult with longer hind legs among the four legs, a short body, webbed digits, protruding eyes, and the absence of a tail. Anura means "tail-less," coming from the Greek an-, meaning "without," and oura, meaning "tail." Formerly, this order was referred to as Salientia, from the Latin saltare, meaning "to jump." Anurans have well-developed voices, whereas the other two orders of amphibians are limited to sounds such as coughs and grunts.

Frogs are the most numerous and diverse amphibians, being found in nearly all habitats, including arboreal, aquatic, and terrestrial niches, and every continent except Antarctica. Three species have ranges that extend above the Arctic Circle. The greatest diversity is in tropical rainforests. Overall, about 88 percent of amphibian species are frogs, with the order Anura containing 5,250 species in 33 families, of which the Leptodactylidae (1100 spp.), Hylidae (800 spp.) and Ranidae (750 spp.) are the richest in species.

A distinction is often made between frogs and toads on the basis of their appearance, with toad the common term imprecisely applied to largely terrestrial members of Anura that are characterized by short legs, a stocky body, and a drier, warty or bumpy skin and frogs those members that are aquatic or semi-aquatic with slender bodies, longer legs, and smooth and/or moist skins.

However, this division of anurans into toads and frogs is a popular, not a scientific distinction; it does not represent a formal taxonomic rank. From a taxonomic perspective, all members of the order Anura are frogs. The only family exclusively given the common name "toad" is Bufonidae, the "true toads," although many species from other families are also called toads. The anuran family "Ranidae" is known as the "true frogs."

Most anurans have a semi-aquatic lifestyle, but move easily on land by jumping or climbing. They typically lay their eggs in puddles, ponds, or lakes, and their larvae, called tadpoles, have gills and develop in water. Though adults of some species eat plants, adult frogs of almost all species follow a carnivorous diet, mostly of arthropods, annelids, and gastropods. Some tadpoles are carnivorous as well. Frogs are most noticeable by their call, which can be widely heard during the night or day, mainly in their mating season.

Frogs provide many ecological, commercial, scientific, and cultural values. Ecologically, they are integral to many aquatic and terrestrial food chains. Commercially, they are raised as a food source, and scientifically and educationally, they have served as an important model organism throughout the history of science and today dead frogs are used for dissections in anatomy classes. Culturally, frogs feature prominently in folklore, fairy tales, and popular culture. In addition, the unique morphology and behavior of frogs, including their calls and life cycle, add greatly to the wonder of nature for humans.

Although they are among the most diverse groups of vertebrates, populations of certain frog species are significantly declining.

Morphology and physiology

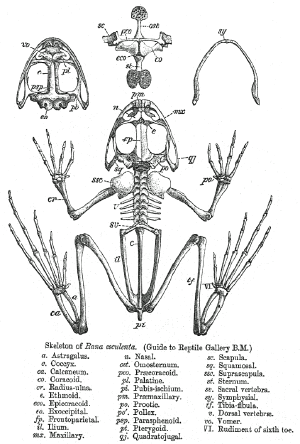

The morphology of frogs is unique among amphibians. Compared with the other two groups of amphibians (salamanders and caecilians), frogs are unusual because they lack tails as adults and their legs are more suited to jumping than walking.

The physiology of frogs is generally like that of other amphibians (and differs from other terrestrial vertebrates) because oxygen can pass through their highly permeable skin. This unique feature allows frogs to "breathe" largely through their skin. Because the oxygen is dissolved in an aqueous film on the skin and passes from there to the blood, the skin must remain moist at all times; this makes frogs susceptible to many toxins in the environment, some of which can similarly dissolve in the layer of water and be passed into their bloodstream. This may be a cause of the decline in frog populations.

Many characteristics are not shared by all of the approximately 5,250 described frog species. However, some general characteristics distinguish them from other amphibians. Frogs are usually well-suited to jumping, with long hind legs and elongated ankle bones. They have a short vertebral column, with no more than ten free vertebrae, followed by a fused tailbone (urostyle or coccyx), typically resulting in a tailless phenotype.

Frogs range in size from 10 millimeters (Brachycephalus didactylus of Brazil and Eleutherodactylus iberia of Cuba) to 300 millimeters (goliath frog, Conraua goliath, of Cameroon). The skin hangs loosely on the body because of the lack of loose connective tissue. Skin texture varies: it can be smooth, warty, or folded.

In the head area, frogs have three eyelid membranes: one is transparent to protect the eyes underwater, and two vary from translucent to opaque. Frogs have a tympanum on each side of the head, which is involved in hearing and, in some species, is covered by skin. Most frogs do, in fact, have teeth of a sort. They have a ridge of very small cone teeth around the upper edge of the jaw. These are called maxillary teeth. Frogs often also have what are called vomerine teeth on the roof of their mouth. They do not have anything that could be called teeth on their lower jaw, so they usually swallow their food whole. The so-called "teeth" are mainly used to hold the prey and keep it in place till they can get a good grip on it and squash their eyeballs down to swallow their meal. True toads, however, do not have any teeth.

Feet and legs

The structure of the feet and legs varies greatly among frog species, depending in part on whether they live primarily on the ground, in water, in trees, or in burrows. Frogs must be able to move quickly through their environment to catch prey and escape predators, and numerous adaptations help them do so.

Many frogs, especially those that live in water, have webbed toes. The degree to which the toes are webbed is directly proportional to the amount of time the species lives in the water. For example, the completely aquatic African dwarf frog (Hymenochirus sp.) has fully webbed toes, whereas the toes of White's tree frog (Litoria caerulea), an arboreal species, are only a half or a quarter webbed.

Arboreal frogs have "toe pads" to help grip vertical surfaces. These pads, located on the ends of the toes, do not work by suction. Rather, the surface of the pad consists of interlocking cells, with a small gap between adjacent cells. When the frog applies pressure to the toe pads, the interlocking cells grip irregularities on the substrate. The small gaps between the cells drain away all but a thin layer of moisture on the pad, and maintain a grip through capillarity. This allows the frog to grip smooth surfaces, and does not function when the pads are excessively wet (Emerson and Diehl 1980).

In many arboreal frogs, a small "intercalary structure" in each toe increases the surface area touching the substrate. Furthermore, since hopping through trees can be dangerous, many arboreal frogs have hip joints that allow both hopping and walking. Some frogs that live high in trees even possess an elaborate degree of webbing between their toes, as do aquatic frogs. In these arboreal frogs, the webs allow the frogs to "parachute" or control their glide from one position in the canopy to another (Harvey et al. 2002).

Ground-dwelling frogs generally lack the adaptations of aquatic and arboreal frogs. Most have smaller toe pads, if any, and little webbing. Some burrowing frogs have a toe extensionâa metatarsal tubercleâthat helps them to burrow. The hind legs of ground dwellers are more muscular than those of aqueous and tree-dwelling frogs.

Skin

Many frogs are able to absorb water directly through the skin, especially around the pelvic area. However, the permeability of a frog's skin can also result in water loss. Some tree frogs reduce water loss with a waterproof layer of skin. Others have adapted behaviors to conserve water, including engaging in nocturnal activity and resting in a water-conserving position. This position involves the frog lying with its toes and fingers tucked under its body and chin, respectively, with no gap between the body and substrate. Some frog species will also rest in large groups, touching the skin of the neighboring frog. This reduces the amount of skin exposed to the air or a dry surface, and thus reduces water loss. These adaptations only reduce water loss enough for a predominantly arboreal existence, and are not suitable for arid conditions.

Camouflage is a common defensive mechanism in frogs. Most camouflaged frogs are nocturnal, which adds to their ability to hide. Nocturnal frogs usually find the ideal camouflaged position during the day to sleep. Some frogs have the ability to change color, but this is usually restricted to shades of one or two colors. For example, White's tree frog varies in shades of green and brown. Features such as warts and skin folds are usually found on ground-dwelling frogs, where a smooth skin would not disguise them effectively. Arboreal frogs usually have smooth skin, enabling them to disguise themselves as leaves.

Certain frogs change color between night and day, as light and moisture stimulate the pigment cells and cause them to expand or contract.

Poison

Many frogs contain mild toxins that make them distasteful to potential predators. For example, all toads have large poison glandsâthe parotid glandsâlocated behind the eyes on the top of the head. Some frogs, such as some poison dart frogs, are especially toxic. The chemical makeup of toxins in frogs varies from irritants to hallucinogens, convulsants, nerve poisons, and vasoconstrictors. Many predators of frogs have adapted to tolerate high levels of these poisons. Others, including humans, may be severely affected.

Some frogs obtain poisons from the ants and other arthropods they eat (Saporito et al. 2004); others, such as the Australian Corroboree frogs (Pseudophryne corroboree and Pseudophryne pengilleyi), can manufacture an alkaloid not derived from their diet (Smith et al. 2002).

Some native people of South America extract poison from the poison dart frogs and apply it to their darts for hunting (Myers and Daly 1983), although few species are toxic enough to be used for this purpose. It was previously a misconception the poison was placed on arrows rather than darts. The common name of these frogs was thus changed from "poison arrow frog" to "poison dart frog" in the early 1980s.

Poisonous frogs tend to advertise their toxicity with bright colors, an adaptive strategy known as aposematism. There are at least two non-poisonous species of frogs in tropical America (Eleutherodactylus gaigei and Lithodytes lineatus) that mimic the coloration of dart poison frogs' coloration for self-protection (Batesian mimicry) (Savage 2002; Duellman 1978).

Because frog toxins are extraordinarily diverse, they have raised the interest of biochemists as a "natural pharmacy." The alkaloid epibatidine, a painkiller 200 times more potent than morphine, is found in some species of poison dart frogs. Other chemicals isolated from the skin of frogs may offer resistance to HIV infection (VanCompernolle et al. 2005). Arrow and dart poisons are under active investigation for their potential as therapeutic drugs (Phillipe and Angenot 2005).

The skin secretions of some toads, such as the Colorado River toad and cane toad, contain bufotoxins, some of which, such as bufotenin, are psychoactive, and have therefore been used as recreational drugs. Typically, the skin secretions are dried and smoked. Skin licking is especially dangerous, and appears to constitute an urban myth.

Respiration and circulation

The skin of a frog is permeable to oxygen and carbon dioxide, as well as to water. There are a number of blood vessels near the surface of the skin. When a frog is underwater, oxygen is transmitted through the skin directly into the bloodstream. On land, adult frogs use their lungs to breathe. Their lungs are similar to those of humans, but the chest muscles are not involved in respiration, and there are no ribs or diaphragm to support breathing. Frogs breathe by taking air in through the nostrils (causing the throat to puff out), and compressing the floor of the mouth, which forces the air into the lungs.

Frogs are known for their three-chambered heart, which they share with all tetrapods except birds and mammals. In the three-chambered heart, oxygenated blood from the lungs and de-oxygenated blood from the respiring tissues enter by separate atria, and are directed via a spiral valve to the appropriate vesselâaorta for oxygenated blood and pulmonary vein for deoxygenated blood. This special structure is essential to keeping the mixing of the two types of blood to a minimum, which enables frogs to have higher metabolic rates, and to be more active than otherwise.

Natural history

The life cycle of frogs, like that of other amphibians, consists of the main stages of egg, tadpole, metamorphosis, and adult. The reliance of frogs on an aquatic environment for the egg and tadpole stages gives rise to a variety of breeding behaviors that include the well-known mating calls used by the males of most species to attract females to the bodies of water that they have chosen for breeding. Some frogs also look after their eggsâand in some cases even the tadpolesâfor some time after laying.

Life cycle

The life cycle of a frog starts with an egg. A female generally lays frogspawn, or egg masses containing thousands of eggs, in water. While the length of the egg stage depends on the species and environmental conditions, aquatic eggs generally hatch within one week.

The eggs are highly vulnerable to predation, so frogs have evolved many techniques to ensure the survival of the next generation. Most commonly, this involves synchronous reproduction. Many individuals will breed at the same time, overwhelming the actions of predators; the majority of the offspring will still die due to predation, but there is a greater chance some will survive. Another way in which some species avoid the predators and pathogens eggs are exposed to in ponds is to lay eggs on leaves above the pond, with a gelatinous coating designed to retain moisture. In these species, the tadpoles drop into the water upon hatching. The eggs of some species laid out of water can detect vibrations of nearby predatory wasps or snakes, and will hatch early to avoid being eaten (Warkentin 1995). Some species, such as the cane toad (Bufo marinus), lay poisonous eggs to minimize predation.

Eggs hatch and the frogs continue life as tadpoles (occasionally known as polliwogs). Tadpoles are aquatic, lack front and hind legs, and have gills for respiration and tails with fins for swimming. Tadpoles are typically herbivorous, feeding mostly on algae, including diatoms filtered from the water through the gills. Some species are carnivorous at the tadpole stage, eating insects, smaller tadpoles, and fish. Tadpoles are highly vulnerable to predation by fish, newts, predatory diving beetles, and birds such as kingfishers. Cannibalism has been observed among tadpoles. Poisonous tadpoles are present in many species, such as cane toads. The tadpole stage may be as short as a week, or tadpoles may overwinter and metamorphose the following year in some species, such as the midwife toad (Alytes obstetricans) and the common spadefoot (Pelobates fuscus).

At the end of the tadpole stage, frogs undergo metamorphosis, in which they transition into adult form. Metamorphosis involves a dramatic transformation of morphology and physiology, as tadpoles develop hind legs, then front legs, lose their gills, and develop lungs. Their intestines shorten as they shift from an herbivorous to a carnivorous diet. Eyes migrate rostrally and dorsally, allowing for binocular vision exhibited by the adult frog. This shift in eye position mirrors the shift from prey to predator, as the tadpole develops and depends less upon a larger and wider field of vision and more upon depth perception. The final stage of development from froglet to adult frog involves apoptosis (programmed cell death) and resorption of the tail.

After metamorphosis, young adults may leave the water and disperse into terrestrial habitats, or continue to live in the aquatic habitat as adults. Almost all species of frogs are carnivorous as adults, eating invertebrates such as arthropods, annelids, and gastropods. A few of the larger species may eat prey such as small mammals, fish, and smaller frogs. Some frogs use their sticky tongues to catch fast-moving prey, while others capture their prey and force it into their mouths with their hands. There are a very few species of frogs that primarily eat plants (Silva et al. 1989). Adult frogs are themselves preyed upon by birds, large fish, snakes, otters, foxes, badgers, coatis, and other animals. Frogs are also eaten by people.

Reproduction of frogs

Once adult frogs reach maturity, they will assemble at a water source such as a pond or stream to breed. Many frogs return to the bodies of water where they were born, often resulting in annual migrations involving thousands of frogs. In continental Europe, a large proportion of migrating frogs used to die on roads, before special fences and tunnels were built for them.

Once at the breeding ground, male frogs call to attract a mate, collectively becoming a chorus of frogs. The call is unique to the species, and will attract females of that species. Some species have satellite males who do not call, but intercept females that are approaching a calling male.

The male and female frogs then undergo amplexus. This involves the male mounting the female and gripping her tightly. Fertilization is external: the egg and sperm meet outside of the body. The female releases her eggs, which the male frog covers with a sperm solution. The eggs then swell and develop a protective coating. The eggs are typically brown or black, with a clear, gelatin-like covering.

Most temperate species of frogs reproduce between late autumn and early spring. In the United Kingdom, most common frog populations produce frogspawn in February, although there is wide variation in timing. Water temperatures at this time of year are relatively low, typically between four and 10 degrees Celsius. Reproducing in these conditions helps the developing tadpoles because dissolved oxygen concentrations in the water are highest at cold temperatures. More importantly, reproducing early in the season ensures that appropriate food is available to the developing frogs at the right time.

Parental care

Although care of offspring is poorly understood in frogs, it is estimated that up to 20 percent of amphibian species may care for their young in one way or another, and there is a great diversity of parental behaviors (Crump 1996). Some species of poison dart frogs lay eggs on the forest floor and protect them, guarding the eggs from predation and keeping them moist. The frog will urinate on them if they become too dry. After hatching, a parent (the sex depends upon the species) will move them, on its back, to a water-holding bromeliad. The parent then feeds them by laying unfertilized eggs in the bromeliad until the young have metamorphosed.

Other frogs carry the eggs and tadpoles on their hind legs or back (e.g., the midwife toads). Some frogs even protect their offspring inside their own bodies. The male Australian pouched frog (Assa darlingtoni) has pouches along its side in which the tadpoles reside until metamorphosis. The female gastric-brooding frogs (genus Rheobatrachus) from Australia, now probably extinct, swallows its tadpoles, which then develop in the stomach. To do this, the gastric-brooding frog must stop secreting stomach acid and suppress peristalsis (contractions of the stomach). Darwin's frog (Rhinoderma darwinii) from Chile puts the tadpoles in its vocal sac for development. Some species of frog will leave a "babysitter" to watch over the frogspawn until it hatches.

Call

The call of a frog is unique to its species. Frogs call by passing air through the larynx in the throat. In most calling frogs, the sound is amplified by one or more vocal sacs, membranes of skin under the throat or on the corner of the mouth that distend during the amplification of the call. Some frog calls are so loud that they can be heard up to a mile away.

Some frogs lack vocal sacs, such as those from the genera Heleioporus and Neobatrachus, but these species can still produce a loud call. Their buccal cavity is enlarged and dome-shaped, acting as a resonance chamber that amplifies their call. Species of frog without vocal sacs and that do not have a loud call tend to inhabit areas close to flowing water. The noise of flowing water overpowers any call, so they must communicate by other means.

The main reason for calling is to allow males to attract a mate. Males call either individually or in a group called a chorus. Females of many frog species, for example Polypedates leucomystax, produce calls reciprocal to the males', which act as the catalyst for the enhancement of reproductive activity in a breeding colony (Roy 1997). A male frog emits a release call when mounted by another male. Tropical species also have a rain call that they make on the basis of humidity cues prior to a rain shower. Many species also have a territorial call that is used to chase away other males. All of these calls are emitted with the mouth of the frog closed.

A distress call, emitted by some frogs when they are in danger, is produced with the mouth open, resulting in a higher-pitched call. The effectiveness of the call is unknown; however, it is suspected the call intrigues the predator until another animal is attracted, distracting them enough for its escape.

Many species of frog have deep calls, or croaks. The onomatopoeic spelling is "ribbit." The croak of the American bullfrog (Rana catesbiana) is sometimes spelled "jug o' rum." Other examples are Ancient Greek brekekekex koax koax for probably Rana ridibunda, and the description in Rigveda 7:103.6 gómÄyur éko ajámÄyur ékaħ = "one [has] a voice like a cow's, one [has] a voice like a goat's."

Distribution and conservation status

The habitat of frogs extends almost worldwide, but they do not occur in Antarctica and are not present on many oceanic islands (Hogan and Hogan 2004). The greatest diversity of frogs occurs in the tropical areas of the world, where water is readily available, suiting frogs' requirements due to their skin. Some frogs inhabit arid areas such as deserts, where water may not be easily accessible, and rely on specific adaptations to survive. The Australian genus Cyclorana and the American genus Pternohyla will bury themselves underground, create a water-impervious cocoon, and hibernate during dry periods. Once it rains, they emerge, find a temporary pond and breed. Egg and tadpole development is very fast in comparison to most other frogs so that breeding is complete before the pond dries up. Some frog species are adapted to a cold environment; for instance the wood frog, which lives in the Arctic Circle, buries itself in the ground during winter when much of its body freezes.

Frog populations have declined dramatically since the 1950s: more than one-third of species are believed to be threatened with extinction and more than 120 species are suspected to be extinct since the 1980s (Stuart et al. 2004). Among these species are the golden toad of Costa Rica and the gastric-brooding frogs of Australia. Habitat loss is a significant cause of frog population decline, as are pollutants, climate change, the introduction of non-indigenous predators/competitors, and emerging infectious diseases including chytridiomycosis. Many environmental scientists believe that amphibians, including frogs, are excellent biological indicators of broader ecosystem health because of their intermediate position in food webs, permeable skins, and typically biphasic life (aquatic larvae and terrestrial adults) (Phillips 1994).

Taxonomy

Frogs and toads are broadly classified into three suborders: Archaeobatrachia, which includes four families of primitive frogs; Mesobatrachia, which includes five families of more evolutionary intermediate frogs; and Neobatrachia, by far the largest group, which contains the remaining 24 families of "modern" frogs, including most common species throughout the world. Neobatrachia is further divided into Hyloidea and Ranoidea (Ford and Cannatella 1993).

This classification is based on such morphological features as the number of vertebrae, the structure of the pectoral girdle, and the [[morphology] of tadpoles. While this classification is largely accepted, relationships among families of frogs are still debated. Due to the many morphological features that separate the frogs, there are many different systems for the classification of the anuran suborders. These different classification systems usually split the Mesobatrachian suborder. Future studies of molecular genetics should soon provide further insights to the evolutionary relationships among frog families (Faivovich et al. 2005).

As suggested by their names, the Archaeobatrachians are considered the most primitive of frogs. These frogs have morphological characteristics which are found mostly in extinct frogs, and are absent in most of the modern frog species. Most of these characteristics are not common between all the families of Archaeobatrachians, or are not absent from all the modern species of frog. However all Archarobatrachians have free vertebrae, whereas all other species of frog have their ribs fused to their vertebrae.

The Neobatrachians comprise what is considered the most modern species of frog. Most of these frogs have morphological features than are more complex than those of the Mesobatrachians and Archaeobatrachians. The Neobatrachians all have a palatine bone, which is a bone which braces the upper jaw to the neurocranium. This is absent in all Archaeobatrachians and some Mesobatrachians. The third distal carpus is fused with the remaining carpal bones. The adductor longus muscle is present in the Neobatrachians, but absent in the Archaeobatrachians and some Mesobatrachians. It is believed to have differentiated from pectineus muscle, and this differentiation has not occurred in the primitive frogs.

The Mesobatrachians are considered the evolutionary link between the Archaeobatrachians and the Neobatrachians. The families within the Mesobatrachian suborder generally contain morphological features typical of both the other suborders. For example, the palatine bone is absent in all Archaeobatrachians, and present in all Neobatrachians. However, within the Mesobatrachians families, it can be dependent on the species as to whether the palatine bone is present.

Some species of anurans hybridize readily. For instance, the edible frog (Rana esculenta) is a hybrid of the pool frog (R. lessonae) and the marsh frog (R. ridibunda). Bombina bombina and Bombina variegata similarly form hybrids, although these are less fertile, giving rise to a hybrid zone.

Origin

The earliest known (proto) frog is Triadobatrachus]] massinoti, from the 250-million-year-old early Triassic of Madagascar. The skull is frog-like, being broad with large eye sockets, but the fossil has features diverging from modern amphibians. These include a different ilium, a longer body with more vertebrae, and separate vertebrae in its tail (whereas in modern frogs, the tail vertebrae are fused, and known as the urostyle or coccyx). The tibia and fibula bones are unfused and separate, making it probable Triadobatrachus was not an efficient leaper.

Another fossil frog, discovered in Arizona and called Prosalirus bitis, was uncovered in 1985, and dates from roughly the same time as Triadobatrachus. Like Triadobatrachus, Prosalirus did not have greatly enlarged legs, but had the typical three-pronged pelvic structure. Unlike Triadobatrachus, Prosalirus had already lost nearly all of its tail.

The earliest true frog is Vieraella herbsti, from the early Jurassic (188â213 million years ago). It is known only from the dorsal and ventral impressions of a single animal and was estimated to be 33Â mm from snout to vent. Notobatrachus degiustoi from the middle Jurassic is slightly younger, about 155â170 million years old. It is likely the evolution of modern Anura was completed by the Jurassic period. The main evolutionary changes involved the shortening of the body and the loss of the tail.

The earliest full fossil record of a modern frog is of sanyanlichan, which lived 125 million years ago and had all modern frog features, but bore 9 presacral vertebrae instead of the 8 of modern frogs, apparently still being a transitional species.

Frog fossils have been found on all continents, including Antarctica.

Uses in agriculture and research

Frogs are raised commercially for several purposes. Frogs are used as a food source; frog legs are a delicacy in China, France, the Philippines, the north of Greece, and in many parts of the Southern United States, especially Louisiana. Dead frogs are sometimes used for dissections in high school and university anatomy classes, often after being injected with colored plastics to enhance the contrast between the organs. This practice has declined in recent years with the increasing concerns about animal welfare.

Frogs have served as important model organisms throughout the history of science. Eighteenth-century biologist Luigi Galvani discovered the link between electricity and the nervous system through studying frogs. The African clawed frog or platanna (Xenopus laevis) was first widely used in laboratories in pregnancy assays in the first half of the twentieth century. When human chorionic gonadotropin, a hormone found in substantial quantities in the urine of pregnant women, is injected into a female X. laevis, it induces them to lay eggs. In 1952, Robert Briggs and Thomas J. King cloned a frog by somatic cell nuclear transfer, the same technique later used to create Dolly the Sheep; their experiment was the first time successful nuclear transplantation had been accomplished in metazoans (Di Berardino).

Frogs are used in cloning research and other branches of embryology because frogs are among the closest living relatives of man to lack egg shells characteristic of most other vertebrates, and therefore facilitate observations of early development. Although alternative pregnancy assays have been developed, biologists continue to use Xenopus as a model organism in developmental biology because it is easy to raise in captivity and has a large and easily manipulatable embryo. Recently, X. laevis is increasingly being displaced by its smaller relative X. tropicalis, which reaches its reproductive age in five months rather than one to two years (as in X. laevis) (NIH 2001), facilitating faster studies across generations.

Frogs in popular culture

Frogs feature prominently in folklore, fairy tales ,and popular culture. They tend to be portrayed as benign, ugly, clumsy, but with hidden talents. Examples include Michigan J. Frog, The Frog Prince, and Kermit the Frog. Michigan J. Frog, featured in a Warner Brothers cartoon, only performs his singing and dancing routine for his owner. Once another person looks at him, he will return to a frog-like pose. The Frog Prince is a fairy tale of a frog who turns into a handsome prince once kissed. Kermit the Frog, on the other hand, is a conscientious and disciplined character of Sesame Street and The Muppet Show; while openly friendly and greatly talented, he is often portrayed as cringing at the fanciful behavior of more flamboyant characters.

The Moche people of ancient Peru worshipped animals and often depicted frogs in their art (Berrin and Larco Museum 1997). Vietnamese people have a saying: "Ếch ngá»i Äáy giếng coi trá»i bằng vung" ("Sitting at the bottom of wells, frogs think that the sky is as wide as a lid") which ridicules someone who has limited knowledge yet is arrogant.

Cited references

- Berrin, K., and Larco Museum. 1997. The Spirit of Ancient Peru: Treasures from the Museo Arqueológico Rafael Larco Herrera. New York: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0500018022.

- Crump, M. L. 1996. Parental care among the Amphibia. Advances in the Study of Behavior 25: 109â144.

- Di Berardino, M. A. n.d. Robert W. Briggs Biographical Memoir, December 10, 1911âMarch 4, 1983. National Academy of Sciences. Retrieved January 14, 2008.

- Duellman, W. E. 1978. The Biology of an Equatorial Herpetofauna in Amazonian Ecuador. University of Kansas Museum of Natural History Miscellaneous Publication 65: 1â352.

- Emerson, S. B., and D. Diehl. 1980. Toe pad morphology and mechanisms of sticking in frogs. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 13(3): 199â216.

- Ford, L. S., and D. C. Cannatella. 1993. The major clades of frogs. Herpetological Monographs 7: 94â117.

- Haddad, C. F. B., P. C. A. Garcia, D. R. Frost, J. A. Campbell, and W. C. Wheeler. 2005. Systematic review of the frog family Hylidae, with special reference to Hylinae: Phylogenetic analysis and taxonomic revision. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 294: 1â240.

- Harvey, M. B, A. J. Pemberton, and E. N. Smith. 2002. New and poorly known parachuting frogs (Rhacophoridae : Rhacophorus) from Sumatra and Java. Herpetological Monographs 16: 46â92.

- Hogan, D., and M. Hogan. 2004. Freaky frogs. National Geographic Explorer. Retrieved January 14, 2008.

- Myers, C. W., and J. W. Daly. 1983. Dart-poison frogs. Scientific American 248: 120â133.

- National Institutes of Health (NIH). 2001. Developing the potential of Xenopus tropicalis as a genetic model. National Institutes of Health. Retrieved January 14, 2008.

- Phillipe, G., and L. Angenot. 2005. Recent developments in the field of arrow and dart poisons. J Ethnopharmacol 100(1â2): 85â91.

- Phillips, K. 1994. Tracking the Vanishing Frogs. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 0140246460.

- Roy, D. 1997. Communication signals and sexual selection in amphibians. Current Science 72: 923â927.

- Saporito, R. A., H. M. Garraffo, M. A. Donnelly, A. L. Edwards, J. T. Longino, and J. W. Daly. 2004. Formicine ants: An arthropod source for the pumiliotoxin alkaloids of dendrobatid poison frogs. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science 101: 8045â8050.

- Savage, J. M. 2002. The Amphibians and Reptiles of Costa Rica. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226735370.

- Silva, H. R., M. C. Britto-Pereira, and U. Caramaschi. 1989. Frugivory and seed dispersal by Hyla truncate, a neotropical treefrog. Copeia 3: 781â783.

- Smith, B. P., M. J. Tyler, T. Kaneko, H. M> Garraffo, T. F. Spande, and J. W. Daly. 2002. Evidence for biosynthesis of pseudophrynamine alkaloids by an Australian myobatrachid frog (pseudophryne) and for sequestration of dietary pumiliotoxins. J Nat Prod 65(4): 439â447.

- Stuart, S. N., J. S. Chanson, N. A. Cox, B. E. Young, A. S. L. Rodrigues, D. L. Fischman, and R. W. Waller. 2004. Status and trends of amphibian declines and extinctions worldwide. Science 306: 1783â1786.

- VanCompernolle, S. E., R. J. Taylor, K. Oswald-Richter, J. Jiang, B. E. Youree, J. H. Bowie, M. J. Tyler, M. Conlon, D. Wade, C. Aiken, and T. S. Dermody. 2005. Antimicrobial peptides from amphibian skin potently inhibit Human Immunodeficiency Virus infection and transfer of virus from dendritic cells to T cells. Journal of Virology 79: 11598â11606.

- Warkentin, K. M. 1995. Adaptive plasticity in hatching age: a response to predation risk trade-offs. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 92: 3507â3510.

General references

- Cogger, H. G., R. G. Zweifel, and D. Kirschner. 2004. Encyclopedia of Reptiles & Amphibians, 2nd ed. Fog City Press. ISBN 1877019690.

- Estes, R., and O. A. Reig. 1973. The early fossil record of frogs: A review of the evidence. In Evolutionary Biology of the Anurans: Contemporary Research on Major Problems, ed. J. L. Vial, 11â63. Columbia: University of Missouri Press.

- Gissi, C., D. San Mauro, G. Pesole, and R. Zardoya. 2006. Mitochondrial phylogeny of Anura (Amphibia): A case study of congruent phylogenetic reconstruction using amino acid and nucleotide characters. Gene 366: 228â237.

- Holman, J. 2004. Fossil Frogs and Toads of North America. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0253342805.

- San Mauro, D., M. Vences, M. Alcobendas, R. Zardoya, and A. Meyer. 2005. Initial diversification of living amphibians predated the breakup of Pangaea. American Naturalist 165: 590â599.

- Tyler, M. J. 1994. Australian Frogs: A Natural History. Reed Books.

External links

All links retrieved April 15, 2024.

- The Whole Frog Project â Virtual frog dissection and anatomy.

- Amphibia Web.

- Amphibian photo gallery by scientific name â features many unusual frogs.

| Chordata - Amphibia - Families of Anura | |

|---|---|

|

Allophrynidae - Amphignathodontidae - Arthroleptidae - Ascaphidae - Bombinatoridae - Brachycephalidae - Bufonidae - Centrolenidae - Dendrobatidae - Discoglossidae - Heleophrynidae - Hemisotidae - Hylidae - Hyperoliidae - Leiopelmatidae - Leptodactylidae - Mantellidae - Megophryidae - Microhylidae - Myobatrachidae - Nasikabatrachidae - Pelobatidae - Pelodytidae - Pipidae - Ranidae - Rhacophoridae - Rhinodermatidae - Rhinophrynidae - Scaphiopodidae - Sooglossidae | |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.