Basilica

A basilica, in the Catholic and Orthodox traditions, is a church building that is especially honored either because of its antiquity, association with a saint, or importance as a center of worship.

The Latin word basilica was originally used to describe a public building, usually located at the center of a Roman town (forum). Public basilicas appeared in the second century B.C.E. The Roman basilica was a large roofed hall built for transacting business and disposing of legal matters. In the early Imperial period, palaces also contained basilicas for large audiences.

After the Roman Empire became Christianized, the term "basilica" referred to a large and important church that had special ceremonial rites ascribed by a patriarch or pope, thus the word retains two senses: One architectural, the other ecclesiastical. The Emperor Constantine I built a basilica of this type in his palace complex at Trier. Typically, a Christian basilica of the fourth or fifth century stood behind its entirely enclosed forecourt ringed with a colonnade or arcade. This became the architectural ground plan of the original St. Peter's Basilica in Rome, which was replaced in the fifteenth century by a great modern church on a new plan reminiscent of the previous one. Gradually, in the early Middle Ages, there emerged the massive Romanesque churches, which still retained the fundamental plan of the basilica.

In the Western Church, a papal brief is required to attach the privilege of a church being termed a basilica. Western churches designated as patriarchal basilicas must possess a papal throne and a papal high altar from which no one may celebrate Mass without the pope's permission.

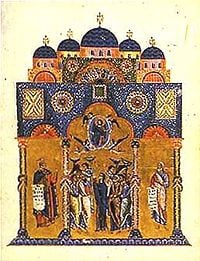

Basilicas are also primary ecclesiastical structures in the Eastern Orthodox Church. Architecturally, these were long rectangular structures divided into three or five aisles by rows of columns in order to accommodate the Liturgy of the Faithful. Prime examples of the Eastern-Orthodox basilica are the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, originally Emperor Justinian I's great Church of the Divine Wisdom, and the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, also called the Church of the Resurrection by Eastern Christians, within the walled Old City of Jerusalem.

A number of basilicas have become significant pilgrimage sites, particularly among the many that were built above a Confession (Burial Place of a Martyr).

Basilicas in architecture

In pre-Christian Roman architecture, the basilica was a large roofed hall erected for transacting business and disposing of legal matters. Such buildings usually contained interior colonnades that divided the space, giving aisles or arcaded spaces at one or both sides, with an apse at one end (or less often at each end), where the magistrates sat, often on a slightly raised dais. The central aisle tended to be wide and was higher than the flanking aisles, so that light could penetrate through the clerestory windows.

The oldest known basilica, the Basilica Porcia, was built in Rome in 184 B.C.E. by Cato the Elder during the time he was censor. Other early examples include the one at Pompeii (late-second century B.C.E.). Probably the most splendid Roman basilica is the one constructed for traditional purposes during the reign of the pagan emperor Maxentius and finished by Constantine after 313. As early as the time of Augustus, a public basilica for transacting business had been part of any settlement that considered itself a city, used like the late medieval covered market houses of northern Europe (where the meeting room, for lack of urban space, was set above the arcades).

Basilicas in the Roman Forum include:

- Basilica Porcia: First basilica built in Rome (184 B.C.E.), erected on the personal initiative and financing of the censor M. Porcius Cato as an official building for the tribunes of the plebs

- Aemilian Basilica, built by the censor Aemilius Lepidus in 179 B.C.E.

- Julian Basilica, completed by Augustus

- Basilica Opimia, erected probably by the consul L. Opimius in 121 B.C.E., at the same time that he restored the temple of Concord (Platner, Ashby 1929)

- Basilica Sempronia, built by the censor Marcus Sempronius Gracchus in 169 B.C.E.

- Basilica of Maxentius and Constantine (308-after 313)

In the early Imperial period, a basilica for large audiences also became a feature in the palaces. Seated in the tribune of his basilica, the great man would meet his dependent clientes early every morning.

A private basilica excavated at Bulla Regia (Tunisia), in the "House of the Hunt," dates from the first half of the fourth century. Its reception or audience hall is a long rectangular nave-like space, flanked by dependent rooms that mostly also open into one another, ending in a circular apse, with matching transept spaces. The "crossing" of the two axes was emphasized with clustered columns.

Christianizing the Roman basilica

In the fourth century, Christians were prepared to build larger and more handsome edifices for worship than the furtive meeting places they had been using. Architectural formulas for temples were unsuitable, not simply for their pagan associations, but because pagan cult worship and sacrifices occurred outdoors under the open sky in the sight of the gods, with the temple, housing the cult figures and the treasury, as a backdrop. The usable model at hand, when the first Christian Emperor, Constantine I, wanted to memorialize his imperial piety, was the familiar conventional architecture of the basilicas. These had a center nave with one aisle at each side and an apse at one end: On this raised platform sat the bishop and priests.

Constantine built a basilica of this type in his palace complex at Trier, later very easily adopted for use as a church. It is a long rectangle two stories high, with ranks of arch-headed windows one above the other, without aisles (no mercantile exchange in this imperial basilica) and at the far end, beyond a huge arch, the apse in which Constantine held state. Exchange the throne for an altar, as was done at Trier, and you had a church. Basilicas of this type were built not only in Western Europe but in Greece, Syria, Egypt, and Palestine. Good early examples of the architectural basilica are the Church of the Nativity at Bethlehem (sixth century), the church of St. Elias at Thessalonica (fifth century), and the two great basilicas at Ravenna.

The first basilicas with transepts were built under the orders of Constantine, both in Rome and his "New Rome," Constantinople.

Gregory Nazianzen was the first to point out its resemblance to a cross. Thus, a Christian symbolic theme was applied quite naturally to a form borrowed from pagan civil precedents. In the later fourth century, other Christian basilicas were built in Rome: Santa Sabina, St. John Lateran and St. Paul's-outside-the-Walls (fourth century), and later San Clemente (sixth century).

A Christian basilica of the fourth or fifth century stood behind its entirely enclosed forecourt ringed with a colonnade or arcade, like the stoa or peristyle that was its ancestor or like the cloister that was its descendant. This forecourt was entered from outside through a range of buildings along the public street. This was the architectural ground plan of St. Peter's Basilica in Rome, until first the forecourt, then all of it was swept away in the fifteenth century to make way for a great modern church on a new plan.

In most basilicas, the central nave is taller than the aisles, forming a row of windows called a clerestory. Some basilicas in the Near East, particularly those of Georgia and Armenia, have a central nave only slightly higher than the two aisles and a single pitched roof covering all three. The result is a much darker interior. This plan is known as the "oriental basilica."

Famous existing examples of churches constructed in the ancient basilica style include:

- The Greek Orthodox church at Saint Catherine's Monastery on the Sinai Peninsula in Egypt, at the mouth of an inaccessible gorge at the foot of Mount Sinai, one of the oldest continuously functioning Christian monasteries in the world. It is a UNESCO World Heritage site.

- Basilica of San Vitale, the most famous monument of Ravenna, Italy and is one of the most important examples of Byzantine Art and architecture in western Europe. The building is one of eight Ravenna structures on the UNESCO World Heritage list.

Gradually, in the early Middle Ages, there emerged the massive Romanesque churches, which still retained the fundamental plan of the basilica.

The ecclesiastical basilica

The early Christian basilicas were the cathedral churches of the bishop, on the model of the secular basilicas, and their growth in size and importance signaled the gradual transfer of civic power into episcopal hands, underway in the fifth century. Basilicas in this sense are divided into classes: The major ("greater"), and the minor basilicas.

As of March 26, 2006, there were no less than 1,476 Papal basilicas in the Roman Catholic Church, of which the majority were in Europe (526 in Italy alone, including all those of elevated status; 166 in France; 96 in Poland; 94 in Spain; 69 in Germany; 27 in Austria; 23 in Belgium; 13 in the Czech Republic; 12 in Hungary; 11 in the Netherlands); less than ten in many other countries, many in the Americas (58 in the United States, 47 in Brazil, 41 in Argentina, 27 in Mexico, 25 in Colombia, 21 in Canada, 13 in Venezuela, 12 in Peru, etc.); and fewer in Asia (14 in India, 12 in the Philippines, nine in the Holy Land, some other countries (one or two), Africa (several countries one or two), and Oceania (Australia four, Guam one).

The privileges attached to the status of Roman Catholic basilica, which is conferred by Papal Brief, include a certain precedence before other churches, the right of the conopaeum (a baldachin resembling an umbrella; also called umbraculum, ombrellino, papilio, sinicchio, etc.) and the bell (tintinnabulum), which are carried side by side in procession at the head of the clergy on state occasions, and the cappa magna which is worn by the canons or secular members of the collegiate chapter when assisting at the Divine Office.

Churches designated as patriarchal basilicas, in particular, possess a papal throne and a papal high altar from which no one may celebrate Mass without the pope's permission.

Numerous basilicas are notable shrines, often even receiving significant pilgrimage, especially among the many that were built above a Confession (Burial Place of a Martyr).

The Papal basilicas

To this class belong just four great churches of Rome, which among other distinctions have a special "holy door" and to which a visit is always prescribed as one of the conditions for gaining the Roman Jubilee. Pope Benedict XVI renamed these basilicas from Patriarchal to Papal.

- St. John Lateran is the cathedral of the Bishop of Rome: The Pope and hence is the only one called "archbasilica" (full name: Archbasilica of the Most Holy Saviour, St. John the Baptist, and St. John the Evangelist at the Lateran). It is also called the Lateran basilica.

- St. Peter's Basilica is symbolically assigned to the now abolished position of Patriarch of Constantinople. It is also known as the Vatican basilica.

- St. Paul outside the Walls, technically a parish church, is assigned to the Patriarch of Alexandria. It is also known as the Ostian basilica.

- St. Mary Major is assigned to the Patriarch of Antioch. It is also called the Liberian basilica.

While the major basilicas form a class that outranks all other churches, even other papal ones, all other so called "minor" basilicas, as such do not form a single class, but belong to different classes, most of which also contain non-basilicas of equal rank; within each diocese, the bishop's cathedral takes precedence over all other basilicas. Thus, after the major basilicas come the primatial churches, the metropolitan, other (e.g. suffragan) cathedrals, collegiate churches, etc.

The four major basilicas above and the minor basilica of St Lawrence outside the Walls (representing the Patriarch of Jerusalem) are collectively called the "patriarchal basilicas." This is representative of the great ecclesiastical provinces of the world symbolically united in the heart of Christendom.

Minor basilicas

The lesser minor basilicas are the vast majority, including some cathedrals, many technically parish churches, some shrines, some abbatial or conventual churches. The Cathedral Basilica of Notre-Dame de Québec in Quebec City was the first basilica in North America, designated by Pope Pius IX in 1874. St. Adalbert's Basilica in Buffalo, New York, was the first Basilica in the United States of America made so in 1907, by Pope Pius X. In Colombia, the Las Lajas Cathedral has been a minor basilica since 1954. The Basilica of Our Lady of Peace of Yamoussoukro, Cote d'Ivoire is reported slightly larger than St. Peter's Basilica.

There has been a pronounced tendency of late years to add to their number. In 1960, Pope John XXIII even declared Generalisimo Franco's grandiose tomb in the monumental Valley of the Fallen near Madrid, a basilica. In 1961, Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo, in Carmel, California (United States) was designated as a Minor Basilica by Pope John XXIII.

The Orthodox basilica

The Orthodox church building serves basically as the architectural setting for the liturgy, for which converted houses originally served this purpose. In the fourth and fifth centuries, buildings were erected to facilitate baptism and burial and to commemorate important events in the lives of Christ and the saints. However, it was the building designed primarily to accommodate the celebration of the Eucharist that became the typical Christian structure—the church as we think of it today.

As early as the fifth century, church plans varied from one part of the empire to another. A church in, say, Syria or Greece and one in Italy or Egypt, were likely to differ noticeably. Most of these, however, were basilicas, long rectangular structures divided into three or five aisles by rows of columns running parallel to the main axis, with a semi-cylindrical extension—an apse—at one end (usually the eastern) of the nave, or central aisle. The altar stood in front of the central apse. A low barrier separated the bema—the area around the altar—from the rest of the church for the use of the clergy. Sometimes a transverse space—the transept—intervened between the aisles and apsidal wall. Just inside the entrance was the narthex, a chamber where the catechumens stood during the Liturgy of the Faithful. In front of the entrance was a walled courtyard, or atrium. The roof was raised higher over the nave than over the side aisles, so that the walls resting on the columns of the nave could be pierced with windows. From the beginning, less attention was paid to the adornment of the church's exterior than to the beautification of its interior.

The flat walls and aligned columns of a basilica define spatial volumes that are simple and mainly rectangular (except for the apse); they also are rationally interrelated and in proportion to each other, with a horizontal "pull" toward the bema, where the clergy would be seen framed by the outline of the apse. More dramatic spatial effects were made possible when vaults and domes, which had been common in baptisteries, mausolea, and martyria, were applied to churches.

The dome was put to its most spectacular use in Constantinople, in Emperor Justinian I's great Church of the Divine Wisdom—the Hagia Sophia—raised in the phenomenally short time of less than six years (532-537). For many centuries, it was the largest church in Christendom. The architects, Anthemius and Isidorus, created a gigantic, sublime space bounded on the lower levels by colonnades and walls of veined marble and overhead by membranous vaults that seem to expand like parachutes opening against the wind. The climactic dome has 40 closely spaced windows around its base and on sunny days appears to float on a ring of light. The Hagia Sophia was later transformed into a mosque.

The Hagia Sophia is sometimes called a "domed basilica," but the phrase minimizes the vast differences between the dynamism of its design and the comparatively static spaces of a typical basilica. No church would be constructed to rival Hagia Sophia; but the dome was established as a hallmark of Byzantine architecture, and it infused church design with a more mystical geometry. In a domed church, one is always conscious of the hovering hemisphere, which determines a vertical axis around which the subordinate spaces are grouped and invites symbolic identification with the "dome of heaven."

Another famous Orthodox basilica is the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, also called the Church of the Resurrection by Eastern Christians, a Christian church within the walled Old City of Jerusalem. The ground on which the church stands is venerated by most Christians as Golgotha, the Hill of Calvary, where the New Testament says that Jesus was crucified. It is said to also contain the place where Jesus was buried (the sepulchre). The church has been an important pilgrimage destination since the fourth century. Today, it serves as the headquarters of the Orthodox Patriarch of Jerusalem and the Catholic Archpriest of the Basilica of the Holy Sepulchre.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Hibbert, Christopher. The House of Medici: Its Rise and Fall. Harper Perennial, 1999. ISBN 978-0688053390

- Pergola, Philippe.Christian Rome: Past and Present: Early Christian Rome Catacombs and Basilicas. Getty Trust Publications, 2002. ISBN 8881621010

- Scotti, R.A. Basilica: The Splendor and the Scandal: Building St. Peter's. Plume, 2007. ISBN 978-0452288607

- Tucker, Gregory W. America's Church: Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception. Our Sunday Visitor, 2000. ISBN 978-0879737009

- Vio Ettore, & Evans, Huw. The Basilica of St. Mark in Venice'.' Riverside Book Company, 2000. ISBN 978-1878351555

External links

All links retrieved December 31, 2021.

- Architecture of the basilica, well illustrated.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.