Basilides (early second century) was a Gnostic Christian religious teacher in Alexandria, Egypt. He taught a dualistic theology that emphasized spiritual realities and promoted a complex understanding of the origins of the universe and the place of humans in it. His followers formed the Gnostic sect known as the Basilideans.

Basilides was a pupil of a hearer of St. Peter, Glaucias by name, and may also have been a disciple of Menander of Antioch. He taught at Alexandria during the reign of Hadrian (117â138). Some believe that the best known second-century Gnostic teacher, Valentinus, studied with Basilides and took his teachings to Rome where he further developed and popularized them. Criticism of Basilides' movement by his detractors as engaging in immoral sexual practices is dismissed by most modern scholars as unfounded by evidence.

Historians know of Basilides and his teachings only through the writings of his detractors, especially Irenaeus, Clement of Alexandria, and Hippolytus of Rome, whose accounts of his teachings do not always agree with each other. He reportedly spoke of an utterly transcendent God beyond even the concept of being, to whom he gave the name Abraxas. The Jewish Creator God, in his view, was not identical to this Unknown Father, but was a lower angelic power. Basilides taught that Jesus was the savior, but he did not come to atone for sin by dying on the Cross. Instead, he came to uplift humans to their original state of bliss through the process of gnosis and did not possess an actual physical body.

Many of the concepts described by the Church Fathers as belonging to Basilides are found in the collection of ancient Gnostic works discovered in Nag Hammadi, Egypt in the mid twentieth century. Some of Basilides' teachings, or those of his followers, also influenced later Egyptian mystical and magic traditions, and may have had an impact on Jewish mystical ideas as well. Several twentieth-century writers have also drawn upon Basilidean traditions.

Teachings

Basilides reportedly wrote 24 books of exegesis based on the Christian Gospels, as well as various psalms and prayers. However, since practically nothing of Basilides' own writings has survived and he is not mentioned in the Gnostic sources, the teaching of this patriarch of Gnosticism must be gleaned primarily from his Christian opponents. Unfortunately, the accounts of Basilidesâ theology provided by such writers as Clement of Alexandria, Tertullian, Hippolytus of Rome, and Irenaeus do not always agree with each other. According to Irenaeus, for example, Basilides was a dualist and an emanationist, while according to Hippolytus, a pantheistic evolutionist. In addition, Ireneaus describes the highest being as the Unborn Father, and Epiphanius and Tertullian give him the name Abraxas. Hippolytus, however, says Abraxas is the highest Archon and not identical with the Unborn One. Each of these views of Basilides' teachings is summarized below:

Ireneaus' view

According to Irenaeus, Basilides taught that Nous (mind) was the first to be born from the Unborn Father. From Nous was born Logos (reason); from Logos came Phronesis (prudence); from Phronesis was born Sophia (wisdom) and Dynamis (strength); and from Phronesis and Dynamis came the Virtues, Principalities, and Archangels. These angelic hosts in turn created the highest heaven; their descendants created the second heaven; from the denizens of the second heaven came the inhabitants of third heaven, and so on, until the number of the heavens reached 365. Hence, the year has as many days as there are heavens.

The angels, who control the lowest, or visible heaven, brought about all things and peoples that exist in our world. The highest of these angels is identical with the God of the Jews. However, as this deity wished to subject the Gentiles to his own chosen people, the other angelic principalities strongly opposed him.

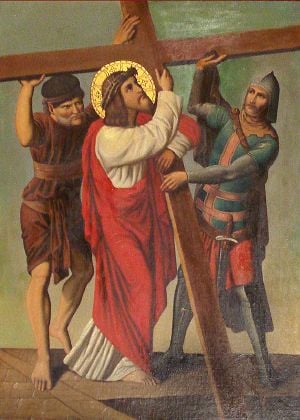

To deliver humans from the power of the angelic beings who created the visible world, the Unborn and Nameless Father sent his first-born, Nous (known to history as the Christ). Christ seemed to be a man and to have performed miracles, but he was actually beyond all association with the physical body. Indeed, it was not Christ who suffered, but rather Simon of Cyrene, who was constrained to carry the cross for him, assumed Jesus' form, and was crucified in Christ's place. As Simon was crucified, Jesus returned to His Father, laughing at those who mourned his suffering. Through gnosis (knowledge) of Christ, the souls of men are saved, but their bodies perish. Thus, there is no such thing as physical resurrection, for the flesh is beyond redemption and only the spirit requires salvation.

From the writings of Epiphanius and Tertullian these additional concepts can be derived: The highest deityâthat is, the Unborn Fatherâbears the mystical name Abraxas, as origin of the 365 heavens. The angels that made the world formed it out of eternal matter, but matter is the principle of all evil. Jesus Christ thus only appeared to be a physical man, but was in fact a purely spiritual being. Moreover, to undergo martyrdom in imitating Christ is useless, for it is to die for Simon of Cyrene, not for Christ.

Hippolytus' view

Hippolytus of Rome sets forth a somewhat different version of the doctrine of Basilides. Some commentators account for the difference by the idea that Hipppoytus' version was based on later Basilidean writers rather than Basilides himself. Hippolytus provides the following fragment reportedly from the pen of Basilides:

There was when naught was: nay, even that "naught" was not aught of things that are... Naught was, neither matter, nor substance, nor voidness of substance, nor simplicity, nor impossibility of composition, nor inconceptibility, imperceptibility, neither man, nor angel, nor god. In sum, anything at all for which man has ever found a name, nor by any operation which falls within range of his perception or conception.

There was thus a time when nothing existed, neither matter nor form (although time itself is also included in this state of non-being). Even the deity Himself was beyond existence. This deity is referred to as the "Not-Being God" (ouk on theos), whom Aristotle called the "Thought of thought" (noesis tes noeseos)âwithout consciousness, perception, purpose, passion, or desire. From this "Not-Being God" came the seed that became the world. From this, Panspermia, as in the parable of the mustard seed, all things eventually evolved.

According to Hippolytus, in contrast to what Irenaeus claimed, Basilides distinctly rejected both emanation and the eternity of matter: "God spoke and it was." The transition from Non-Being to Being is accounted for through the idea of the Panspermia (All-seed), which contained in itself three types of elements: the refined Leptomeres, the less spiritual Pachymeres, and the impure Apokatharseos deomenon.

These three "filiations" of the Panspermia all ultimately return to the Not-Being God, but each reaches Him in a different way. The first, most refined, elements rose at once and flew with the swiftness of thought to Him. The second wished to imitate the first, but failed because they were too gross and heavy. They thus took up wings, which are provided by the Holy Spirit, and almost reached the Not-Being God, but descended again and became the "Boundary Spirit" (Methorion Pneuma) between the Supermundane and the Mundane. The third element, meanwhile, remained trapped in the Panspermia.

Now there arose in the Panspermia the Great Archon, or Ruler, similar to the Demiurge in other Gnostic literature. He sped upwards, and, thinking there was nothing above and beyondâalthough he was still contained in the Panspermiaâfancied himself Lord and Master of all things. He created for himself a Son out of the Panspermia. This was the Christ. Being amazed at the beauty of his Son, who was greater than his Father, the Great Archon made him sit at his right hand. Together, these two created the ethereal heavens, which reach unto the Moon. The sphere where the Great Archon rules is called the Ogdoad. The same process is then repeated, and thus evolves a second Archon and his Son. The sphere where they rule is the Hebdomad, beneath the Ogdoad.

This sets the stage for the grosser elements, the third "filiation," also to be raised out of the Panspermia to the Not-Being God. This takes place though the Gospel, perceived not only as a teaching, but a powerful spiritual principality. From Adam to Moses, the Archon of the Ogdoad had reigned (Romans 5:14). In Moses and the prophets, the Archon of the Hebdomad had reigned, known to history as Yahweh, the God of the Jews. Now in the third period, the Gospel must reign, forming a crucial and transcendent link to the No-Being God Himself.

The preexistent Gospel was first made known through the Holy Spirit to the Son of the Archon of the Ogdoad (Christ). The Son told this to his Father, who was astounded by its truth and finally admitted his pride in thinking himself to be the Supreme Deity. The Son of the Archon of the Ogdoad then informed the Son of the Archon of the Hebdomad, and he again told his Father. Thus both spheres, including the 365 heavens and their chief Archon, Abraxas, came to know the truth. This knowledge was then conveyed through the Hebdomad to Jesus, the son of Mary, who through his life and death redeemed the third "filiation" of the material world.

In this process yet another three-fold division is found: that which is material must return to the Chaos; that which is "psychic" to the Hebdomad; and that which is spiritual to the Not-Being God. When the third filiation is thus redeemed, the Supreme God pours out a blissful Ignorance over all that is. This is called "The Restoration of all things."

The Basilideans

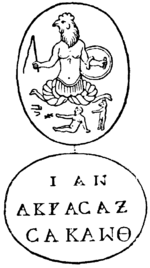

Because of Basilides' emphasis on the mystical Non-Being (oukon) of the utterly transcendent Deity, his followers came to be known as the Oukontiani. Reflecting their theology's emphasis on the threefold process of Restoration, the Basilideans had three gradesâmaterial, intellectual and spiritual. Members reportedly wore stones or gems cut in various symbolic forms, such as the heads of fowl and serpents. The Basilideans worshiped Abraxas as their supreme deity, and honored Jesus as the savior-teacher, in the Gnostic sense of revealing the special knowledge necessary for enlightenment.

According to Clement of Alexandria, faith was the foundation of the spiritual life of the Basilideans. However this faith it was not a submission of the intellect to the doctrines of the church, as in orthodox tradition. Rather, faith is a natural gift of understanding (gnosis) bestowed on the soul before its union with the body, which some possessed and others did not. Nevertheless, the Basilideans clearly sought to enlighten themselves through various spiritual exercises and study.

IrenĂŚus and Epiphanius reproached Basilides and his followers for immorality, and Jerome calls him a master and teacher of sexual debaucheries. However, these polemicists provide no direct evidence for these alleged moral crimes. On the other hand, Clement and Epiphanius did preserve a passage of the supposed writings of Basilides' son and successor, Isidore, which counsels the free satisfaction of sensual desires in order that the soul may find peace in prayer. Whether this writing is authentic or not is debated. Modern scholars tend to take the view that, while there may have been cases of licentiousness in both Orthodox Christian and Gnostic Christian circles, there is inadequate evidence to convict Basilides and his followers generally of this charge.

Legacy

Basilides' movement was apparently influential in the Christian movement of the second century, especially in Egypt. According to tradition, he was succeeded by his son Isidore. Basilides' ideas were also known in Rome and other parts of the empire, and the orthodox churches thus formed their official doctrines and creeds partly in reaction to the challenge posed by Basilides and other Gnostic teachers.

In the New Testament, the characterization of those who taught that Jesus did not come in the flesh as "antichrists" (2 John 1:7) may be connected to the teachings of Basilides. Similarly, the criticism leveled against Christians speculating about "myths and endless genealogies" (1 Timothy 1:4) is probably directed against Basilidean or similar Christian-Gnostic cosmologies.

In the Gnostic writings unearthed at Nag Hammadi in the mid-twentieth century can be found many cosmological ideas similar to those described as taught by Basilides. Several more specific parallels also exist. For example, the Second Treatise of the Great Seth confirms the fact that some Gnostic Christians believed it was Simon of Cyrene and not Jesus who actually died on the Cross. Here, Jesus says: "it was another, Simon, who bore the cross on his shoulder. It was another upon whom they placed the crown of thorns... And I was laughing at their ignorance."[1] In addition, the recently published Gospel of Judas takes a stance similar to that of the Basilideans in denigrating those Christians who believed that martyrdom brought them closer to Jesus.

Later Basilidean tradition combined with various other Egyptian ideas into a system of numerology based on the 365 days of the year and contemplation of the mystical name of Abraxas. The Non-Being God of Basilides also bears some resemblance to the Jewish kaballistic concept of Tzimtzum according to which God "contracted" his infinite light in a void, or "conceptual space," in which the finite world could exist. Etymologically, Abraxas may be related to the magical incantation Abracadabra.

More recently, the twentieth-century psychoanalyst Carl Jung attributed his Seven Sermons to the Dead to Basilides. The Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges was interested in Irenaeus' account of Basilides' doctrine and wrote an essay on the subject: "A Vindication of the False Basilides" (1932).

See also

Notes

- â Since much of Gnostic literature is allegorical, some believe that "Simon" here symbolizes the apparent physical body of Christ, rather than an actual person who substituted for him.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Attridge, Harold W., Charles W. Hedrick, and Robert Hodgson. Nag Hammadi, Gnosticism & Early Christianity. Peabody, Mass: Hendrickson Publishers, 1986. ISBN 978-0913573167

- Pearson, Birger A. Ancient Gnosticism: Traditions and Literature. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0800632588

- Procter, Everett. Christian Controversy in Alexandria: Clement's Polemic against the Basilideans and Valentinians. American university studies, v. 172. New York: P. Lang, 1995. ISBN 978-0820423784

- Roukema, Riemer. Gnosis and Faith in Early Christianity: An Introduction to Gnosticism. Harrisburg, Pa: Trinity Press International, 1999. ISBN 978-1563382994

- This article includes content derived from the Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge, 1914, which is in the public domain.

- This article is also based in part on the 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia, a publication now in the public domain.

External links

All links retrieved September 20, 2023.

- Fragments of Basilides â www.gnosis.org

- Fragments of his son Isidore â www.earlychristianwritings.com

- Catholic Encyclopedia on Basilides â www.newadvent.org

- Jung's Seven Sermons to the Dead â www.gnosis.org

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.