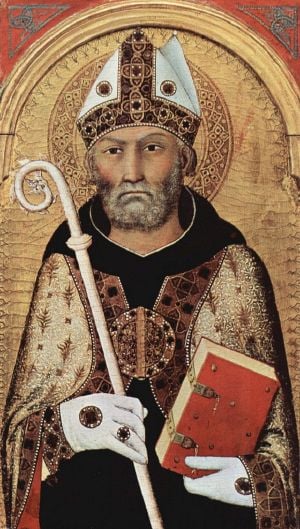

| Boniface I | |

|---|---|

| |

| Birth name | Unknown |

| Papacy began | December 28, 418 |

| Papacy ended | September 4, 422 |

| Predecessor | Zosimus |

| Successor | Celestine I |

| Born | Unknown |

| Died | September 4, 422 |

Pope Saint Boniface I was pope from December 28, 418 to September 4, 422. On the death of Pope Zosimus late in 418, two parties within the Roman church elected their own candidates for pope, one supporting the elderly priest Boniface, the other ordaining the archdeacon Eulalius. Boniface's opponent initially gained the upper hand, but Boniface had the support of the emperor's sister and other nobility. A church council ordered both "popes" to leave Rome until the matter was resolved, but at the following Easter, Eulalius returned to the city to celebrate the feast as pope. Imperial troops prevented this, Eulalius was stripped of his rank, and Boniface became the unchallenged pope soon thereafter.

As pope, Boniface re-established the papacy's opposition to Pelagianism, a teaching that had caused divisions within the African churches and had been strongly opposed by Saint Augustine. Boniface also persuaded Emperor Theodosius II to return Illyricum to western jurisdiction, and improved amicable relations with the European churches, which had felt constrained by the administrative policies of Pope Zosimus.

Background

Boniface would inherit three major problems as pope. First, his predecessor, Zozimus, had offended many European bishops by his heavy-handed dealing with their churches, in which he had establish a papal deputy in Arles, required all communications to the papacy to be screened by that city's metropolitan bishop. Second Zozimus had re-opened the Pelagian controversy over the role of grace and free will in salvation. Although Zozimus was forced eventually to reiterate the position of his predecessor, Innocent I, in condemning Pelagius, his handling of the the matter had allowed the churches to become disturbed over the matter again, especially in Africa. Third, and most importantly, Boniface faced opposition to his own election in the person of the "Antipope" Eulalius.

Biography

Boniface was the son of a presbyter (priest) and was a presbyter himself at Rome. He was already old and frail upon his elevation to the papacy. The Liber Pontificalis identifies his father as Jocundus. Boniface is believed to have been ordained as a priest by Pope Damasus I (366-384) and to have served as representative of Innocent I at Constantinople (c. 405) when the pope attempted to intervene on behalf of the recently-deposed bishop John Chrysostom.

Upon the death of Pope Zosimus, the Roman Church faced the disturbing spectacle of double papal elections. Just after Zosimus's funeral, on December 27, 418, a faction of the Roman clergy consisting principally of deacons seized the Lateran Basilica, the traditional place where new popes were elected, and chose Archdeacon Eulalius as pope. Little is known of the character and policies of Eulalius other than he seems to have been a willing candidate, while Boniface was not.

A non-theological issue in the controversy was clearly a division between the higher and lower clergy. Certain members of the higher clergyâpriests and bishops, some of who were of nobilityâtried to enter the building, but were repulsed by adherents of the Eulalian party. On the following day this group met in the Church of Theodora and elected as pope, reportedly against his will, the aged Boniface, well known for his charity, learning, and good character. On Sunday, December 29, both men were consecrated as pope, Boniface in the Basilica of St. Marcellus, and Eulalius in the Lateran Basilica. Boniface was supported by nine provincial bishops and some 70 priests, while those on Eulalius' side included numerous deacons, several priests and, significantly, the bishop of Ostia, who traditionally ordained the pope.

Each claimant immediately proceeded to act as pope in his own right, and Rome was thrown into tumult by the clash of the rival factions. The Roman prefect of Rome, Symmachus, was hostile to Boniface and reported the trouble to the (western) Emperor Honorius at Ravenna. Eulalius thus secured imperial confirmation of his election, and Boniface was expelled from the city. However, Boniface's supporters, including the emperor's sister, secured a hearing from Honorius, who then called a synod of Italian bishops at Ravenna. There, the churchmen were to meet both of the rival popes and resolve the matter. The council convened in February and March of 419 but was unable to reach a decision. A larger council of Italian, Gaulish, and African bishops was called to settle the issue. This synod ordered both claimants to leave Rome until a decision was reached and forbade their return under penalty of condemnation.

As Easter was approaching, Bishop Achilleus of Spoleto was deputed to conduct the paschal services in the vacant see of Rome. On March 18, however, Eulalius boldly returned to Rome and gathered his supporters, determined to preside over Easter services as pope. Spurning the prefect's orders to leave the city, he seized the Lateran Basilica on the Saturday before Easter and prepared to celebrate the resurrection of Christ. Imperial troops were dispatched to oust him from the church, and Achilleus ultimately conducted the services as planned.

The emperor was outraged at Eulalius' behavior and soon recognized Boniface as legitimate pope. Boniface re-entered Rome on April 10, and was popularly acclaimed.

Boniface set Rome on a more stable course in the Pelagian controversy and proved an able administrator. He gained concessions from the eastern emperor regarding Rome's ecclesiastical jurisdiction. He also improved relations with both the European and African churches. After an illness, on July 1, 420 Boniface requested the emperor to make some provision against possible renewal of the schism in the event of his death. Honorius enacted a law providing that, in contested papal elections, neither claimant should be recognized and a new election should be held.

The anti-pope Eulalius himself was not entirely discredited in the affair. He did not attempt to regain the papacy after Boniface's death, and he was subsequently appointed a bishop under Celestine I and died in 423. Boniface himself died on September 4, 422.

He was buried in the cemetery of Maximus on the Via Salaria, near the tomb of his favorite, Saint Felicitas, in whose honor he had erected an oratory over the cemetery bearing her name. The Roman Catholic Church keeps his feast on October 25.

Boniface's papacy

Boniface's reign was marked by great zeal and activity in disciplinary organization and control. He reversed his predecessor's policy of endowing certain western bishops, notably the metropolitan bishop of Arles, with extraordinary papal powers. Zosimus had given Bishop Patroclus of Arles extensive jurisdiction in the provinces of Vienna and Narbonne, and had made him the exclusive intermediary between these provinces and the Roman see. Boniface diminished these rights and restored the authority of the other chief bishops of these provinces.

Boniface inherited Pope Zosimus's difficulties with the African churches over the question of Pelagianism. Zosimus had reopened the Pelagian issue, which dealt with the question of the role of free will in human salvation. Pelagius held that humans were free to accept or reject God's grace and that Christians could perfect themselves through moral discipline. Bishop Augustine of Hippo took the lead in combating this view, arguing that God's grace is irresistible and that perfection in earthly life is impossible until the second advent of Christ. Under Zosimus' predecessor, Innocent I, it was decided that Pelagianism was heresy. Zosimus' decision to revisit the issue outraged Augustine and other African church leaders, who eventually forced Zozimus to uphold Innocent's original decision by publishing his own Tractoria condemning Pelagianism.

Boniface ardently supported Augustine in combating Pelagianism, persuading Emperor Honorius to issue an edict requiring all western bishops to adhere to Zosimus' Tractoria. Having received two Pelagian letters attacking Augustine, he forwarded these letters to the future saint. In recognition of this help, Augustine dedicated to Boniface his formal defense against the charges against him in his Contra duas Epistolas Pelagianoruin Libri quatuor.

In matters of church order, however, Augustine and Boniface were not always of one accord. In 422 Boniface received the appeal of Anthony of Fussula, who had been deposed by a provincial synod of Numidia through the efforts of Augustine. Affirming Rome's authority to intervene in the matter, Boniface decided that he should be restored if his innocence be established.

In his relations with the east, Boniface successfully maintained Roman jurisdiction over the ecclesiastical provinces of Illyricurn, after the patriarch of Constantinople attempted to establish his control over the area on account of their becoming a part of the Eastern empire. The bishop of Thessalonica had been constituted papal vicar in this territory, exercising jurisdiction over its metropolitans and lesser bishops. Boniface watched closely over the interests of the Illyrian church and insisted on its obedience to Rome rather than Constantinople. However, in 421, dissatisfaction was expressed by area bishops on account of the pope's refusal to confirm the election of a certain bishop in Corinth. The young (eastern) Emperor Theodosius II then granted the ecclesiastical dominion of Illyricurn to the patriarch of Constantinople (July 14, 421). Boniface prevailed upon Honorius to urge Theodosius to rescind his enactment. By a letter of March 11, 422, Boniface forbade the consecration in Illyricum of any bishop whom his deputy, Rufus, did not recognize.

Boniface also renewed the legislation of Pope Soter, prohibiting women to touch the sacred linens used during the mass or to minister at the burning of incense. He also enforced the laws forbidding slaves to become clerics.

Legacy

After a tumultuous beginning, Boniface I set the papacy on a stable course during the Pelagian controversy, affirmed Rome's leadership over the African and European churches, and resisted the encroachment of Constantinople over Roman jurisdiction in Illyricum.

On the other hand, the best known event of his papacy is certainly its first 15 weeks, when an apparent class struggle between the deacons of Rome and the higher clergy resulted in two rival popes being duly elected and ordained. This division within the Roman church was echoed in the struggle between Rome and Constantinople later in Boniface's papacy. Although his short reign as pope is remembered generally as a wise and effective one, it also served to remind the world how far the church had strayed from Jesus' commandment that his disciples "love one another," or saint Paul's hope that the church should be of "one accord" (Rom. 15:6).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Eno, Robert B. The Rise of the Papacy. Theology and life series, v. 32. Wilmington, Del: M. Glazier, 1990. ISBN 9780814658024

- Fortescue, Adrian. Early Papacy: To the Synod of Calcedon in 451. San Francisco: Ignatius, 2008. ISBN 9781586171766

- Loomis, Louise Ropes. The Book of the Popes: To the Pontificate of Gregory I. Merchantville N.J.: Evolution Pub, 2006. ISBN 9781889758862

- McBrien, Richard P. Lives of the Popes: The Pontiffs from St. Peter to John Paul II. San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1997. ISBN 9780060653040

- Maxwell-Stuart, P.G. Chronicle of the Popes: The reign-by-reign record of the papacy from St. Peter to the present. Thames and Hudson, 1997. ISBN 0500017980

| Roman Catholic Popes | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by: Zosimus |

Bishop of Rome 418â422 |

Succeeded by: Celestine I |

| |||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.