A concentration camp is a large detention center created for political opponents, specific ethnic or religious groups, civilians of a critical war-zone, or other groups of people, usually during a war. Inmates are selected according to some specific criteria, rather than individuals who are incarcerated after due process of law fairly applied by a judiciary. The most notorious concentration camps were the Nazi death camps, which were utilized to implement the Holocaust.

Ever since the Nazi concentration camps were discovered, the term has been understood to refer to a place of mistreatment, starvation, forced labor, and murder. Today, this term is used only in this extremely pejorative sense; no government or organization ever describes its own facilities as such—using instead terms such as "internment camp," "resettlement camp," "detention facility," and so forth—regardless of the actual circumstances of the camp, which can vary a great deal. In many cases, concentration camps had poor living conditions and resulted in many deaths, regardless of whether the camp was intended to kill its inhabitants.

In such a "concentration camp," a government can "concentrate" a group of people who are in some way undesirable in one place where they can be watched—for example, in a time of insurgency, potential supporters of the insurgents could be placed in such a facility where they cannot provide them with supplies or information. Concentration camps single out specific portions of a population based on their race, culture, politics or religion. Usually, these populations are not the majority but are seen as causing the social, economic, and other problems of the majority. The function of concentration camps are to separate the perceived problem, this "scapegoat" population, from the majority population. The very call for a population division labels the interned population, stigmatizing them.

Concentration camps have been used for centuries, but none have ever yielded positive results: The structure is based on the domination and subordination of smaller groups who hold limited social power. This kind of imposed dominance results in an immediate illusory solution to larger social woes, but creates cultural conflicts and rifts that may take generations to repair.

History

Early civilizations such as the Assyrians used forced resettlement of populations as a means of controlling territory, but it was not until much later that records exist of groups of civilians being concentrated into large prison camps. Polish historian Władysław Konopczyński has suggested the first such camps were created in Poland in the eighteenth century, during the Bar Confederation rebellion, when the Russian Empire established three camps for Polish rebel captives awaiting deportation to Siberia.[1] The term originated in the reconcentrados (reconcentration camps) set up by the Spanish military set up in Cuba during the Ten Years' War.

The English term "concentration camp" was first used to describe camps operated by the British in South Africa during the 1899-1902 Second Boer War. Allegedly conceived as a form of humanitarian aid to the families whose farms had been destroyed in the fighting, the camps were used to confine and control large numbers of civilians as part of a "Scorched Earth" tactic.

The term "concentration camp" was coined to signify the "concentration" of a large number of people in one place, and was used to describe both the camps in South Africa (1899-1902) and those established by the Spanish to support a similar anti-insurgency campaign in Cuba (c. 1895-1898),[2] although the original intention of these camps were markedly different.[3]

In the twentieth century, the arbitrary internment of civilians by the state became more common and reached a climax with Nazi concentration camps and the practice of genocide in extermination camps, and with the Gulag system of forced labor camps of the Soviet Union. As a result of this trend, the term "concentration camp" carries many of the connotations of "extermination camp." A concentration camp, however, is not by definition a death-camp. For example, many of the slave labor camps were used as cheap or free sources of factory labor for the manufacture of war materials and other goods.

As a result of mistreatment of civilians interned during conflicts, the Fourth Geneva Convention was established in 1949, to provide for the protection of civilians during times of war "in the hands" of an enemy and under any occupation by a foreign power.

Concentration camps around the world

Canada

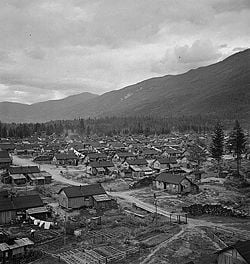

During World War I, and for two years after its end, thousands of foreign born men, women, and children were held in camps. This was part of the confinement of "enemy aliens" in Canada from 1914 to 1920, under the terms of the War Measures Act that would be used again in the Second World War. Of these, the majority of were not German or other "enemies" but actually Ukrainians and other East Europeans who had emigrated to Canada.[4]

There were twenty-four internment camps and related work sites.[5] Many of these internees were used for forced labor. Another 80,000 were registered as "enemy aliens" and obliged to regularly report to the police. In May 2008, following a lengthy effort spearheaded by the Ukrainian Canadian Civil Liberties Association, a redress settlement was achieved and the Canadian First World War Internment Recognition Fund was created.[6]

During World War II, Canada followed the U.S. in interning residents of Japanese and Italian ancestry. The Canadian government also interned citizens it deemed dangerous to national security. This included both fascists (including Canadians such as Adrien Arcand, who had negotiated with Hitler to obtain positions in the government of Canada once Canada was conquered), Montreal mayor Camilien Houde (for denouncing conscription) and union organizers and other people deemed to be dangerous Communists. Such internment was made legal by the Defence of Canada Regulations, Section 21 of which read:

The Minister of Justice, if satisfied that, with a view to preventing any particular person from acting in a manner prejudicial to the public safety or the safety of the State, it is necessary to do so, may, notwithstanding anything in these regulations, make an order […] directing that he be detained by virtue of an order made under this paragraph, be deemed to be in legal custody.

Over 75 percent were Canadian citizens who were vital in key areas of the economy, notably fishing, logging, and berry farming. Exile took two forms: Relocation centers for families and relatively well-off individuals who were a low security threat; and interment camps (often called concentration camps in contemporary accounts, but controversially so) which were for single men, the less well-off, and those deemed to be a security risk. After the war, many did not return to their home area because of bitter feelings as to their treatment, and fears of further hostility; of those that returned, only a few regained confiscated property and businesses. Most remained in other parts of Canada, notably certain parts of the interior of British Columbia and in the neighboring province of Alberta.

Germany

Prior to and during World War II, Nazi Germany maintained concentration camps (Konzentrationslager, abbreviated KZ or KL) throughout the territories it controlled. In these camps, millions of prisoners were killed through mistreatment, disease, starvation, and overwork, or were executed as unfit for labor. The Nazis adopted the term euphemistically from the British concentration camps of the Second Boer War in order to conceal the deadly nature of the camps.

Before the war, the Nazis were the only political party with paramilitary organizations at their disposal, the so-called SS and the SA, which had perpetrated surprise attacks on the offices and members of other parties throughout the 1920s. After the 1932 elections, it became clear to the Nazi leaders that they would never be able to secure a majority of the votes and that they would have to rely on other means to gain power. While gradually intensifying the acts of violence to wreak havoc among the opposition leading up to the 1933 elections, the Nazis set up concentration centers within Germany, many of which were established by local authorities, to hold, torture, or kill political prisoners and "undesirables" like outspoken journalists and communists. These early prisons—usually basements and storehouses—were eventually consolidated into full-blown, centrally run camps outside of the cities and somewhat removed from the public eye.

The first Nazi camps were set up inside Germany, and were set up to hold political opponents of the regime. The two principal groups of prisoners in the camps, both numbering in the millions, were Jews and Soviet and Polish prisoners of war (POWs). Large numbers of Roma (or Gypsies), Communists, and homosexuals, as well as some Jehovah's Witnesses and others were also sent to the camps. In addition, a small number of Western Allied POWs were sent to concentration camps for various reasons.[7] Western Allied POWs who were Jews, or whom the Nazis believed to be Jewish, were usually sent to ordinary POW camps; however, a small number were sent to concentration camps under anti-semitic policies.[8]

In 1938, the SS began to use the camps for forced labor at a profit. Many German companies used forced labor from these camps, especially during the subsequent war. Additionally, historians speculate that the Nazi regime utilized abandoned castles and similar existing structures to lock up the undesirable elements of society. The elderly, mentally ill, and handicapped were often confined in these makeshift camps where they were starved or gassed to death with diesel engine exhaust. The Final Solution was, thus, initially tested upon German citizens.

After 1939, with the beginning of the Second World War, concentration camps increasingly became places where the enemies of the Nazis were killed, enslaved, starved, and tortured. During the war, concentration camps for "undesirables" were spread throughout Europe. New camps were created near centers of dense "undesirable" populations, often focusing on areas with large Jewish, Polish intelligentsia, Communists, or Roma populations. Most of the camps were located in the area of General Government in occupied Poland for a simple logistical reason: Millions of Jews lived in Poland.

In most camps, prisoners were made to wear identifying overalls with colored badges according to their categorization: Red triangles for Communists and other political prisoners, green triangles for common criminals, pink for homosexual men, purple for Jehovah's Witnesses, black for Gypsies and asocials, and yellow for Jews.[9]

The transportation of prisoners was often carried out under horrifying conditions using rail freight cars, in which many died before they reached their destination. The prisoners were confined in these rail cars, often for days or weeks, without food or water. Many died in the intense heat of dehydration in summer or froze to death in the winter. Concentration camps for Jews and other "undesirables" also existed in Germany itself, and while not specifically designed for systematic extermination, many concentration camp prisoners died because of harsh conditions or were executed.

Starting in 1942, Nazi Germany established extermination or death camps for the sole purpose of carrying out the industrialized murder of the Jews of Europe—the "Final Solution." These camps were established in occupied Poland and Belarus, on the territory of the General Government. Over three million Jews would die in these extermination camps, primarily by poison gas, usually in gas chambers, although many prisoners were killed in mass shootings and by other means. These death camps, including Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka, and Auschwitz-Birkenau are commonly referred to as "concentration camps," but scholars of the Holocaust draw a distinction between concentration camps and death camps.

After 1942, many small subcamps were set up near factories to provide forced labor. IG Farben established a synthetic rubber plant in 1942, at Auschwitz III (Monowitz), and other camps were set up by airplane factories, coal mines, and rocket fuel factories. The conditions were brutal, and prisoners were often sent to the gas chambers or killed if they did not work fast enough.

Near the end of the war, the camps became sites for horrific medical experiments. Eugenics experiments, freezing prisoners to determine how exposure affected pilots, and experimental and lethal medicines were all tried at various camps.

Most of the Nazi concentration camps were destroyed after the war, though some were made into permanent memorials. Others, such as Sachsenhausen in the Soviet Occupation Zone, were used as NKVD special camps and were made subordinate to the Gulag before being finally closed in 1950. The remaining buildings and grounds at Sachsenhausen are now open to the public as a museum documenting its history in both the Nazi and Soviet eras.

Japan

Japan conquered south-east Asia in a series of victorious campaigns over a few months from December 1941. By March 1942, many civilians, particularly westerners in the region's European colonies, found themselves behind enemy lines and were subsequently interned by the Japanese.

The nature of civilian internment varied from region to region. Some civilians were interned soon after invasion; in other areas, the process occurred over many months. In total, approximately 130,000 Allied civilians were interned by the Japanese during this period of occupation. The exact number of internees will never be known, as records were often lost, destroyed, or simply not kept.

Civilians interned by the Japanese were treated marginally better than the prisoners of war, but their death rates were the same. Although they had to work to run their own camps, few were made to labor on construction projects. The Japanese devised no consistent policies or guidelines to regulate the treatment of the civilians. Camp conditions and the treatment of internees varied from camp to camp. The general experience, however, was one of malnutrition, disease, and varying degrees of harsh discipline and brutality from the Japanese guards.

The camps varied in size from four people held at Pangkalpinang in Sumatra to the 14,000 held in Tjihapit in Java. While some were segregated according to gender or race, there were also many camps of mixed gender. Some internees were held at the same camp for the duration of the war, and others were moved about. The buildings used to house internees were generally whatever was available, including schools, warehouses, universities, hospitals, and prisons.

One of the most famous concentration camps operated by the Japanese during World War II was at the University of Santo Tomas in Manila, the Philippines. The Dominican university was expropriated by the Japanese at the beginning of the occupation, and was used to house mostly American civilians, but also British subjects, for the duration of the war. There, men, women, and children suffered from malnutrition and poor sanitation. The camp was liberated in 1945.

The liberation of camps was not a uniform process. Many camps were liberated as the forces were recapturing territory. For other internees, freedom occurred many months after the surrender of the Japanese, and in the Dutch East Indies, liberated internees faced the uncertainty of the Indonesian war of independence.

North Korea

Concentration camps came into being in North Korea in the wake of the country's liberation from Japanese colonial rule at the end of World War II. Those persons considered "adversary class forces," such as landholders, Japanese collaborators, religious devotees, and families of those who migrated to the South, were rounded up and detained in a large facility. Additional camps were established later in earnest to incarcerate political victims in power struggles in the late 1950s and 1960s, and their families and overseas Koreans who migrated to the North. The number of camps saw a marked increase later in the course of cementing the Kim Il Sung dictatorship and the Kim Jong-il succession. About a dozen concentration camps were in operation until the early 1990s, the figure of which is believed to have been curtailed to five, due to increasing criticism of the North's perceived human rights abuses from the international community and the North's internal situation.

These five concentration camps are reported to have accommodated a total of over 200,000 prisoners, though the only one that has allowed outside access is Camp #15 in Yodok, South Hamgyong Province. Perhaps the most well-known depiction of life in the North Korean camps has been provided by Kang Chol-hwan in his memoir, The Aquariums of Pyongyang which describes how, once condemned as political criminals in North Korea the defendant and his or her family were incarcerated in one of the camps without trial and cut off from all outside contact. Prisoners reportedly worked 14 hour days at hard labor and/or ideological re-education. Starvation and disease were commonplace. Political criminals invariably received life sentences, however their families were usually released after 3 year sentences, if they passed political examinations after extensive study.[10]

People's Republic of China

Concentration camps in the People's Republic of China are called Laogai, which means "reform through labor." The communist-era camps began at least in the 1960s, and were filled with anyone who had said anything critical of the government, or often just random people grabbed from their homes to fill quotas. The entire society was organized into small groups in which loyalty to the government was enforced, so that anyone with dissident viewpoints was easily identifiable for enslavement. These camps were modern slave labor camps, organized like factories.

There have been accusations that Chinese labor camps products have been sold in foreign countries with the profits going to the PRC government.[11] These products include everything from green tea to industrial engines to coal dug from mines.

Poland

Following the First World War, concentration camps were erected for German civilian population in the areas that became part of Poland, including camps Szczypiorno and Stralkowo. In the camps, the inmates were abused and tortured.

After 1926, several other concentration camps were erected, not only for Germans, but also for Ukrainians and other minorities in Poland. These included camps Bereza-Kartuska and Brest-Litowsk. Official casualties for the camps are not known, however, it has been estimated that many Ukrainians died.

From the start of 1939 until the German invasion in September, a number of concentration camps for Germans, including Chodzen, were erected. Also, German population were subject to mass arrest and violent pogroms, which led to thousands of Germans fleeing. In 1,131 places in Poznan/Posen and Pomerania, German civilians were sent by marches to concentration camps. Infamous is the pogrom against Germans in Bydgoszcz/Bromberg, known to many Germans as Bromberger Blutsonntag.

Following the Second World War, the Soviet-installed Stalinist regime in Poland erected 1,255 concentrations camps for German civilians in the eastern parts of Germany that were occupied and annexed by Communist Poland. The inmates were mostly civilians that had not been able to flee the advancing Red Army or had not wanted to leave their homes. Often, entire villages including babies and small children were sent to the concentration camps, the only reason being that they spoke German. Some of them were also Polish citizens. Many anti-communists were also sent to concentration camps. Some of the most infamous concentration camps were Toszek/Tost, Lamsdorf, Potulice, and Świętochłowice/Schwientochlowitz. Inmates in the camps were abused, tortured, maltreated, exterminated, and deliberately given low food rations and epidemics were created. Some of the best known concentration camp commanders were Lola Potok, Czeslaw Geborski, and Salomon Morel. Several of them, including Morel, were Jewish Communists. Morel has been charged for war crimes and crimes against humanity by Poland.

The American Red Cross, U.S. Senator Langer of North Dakota, British ambassador Bentinck and British prime minister Winston Churchill protested against the Polish concentration camps, and demanded that the Communist authorities in Soviet-occupied Poland respected the Geneva Conventions and international law; however, international protests were ignored.

It is estimated that between 60,000 and 80,000 German civilians died in the Communist Polish concentration camps.

Russia and the Soviet Union

In Imperial Russia, labor camps were known under the name katorga. In the Soviet Union, concentration camps were called simply "camps," almost always plural (lagerya). These were used as forced labor camps, and were often filled with political prisoners. After Alexander Solzhenitsyn's book they have become known to the rest of the world as Gulags, after the branch of NKVD (state security service) that managed them. (In the Russian language, the term is used to denote the whole system, rather than individual camps.)

In addition to what is sometimes referred to as the GULAG proper (consisting of the "corrective labor camps") there were "corrective labor colonies," originally intended for prisoners with short sentences, and "special resettlements" of deported peasants.

There are records of reference to concentration camps by Soviet officials (including Lenin) as early as December 1917. While the primary purpose of Soviet camps was not mass extermination of prisoners, in many cases, the outcome was death or permanent disabilities. The total documentable deaths in the corrective-labor system from 1934 to 1953 amount to 1,054,000, including political and common prisoners; this does not include nearly 800,000 executions of "counterrevolutionaries" outside the camp system. From 1932 to 1940, at least 390,000 peasants died in places of peasant resettlement; this figure may overlap with the above, but, on the other hand, it does not include deaths outside the 1932-1940 period, or deaths among non-peasant internal exiles.

More than 14 million people passed through the Gulag from 1929 to 1953, with a further 6 to 7 million being deported and exiled to remote areas of the USSR.[12]

The death toll for this same time period at 1,258,537, with an estimated 1.6 million casualties from 1929 to 1953.[13] These estimates exclude those who died shortly after their release but whose death resulted from the harsh treatment in the camps, which was a common practice.[14]

After WWII, some 3,000,000 German soldiers and civilians were sent to Soviet labor camps, as part of war reparations by labor force. Only about 2,000,000 returned to Germany.

A special kind of forced labor, informally called sharashka, was for engineering and scientific labor. The famous Soviet rocket designer Sergey Korolev worked in a sharashka, as did Lev Termen and many other prominent Russians. Solzhenitsyn's book, The First Circle describes life in a sharashka.

United Kingdom

The term "concentration camp" was first used by the British military during the Boer War (1899-1902). Facing attacks by Boer guerrillas, British forces rounded up the Boer women and children as well as Africans living on Boer land, and sent them to 34 tented camps scattered around South Africa. This was done as part of a scorched earth policy to deny the Boer guerrillas access to the supplies of food and clothing they needed to continue the war.

Though they were not extermination camps, the women and children of Boer men who were still fighting were given smaller rations than others. The poor diet and inadequate hygiene led to endemic contagious diseases such as measles, typhoid, and dysentery. Coupled with a shortage of medical facilities, this led to large numbers of deaths—a report after the war concluded that 27,927 Boer (of whom 22,074 were children under 16) and 14,154 black Africans had died of starvation, disease, and exposure in the camps. In all, about 25 percent of the Boer inmates and 12 percent of the black African ones died (although further research has suggested that the black African deaths were underestimated and may have actually been around 20,000).

A delegate of the South African Women and Children's Distress Fund, Emily Hobhouse, did much to publicize the distress of the inmates on her return to Britain after visiting some of the camps in the Orange Free State. Her fifteen-page report caused uproar, and led to a government commission, the Fawcett Commission, visiting camps from August to December 1901, which confirmed her report. They were highly critical of the running of the camps and made numerous recommendations, for example, improvements in diet and provision of proper medical facilities. By February 1902, the annual death-rate dropped to 6.9 percent and eventually to 2 percent. Improvements made to the white camps were not as swiftly extended to the black camps. Hobhouse's pleas went mostly unheeded in the latter case.

During World War I, the British government interned male citizens of the Central Powers, principally Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Ottoman Turkey.[15]

During World War II, about 8,000 people were interned in the United Kingdom, many being held in camps at Knockaloe, close to Peel, and a smaller one near Douglas, Isle of Man. They included enemy aliens from the Axis Powers, principally Germany and Italy.[16]

Initially, refugees who had fled from Germany were also included, as were suspected British Nazi sympathizers, such as British Union of Fascists leader Oswald Mosley. The British government rounded up 74,000 German, Austrian and Italian aliens. However, within six months, the 112 alien tribunals had individually summoned and examined 64,000 aliens, and the vast majority were released, having been found to be "friendly aliens" (mostly Jews); examples include Hermann Bondi and Thomas Gold and members of the Amadeus Quartet. British nationals were detained under Defence Regulation 18B. Eventually, only 2,000 of the remainder were interned. Initially they were shipped overseas, but that was halted when a German U boat sank the SS Arandora Star in July 1940, with the loss of 800 internees, though this was not the first loss that had occurred. The last internees were released late in 1945, though many were released in 1942. In Britain, internees were housed in camps and prisons. Some camps had tents rather than buildings with internees sleeping directly on the ground. Men and women were separated and most contact with the outside world was denied. A number of prominent Britons including writer H.G. Wells campaigned against the internment of refugees.

One of the most famous example of modern "internment"—and one which made world headlines—occurred in Northern Ireland in 1971, when hundreds of nationalists and republicans were arrested by the British Army and the Royal Ulster Constabulary on the orders of the then Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, Brian Faulkner, with the backing of the British government. Historians generally view that period of internment as inflaming sectarian tensions in Northern Ireland while failing in its stated aim of arresting members of the paramilitary Provisional IRA, because many of the people arrested were completely unconnected with that organization but had had their names appear on the list of those to be interned through bungling and incompetence, and over 100 IRA men escaped arrest. The backlash against internment and its bungled application contributed to the decision of the British government under Prime Minister Edward Heath to suspend the Stormont governmental system in Northern Ireland and replace it with direct rule from London, under the authority of a British Secretary of State for Northern Ireland.

From 1971, internment began, beginning with the arrest of 342 suspected republican guerrillas and paramilitary members on August 9. They were held at HM Prison Maze. By 1972, 924 men were interned. Serious rioting ensued, and 23 people died in three days. The British government attempted to show some balance by arresting some loyalist paramilitaries later, but out of the 1,981 men interned, only 107 were loyalists. Internment was ended in 1975, but had resulted in increased support for the IRA and created political tensions which culminated in the 1981 Irish Hunger Strike and the death of Bobby Sands MP. The imprisonment of people under anti-terrorism laws specific to Northern Ireland continued until the Good Friday Agreement of 1998.

United States

The first large-scale confinement of a specific ethnic group in detention centers in the United States began in the summer of 1838, when President Martin Van Buren ordered the U.S. Army to enforce the Treaty of New Echota (an Indian Removal treaty) by rounding up the Cherokee into prison camps before relocating them. Called "emigration depots," the three main ones were located at Ross's Landing (Chattanooga, Tennessee), Fort Payne, Alabama, and Fort Cass (Charleston, Tennessee). Fort Cass was the largest, with over 4,800 Cherokee prisoners held over the summer of 1838.[17] Although these camps were not intended to be extermination camps, and there was no official policy to kill people, some Indians were raped and/or murdered by U.S. soldiers. Many more died in these camps due to disease, which spread rapidly because of the close quarters and bad sanitary conditions.

During World Wars I and II, many people deemed to be a threat due to enemy connections were interned in the U.S. This included people not born in the U.S. and also U.S. citizens of Japanese (in WWII), Italian (in WWII), and German ancestry. In particular, over 100,000 Japanese and Japanese Americans and Germans and German-Americans were sent to camps such as Manzanar during the Second World War. Those of Japanese ancestry were taken in reaction to the bombing of Pearl Harbor by Japan in 1941, United States Executive Order 9066, given on February 19, 1942, allowed military commanders to designate areas "from which any or all persons may be excluded." Under this order, all Japanese and Americans of Japanese ancestry were removed from Western coastal regions to guarded camps in Arkansas, Oregon, Washington, Wyoming, Colorado, and Arizona; German and Italian citizens, permanent residents, and American citizens of those respective ancestries (and American citizen family members) were removed from (among other places) the West and East Coast and relocated or interned, and roughly one-third of the U.S. was declared an exclusionary zone. Interestingly, Hawaii, despite a large Japanese population, did not use internment camps.

Some compensation for property losses was paid in 1948, and the U.S. government officially apologized for the internment in 1988, saying that it was based on "race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership," and paid reparations to former Japanese inmates who were still alive, while paying no reparations to interned Italians or Germans.

In the early twenty-first century, a detention center at Guantanamo Bay in Cuba was used to hold people suspected by the executive branch of the U.S. government of being al-Qaeda and Taliban operatives. The camp drew strong criticism both in the U.S. and world-wide for its detainment of prisoners without trial, and allegations of torture. The detainees held by the United States were classified as "enemy combatants." The U.S. administration had claimed that they were not entitled to the protections of the Geneva Conventions, but the U.S. Supreme Court ruled against this interpretation on June 29, 2006.[18] Following this, on July 7, 2006, the Department of Defense issued an internal memo stating that prisoners will in the future be entitled to protection under the Geneva Conventions.

Notes

- ↑ Władysław Konopczyński, Konfederacja barska, t. II (Warszawa, 1991), 733-734.

- ↑ Redfield Proctor, Cuban Reconcentration Policy and its Effects (March 17, 1898). Retrieved May 19, 2007.

- ↑ www.loc.gov, Reconcentration Policy. Retrieved May 19, 2007.

- ↑ Bohdan S. Kordan, Enemy Aliens, Prisoners of War: Internment in Canada During the Great War (McGill-Queen's University Press, 2003, ISBN 0773523502)

- ↑ Internment of Ukrainians in Canada 1914-1920, InfoUkes Inc. Retrieved September 30, 2010.

- ↑ Canadian First World War Internment Recognition Fund Retrieved September 30, 2010.

- ↑ Veterans Affair Canada, Prisoners of War in the Second World War. Retrieved May 19, 2007.

- ↑ Flint Whitlock, Given Up for Dead: American GIs in the Nazi Concentration Camp at Berga (Basic Books, 2005, ISBN 0813342880).

- ↑ Doris Bergen, Germany and the Camp System, PBS Radio Website. Retrieved March 15, 2007.

- ↑ Chol-hwan Kang and Pierre Rigoulot, The Aquariums of Pyongyang (Basic Books, 2005, ISBN 0465011047).

- ↑ Sam Lu, WOIPFG Report on Products Practitioners Are Forced Manufacture in China's Labor Camps, (Atlanta, Georgia 2003). Retrieved May 19, 2007.

- ↑ Robert Conquest, Victims of Stalinism: A Comment, Europe-Asia Studies 49(7) (Nov. 1997), 1317-1319.

- ↑ Steven Rosefielde, Red Holocaust (Routledge, 2009, ISBN 0415777577), 67, 77.

- ↑ Anne Applebaum, Gulag: A History (Doubleday, 2003, ISBN 0767900561), 583.

- ↑ Frances Coakley, Genealogy Pages Isle of Man—Internment (WW1 and WW2). Retrieved April 15, 2007.

- ↑ ScotsItalian.com, Alessandro Nardini, July 2006. Retrieved March 15, 2007.

- ↑ Barbara R. Duncan and Brett H. Riggs, Cherokee Heritage Trails Guidebook (University of North Carolina Press, 2003, ISBN 0807854573), 279.

- ↑ United States Supreme Court, Hamdan v. Rumsfeld. Retrieved February 10, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Applebaum, Anne. Gulag: A History. Doubleday, 2003. ISBN 0767900561

- Bergen, Doris. "Germany and the Camp System". PBS Radio Website, 2007. Retrieved March 31, 2007.

- Coakley, Frances. "Genealogy Pages Isle of Man—Internment (WW1 and WW2)." 2003. Retrieved April 30, 2007.

- Duncan, Barbara R., and Brett H. Riggs. Cherokee Heritage Trails Guidebook. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2003. ISBN 0807854573.

- Friedlander, Henry. The Origins of Nazi Genocide: From Euthanasia to the Final Solution. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1997. ISBN 0807846759.

- Kang, Chol-Hwan and Pierre Rigoulot. The Aquariums of Pyongyang: Ten Years in the North Korean Gulag. Basic Books, 2005. ISBN 0465011047.

- Kordan, Bohdan S. Enemy Aliens, Prisoners of War: Internment in Canada During the Great War. McGill-Queen's University Press, 2003. ISBN 0773523502

- Lu, Sam. "WOIPFG Report on Products Practitioners Are Forced Manufacture in China's Labor Camps." Atlanta, Georgia, 2003. Retrieved March 31, 2007.

- Nardini, Alessandro. ScotsItalian.com. 2006. Retrieved March 30, 2007.

- Repka, William and Kathleen. Dangerous Patriots: Canada's Unknown Prisoners of War. Vancouver: New Star Books, 1982. ISBN 0919573061.

- Rosefielde, Steven. Red Holocaust. Routledge, 2009. ISBN 0415777577

- Veterans Affair Canada. "Prisoners of War in the Second World War." Retrieved March 2007.

- Whitlock, Flint. Given Up for Dead: American GIs in the Nazi Concentration Camp at Berga. Basic Books, 2005. ISBN 0813342880.

External links

All links retrieved January 7, 2024.

- The Holocaust: Concentration Camps at Jewish Virtual Library.

- Concentration Camp System: In Depth at United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

- Information on the Japanese-American Internment Camp Manzanar

- Canadian First World War Internment Recognition Fund

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Internment history

- List_of_concentration_and_internment_camps history

- Nazi_concentration_camps history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.