An entrepreneur (a loanword from French introduced and first defined by the Irish economist Richard Cantillon) is a person who undertakes and operates a new enterprise or venture and assumes some accountability for the inherent risks involved. In the context of the creation of for-profit enterprises, entrepreneur is often synonymous with "founder." Most commonly, the term entrepreneur applies to someone who establishes a new entity to offer a new or existing product or service into a new or existing market, whether for a profit or not-for-profit outcome.

Business entrepreneurs often have strong beliefs about a market opportunity and are willing to accept a high level of personal, professional, or financial risk to pursue that opportunity. Business entrepreneurs are often highly regarded in U.S. culture as critical components of its capitalistic society. In this light, differences among rates of growth and technical progress has been attributed to the quality of entrepreneurship in various countries. The willingness to take responsibility for the inherent risk of innovation is thus seen as a necessary component of a society's development of the material aspects of a more comfortable, happy life for its members.

Characteristics of an Entrepreneur

An entrepreneur is a person who organizes and manages any enterprise, especially a business, usually with considerable initiative and risk. They may be an employer of productive labor, or may (especially initially) work alone.

Organizer

An entrepreneur is one who combines the land of one, labor of another, and the capital of yet another, and, thus, produces a product. By selling the product in the market, he pays interest on capital, rent on land, and wages to laborers, and what remains is his or her profit.

Leader

Reich (1987) considered leadership, management ability, and team-building as essential qualities of an entrepreneur. This concept has its origins in the work of Richard Cantillon in his Essai sur la Nature du Commerce en Général (1755) and Jean-Baptiste Say's (1803) Treatise on Political Economy.

Entrepreneur is sometimes mistakenly equated with "opportunist." An entrepreneur may be considered one who creates an opportunity rather than merely exploits it, though that distinction is difficult to make precise. Joseph Schumpeter (1989) and William Baumol (2004) have considered more opportunistic behavior such as arbitrage one role of the entrepreneur, as this helps to generate innovation or mobilize resources to address inefficiencies in the marketplace.

Risk Bearer

An entrepreneur is an agent who buys factors of production at certain prices in order to combine them into a product with a view to selling it at uncertain prices in the future. Uncertainty is defined as a risk, which cannot be insured against and is incalculable. There is a distinction between ordinary risk and uncertainty. A risk can be reduced through the insurance principle, where the distribution of the outcome in a group of instances is known. On the contrary, uncertainty is a risk which cannot be calculated.

The entrepreneur, according to Knight (1967), is the economic functionary who undertakes such responsibility of uncertainty, which by its very nature cannot be insured, or capitalized, or salaried to. Casson (2003) has extended this notion to characterize entrepreneurs as decision makers who improvise solutions to problems which cannot be solved by routine alone.

Personality Characteristics

Burch (1986) listed traits typical of entrepreneurs:

- A desire to achieve: The push to conquer problems, and give birth to a successful venture.

- Hard work: It is often suggested that many entrepreneurs are "workaholics."

- Desire to work for themselves: Entrepreneurs like to work for themselves rather than working for an organization or any other individual. They may work for someone to gain knowledge of the product or service that they may want to produce.

- Nurturing quality: Willing to take charge of, and watch over a venture until it can stand alone.

- Acceptance of responsibility: Are morally, legally, and mentally accountable for their ventures. Some entrepreneurs may be driven more by altruism than by self-interest.

- Reward orientation: Desire to achieve, work hard, and take responsibility, but also with a commensurate desire to be rewarded handsomely for their efforts; rewards can be in forms other than money, such as recognition and respect.

- Optimism: Live by the philosophy that this is the best of times, and that anything is possible.

- Orientation to excellence: Often desire to achieve something outstanding that they can be proud of.

- Organization: Are good at bringing together the components (including people) of a venture.

- Profit orientation: Want to make a profit—but the profit serves primarily as a meter to gauge their success and achievement.

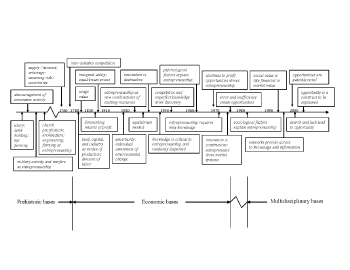

Theories of Entrepreneurship

Sociologist Max Weber saw entrepreneurial efforts as the result of the Protestant "work ethic," which was the idea that people sought to prove their value before God through hard work. This proof took the form of pursuing the greatest works possible on earth, inevitably through industry, with the profits made by entrepreneurs regarded as their moral affirmation.

Generally, business scholars have two classes of theories of how people become entrepreneurs, called supply and demand theories, after economic theory.

On the supply-side, research studies have shown that entrepreneurs are convinced that they can command their own destinies. Behavioral scientists express this by saying that entrepreneurs perceive the "locus of control" to be within themselves. It is this self-belief which stimulates the entrepreneur, according to supply-side theorists.

A more generally held theory is that entrepreneurs emerge from the population on demand, from the combination of opportunities and people well-positioned to take advantage of them. In the demand theory, anyone could be recruited by circumstance or opportunity to become an entrepreneur. The entrepreneur may perceive that they are among the few to recognize or be able to solve a problem. In this view, one studies on one side the distribution of information available to would-be entrepreneurs (see Austrian School economics) and on the other, how environmental factors (access to capital, competition, and so forth) change the rate of a society's production of entrepreneurs. Richard Cantillon was known for his demand theory of entrepreneurship in which he said production depends on the demand of land owners who contract out their work. Those who undertake the work demanded are entrepreneurs and they are responsible for resource allocation within a society and bring prices into line with demand. Jean-Baptiste Say also emphasized the importance of entrepreneurs, to the point of considering them as the fourth factor of production (behind land, capital, and labor). Say called entrepreneurs "forecasters, project appraisers, and risk-takers." Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk suggested that entrepreneurs bring about structural changes as their efforts are guided by changes in the relative prices of capital goods.

Another early economic theory of entrepreneurship and its relationship to capitalism was proposed by Francis Amasa Walker (1888), who saw profits as the "wages" for successful entrepreneurial work.

The understanding of entrepreneurship owes a lot to the work of economist Joseph Schumpeter. Schumpeter (1950) described an entrepreneur as a person who is willing and able to convert a new idea or invention into a successful innovation. Entrepreneurship forces "creative destruction" across markets and industries, simultaneously creating new products and business models others. In this way, creative destruction is largely responsible for the dynamism of industries and long-run economic growth.

The place of the disharmony-creating and idiosyncratic entrepreneur in traditional economic theory (which describes many efficiency-based ratios assuming uniform outputs) presents theoretic quandaries. Thus, despite Schumpeter's early twentieth-century contributions, the traditional microeconomic theories of economics have had little room for entrepreneurs in their theoretical frameworks (instead assuming that resources would find each other through a price system). Entrepreneurship today, however, is widely regarded as an integral player in the business culture of American life, and particularly as an engine for job creation and economic growth. Robert Sobel (2000) and William Baumol (2004) have added greatly to this area of economic theory.

For Frank H. Knight (1967) and Peter Drucker (1970) entrepreneurship is about taking risk. The behavior of the entrepreneur reflects a kind of person willing to put his or her career and financial security on the line and take risks in the name of an idea, spending much time as well as capital on an uncertain venture.

History of Entrepreneurial Activity

Entrepreneurship is the practice of starting new organizations, particularly new businesses, generally in response to identified opportunities. Entrepreneurship is often a difficult undertaking, as the majority of new businesses fail. Entrepreneurial activities are substantially different depending on the type of organization that is being started, ranging in scale from solo projects (even involving the entrepreneur only part-time) to major undertakings creating many job opportunities.

Entrepreneurship received a boost in the formalized creation of so-called incubators and science parks (such as those listed at National Business Incubation Association) where businesses can start on a small scale, share services and space while they grow, and eventually move into space of their own when they have achieved a large enough scale to be viable stand-alone businesses. Also, entrepreneurship is being employed to revitalize fading downtowns and inner cities, which may have excellent resources but suffer from a lack of spirited development.

Famous Entrepreneurs

Famous American entrepreneurs include:

- Jeff Bezos (retail)

- Sergey Brin (search engines)

- Andrew Carnegie (steel)

- Tom Carvel (ice cream and was the first person to use franchising as a business model)

- Ben Cohen (ice cream)

- Barron Collier (advertising)

- Michael Dell (computer retail)

- George Eastman (photography)

- Thomas Edison (electro-mechanics)

- Larry Ellison (database systems)

- Henry Ford (automobiles)

- Christopher Gardner (stock brokerage)

- Bill Gates (software)

- Sylvan Goldman (shopping carts)

- Jerry Greenfield (ice cream)

- Reed Hastings (online DVD rentals)

- Milton S. Hershey (confections)

- Steve Jobs (computer hardware, software)

- Scott A. Jones (voicemail, search engine)

- Ray Kroc (fast food restaurants)

- Estee Lauder (cosmetics)

- J. Pierpont Morgan (banking)

- Elisha Otis (elevators)

- Larry Page (search engines)

- John D. Rockefeller (oil)

- Howard Schultz (coffee franchise)

- Li Ka Shing (manufacturing and telecommunications turned conglomerate)

- Elmer Sperry (avionics)

- Donald Trump (real estate)

- Ted Turner (media)

- Sam Walton (department stores)

- Thomas J. Watson Sr. (computers)

Famous Australian entrepreneurs include Gerry Harvey (auction house turned to homewares and electronics retailer), Frank Lowy (shopping center real estate), and Dick Smith (electronics).

Famous British entrepreneurs include Richard Branson (travel and media), James Dyson (home appliances), and Alan Sugar (computers).

Famous French entrepreneurs include Bernard Arnault and Francis Bouygues.

Famous German entrepreneurs include Werner von Siemens and Ferdinand von Zeppelin.

Famous Greek entrepreneurs include Stelios Haji-Ioannou.

Famous Swedish entrepreneurs include Ingvar Kamprad (home furnishing).

Famous Indian entrepreneurs include Vinod Khosla, Kanwal Rekhi and many more who contributed to Silicon Valley's entrepreneur revolution. Dhirubhai Ambani, Narayana Murthy, Azim Premji, and many more contributed to the Indian entrepreneur revolution.

Famous Japanese entrepreneurs include Konosuke Matsushita, Soichiro Honda, Akio Morita, Eiji Toyoda.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Baumol, William J. 2004. The Free-Market Innovation Machine: Analyzing the Growth Miracle of Capitalism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 069111630X

- Bird, B. 1992. "The Roman God Mercury: An Entrepreneurial Archetype" Journal of Management Enquiry 1(3).

- Burch, John G. 1986. "Profiling the Entrepreneur" in Business Horizons 29(5):13-16.

- Busenitz, L. and J. Barney. 1997. "Differences between entrepreneurs and managers in large organizations" Journal of Business Venturing 12.

- Cantillon, Richard. 1759. "Essai sur la Nature du Commerce in Général". The Library of Economics and Liberty. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- Casson, M. 2003. The Entrepreneur: An Economic Theory (2nd edition). Edward Elgar Publishing. ISBN 1845421930

- Cole, A. 1959. Business Enterprise in its Social Setting. Harvard University Press.

- Collins, J. and D. Moore. 1970. The Organization Makers. Appleton-Century-Crofts.

- Drucker, Peter. 1970. "Entrepreneurship in Business Enterprise" Journal of Business Policy 1.

- Florida, R. 2002. The Rise of the Creative Class: And How It's Transforming Work, Leisure, Community and Everyday Life. Perseus Books Group.

- Folsom, Burton W. 1987. The Myth of the Robber Barons. Young America. ISBN 0963020315

- Hebert, R.F., and A.N. Link. 1988. The Entrepreneur: Mainstream Views and Radical Critiques (2nd edition). New York: Praeger. ISBN 0275928101

- Knight, K. 1967. "A descriptive model of the intra-firm innovation process" Journal of Business of the University of Chicago 40.

- McClelland, D. 1961. The Achieving Society. Princeton. NJ: Van Nostrand. ISBN 0029205107

- Murphy, P.J., J. Liao, and H.P. Welsch. 2006. "A conceptual history of entrepreneurial thought" Journal of Management History 12(1): 12-35.

- Pinchot, G. 1985. Intrapreneuring. New York, NY: Harper and Row.

- Reich, R.B. 1987. "Entrepreneurship reconsidered: The team as hero" Harvard Business Review.

- Schumpeter, Joseph A. 1950. Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy (3rd edition). New York, NY: Harper and Row. ISBN 0415107628

- Schumpeter, Joseph A. 1989. Essays: On Entrepreneurs, Innovations, Business Cycles, and the Evolution of Capitalism. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 0887387640

- Shane S. 2003. "A general theory of entrepreneurship: the individual-opportunity nexus" New Horizons in Entrepreneurship series. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Sobel, Robert. 2000. The Entrepreneurs: Explorations Within the American Business Tradition. Beard Books. ISBN 1587980274

- Walker, Francis Amasa. 1888. Political Economy (3rd edition). Macmillan and Co.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.