| Quagga | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Quagga in London Zoo, 1870

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| †Equus quagga quagga Boddaert, 1785 |

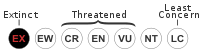

Quagga is an extinct subspecies, Equus quagga quagga, of the plains zebra or common zebra (E. quagga), characterized by the vivid, dark stripes located only on the head, neck, and shoulders, with the stripes fading and more spread apart on the mid-section and the posterior area a plain brown. The quagga once was considered a separate species, E. quagga and the plains zebra was classified as E. burchelli. The quagga was the first extinct animal to have its DNA studied and it was such genetic analysis that indicated the quagga was a subspecies of the plains zebra.

The quagga once was found in great numbers in South Africa, but has been extinct since the end of the nineteenth century, with the last individual dying in 1883 in the Amsterdam Zoo. The reasons for the demise of the quagga are attributed to anthropogenic factors: Over hunting and competition with domestic livestock. Now human beings are trying to recreate animals with similar markings using selective breeding of particular plains zebras.

Overview and description

The quagga (Equus quagga quagga) is a member of the Equidae, a family of odd-toed ungulate mammals of horses and horse-like animals. There are three basic groups recognized in Equidae‚ÄĒhorses, asses, and zebras‚ÄĒalthough all extant equids are in the same genus of Equus.

Zebras are wild members of the genus Equus, native to eastern and southern Africa and characterized by distinctive white and black (or brown) stripes that come in different patterns unique to each individual. The quagga is now recognized as an extinct subspecies of one of the three or four extant species of zebras, the plains zebra (E. quagga), which is also known as the common zebra, the painted zebra, and Burchell's zebra. The other extant species are Grévy's zebra (E. grevyi), the Cape mountain zebra (Equus zebra), and the Hartmann's mountain zebra (E. hartmannae), although the Cape mountain zebra and Hartmann's mountain zebra are sometimes treated as the same species. The plains zebra, Cape mountain zebra, and Hartmann's mountain zebra are similar and placed in the same subgenus of Hippotigris. Grévy's zebra is placed in its own subgenus of Dolichohippus.

The quagga was distinguished from other zebras by having the usual vivid black marks on the front part of the body only. In the mid-section, the stripes faded and the dark, inter-stripe spaces became wider, and the rear parts were a plain brown. Overall, the coat was sandy brown and the tail white.

The name quagga comes from a Khoikhoi word for zebra and is onomatopoeic, being said to resemble the quagga's call. The only quagga to have ever been photographed alive was a mare at the Zoological Society of London's Zoo in Regent's Park in 1870.

Range, habitat, and extinction

The Quagga once was found in great numbers in South Africa in the former Cape Province (now known as the Cape of Good Hope Province) and the southern part of the Orange Free State. It lived in the drier parts of South Africa, on grassy plains. The northern limit seems to have been the Orange River in the west and the Vaal River in the east; the south-eastern border may have been the Great Kei River.

The quagga was hunted to extinction for meat, hides, and to preserve feed for domesticated stock. The last wild quagga was probably shot in the late 1870s, and the last specimen in captivity, a mare, died on August 12, 1883, at the Artis Magistra zoo in Amsterdam.

Taxonomy

The quagga was originally classified as an individual species, Equus quagga, in 1778. Over the next fifty years or so, many other zebras were described by naturalists and explorers. Because of the great variation in coat patterns (no two zebras are alike), taxonomists were left with a great number of described "species," and no easy way to tell which of these were true species, which were subspecies, and which were simply natural variants.

Long before this confusion was sorted out, the quagga became extinct. Because of the great confusion between different zebra species, particularly among the general public, the quagga had become extinct before it was realized that it appeared to be a separate species.

The quagga was the first extinct creature to have its DNA studied. Recent genetic research at the Smithsonian Institution indicated that the quagga was in fact not a separate species at all, but diverged from the extremely variable plains zebra, Equus burchelli, between 120,000 and 290,000 years ago, and suggests that it should be named Equus burchelli quagga. However, according to the rules of biological nomenclature, where there are two or more alternative names for a single species, the name first used takes priority. As the quagga was described about thirty years earlier than the plains zebra, it appears that the correct terms are E. quagga quagga for the quagga and E. quagga burchelli for the plains zebra, unless "Equus burchelli" is officially declared to be a nomen conservandum.

After the very close relationship between the quagga and surviving zebras was discovered, the Quagga Project was started by Reinhold Rau in South Africa to recreate the quagga by selective breeding from plains zebra stock, with the eventual aim of reintroducing them to the wild. This type of breeding is also called breeding back. In early 2006, it was reported that the third and fourth generations of the project have produced animals that look very much like the depictions and preserved specimens of the quagga, though whether looks alone are enough to declare that this project has produced a true "re-creation" of the original quagga is controversial.

DNA from mounted specimens was successfully extracted in 1984, but the technology to use recovered DNA for breeding does not yet exist. In addition to skins such as the one held by the Natural History Museum in London, there are 23 known stuffed and mounted quagga throughout the world. A twenty-fourth specimen was destroyed in Königsberg, Germany (now Kaliningrad), during World War II (Max 2006).

Quagga hybrids and similar animals

Zebras have been cross-bred to other equines such as donkeys and horses. There are modern animal farms tht continue to do so. The offspring are known as zeedonks, zonkeys, and zorses (the term for all such zebra hybrids is zebroid). Zebroids are often exhibited as curiosities although some are broken to harness or as riding animals. On January 20, 2005, Henry, a foal of the Quagga Project, was born. He most resembles the quagga.

There is a record of a quagga bred to a horse in the 1896 work, Anomalies and Curiosities of Medicine, by George M. Gould and Walter L. Pyle (Hartwell): "In the year 1815 Lord Morton put a male quagga to a young chestnut mare of seven-eighths Arabian blood, which had never before been bred from. The result was a female hybrid which resembled both parents.""

In his 1859 The Origin of Species, Charles Darwin recalls seeing colored drawings of zebra-donkey hybrids, and mentions, "Lord Moreton's famous hybrid from a chesnut [sic] mare and male quagga…" Darwin mentioned this particular hybrid again in 1868 in The Variation Of Animals And Plants Under Domestication (Darwin 1883), and provides a citation to the journal in which Lord Morton first described the breeding.

Okapi markings are nearly the reverse of the quagga, with the forequarters being mostly plain and the hindquarters being heavily striped. However, the okapi is no relation of the quagga, horse, donkey, or zebra. Its closest taxonomic relative is the giraffe.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Darwin, C. 1883. The Variation of Animals and Plants Under Domestication, 2nd edition, revised. New York: D. Appleton & Co. Retrieved February 8, 2009.

- Hack, M. A, and E. Lorenzen. 2008. Equus quagga. In IUCN, IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved February 8, 2009.

- Hack, M. A., R. East, and D. I. Rubenstein. 2008. Equus quagga ssp. quagga. In IUCN, 2008 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved February 8, 2009.

- Hartwell, S. n.d. Hybrid equines. Messybeast.com. Retrieved February 8, 2009.

- Max D.T. 2006. Can you revive an extinct animal? New York Times January 1, 2006.

External links

All links retrieved December 6, 2022.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.