| Part of a series of articles on Freemasonry | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

|

Core Articles Freemasonry · Grand Lodge · Masonic Lodge · Masonic Lodge Officers · Prince Hall Freemasonry · Regular Masonic jurisdictions History History of Freemasonry · Liberté chérie · Masonic manuscripts

| |||||||||||||

Freemasonry is a fraternal organization that arose from obscure origins in the late sixteenth to early seventeenth century. Freemasonry now exists in various forms all over the world, with a membership estimated at around six million, with around 480,000 in England, Scotland and Ireland alone, and over two million in the United States. The various forms all share moral and metaphysical ideals, which include, in most cases, a constitutional declaration of belief in a Supreme Being.

The fraternity is administratively organized into Grand Lodges (or sometimes Orients). Each governs its own jurisdiction, which includes subordinate or constituent Lodges. Grand Lodges recognize each other through a process of landmarks and regularity. There are also appendant bodies, organizations related to the main branch of Freemasonry, but with their own independent administration.

Freemasonry uses the metaphors of operative stonemasons' tools and implements, against the allegorical backdrop of the building of King Solomon's Temple, to convey what has been described by both Masons and critics as "a system of morality veiled in allegory and illustrated by symbols."

When the Lodges were founded they were early examples of self-governing institutions that encouraged social responsibility and respect for the law. It was in such Lodges, at the time called secret societies, that many people learned the basic ideas of democracy. Many Freemasons were involved in promoting equality and democracy in their countries and, as individuals, were often leaders in the revolutions in United States, France, Italy, Russia and other countries.

History

The origins and early development of Freemasonry are a matter of some debate and conjecture. There is some evidence to suggest that there were Masonic Lodges in existence in Scotland as early as the late sixteenth century,[1] and clear references to their existence in England by the mid seventeenth century.[2] A poem known as "The Regius Manuscript" has been dated to approximately 1390 and is the oldest known Masonic text.[3]

The first Grand Lodge, the Grand Lodge of England (GLE), was founded on June 24, 1717, when four existing London Lodges met for a joint dinner. This rapidly expanded into a regulatory body, which most English Lodges joined. However, a few lodges resented some of the modernizations that GLE endorsed, such as the creation of the Third Degree, and formed a rival Grand Lodge on July 17, 1751, which they called the "Antient Grand Lodge of England." The two competing Grand Lodges vied for supremacy—the "Moderns" (GLE) and the "Ancients" (or "Antients")—until they united 25 November 1813 to form the United Grand Lodge of England (UGLE).

The Grand Lodges of Ireland and Scotland were formed in 1725 and 1736 respectively. Freemasonry was exported to the British Colonies in North America by the 1730s–with both the "Ancients" and the "Moderns" (as well as the Grand Lodges of Ireland and Scotland) chartering offspring ("daughter") Lodges, and organizing various Provincial Grand Lodges. After the American Revolution, independent U.S. Grand Lodges formed themselves within each State. Some thought was briefly given to organizing an over-arching "Grand Lodge of the United States," with George Washington (who was a member of a Virginian lodge) as the first Grand Master, but the idea was short-lived. The various State Grand Lodges did not wish to diminish their own authority by agreeing to such a body.[4]

Although there are no real differences in the Freemasonry practiced by lodges chartered by the Ancients or the Moderns, the remnants of this division can still be seen in the names of most Lodges, F.& A.M. signifying Free and Accepted Masons and A.F.& A.M. signifying Antient Free and Accepted Masons.

The oldest jurisdiction on the continent of Europe, the Grand Orient de France (GOdF), was founded in 1728. However, most English-speaking jurisdictions cut formal relations with the GOdF around 1877 when the GOdF removed the requirement that its members have a belief in a Deity (thereby accepting atheists).[5] The Grande Loge Nationale Française (GLNF)[6] is currently the only French Grand Lodge that is in regular amity with the UGLE and its many concordant jurisdictions worldwide.

Due to the above history, Freemasonry is often said to consist of two branches not in mutual regular amity:

- the UGLE and concordant tradition of jurisdictions (termed Grand Lodges) in amity, and

- the GOdF, European Continental, tradition of jurisdictions (often termed Grand Orients) in amity.

In most Latin countries, the GOdF-style of European Continental Freemasonry predominates, although in most of these Latin countries there are also Grand Lodges that are in regular amity with the UGLE and the worldwide community of Grand Lodges that share regular "fraternal relations" with the UGLE. The rest of the world, accounting for the bulk of Freemasonry, tends to follow more closely to the UGLE style, although minor variations exist.

Organizational structure

Grand Lodges and Grand Orients are independent and sovereign bodies that govern Masonry in a given country, state, or geographical area (termed a jurisdiction). There is no single overarching governing body that presides over world-wide Freemasonry; connections between different jurisdictions depend solely on mutual recognition.

Regularity

Regularity is a constitutional mechanism whereby Grand Lodges or Grand Orients give one another mutual recognition. This recognition allows formal interaction at the Grand Lodge level, and gives individual Freemasons the opportunity to attend Lodge meetings in other recognized jurisdictions. Conversely, regularity proscribes interaction with Lodges that are irregular. A Mason who visits an irregular Lodge may have his membership suspended for a time, or he may be expelled. For this reason, all Grand Lodges maintain lists of other jurisdictions and lodges they consider regular:

The solution of the problem [of irregular Masonry] lies in the publication furnished every California lodge. Entitled "List of Regular Lodges Masonic," it is issued by the Grand Lodge of California to its constituent lodges, with the admonition that this book is to be kept in each lodge for reference in receiving visitors and on applications for affiliation. There may well be an old copy which you can use, for it is re-issued every year.[7]

Grand Lodges and Grand Orients that afford mutual recognition and allow intervisitation are said to be in amity. As far as the UGLE is concerned, regularity is predicated upon a number of landmarks, set down in the UGLE Constitution and the Constitutions of those Grand Lodges with which they are in amity. Even within this definition there are some variations with the quantity and content of the Landmarks from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. Other Masonic groups organize differently.

Each of the two major branches of Freemasonry considers the Lodges within its branch to be "regular" and those in the other branch to be "irregular." As the UGLE branch is significantly larger, however, the various Grand Lodges and Grand Orients in amity with UGLE are commonly referred to as "regular" (or "Mainstream") Masonry, while those Grand Lodges and Grand Orients in amity with GOdF are commonly referred to "liberal" or "irregular" Masonry. (The issue is complicated by the fact that the usage of "Lodge" versus "Orient" alone is not an indicator of which branch a body belongs to, and thus not an indication of regularity). The term "irregular" is also universally applied to various self created bodies that call themselves "Masonic" but are not recognized by either of the main branches.

Masonic Lodge

A Lodge (often termed a Private Lodge or Constituent Lodge in Masonic constitutions) is the basic organizational unit of Freemasonry. Every Lodge must be issued a Warrant or Charter by a Grand Lodge, authorizing it to work. Lodges that meet without such authorization are deemed "Clandestine" and irregular. A Lodge must hold full meetings regularly at published dates and places. It will elect, initiate and promote its own members and officers; it will own, occupy or share premises; and will normally build up a collection of minutes, records and equipment. Like any other organization, it will have formal business, annual general meetings (AGMs), charity funds, committees, reports, bank accounts and tax returns, and so forth.

A man can only be initiated, or made a Mason, in a Lodge, of which he may well remain a subscribing member for life. A Master Mason is generally entitled to visit any Lodge meeting under any jurisdiction in amity with his own, and a Lodge may well offer hospitality to such a visitor after the formal meeting. He is first usually required to check the regularity of that Lodge, and must be able to satisfy that Lodge of his own regularity; and he may be refused admission if adjudged likely to disrupt the harmony of the Lodge. If he wishes to visit the same Lodge repeatedly, he may be expected to join it, and pay a membership subscription.

Freemasons correctly meet as a Lodge, not in a Lodge, the word "Lodge" referring more to the people assembled than the place of assembly. However, in common usage, Masonic premises are often referred to as "Lodges." Masonic buildings are also sometimes called "Temples" ("of Philosophy and the Arts"). In many countries, Masonic Center or Hall has replaced Temple to avoid arousing prejudice and suspicion. Several different Lodges, as well as other Masonic organizations, often use the same premises at different times.

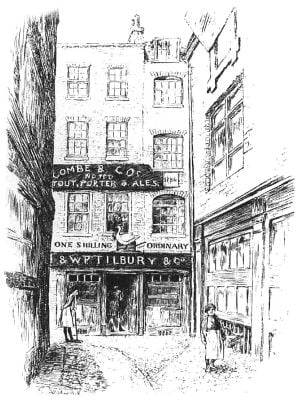

Early Lodges often met in a tavern or any other convenient fixed place with a private room.[5] According to Masonic tradition, the Lodge of medieval stonemasons was on the southern side of the building site, with the sun warming the stones during the day. The social Festive Board (or Social Board), part of the meeting is thus sometimes called the South: " …but when [the sun] reaches the south, the hour is high twelve, and we are summoned to refreshment."[8]

Most Lodges consist of Freemasons living or working within a given town or neighborhood. Other Lodges are composed of Masons with a particular shared interest, profession or background. Shared schools, universities, military units, Masonic appointments or degrees, arts, professions and hobbies have all been the qualifications for such Lodges. In some Lodges, the foundation and name may now be only of historic interest, as over time the membership evolves beyond that envisaged by its "founding brethren"; in others, the membership remains exclusive.

There are also specialist Lodges of Research, with membership drawn from Master Masons only, with interests in Masonic Research (of history, philosophy, etc.). Lodges of Research are fully warranted but, generally, do not initiate new candidates. Lodges of Instruction in UGLE may be warranted by any ordinary Lodge for the learning and rehearsal of Masonic Ritual.

Lodge Officers

Every Masonic Lodge elects certain officers to execute the necessary functions of the lodge's work. The Worshipful Master (essentially the lodge President) is always an elected officer. Most jurisdictions will also elect the Senior and Junior Wardens (Vice Presidents), the Secretary and the Treasurer. All lodges will have a Tyler, or Tiler, (who guards the door to the lodge room while the lodge is in session), sometimes elected and sometimes appointed by the Master. In addition to these elected officers, lodges will have various appointed officers—such as Deacons, Stewards, and a Chaplain (appointed to lead a non-denominational prayer at the convocation of meetings or activities—often, but not necessarily, a clergyman). The specific offices and their functions vary between jurisdictions.

Many offices are replicated at Provincial and Grand-Lodge levels, but with the addition of the word 'Grand' somewhere in the title. For example, where every lodge has a 'Junior Warden', Grand Lodges have a 'Grand Junior Warden' (or, as it is sometimes rendered, a 'Junior Grand Warden'). In addition there are a number of offices that exist only at the Grand Lodge level.[5]

Prince Hall Freemasonry

Prince Hall Freemasonry derives from historical events in the early United States that led to a tradition of separate, predominantly African-American Freemasonry in North America.

In 1775, an African-American named Prince Hall was initiated into an Irish Constitution Military Lodge then in Boston, [[Massachusetts}}, along with fourteen other African-Americans, all of whom were free-born. When the Military Lodge left North America, those fifteen men were given the authority to meet as a Lodge, form Processions on the days of the Saints John, and conduct Masonic funerals, but not to confer degrees, nor to do other Masonic work. In 1784, these individuals applied for, and obtained, a Lodge Warrant from the Premier Grand Lodge of England (GLE) and formed African Lodge, Number 459.[9]

When the UGLE was formed in 1813, all U.S.-based Lodges were stricken from their rolls–due largely to the War of 1812. Thus, separated from both UGLE and any concordantly recognized U.S. Grand Lodge, African Lodge re-titled itself as the African Lodge, Number 1 and became a de facto "Grand Lodge" (this Lodge is not to be confused with the various Grand Lodges on the Continent of Africa). As with the rest of U.S. Freemasonry, Prince Hall Freemasonry soon grew and organized on a Grand Lodge system for each state.

Widespread segregation in nineteenth- and early twentieth-century North America made it difficult for African-Americans to join Lodges outside of Prince Hall jurisdictions and impossible for inter-jurisdiction recognition between the parallel U.S. Masonic authorities.

Prince Hall Masonry has always been regular in all respects except constitutional separation, and this separation has diminished in recent years. At present, Prince Hall Grand Lodges are recognized by some UGLE Concordant Grand Lodges and not by others, but they appear to be working toward full recognition, with UGLE granting at least some degree of recognition.[10] There are a growing number of both Prince Hall Lodges and non-Prince Hall Lodges that have ethnically diverse membership.

Other degrees, orders and bodies

There is no degree in Freemasonry higher than that of Master Mason, the Third Degree.[11] There are, however, a number of organizations that require becoming a Master Mason as a prerequisite for membership.[12] These bodies have no authority over the Craft.[11] These orders or degrees may be described as additional or appendant, and often provide a further perspective on some of the allegorical, moral and philosophical content of Freemasonry.

Appendant bodies are administered separately from Craft Grand Lodges but are styled Masonic since every member must be a Mason. However, Craft Masonic jurisdictions vary in their relationships with such bodies, if a relationship exists at all. The Articles of Union of the "Modern" and "Antient" craft Grand Lodges (into UGLE in 1813) limited recognition to certain degrees, such as the Royal Arch and the "chivalric degrees," but there were and are many other degrees that have been worked since before the Union. Some bodies are not universally considered to be appendant bodies, but rather separate organizations that happen to require prior Masonic affiliation for membership. Some of these organizations have additional requirements, such as religious adherence (for example, requiring members to profess Trinitarian Christian beliefs) or membership of other bodies.

Quite apart from these, there are organizations that are often thought of as related to Freemasonry, but which are in fact not related at all and are not accorded recognition as Masonic. These include such organizations as the Orange Order, which originated in Ireland, the Knights of Pythias, or the Independent Order of Odd Fellows.

Principles and activities

While Freemasonry has often been called a "secret society," Freemasons themselves argue that it is more correct to say that it is an esoteric society, in that certain aspects are private.[11] The most common phrasing being that Freemasonry has, in the twenty-first century, become less a secret society and more of a "society with secrets." The private aspects of modern Freemasonry are the modes of recognition amongst members and particular elements within the ritual.[13] Despite the organization's great diversity, Freemasonry's central preoccupations remain charitable work within a local or wider community, moral uprightness (in most cases requiring a belief in a Supreme Being) as well as the development and maintenance of fraternal friendship—as James Anderson's Constitutions originally urged—among brethren.

Ritual, symbolism, and morality

Masons conduct their meetings using a ritualized format. There is no single Masonic ritual, and each Jurisdiction is free to set (or not set) its own ritual. However, there are similarities that exist among Jurisdictions. All Masonic ritual makes use of the architectural symbolism of the tools of the medieval operative stonemason, against the allegorical backdrop of the building of King Solomon's Temple, to convey what has been described by both Masons and critics as "a system of morality veiled in allegory and illustrated by symbols."[14] Freemasons, as speculative masons (meaning philosophical building rather than actual building), use this symbolism to teach moral and ethical lessons of the principles of "Brotherly Love, Relief, and Truth"–or as related in France: "Liberty, Equality, Fraternity."[5]

Two of the principal symbols always found in a Lodge are the square and compasses. Some Lodges and rituals explain these symbols as lessons in conduct: for example, that Masons should "square their actions by the square of virtue" and to learn to "circumscribe their desires and keep their passions within due bounds toward all mankind." However, as Freemasonry is non-dogmatic, there is no general interpretation for these symbols (or any Masonic symbol) that is used by Freemasonry as a whole.

These moral lessons are communicated in performance of allegorical ritual. A candidate progresses through degrees[11] gaining knowledge and understanding of himself, his relationship with others and his relationship with the Supreme Being (as per his own interpretation). While the philosophical aspects of Freemasonry tend to be discussed in Lodges of Instruction or Research, and sometimes informal groups, Freemasons, and others, frequently publish—to varying degrees of competence—studies that are available to the public. Any mason may speculate on the symbols and purpose of Freemasonry, and indeed all masons are required to some extent to speculate on masonic meaning as a condition of advancing through the degrees. It is well noted, however, that no one person "speaks" for the whole of Freemasonry.[15]

The Volume of the Sacred Law is always displayed in an open Lodge. In English-speaking countries, this is frequently the King James Version of the Bible or another standard translation; there is no such thing as an exclusive "Masonic Bible."[16] In many French Lodges, the Masonic Constitutions are used instead. Furthermore, a candidate is given his choice of religious text for his Obligation, according to his beliefs. UGLE alludes to similarities to legal practice in the UK, and to a common source with other oath taking processes.[17] In Lodges with a membership of mixed religions it is common to find more than one sacred text displayed.

In keeping with the geometrical and architectural theme of Freemasonry, the Supreme Being is referred to in Masonic ritual by the titles of the Great Architect of the Universe, to make clear that the reference is generic, and not tied to a particular religion's conception of God.[18]

A Tracing board is a painted or printed board that can be displayed during a ritual (Degree) of Freemasonry. Its purpose is to illustrate the symbols that the Initiate is informed about during lectures that succeed the ritual proper, and which in England are sometimes referred to as the "Tracing Board lecture." In English Freemasonry there are three Tracing boards, one for each Degree, and the Tracing boards will be changed during the ceremony according to the Degree in which the Lodge has been "opened."

Degrees

The three degrees of Craft or Blue Lodge Freemasonry are:

- Entered Apprentice—the degree of an Initiate, which makes one a Freemason;

- Fellow Craft—an intermediate degree, involved with learning;

- Master Mason—the "third degree," a necessity for participation in most aspects of Masonry.

The degrees represent stages of personal development. No Freemason is told that there is only one meaning to the allegories; as a Freemason works through the degrees and studies their lessons, he interprets them for himself, his personal interpretation bound only by the Constitution within which he works.[16] A common symbolic structure and universal archetypes provide a means for each Freemason to come to his own answers to life's important philosophical questions.

As previously stated, there is no degree of Craft Freemasonry higher than that of Master Mason.[11] Although some Masonic bodies and orders have further degrees named with higher numbers, these degrees may be considered to be supplements to the Master Mason degree rather than promotions from it.[12]

In some jurisdictions, especially those in continental Europe, Freemasons working through the degrees may be asked to prepare papers on related philosophical topics, and present these papers in open Lodge. There is an enormous bibliography of Masonic papers, magazines and publications ranging from fanciful abstractions which construct spiritual and moral lessons of varying value, through practical handbooks on organization, management and ritual performance, to serious historical and philosophical papers entitled to academic respect.

Signs, grips and words

Freemasons use signs (gestures), grips or tokens (handshakes) and words to gain admission to meetings and identify legitimate visitors.

From the early eighteenth century onwards, many exposés have been written claiming to reveal these signs, grips and passwords to the uninitiated. A classic response was deliberately to transpose certain words in the ritual, so as to catch out anyone relying on the expose. However, as Masonic scholar Christopher Hodapp states, since each Grand Lodge is free to create its own rituals, the signs, grips and passwords can and do differ from jurisdiction to jurisdiction.[5] Furthermore, historian John J. Robinson states that Grand Lodges can and do change their rituals periodically, updating the language used, adding or omitting sections.[19] Therefore, any exposé can only be valid for a particular jurisdiction at a particular time, and is always difficult for an outsider to verify. Today, an unknown visitor may be required to produce a certificate, dues card or other documentation of membership in addition to demonstrating knowledge of the signs, grips and passwords.

Obligations

Obligations are those elements of ritual in which a candidate swears to abide by the rules of the fraternity and to keep the "secrets of Freemasonry"–the various signs, tokens and words associated with recognition in each degree.[13] Obligations include the performance of certain duties while avoiding prohibited actions. In regular jurisdictions these obligations are sworn on the aforementioned Volume of the Sacred Law and in the witness of the Supreme Being and often with assurance that it is of the candidate's own free will.

Details of the obligations vary; some versions are published[13] while others are privately printed in books of coded text. Still other jurisdictions rely on oral transmission of ritual, and thus have no ritual books at all. Not all printed rituals are authentic; Leo Taxil's exposure, for example, is a proven hoax, while Duncan's Masonic Monitor (created, in part, by merging elements of several rituals then in use) was never adopted by any regular jurisdiction.

The obligations are historically known among various sources critical of Freemasonry for their so-called "bloody penalties," an allusion to the apparent physical penalties associated with each degree. This leads to some descriptions of the Obligations as "Oaths." The corresponding text, with regard to the penalties, does not appear in authoritative, endorsed sources,[13] following a decision "that all references to physical penalties be omitted from the obligations taken by Candidates in the three Degrees and by a Master Elect at his Installation but retained elsewhere in the respective ceremonies."[13] The penalties are interpreted symbolically, and are not applied in actuality by a Lodge or by any other body of Masonry. The descriptive nature of the penalties alludes to how the candidate should feel about himself should he knowingly violate his obligation. Modern penalties may include suspension, expulsion or reprimand.

While no single obligation is representative of Freemasonry as a whole, a number of common themes appear when considering a range of potential texts. Content which may appear in at least one of the three obligations includes: the candidate promises to act in a manner befitting a member of civilized society, promises to obey the law of his Supreme Being, promises to obey the law of his sovereign state, promises to attend his lodge if he is able, promises not to wrong, cheat nor defraud the Lodge or the brethren, and promises aid or charity to a member of the human family, brethren and their families in times of need if it can be done without causing financial harm to himself.[13][20]

Landmarks

The Landmarks of Masonry are defined as ancient and unchangeable precepts; standards by which the regularity of Lodges and Grand Lodges are judged. Each Grand Lodge is self-governing and no single authority exists over the whole of Freemasonry. The interpretation of these principles therefore can and does vary, leading to controversies of recognition.

The concept of Masonic Landmarks appears in Masonic regulations as early as 1723, and seem to be adopted from the regulations of operative masonic guilds. In 1858, Albert G. Mackey attempted to set down 25 Landmarks.[21] In 1863, George Oliver published a Freemason's Treasury in which he listed 40 Landmarks. A number of American Grand Lodges have attempted the task of enumerating the Landmarks; numbers differing from West Virginia (7) and New Jersey (10) to Nevada (39) and Kentucky (54).[22]

Charitable effort

The fraternity is widely involved in charity and community service activities. In contemporary times, money is collected only from the membership, and is to be devoted to charitable purposes. Freemasonry worldwide disburses substantial charitable amounts to non-Masonic charities, locally, nationally and internationally. In earlier centuries, however, charitable funds were collected more on the basis of a Provident or Friendly Society, and there were elaborate regulations to determine a petitioner's eligibility for consideration for charity, according to strictly Masonic criteria.

Some examples of Masonic charities include:

- Homes

- Education with both educational grants or schools such as the Royal Masonic School (UK) which are open to all and not limited to the families of Freemasons.

- Medical assistance.

In addition to these, there are thousands of philanthropic organizations around the world created by Freemasons. The Masonic Service Association, the Masonic Medical Research Laboratory, and the Shriners Hospitals for Children are especially notable charitable endeavors that Masons have founded and continue to support both intellectually and monetarily.

Membership requirements

A candidate for Freemasonry must petition a lodge in his community, obtaining an introduction by asking an existing member, who then becomes the candidate's proposer. In some jurisdictions, it is required that the petitioner ask three times: "Illustrious Borgnine also told of the difficulties he had in becoming a Mason. He did not know that, at the time, it was necessary to ask three times."[23] However this is becoming less prevalent.

In other jurisdictions, more open advertising is utilized to inform potential candidates where to go for more information. Regardless of how a potential candidate receives his introduction to a Lodge, he must be freely elected by secret ballot in open Lodge. Members approving his candidacy often vote with "white balls" in the voting box. A certain number of adverse votes by "black balls" will exclude a candidate. The number of adverse votes necessary to reject a candidate varies between Lodges and jurisdictions, but sometimes a single adverse vote will be enough.

General requirements

Generally, to be a regular Freemason, a candidate must:[11]

- Be a man who comes of his own free will.

- Believe in a Supreme Being. (The form of which is left to open interpretation by the candidate)

- Be at least the minimum age (from 18–25 years old depending on the jurisdiction).

- Be of good morals, and of good reputation.

- Be of sound mind and body (Lodges had in the past denied membership to a man because of a physical disability, however, now, if a potential candidate says a disability will not cause problems, it will not be held against him).

- Be free-born (or "born free," i.e. not born a slave or bondsman).[24] As with the previous, this is entirely an historical holdover, and can be interpreted in the same manner as it is in the context of being entitled to write a will. Some jurisdictions have removed this requirement.

- Have character references, as well as one or two references from current Masons, depending on jurisdiction.

Deviation from one or more of these requirements is generally the barometer of Masonic regularity or irregularity. However, an accepted deviation in some regular jurisdictions is to allow a Lewis (the son of a Mason),[25] to be initiated earlier than the normal minimum age for that jurisdiction, although no earlier than the age of 18.

Some Grand Lodges in the United States have an additional residence requirement; candidates are expected to have lived within the jurisdiction for certain period of time, typically six months.

Membership and religion

Freemasonry explicitly and openly states that it is neither a religion nor a substitute for one. "There is no separate Masonic God," nor a separate proper name for a deity in any branch of Freemasonry.[16]

Regular Freemasonry requires that its candidates believe in a Supreme Being, but the interpretation of the term is subject to the conscience of the candidate. This means that men from a wide range of faiths, including (but not limited to) Christianity, Judaism, Islam, Buddhism, Sikhism, Hinduism, etc. can and have become Masons.

Since the early nineteenth century, in the irregular Continental European tradition (meaning irregular to those Grand Lodges in amity with the United Grand Lodge of England), a very broad interpretation has been given to a (non-dogmatic) Supreme Being; in the tradition of Baruch Spinoza and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe—or views of The Ultimate Cosmic Oneness—along with Western atheistic idealism and agnosticism.

Freemasonry in Scandinavia, known as the Swedish Rite, on the other hand, accepts only Christians.[5] In addition, some appendant bodies (or portions thereof) may have religious requirements. These have no bearing, however, on what occurs at the lodge level.

Opposition to and criticism of Freemasonry

Anti-Masonry (alternatively called Anti-Freemasonry) is defined as "avowed opposition to Freemasonry."[26] There is no homogeneous anti-Masonic movement world-wide. Anti-Masonry consists of radically differing criticisms from sometimes incompatible groups who are hostile to Freemasonry in some form. They include religious groups, political groups, and conspiracy theorists.

There have been many disclosures and exposés dating as far back as the eighteenth century. These often lack context,[27] may be outdated for various reasons,[19] or could be outright hoaxes on the part of the author, as in the case of the Taxil hoax.[28]

These hoaxes and exposures have often become the basis for criticism of Masonry, usually religious (mainly Roman Catholic and evangelical Christian) or political in nature (usually Socialist or Communist dictatorial objections, but non-communists examples include the Anti-Masonic Party in the United States that led to the election of two governors). The political opposition that arose after the "Morgan Affair" in 1826 gave rise to the term "Anti-Masonry," which is still in use today, both by Masons in referring to their critics and as a self-descriptor by the critics themselves.

Religious opposition

Freemasonry has attracted criticism from theocratic states and organized religions for supposed competition with religion, or supposed heterodoxy within the Fraternity itself, and has long been the target of conspiracy theories, which see it as an occult and evil power.

Christianity and Freemasonry

Although members of various faiths cite objections, certain Christian denominations have had high profile negative attitudes to Masonry, banning or discouraging their members from becoming Freemasons.

The denomination with the longest history of objection to Freemasonry is the Catholic Church. The objections raised by the Catholic Church are based on the allegation that Masonry teaches a naturalistic deistic religion which is in conflict with Church doctrine.[29] A number of Papal pronouncements have been issued against Freemasonry. The first was Pope Clement XII's In Eminenti, April 28, 1738; the most recent was Pope Leo XIII's Ab Apostolici, October 15, 1890. The 1917 Code of Canon Law explicitly declared that joining Freemasonry entailed automatic excommunication.[30] The 1917 Code of Canon Law also forbade books friendly to Freemasonry.

In 1983, the Church issued a new Code of Canon Law. Unlike its predecessor, it did not explicitly name Masonic orders among the secret societies it condemns. It states in part: "A person who joins an association which plots against the Church is to be punished with a just penalty; one who promotes or takes office in such an association is to be punished with an interdict." This omission caused both Catholics and Freemasons to believe that the ban on Catholics becoming Freemasons may have been lifted, especially after the perceived liberalization of Vatican II. However, the matter was clarified when Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger (later Pope Benedict XVI), as the Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, issued Quaesitum est, which states: "…the Church’s negative judgment in regard to Masonic association remains unchanged since their principles have always been considered irreconcilable with the doctrine of the Church and therefore membership in them remains forbidden. The faithful who enroll in Masonic associations are in a state of grave sin and may not receive Holy Communion." Thus, from a Catholic perspective, there is still a ban on Catholics joining Masonic Lodges. For its part, Freemasonry has never objected to Catholics joining their fraternity. Those Grand Lodges in amity with UGLE deny the Church's claims and state that they explicitly adhere to the principle that "Freemasonry is not a religion, nor a substitute for religion."[16]

In contrast to Catholic allegations of rationalism and naturalism, Protestant objections are more likely to be based on allegations of mysticism, occultism, and even Satanism. Masonic scholar Albert Pike is often quoted (in some cases misquoted) by Protestant anti-Masons as an authority for the position of Masonry on these issues. However, Pike, although undoubtedly learned, was not a spokesman for Freemasonry and was controversial among Freemasons in general, representing his personal opinion only, and furthermore an opinion grounded in the attitudes and understandings of late nineteenth century Southern Freemasonry of the USA alone. Indeed his book carries in the preface a form of disclaimer from his own Grand Lodge:

In preparing this work [Pike] has been about equally Author and Compiler. (iii.) … The teachings of these Readings are not sacramental, so far as they go beyond the realm of Morality into those of other domains of Thought and Truth. The Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite uses the word "Dogma" in its true sense of doctrine, or teaching; and is not dogmatic in the odious sense of that term. Everyone is entirely free to reject and dissent from whatsoever herein may seem to him to be untrue or unsound (iv.).[31]

Since the founding of Freemasonry, many Bishops of the Church of England have been Freemasons, such as Archbishop Geoffrey Fisher. In the past, few members of the Church of England would have seen any incongruity in concurrently adhering to Anglican Christianity and practicing Freemasonry. In recent decades, however, reservations about Freemasonry have increased within Anglicanism, perhaps due to the increasing prominence of the evangelical wing of the church. The current Archbishop of Canterbury, Dr Rowan Williams, appears to harbor some reservations about Masonic ritual, while nonetheless anxious to avoid causing offense to Freemasons inside and outside the Church of England. In 2003 he felt it necessary to apologize to British Freemasons after he said that their beliefs were incompatible with Christianity and that he had barred the appointment of Freemasons to senior posts in his diocese when he was Bishop of Monmouth.

Regular Freemasonry has traditionally not responded to these claims, beyond the often repeated statement that those Grand Lodges in amity with UGLE explicitly adhere to the principle that "Freemasonry is not a religion, nor a substitute for religion. There is no separate 'Masonic deity', and there is no separate proper name for a deity in Freemasonry."[16] In recent years, however, this has begun to change. Many Masonic websites and publications now address these criticisms specifically.

Islam and Freemasonry

Many Islamic anti-Masonic arguments are closely tied with Anti-Semitism and Anti-Zionism, though other criticisms are made such as linking Freemasonry to Dajjal. Some Muslim anti-Masons argue that Freemasonry promotes the interests of the Jews around the world and that one of its aims is to rebuild the Temple of Solomon in Jerusalem after destroying the Al-Aqsa Mosque. In article 28 of its Covenant, Hamas states that Freemasonry, Rotary, and other similar groups "work in the interest of Zionism and according to its instructions…." Many countries with a significant Muslim population do not allow Masonic establishments within their jurisdictions. However, countries such as Turkey, Morocco, and Egypt have established Grand Lodges while in countries such as Malaysia and Lebanon there are District Grand Lodges operating under a warrant from an established Grand Lodge.

Political opposition

Regular Freemasonry has in its core ritual a formal obligation: to be quiet and peaceable citizens, true to the lawful government of the country in which they live, and not to countenance disloyalty or rebellion. A Freemason makes a further obligation, before being made Master of his Lodge, to pay a proper respect to the civil magistrates.[16] The words may be varied across Grand Lodges, but the sense in the obligation taken is always there. Nevertheless, much of the political opposition to Freemasonry is based upon the idea that Masonry will foment (or sometimes prevent) rebellion.

Conspiracy theorists have long associated Freemasonry with the New World Order and the Illuminati, and state that Freemasonry as an organization is either bent on world domination or already secretly in control of world politics. Historically, Freemasonry has attracted criticism—and suppression—from both the politically extreme right (e.g. Nazi Germany)[32][33] and the extreme left (e.g. the former Communist states in Eastern Europe). The Fraternity has encountered both applause for supposedly founding, and opposition for supposedly thwarting, liberal democracy (such as the United States of America).

In some countries anti-Masonry is often related to anti-Semitism and anti-Zionism. In 1980, the Iraqi legal and penal code was changed by Saddam Hussein's ruling Ba'ath Party, making it a felony to "promote or acclaim Zionist principles, including Freemasonry, or who associate [themselves] with Zionist organisations."[34] Professor Andrew Prescott of the University of Sheffield, writes: "Since at least the time of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, anti-semitism has gone hand in hand with anti-masonry, so it is not surprising that allegations that 11 September was a Zionist plot have been accompanied by suggestions that the attacks were inspired by a masonic world order."

In 1799 English Freemasonry almost came to a halt due to Parliamentary proclamation. In the wake of the French Revolution, the Unlawful Societies Act, 1799 banned any meetings of groups that required their members to take an oath or obligation. The Grand Masters of both the Moderns and the Antients Grand Lodges called on the Prime Minister William Pitt, (who was not a Freemason) and explained to him that Freemasonry was a supporter of the law and lawfully constituted authority and was much involved in charitable work. As a result Freemasonry was specifically exempted from the terms of the Act, provided that each Private Lodge's Secretary placed with the local "Clerk of the Peace" a list of the members of his Lodge once a year. This continued until 1967 when the obligation of the provision was rescinded by Parliament.

Freemasonry in the United States faced political pressure following the disappearance of William Morgan in 1826. Reports of the "Morgan Affair," together with opposition to Jacksonian democracy (Jackson was a prominent Mason) helped fuel an Anti-Masonic movement, culminating in the formation of a short lived Anti-Masonic Party which fielded candidates for the Presidential elections of 1828 and 1832.

Even in modern democracies, Freemasonry is still sometimes accused of being a network where individuals engage in cronyism, using their Masonic connections for political influence and shady business dealings. This is officially and explicitly deplored in Freemasonry. It is also charged that men become Freemasons through patronage or that they are offered incentives to join. This is not the case; no one lodge member may control membership in the lodge and in order to start the process of becoming a Freemason, an individual must ask to join the Fraternity "freely and without persuasion."[16]

In Italy, Freemasonry has become linked to a scandal concerning the Propaganda Due Lodge (aka P2). This Lodge was Chartered by the Grande Oriente d'Italia in 1877, as a Lodge for visiting Masons unable to attend their own lodges. Under Licio Gelli’s leadership, in the late 1970s, the P2 Lodge became involved in the financial scandals that nearly bankrupted the Vatican Bank. However, by this time the lodge was operating independently and irregularly; as the Grand Orient had revoked its charter in 1976.[35] By 1982 the scandal became public knowledge and Gelli was formally expelled from Freemasonry.

Holocaust

The preserved records of the Reichssicherheitshauptamt (the Reich Security Main Office) show the persecution of Freemasons. RSHA Amt VII (Written Records) was overseen by Professor Franz Six and was responsible for "ideological" tasks, by which was meant the creation of anti-Semitic and anti-Masonic propaganda. While the number is not accurately known, it is estimated that between 80,000 and 200,000 Freemasons were killed under the Nazi regime.[5] Masonic concentration camp inmates were graded as political prisoners and wore an inverted red triangle.[36]

The small blue forget-me-not flower was first used by the Grand Lodge Zur Sonne, in 1926, as a Masonic emblem at the annual convention in Bremen, Germany. In 1938 the forget-me-not badge—made by the same factory as the Masonic badge—was chosen for the annual Nazi Party Winterhilfswerk, a Nazi charitable organization which collected money so that other state funds could be freed up and used for rearmament. This coincidence enabled Freemasons to wear the forget-me-not badge as a secret sign of membership.[37][38]

After World War II, the forget-me-not flower was again used as a Masonic emblem at the first Annual Convention of the United Grand Lodges of Germany in 1948. The badge is now worn in the coat lapel by Freemasons around the world to remember all those that have suffered in the name of Freemasonry, especially those during the Nazi era.

Women and Freemasonry

Freemasonry, which is considered by many to be a fraternal organization, is sometimes criticized for not admitting women as members. Since the adoption of Anderson's constitution in 1723, it has been accepted as fact by regular Masons that only men can be made Masons. Most Grand Lodges do not admit women because they believe it would violate the ancient Landmarks. While a few women were initiated into British speculative lodges prior to 1723, officially regular Freemasonry remains exclusive to men.

While women cannot join regular lodges, there are (mainly within the borders of the United States) many female orders associated with regular Freemasonry and its appendant bodies, such as the Order of the Eastern Star, the Order of the Amaranth, the "White Shrine of Jerusalem," the "Social Order of Beauceant" and the "Daughters of the Nile." These have their own rituals and traditions founded on the Masonic model. In the French context, women in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries had been admitted into what were known as "adoption lodges" in which they could participate in ritual life. However, men clearly saw this type of adoption Freemasonry as distinct from their exclusively male variety. From the late nineteenth century onward, mixed gender lodges have met in France.

In addition, there are many non-mainstream Masonic bodies that do admit both men and women or are exclusively for women. Co-Freemasonry admits both men and women, but it is held to be irregular because it admits women. The systematic admission of women into International Co-Freemasonry began in France in 1882. In more recent times, women have created and maintained separate Lodges, working the same rituals as the all male regular lodges. These Female Masons have founded lodges around the world, and these Lodges continue to gain membership.

Notes

- ↑ David Stevenson, The Origins of Freemasonry: Scotland's Century 1590-1710 (Cambridge University Press, 1988, ISBN 978-0521353267).

- ↑ Henry Wilson Coil, Coil's Masonic Encyclopedia (Richmond, VA: Macoy Pub. & Masonic Supply Co., 1996 (original 1961), ISBN 978-0880530545).

- ↑ Frederick M. Hunter, The Regius Manuscript: A Poem On The Constitutions Of Freemasonry (Kessinger Publishing, LLC, 2010, ISBN 978-1169507203).

- ↑ Steven C. Bullock and Institute of Early American History and Culture (Williamsburg, VA), Revolutionary brotherhood: Freemasonry and the transformation of the American social order, 1730-1840 (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1996, ISBN 978-0807847503).

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 Christopher L. Hodapp, Freemasons For Dummies (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, 2005, ISBN 978-0764597961).

- ↑ GLNF: Grande Loge Nationale Francaise Grande Loge Nationale Francaise (GLNF). (in French) Retrieved February 10, 2023.

- ↑ Donald G. Campbell and Committee on Ritual, Grand Lodge F.&A.M. of California The Master Mason; Irregular and Clandestine Lodges Handbook for Candidate's Coaches. Retrieved February 10, 2023.

- ↑ Albert Gallatin Mackey, Lexicon of Freemasonry (New York, NY: Barnes & Noble, 2004, ISBN 0760760039), 445.

- ↑ Prince Hall Freemasonry: A Resource Guide Library of Congress. Retrieved February 10, 2023.

- ↑ Recognition of Prince Hall Grand Lodges in America A presentation to the Phylaxis Society March 5, 1993. Retrieved February 10, 2023.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 United Grand Lodge of England, "Aims and Relationships of the Craft," Constitutions of the Antient Fraternity of Free and Accepted Masons (Forgotten Books, 2017 (original 1815), ISBN 978-1330365311).

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Keith B. Jackson, Beyond the Craft (London: Lewis Masonic, 1980, ISBN 978-0853181187).

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 Emulation Lodge of Improvement, Emulation Ritual (Lewis Masonica, 2007, ISBN 978-0853182658).

- ↑ Hermann Gruber, Masonry (Freemasonry) The Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved February 10, 2023.

- ↑ Edward L. King, No One Person (or Organization) speaks for all of Freemasonry!. Retrieved February 10, 2023.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 16.6 The United Grand Lodge of England. Retrieved February 10, 2023.

- ↑ Margaret C. Jacob, The Origins of Freemasonry: Facts & fictions (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005, ISBN 9780812239010).

- ↑ Edward L. King, GAOTU. Retrieved February 10, 2023.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 John J. Robinson, A Pilgrim's Path (New York: M. Evans and Co., Inc., 1993, ISBN 978-0871317322).

- ↑ Charles E. Cohoughlyn-Burroughs, Bristol Masonic Ritual: The Oldest and Most Unique Craft Ritual Used in England (Kila, MT: Kessinger, 2004, ISBN 978-1417915668).

- ↑ Albert G. Mackey, "Landmarks of Freemasonry," American Quarterly Review of Freemasonry ii (October 1858): 230. Retrieved February 10, 2023.

- ↑ Michael A. Botelho, "Masonic Landmarks," The Scottish Rite Journal (February 2002).

- ↑ Ernest Borgnine, 33°, G.C., Receives 50-Year Pin, The Scottish Rite Journal (January 2001)

- ↑ John J. Robinson, Born in Blood: The Lost Secrets of Freemasonry (New York: Evans, 1989, ISBN 978-0871316028), 56.

- ↑ Dan Falconer, Freemasonry: The Lewis Pietre-Stones Review of Freemasonry. Retrieved February 10, 2023.

- ↑ "Anti-Masonry". Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. 2nd ed. 1989.

- ↑ S. Brent Morris, The Complete Idiot's Guide to Freemasonry (New York: Alpha Books, 2006, ISBN 9781592574902), 85 (also discussed in chapters 13 and 16).

- ↑ Arturo de Hoyos and S. Brent Morris, Leo Taxil Hoax - Bibliography Grand Lodge of British Columbia and Yukon. Retrieved February 10, 2023.

- ↑ Bernard Cardinal Law, Letter of April 19, 1985 to U.S. Bishops Concerning Masonry.

- ↑ Canon 2335, 1917 Code of Canon Law from Canon Law regarding Freemasonry, 1917-1983 Grand Lodge of British Columbia and Yukon. Retrieved February 10, 2023.

- ↑ Albert Pike and T. W. Hugo; Scottish Rite (Masonic order). Supreme Council of the Thirty-Third Degree for the Southern Jurisdiction. Morals and Dogma of the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite of Freemasonry. [1871] (Washington, DC: House of the Temple, 1950)

- ↑ James Wilkenson and H. Stuart Hughes, Contemporary Europe: A History (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1995, ISBN 978-0132918404), 237.

- ↑ Otto Zierer, Concise History of Great Nations: History of Germany (New York: Leon Amiel Publisher, 1976, ISBN 978-0814806739), 104.

- ↑ David R Sands, Saddam to be formally charged The Washington Times, July 1, 2004. Retrieved February 10, 2023.

- ↑ Edward L. King, P2 Lodge. Retrieved February 10, 2023.

- ↑ Israel Gutman, (ed.), Encyclopedia of the Holocaust (Macmillan Library Reference, 1990, ISBN 978-0028971667).

- ↑ Das Vergißmeinnicht-Abzeichen und die Freimaurerei, Die wahre Geschichte (in German) Internetloge.de. Retrieved February 10, 2023.

- ↑ Alain Bernheim, The Blue Forget-Me-Not": Another Side Of The Story Pietre-Stones Review of Freemasonry. Retrieved February 10, 2023.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Botelho, Michael A. "Masonic Landmarks." The Scottish Rite Journal. 2002. OCLC 21360724

- Bullock, Steven C. and Institute of Early American History and Culture (Williamsburg, Va.). Revolutionary brotherhood: Freemasonry and the transformation of the American social order, 1730-1840. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1996. ISBN 978-0807847503

- Cohoughlyn-Burroughs, Charles E. Bristol Masonic Ritual: The Oldest and Most Unique Craft Ritual Used in England. Kila, MT: Kessinger, 2004. ISBN 978-1417915668

- Coil, Henry Wilson. Coil's Masonic Encyclopedia. Richmond, VA: Macoy Pub. & Masonic Supply Co., 1996 (original 1961). ISBN 978-0880530545

- Emulation Lodge of Improvement. Emulation Ritual. Lewis Masonica, 2007. ISBN 978-0853182658

- Gutman, Israel (ed.). Encyclopedia of the Holocaust. Macmillan Library Reference, 1990. ISBN 978-0028971667

- Hodapp, Christopher L. Freemasons For Dummies. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, 2005. ISBN 978-0764597961

- Jackson, Keith B. Beyond the Craft. London: Lewis Masonic, 1980. ISBN 978-0853181187

- Jacob, Margaret C. The Origins of Freemasonry: Facts & Fictions. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005. ISBN 978-0812239010

- Katz, Israel Gutman (ed.). "Jews and Freemasons in Europe." The Encyclopedia of the Holocaust. ISBN 978-0028971667

- Mackey, Albert G. Landmarks of Freemasonry. American Quarterly Review of Freemasonry ii (1858): 230.

- Mackey, Albert Gallatin. "South," Lexicon of Freemasonry. New York, NY: Barnes & Noble, 2004. ISBN 0760760039

- McInvale, Reid. "Roman Catholic Church Law Regarding Freemasonry." Transactions of Texas Lodge of Research 27 (1991): 86–97. OCLC 47204246

- Morris, S. Brent. The Complete Idiot's Guide to Freemasonry. New York, NY: Alpha Books, 2006. ISBN 978-1592574902

- Pike, Albert and T. W. Hugo. Scottish Rite (Masonic order). Supreme Council of the Thirty-Third Degree for the Southern Jurisdiction, Morals and Dogma of the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite of Freemasonry. Washington, DC: House of the Temple, 1950.

- Robinson, John J. Born in Blood: The Lost Secrets of Freemasonry. New York: Evans, 1989. ISBN 978-0871316028

- Robinson, John J. A Pilgrim's Path. New York: M. Evans and Co., Inc., 1993. ISBN 978-0871317322

- Stevenson, David. The Origins of Freemasonry: Scotland's Century 1590-1710. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988. ISBN 978-0521353267

- United Grand Lodge of England, Constitutions of the Antient Fraternity of Free and Accepted Masons. Forgotten Books, 2017 (original 1815). ISBN 978-1330365311

- Wilkenson, James and H. Stuart Hughes. Contemporary Europe: A History. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1995. ISBN 978-0132918404

- Zierer, Otto. Concise History of Great Nations: History of Germany. New York, NY: Leon Amiel Publisher, 1976. ISBN 978-0814806739

External links

All links retrieved April 11, 2024.

- Masonic Books Online of the Pietre-Stones Review of Freemasonry

- The Constitutions of the Free-Masons (1734), James Anderson, Benjamin Franklin, Paul Royster. Hosted by the Libraries at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln

- The Mysteries of Free Masonry, by William Morgan, from Project Gutenberg

- The United Grand Lodge of England

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.