Hilary of Poitiers

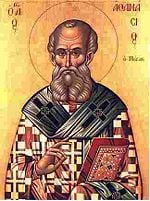

| Saint Hilarius | |

|---|---|

The Ordination of Saint Hilary. | |

| Malleus Arianorum ("hammer against Arianism") and the “Athanasius of the West” | |

| Born | ca. 300 in Poitiers |

| Died | 368 in Poitiers |

| Venerated in | Anglicanism Eastern Orthodoxy Lutheranism Oriental Orthodoxy Roman Catholicism |

| Feast | January 13 January 14 (General Roman Calendar, thirteenth century-1969) |

Saint Hilary of Poitiers (c. 300 – 368 C.E.), also known as Hilarius, was bishop of Poitiers in Gaul (today's France) and an eminent doctor of the Western Christian Church. A sometimes persecuted champion against the theological movement of Arianism, he was known as the "Athanasius of the West."

A convert from Neoplatonism, Hilary became bishop of Poitiers around 353 but was banished by Emperor Constantius II to Phrygia (in modern Turkey) in 356 for refusing to compromise in his condemnation of Arianism. While in exile he used his knowledge of Greek to create the first Latin treatises explaining the subtleties of the trinitarian controversy to his Latin brethren. From 359-360 he participated in eastern church councils, but ran afoul of imperial theology once again. After returning to Poitiers, he continued to denounce Arian bishops as heretics and wrote additional theological and polemical works.

Hilary died on January 13, which accordingly is his feast day in the Roman Catholic calendar of saints. In English educational and legal institutions, Saint Hilary's festival marks the start of the "Hilary Term." He is often associated with his disciple, Martin of Tours, in church history and tradition.

Biography

Hilary was born at Poitiers, a town in west central France about the end of the third century C.E. His parents were pagans of the nobility, and received a good education, including some knowledge of Greek, which had already become somewhat rare in the West. While he was still young, Christianity became the officially supported religion of the Roman Empire, and he later studied the Hebrew Bible and the writings of the emerging New Testament canon. Hilary, thus, abandoned his Neo-Platonism for Christianity. Together with his wife and daughter (traditionally named Saint Abra), he received the sacrament of baptism.

Bishop of Poitiers

Little is known regarding the Christian community in Poitiers at this time, but Hillary's erudition, character, and social standing were such that he won the respect the local church. Although still a married man, in his early 50s he was unanimously elected bishop, c. 353. At the time, Arianism had a strong foothold in the Western Church, especially in Gaul, where Arian Christians had often been the first missionaries to reach the formerly pagan lands. The Emperor Contantius II, meanwhile, sought to end the controversy by supporting the moderate faction later called "Semi-Arians" and denouncing the adamantly anti-Arian position represented by Patriarch Athanasius of Alexandria.

A strong proponent of the "orthodox" christology promoted by Athanasius, Hilary undertook the task of defeating the Arian view, which he considered to be a heresy that undermined the concept of Jesus' divinity and misunderstood God's plan of salvation. He refused to join in the emperor's wish that Athanasius be condemned and worked to rally the supporters of the Council of Nicaea. One of Hilary's first steps in this campaign was to organize the remaining non-Arian bishops in Gaul to excommunicate the important Semi-Arian Bishop Saturninus of Arles, together with his supporters Ursacius and Valens, on grounds of heresy.

Banishment by Constantius II

Around the same time, Hilary wrote to Emperor Constantius II in protest against actions taken against the defenders of Athanasius, some of whom had been forcibly removed from the bishoprics and sent into exile. The probable date of this letter, titled, Ad Constantium Augustum liber primus, is 355. His efforts, however, resulted in failure. Constantius summoned the synod of Biterrae (Béziers) in 356, with the professed purpose of settling the longstanding disputes once and for all. The result was that Hilary, who still refused to denounce Athanasius, was banished by imperial decree to Phrygia, where he spent nearly four years in exile.

From exile, Hilary continued to govern the non-Arian Christians in his diocese and devoted himself to writing on the theological matters which so troubled the empire and himself. During this period he prepared two of his most important contributions to dogmatic and polemical theology.

Anti-Arian writings

His De synodis (also called De fide Orientalium) was an epistle addressed in 358 to the Semi-Arian bishops in Gaul, Germany and Britain. In this work he analyzed the professions of faith uttered by the eastern bishops in the councils of Ancyra, Antioch, and Sirmium. While he criticized them as being in substance Arian, he sought to show that sometimes the difference between the doctrines of certain "heretics" and orthodox beliefs was basically a semantic one. De synodis was harshly criticized by some members of Hilary's own anti-Arian party, who thought he had shown too great a forbearance towards the Arians. He replied to their criticisms in the Apologetica ad reprehensores libri de synodis responsa.

In De trinitate libri XII, composed in 359 and 360, he attempted to express in Latin the theological subtleties elaborated in the original Greek works dealing with the Trinity—the first Latin writer to attempt this task.

More imperial troubles

In 359, Hilary attended the convocation of bishops at Seleucia Isauria, where he joined the Homoousian faction against the Semi-Arian party headed by Acacius of Caesarea. From there he went to Constantinople, and, in a petition personally presented to the emperor in 360, repudiated the accusations of his opponents and sought to vindicate the Nicene position.

Acacius, however, triumphed, as a new council of bishops held at Constantinople issued a compromise creed as a substitute for the formulas of both the Nicene and Arian parties. Although affirming the Trinity of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, the council adopted what its opponents called a firmly "Semi-Arian" position: "We affirm that the Son is like the Father." This formula was totally unacceptable to Hilary, and his repeated demands for a public debate with his opponents even after the matter had been settled to the emperor's satisfaction proved so troublesome that he was sent back to his diocese. He appears to have arrived at Poitiers about 361, within a very short time of the accession of Julian the Apostate.

Against Auxentius of Milan

After arriving back home, Hilary continued fighting both outright Arianism and the Semi-Arian formula within his diocese for two or three years. He also extended his efforts beyond Gaul. In 364, he impeached Bishop Auxentius of Milan—a man high in the imperial favor who had been the disciple of Ulfilas, the saintly Arian missionary to the Goths—as a heretic. Summoned to appear before Emperor Valentinian I at Milan to justify his charges. Hilary failed to prove his charges, and was soon expelled from Milan and sent back to Poitiers.

In 365, Hilary published the Contra Arianos vel Auxentium Mediolanensem liber, against both Auxentius and Arianism in general. Either in the same year or somewhat earlier he also wrote the highly polemical Contra Constantium Augustum liber, in which he declared that Constantius II had been the Antichrist, a rebel against God, and "a tyrant whose sole object had been to make a gift to the devil of that world for which Christ had suffered."

Final years

The later years of Hilary's life were spent in comparative quiet, devoted in part to the preparation of his expositions of the Psalms (Tractatus super Psalmos), for which he was largely indebted to Origen. He also may have written a number of hymns, and is sometimes regarded as the first Latin Christian hymnwriter, but none of the surviving compositions assigned to him is indisputable. He also composed his Commentarius in Evangelium Matthaei, an allegorical exegesis of the Gospel of Matthew and his now lost translation of Origen's commentary on the Book of Job.

Toward the end of his episcopate and with the encouragement of his disciple Martin, the future bishop of Tours, he founded a monastery at Ligugé in his diocese. He died in 368.

Legacy

In Catholic tradition, Hilary of Poitiers holds the highest rank among the Latin writers of his century prior to Ambrose of Milan. He was designated by Augustine of Hippo as "the illustrious doctor of the churches," and his works exerted an increasing influence in later centuries. Pope Pius IX formally recognized as universae ecclesiae doctor (that is, Doctor of the Church) at the synod of Bordeaux in 1851. Hilary's feast day in the Roman calendar is January 13.

The cult of Saint Hilary developed in association with that of Saint Martin of Tours as a result of Sulpicius Severus' Vita Sancti Martini and spread early to western Britain. The villages of St Hilary in Cornwall and Glamorgan and that of Llanilar in Cardiganshire bear his name. In the context of English educational and legal institutions, Saint Hilary's festival marks the start of the "Hilary Term," which begins in January.

In France the majority of shrines dedicated to Saint Hilary are to be found to the west (and north) of the Massif Central, from where the cult eventually extended to Canada. In north-west Italy the church of sant’Ilario at Casale Monferrato was dedicated to him as early as 380 C.E.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Beckwith, Carl L. Hilary of Poitiers on the Trinity: From De Fide to De Trinitate. Oxford early Christian studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008. ISBN 9780199551644.

- Hilary, and Lionel R. Wickham. Hilary of Poitiers, Conflicts of Conscience and Law in the Fourth-Century Church: "Against Valens and Ursacius," the Extant Fragments, Together with His "Letter to the Emperor Constantius." Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 1997. ISBN 9780853235729.

- Newlands, G. M. Hilary of Poitiers, A Study in Theological Method. Bern: P. Lang, 1978. ISBN 9783261031334.

- Weedman, Mark. The Trinitarian Theology of Hilary of Poitiers. Leiden: Brill, 2007. ISBN 9789004162242.

- This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

External links

All links retrieved July 17, 2024.

- Online text of Hilary's major works

- Opera Omnia Latin text of Hilary's works

- Catholic Encyclopedia: "St. Hilary of Poitiers"

- Pope Benedict XVI on Hilary of Poitiers

| This article is part of the Doctors of the Church series |

|

St. Gregory the Great | St.Ambrose | St. Augustine | St. Jerome | St. John Chrysostom | St. Basil | St. Gregory Nazianzus | St. Athanasius | St. Thomas Aquinas | St. Bonaventure | St. Anselm | St. Isidore | St. Peter Chrysologus | St. Leo the Great | St. Peter Damian | St. Bernard | St. Hilary of Poitiers | St. Alphonsus Liguori | St. Francis de Sales | St. Cyril of Alexandria | St. Cyril of Jerusalem | St. John Damascene | St. Bede the Venerable | St. Ephrem | St. Peter Canisius | St. John of the Cross | St. Robert Bellarmine | St. Albertus Magnus | St. Anthony of Padua | St. Lawrence of Brindisi | St. Teresa of Avila | St. Catherine of Siena | St. Thérèse of Lisieux |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.