| Kings of Judah |

|---|

|

Ahaz (Hebrew: אחז, an abbreviation of Jehoahaz, "God has held") was a king of Judah, the son and successor of Jotham, and father of Hezekiah. He assumed the throne at the age of 20, reigning from c. 732 until 716 B.C.E.

Ahaz faced strong military opposition from the combined forces of Syria and the northern kingdom of Israel and lost several major battles at the beginning of his reign. In this context the prophet Isaiah famously predicted the birth of the child Immanuel as a sign of Judah's deliverance from the northern threat of Assyria. Ahaz turned to the Assyrian ruler Tiglath Pileser III for aid, and succeeded in protecting Judah from destruction. However the peace resulted in the kingdom becoming the Assyria's vassal.

Ahaz adopted religious reforms that deeply offended the biblical writers. On a state visit to Damascus, he honored the Assyrian gods and added a new altar to the Temple of Jerusalem patterned after an Assyrian design. He also decreed the people of Judah freedom to worship in whatever manner they chose. Some reports indicate that Ahaz was said to have offered one of his sons as a human sacrifice.

Ahaz died at the age of 36 after a 16-year reign and was succeeded by his son Hezekiah. Hezekiah is honored in biblical tradition for restoring Judah to a strictly monotheistic religious tradition. Ahaz is one the kings mentioned in the genealogy of Jesus in the Gospel of Matthew.

Background

Ahaz was the son of Jotham and the grandson of Uzziah, who had been a highly successful king until he attempted to usurp the role of the priests by offering incense in the Temple of Jerusalem. This resulted in the alienation of the priesthood. Moreover, when Uzziah was struck with a skin disease, he was forced to live in isolation from other people and was banned from participating in the activities of the Temple. It is worth noting that the authority for determining whether a person was leprous lay with the priests.

Ahaz' father Jotham acted as co-regent during the last 15 years of Uzziah's life. As king, he seems to have have kept his place in relation to the priests, and he is also recorded as having rebuilt one of the main gates of the Temple. He warred successfully against the Amonites but faced difficulties with the Syrians, who were in league during this time with the northern kingdom of Israel. The Book of Kings says of Jotham: "He did what was right in the eyes of the Lord." As with many of the other kings of Judah, the biblical writer complains, however, that "The high places were not removed; the people continued to offer sacrifices and burn incense there."

Biography

Although the biblical writers refer to him as Ahaz, the Assyrians called Jotham's son "Yauḥazi" (Jehoahaz: "Whom Yahweh has held fast"). This name was also taken by Jehoahaz of Israel and, in a reversed form, both Ahaziah of Israel and Ahaziah of Judah—the "iah" ending being the equivalent of the "jeho" prefix, both pronounced more like yahu in Hebrew.

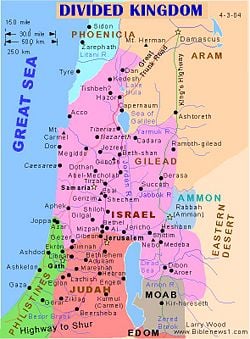

Soon after his accession as king, Ahaz faced a military coalition formed by the northern kingdom of Israel under Pekah and Damascus (Syria) under Rezin. These kings had apparently attempted to coerce Ahaz' father to join them in opposing the Assyrians, who were arming a force against Syria and Israel under the great Tiglath-Pileser III. They now intended to defeat Ahaz and replace him with a ruler who would join them in opposing the Assyrian threat. "Let us invade Judah," the prophet Isaiah characterized them as saying, "let us tear it apart and divide it among ourselves, and make the son of Tabeel king over it." (Isaiah 7:6) Who the son of Tabeel might have been is unknown, but the intention is clear that he would cooperate with the Israel-Syria coalition more closely than Ahaz would.

According to the account in the Book of Chronicles, in one phase of the ensuing war the Syrians defeated Ahaz' forces and "took many of his people as prisoners and brought them to Damascus." (2 Chron. 28:5) Pekah of Israel followed up by inflicting heavy damage to Judah's army, reportedly including 120,000 casualties in a single day.[1] Among those killed were Ahaz' sons Azrikam and Elkanah, the latter being the heir to the throne. These losses were compounded by the northerners carrying away a large number of women and children to their capital at Samaria, as well as a great deal of plunder. The prophetic party in the north, however, succeeded in influencing the northern army to return the captives. The prisoners were consequently treated kindly and sent south to Jericho together with their property.

Ahaz' worries about the threat Syria and Israel were addressed directly by Isaiah, who counseled him not to lose heart. It is in this context that Isaiah made his famous prophecy of the child Immanuel:

The Lord himself will give you a sign: The virgin (or maiden) will be with child and will give birth to a son, and will call him Immanuel... But before the boy knows enough to reject the wrong and choose the right, the land of the two kings you dread (Pekah and Rezin) will be laid waste. The Lord will bring on you and on your people and on the house of your father a time unlike any since Ephraim broke away from Judah—he will bring the king of Assyria." (Isaiah 7:14-17)

Although Isaiah had urged him not to fear Pekah and Resin, Ahaz turned to the Assyrians for protection. Externally, this strategy succeeded, for Tiglath-Pileser III invaded the kingdom of Damascus and also moved against Israel, just as Isaiah predicted, leaving Ahaz without trouble for the moment. The war lasted two years and ended in the capture and annexation of Damascus and its surrounding territory to Assyria, together with substantial territories in Israel north of Jezreel. The price Ahaz had to pay for Assyrian protection, however, was a high one, as Judah became Assyria's vassal. Ahaz also furnished help to Assyria in the form of auxiliaries for Tiglath-Pileser's army.

During the rest of his reign, Ahaz' political policy succeeded in keeping the peace in Judah, while Israel suffered as a result of its resistance to Assyrian power. It was during this time, in 722 B.C.E., that the northern capital of Samaria finally fell, and the kingdom of Israel was incorporated into the Assyrian empire.

However, what was externally a blessing for Ahaz and Judah proved to be inwardly a curse. Early in his reign, he had gone to Damascus to swear homage to the victorious Tiglath-Pileser. There, he participated in public religious ceremonies that honored the Assyrian deities. Ahaz was powerfully impressed with the glamor and prestige of the Assyrians culture, so much so that he ordered a new altar constructed in Jerusalem after the Assyrian model, making this a permanent feature of Temple worship. Changes were also made in the arrangements and furniture of the Temple.

Ahaz also carried out a decentralizing religious reform, allowing people to worship wherever they wished, rather than only in Jerusalem's temple. These reforms earned him the absolute condemnation of the biblical writers, who recorded not only that he worshiped at the high places, but even that he offered his son as a human sacrifice by fire. (Chronicles says "sons" rather than the singular "son" given by Kings.) No information is known about the ages of these son(s) or their place in the royal succession.

Ahaz died after a 16-year reign at the age of 36. Despite his external success of keeping Judah alive while Israel fell to the Assyrians, his biblical epitaph reads: "He walked in the ways of the kings of Israel… following the detestable ways of the nations the Lord had driven out before the Israelites." (2 Kings 16:3)

Legacy

Despite enabling Judah to avoid the tragic fate of Israel and Syria, Ahaz is viewed by history as an evil king whose government, on the whole, was harmful to his country. Critical scholarship casts doubt on the characterization of Ahaz. In this view, Ahaz deserves credit for preventing his country from falling to the Assyrians. Moreover, the prophet Isaiah did not actually denounce him and seems to have encouraged him in the belief that Assyria would come to his aid against Israel and Syria. Moreover, Ahaz' policy of religious reform, although hateful to the biblical writers, encouraged religious pluralism. While no one defends human sacrifice, some suggest that his causing his son to "pass through the fire" may have constituted something other than an ordeal unto death, or even that such an offering was made to Yahweh rather than a heathen deity. (A precedent exists in the case of the judge Jephthah, who sacrificed his daughter as a burnt offering to Yahweh after a military victory). In any case, his changing the design of the altar in the Temple of Jerusalem had the support of the priesthood and may have been seen at the time as an improvement.

Ahaz' son Hezekiah eventually returned the nation to the strict monotheistic form of worship. Hezekiah also attempted to revolt against Assyria's suzerainty, resulting in the loss of every city except Jerusalem to the forces of Sennacherib. He eventually had to settle, as Ahaz did, on remaining as Assyria's vassal. Hezekiah's reign is nonetheless seen as a golden era in which Judah finally returned, albeit briefly, to the true worship of God.

According to the rabbinical tradition, Ahaz was a king who persisted in his wickedness and would not repent (Sanh. 103a, Meg. 11a). Worse than this, he threatened Israel's religion to its very foundation in an attempt to destroy all hope of regeneration. He closed the schools so that no instruction should be possible. During his reign, Isaiah had to teach in secret (Yer. Sanh. x. 28b; Gen. R. xlii). His one redeeming feature was that he always humbly submitted to the prophet's rebukes (Sanh. 104a).

Whatever the case may be concerning his record as a king, both Jewish and Christian tradition agree that Ahaz is one of the ancestors of the Messiah.

| House of David | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by: Jotham |

King of Judah Coregency: 736 – 732 B.C.E. Sole reign: 732 – 716 B.C.E. |

Succeeded by: Hezekiah |

Notes

- ↑ As with many battle statistics in the Bible, this figure is thought by modern scholars to be exaggerated.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Albright. William F. The Archaeology of Palestine, 2nd ed. Peter Smith Pub., Inc. 1985. ISBN 0844600032.

- Bright, John. A History of Israel, 4th ed. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2000. ISBN 0664220681.

- Galil, Gershon. The Chronology of the Kings of Israel and Judah. Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers, 1996. ISBN 9004106111.

- Grant, Michael. The History of Ancient Israel. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1984. ISBN 0684180812.

- Grena, G. M. 2004. LMLK—A Mystery Belonging to the King vol. 1. 4000 Years of Writing History. 2004. ISBN 097487860X.

- Miller, J. Maxwell. A History of Ancient Israel and Judah. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 1986. ISBN 066421262X.

- Silberman, Neil Asher, and Israel Finkelstein. The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts. New York: Free Press, 2002. ISBN 0684869136.

This article incorporates text from the Jewish Encyclopedia, a publication now in the public domain.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.