| Category |

| Jews · Judaism · Denominations |

|---|

| Orthodox · Conservative · Reform |

| Haredi · Hasidic · Modern Orthodox |

| Reconstructionist · Renewal · Rabbinic · Karaite |

| Jewish philosophy |

| Principles of faith · Minyan · Kabbalah |

| Noahide laws · God · Eschatology · Messiah |

| Chosenness · Holocaust · Halakha · Kashrut |

| Modesty · Tzedakah · Ethics · Mussar |

| Religious texts |

| Torah · Tanakh · Talmud · Midrash · Tosefta |

| Rabbinic works · Kuzari · Mishneh Torah |

| Tur · Shulchan Aruch · Mishnah Berurah |

| Ḥumash · Siddur · Piyutim · Zohar · Tanya |

| Holy cities |

| Jerusalem · Safed · Hebron · Tiberias |

| Important figures |

| Abraham · Isaac · Jacob/Israel |

| Sarah · Rebecca · Rachel · Leah |

| Moses · Deborah · Ruth · David · Solomon |

| Elijah · Hillel · Shammai · Judah the Prince |

| Saadia Gaon · Rashi · Rif · Ibn Ezra · Tosafists |

| Rambam · Ramban · Gersonides |

| Yosef Albo · Yosef Karo · Rabbeinu Asher |

| Baal Shem Tov · Alter Rebbe · Vilna Gaon |

| Ovadia Yosef · Moshe Feinstein · Elazar Shach |

| Lubavitcher Rebbe |

| Jewish life cycle |

| Brit · B'nai mitzvah · Shidduch · Marriage |

| Niddah · Naming · Pidyon HaBen · Bereavement |

| Religious roles |

| Rabbi · Rebbe · Hazzan |

| Kohen/Priest · Mashgiach · Gabbai · Maggid |

| Mohel · Beth din · Rosh yeshiva |

| Religious buildings |

| Synagogue · Mikvah · Holy Temple / Tabernacle |

| Religious articles |

| Tallit · Tefillin · Kipa · Sefer Torah |

| Tzitzit · Mezuzah · Menorah · Shofar |

| 4 Species · Kittel · Gartel · Yad |

| Jewish prayers |

| Jewish services · Shema · Amidah · Aleinu |

| Kol Nidre · Kaddish · Hallel · Ma Tovu · Havdalah |

| Judaism & other religions |

| Christianity · Islam · Catholicism · Christian-Jewish reconciliation |

| Abrahamic religions · Judeo-Paganism · Pluralism |

| Mormonism · "Judeo-Christian" · Alternative Judaism |

| Related topics |

| Criticism of Judaism · Anti-Judaism |

| Antisemitism · Philo-Semitism · Yeshiva |

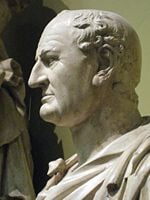

Yochanan ben Zakai (Hebrew: יוחנן בן זכאי, died 80-90 C.E.), also spelled Johanan b. Zakki, was an important rabbinical sage in the final days of the Second Temple era of Judaism and a key figure in the transition from Temple-centered to Rabbinical Judaism.

Already a well known teacher in Jerusalem before the Jewish Revolt of 66-70 C.E., Yochanan was smuggled out of the city during the rebellion and convinced the future emperor Vespasian to allow him to reestablish his academy at Jamnia. This institution became the leading center of Judaism after the Temple was destroyed. Under Yochanan's influence, animal sacrifices were abandoned in favor of prayer as the primary means of atonement between man and God. The active Jewish priesthood thus came to an end and was replaced by the rabbinical tradition. Yochanan also facilitated the ascendancy of the relatively liberal teachings of Hillel over the stricter attitude of Shammai in the Council of Jamnia (70-90 C.E.) and subsequent Jewish tradition.

One of the first generation of the sages known as the tannaim, he and his students became primary contributors to the core Jewish texts, namely the Mishnah and the Talmud, which relate many teachings and legends associated with him.

Life

Little is know about Yochanan's early life and family, but the Mishnah portrays him as a merchant in the first third of his life, as a student in the the second third, and a teacher for the final third. However, it also speaks of his life, like that of Moses, as lasting 120 years (Rosh haShanah 30b).

In a less legendary sense, Yochanan is considered an important link in the chain of Pharisaic teaching, passing on the wisdom of both Hillel and Shammai to subsequent generations (Pirkei Abot 2:8). Generally, however, he is associated more with Hillel's views than those of Shammai (Sukkot 28a), and is said to have been Hillel's youngest pupil.

The Talmud reports that, in the mid first century, he was particularly active in refuting the Sadducees' interpretations of Jewish law (Menahot 65a, Bava Batra 115b), as opposed to those of his own party, the Pharisees. He even prevented the Jewish high priest, who was a Sadducee, from following the Sadducean interpretation of the Red Heifer purification ritual (Tosef., Parah 3:8 ).

His school in Jerusalem was called the "great house" and was the scene of many incidents preserved in later history and legend (Lam. R. i. 12; Gen. R. iv). An old tradition (Pes. 26a) relates that Yochanan sat in the shadow of the Temple and lectured the whole day. Like the prophet Jeremiah before him, and like the Christian Messiah Jesus of Nazareth, he prophesied against the Temple of Jerusalem, saying: "O Temple, Temple, why dost thou frighten thyself? I know of thee that thou shalt be destroyed" (Yoma 39b).

Although he taught in Jerusalem, he also maintained a home in a town called Arab in the Galilee. There, he found the indifference of the Galileans on matters of Sabbath observance to be disturbing, reportedly exclaiming: "O Galilee, Galilee, thou hatest the Torah; hence wilt thou fall into the hands of robbers" (Shab. xvi. 7, xxii. 3).

During the Jewish Revolt of 66-70 C.E., Yochanan argued in favor of peace. When internal strife between the Jewish factions in the city became intolerable to him, he arranged through his disciples Eliezer ben Hyrcanus and Joshua ben Hananiah to be smuggled out of the city in a coffin, so that he could negotiate with Vespasian. This military commander, who would later became emperor, granted Johanan permission to resettle in Jamnia and reestablish his academy there, an event which would come to have major importance in the survival and later history of the Jewish religion.

After the destruction of Jerusalem and its sacred temple, Yochanan converted his school into the Jewish religious center, successfully insisting that privileges given by Jewish law to Jerusalem should be transferred to Jamnia (Rosh haShanah 4:1-3). His academy also came to act as a place of Jerusalem's Jewish legislative council, the Sanhedrin. He soon convened the lengthy Council of Jamnia, traditionally dated as lasting from 70 to 90 C.E., to decide how to deal with the loss of the crucial sacrificial altars of the Temple of Jerusalem, and other pressing questions.

This discussion resulted in the replacement of the Jewish priesthood by the rabbinate as the primary Jewish religious authority. Referring to a famous passage in the Book of Hosea, I desire mercy, and not sacrifice (Hosea 6:6), Yochanan helped persuade the council to replace animal sacrifice with prayer (Rabbi Nathan, Abot 4), a practice that continues until today. The council also resulted in the ascendancy of the House of Hillel over that of Shammai, whose strict anti-Gentile policy had led to the disaster of the Jewish Revolt against Rome.

In his last years, Yochanan taught at Berur Hayil (Sanhedrin 32b), a location near Jamnia. His students were present at his deathbed. The Talmud records his last words, which seem to relate to the advent of the Jewish Messiah: "Prepare a throne for Hezekiah, the King of Judah, who is coming" (Berakot 28b).

Some scholars place his death as 80 C.E., with the Council of Jamnia continuing after his demise. In any case, his disciples returned to Jamnia upon his death, and he was buried in the city of Tiberias. In his role as leader of the Jewish Council, he was succeeded by Gamaliel II.

Teachings and character

Despite being the most influential rabbi of his time, Yochanan ben Zakai is not associated with any major Jewish legal rulings of his own beyond the matter of the Red Heifer ceremony mentioned above. On the other hand, numerous important homiletic and exegetical sayings are attributed to him. In addition, many of the rulings attributed to the House of Hillel may have passed into tradition through his teaching.

Jewish tradition records Yochanan as being extremely dedicated to religious study, claiming that he was always the last to leave the academy and that "no one ever found him engaged in anything but study" (Sukkot 28a). His motto was: "If thou hast learned much of the Torah, do not take credit for it; for this was the purpose of thy creation" (Ab. 2:8). On the other hand, he warned against an obsessive devotion to study, emphasizing that piety was just as important as scholarship: "Whoever possesses both these characteristics at the same time is like an artist who has his tools in his hands" (Ab. R. N. 22). He also argued that Job's piety was not based on the love of God, but on the fear of Him (Soṭah 5:5).

"Benevolence on the part of a nation," said Rabbi Yochanan, "has the atoning power of a sin-offering" (B. B. l.c.). Regarding the coming of the Messiah, he seems to have adopted a somewhat skeptical view, possibly considering the numerous messianic pretenders of his day, saying: "If you are holding a sapling in your hand and someone tells you, 'Come quickly, the Messiah is here!,' first finish planting the tree and then go to greet the Messiah" (Rabbi Nathan, Abot, 31b).

Yochanan's pupil, Rabbi Joshua ben Hananiah, reportedly occupied himself with esoteric doctrines under the watchful eye of his master, and Rabbi Akiva in turn inherited these mystical truths from Rabbi Joshua (Ḥag. 14b). A remarkable saying of Yochanan's has been preserved (Ḥag. 13a; comp. Pes. 94b), in which man is advised to bring the infinity of God nearer to his own conception by imagining the space of the cosmos extended to unthinkable distances.

One day, probably not long after the destruction of Jerusalem, Yochanan saw a starving young Jewess picking out grains of barley from the dung of an Arab's horse. Yochanan interpreted the sad scene as a fulfillment of the prophecy of Deut. 18:47-48: "Because thou servedst not the Lord thy God with joyfulness… therefore shalt thou serve thine enemies, which the Lord shall send against thee, in hunger and in thirst, and in nakedness, and in want of all things" (Yitro, Baḥodesh, 1).

Legacy

Tradition holds that Yochanan ben Zakai felt the fall of his people more deeply than anyone else, but he did more than anyone to prepare the way for Judaism and Israel to rise again. Certainly it is a historical fact that he was a key figure in the establishment of post-Second Temple Judaism and that he bridged the first rabbinical sages and their successors in the second century C.E., who laid the foundations of the Mishnah and the Talmud. Like Jeremiah and Ezekiel before him, he became the spiritual leader of his people in the early days of their new exile from Jerusalem after yet another destruction of the Temple. Through him, a long line of Judaism's key tannaim was spiritually descended, from Joshua ben Hananiah to Akiva and finally Judah haNasi, the compiler of the Mishnah.

A synagogue in modern Israel, named the Rabban Yochanan ben Zakai Synagogue, is held by Jewish legend to be sited at the place of Johanan's final prayers, prior to his escape from Jerusalem. A religious moshav (similar to a kibbutz) in central Israel, Ben Zakai, is also named after him.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Duker, Jonathan. The Spirits Behind the Law: The Talmudic Scholars. Jerusalem: Urim, 2007. ISBN 9789657108970.

- Green, William Scott. Persons and Institutions in Early Rabbinic Judaism. Brown Judaic studies, no. 3. Missoula, MT: Published by Scholars Press for Brown University, 1977. ISBN 9780891301318.

- Kalmin, Richard Lee. The Sage in Jewish Society of Late Antiquity. New York: Routledge, 1999. ISBN 9780415196956.

- Neusner, Jacob. First-Century Judaism in Crisis: Yohanan Ben Zakkai and the Renaissance of Torah. New York: Ktav Pub. House, 1982. ISBN 9780870687280.

External links

All links retrieved May 24, 2023.

- JOHANAN B. ZAKKAI JewishEncyclopedia.com

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.