| Western Philosophers Nineteenth-century philosophy | |

|---|---|

| |

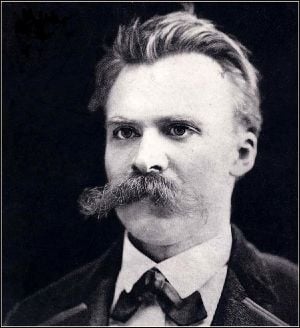

| Name: Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche | |

| Birth: October 15, 1844 (Röcken bei LĂŒtzen, Saxony, Prussia) | |

| Death: August 25, 1900 (Weimar, Germany) | |

| School/tradition: Precursor to Existentialism | |

| Main interests | |

| Ethics, Metaphysics, Epistemology, Aesthetics, Language | |

| Notable ideas | |

| Eternal Recurrence, Will to Power, Nihilism, Herd Instinct, Overman, Attack on Christianity | |

| Influences | Influenced |

| Burckhardt, Emerson, Goethe, Heraclitus, Montaigne, Schopenhauer, Wagner | Foucault, Heidegger, Iqbal, Jaspers, Sartre, Deleuze, Freud, Camus, Rilke, Bataille |

The German philosopher Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (October 15, 1844 â August 25, 1900) is known as one of the main representatives of atheistic philosophy. He is famous for the phrase, âGod is dead.â However, he is often characterized as the most religious atheist. In this contradictory tension, lies the enigmatic thinker, Nietzsche, who raised a number of fundamental questions that challenge the root of the philosophical tradition of the West. Among the most poignant are his criticisms of Christianity and the Western trust in rationality. Nietzscheâs sincere and uncompromising quest for truth and his tragic life have touched the hearts of a wide range of people. Critics hold that Nietzsche's atheistic and critical thought confused and misguided subsequent thinkers and led to arbitrary moral behavior.

Radical Questioning

If a philosopher is to be a pioneer of thought, trying to open up a new path to truth, he or she inevitably has to challenge existing thoughts, traditions, authorities, accepted beliefs, and presuppositions other people take for granted. The advancement of thought is often only possible once the unrealized presuppositions of predecessors are identified, brought to the foreground, and examined. Using Thomas Kuhnâs terminology, one could say that existing paradigms of thought have to be questioned. A philosophy is said to be radical (âradixâ in Latin, means ârootâ) when it reveals and questions the deepest root of thought. In this sense, Nietzsche is a foremost radical thinker and a pioneer of thought for all ages. Nietzsche questioned the two roots of Western thought, i.e., Christianity and the trust in the power of reason. That trust in reason stems from Greek philosophy and has descended all the way to modern philosophy.

Jesus vs. Christianity

As for Christianity, Nietzsche first questions the justification of the crucifixion of Jesus. Nietzsche asks: Was Jesus supposed to die on the cross? Was not the crucifixion of Jesus a mistake due to the disbelief of his disciples? Was the doctrine of faith in the cross and the idea of redemption not an invention by Paul? Did Paul not invent this new doctrine and a new religion called Christianity in order to justify his disbelief and mistake that led Jesus to the cross? Was Christianity not far from Jesusâ own teaching? Did the crucifixion of Jesus not terminate the possibility of âreal happiness on the earth?â Nietzsche wrote:

One now begins to see just what it was that came to an end with the death on the cross: a new and thoroughly original effort to found a Buddhistic peace movement, and so establish happiness on earthâreal, not merely promised (Antichrist 42).

For Nietzsche, happiness on earth was the issue, regardless of what Buddhism really was. âBuddhism promises nothing, but actually fulfills; Christianity promises everything, but fulfills nothing.â Nietzsche accused Paul of being the inventor of a new religion called Christianity and a person who distorted the âhistorical truth.â

Above all, the Savior: he (Paul) nailed him to his own cross. The life, the example, the teaching, the death of Christ, the meaning and the law of the whole gospelsânothing was left of all this after that counterfeiter in hatred had reduced it to his uses. Surely not reality; surely not historical truth! (Antichrist 42)

Nietzsche made a sharp distinction between Jesus and Christianity. While he severely criticized Christianity, he had a high esteem for Jesus: ââI shall go back a bit, and tell you the authentic history of Christianity.âThe very word âChristianityâ is a misunderstandingâat bottom there was only one Christian, and he died on the cross. The âGospelsâ died on the crossâ (Antichrist 39). For Nietzsche, Jesus is the only âauthentic Christianâ who lived according to what he taught.

Questioning Rationality

Nietzsche also questioned the entire philosophical tradition of the West, which developed based on trust in the power of reason. He asked: Isnât there a deeper unconscious motive underneath the exercise of reason? Is a theory not a matter of justification, an invention in order to conceal that motive? Is a human being not far more complex than a mere rational being? Can rationality be the root of philosophical discourse? Is thinking not dominated by other forces in consciousness, forces one is not aware of? Did Western philosophy not take the wrong path? Thus, Nietzsche questions the way Western philosophy has developed and its trust in rationality that can be traced back to Greek philosophy.

Nietzsche was prophetic in the sense that he raised fundamental questions about the two key traditions of the WestâChristianity and philosophy. His life was tragic, because not only could no one answer him, but also no one understood the authenticity of his questions. Even his well-known phrase, âGod is dead,â has a tragic tone.

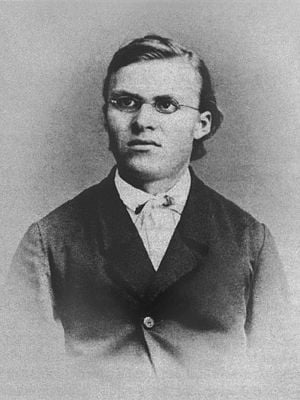

Nietzsche grew up as an innocent and faithful child nicknamed the âsmall priest,â singing hymns and citing biblical verses in front of others. When he was ten or twelve, he expressed his question about God in an essay entitled âDestiny and History.â In Daybreak (Book I), which Nietzsche wrote right after his resignation from professorship, he asks, âWould he not be a cruel god if he possessed the truth and could behold mankind miserably tormenting itself over the truth?â (Clark 92). The question, if God is almighty, why did he not simply tell us the truth and save us, who were terribly suffering and seeking for truth, is a question we all may have had in our mind. In the phrase, âGod is dead,â donât we hear Nietzscheâs tormented heart asking God to answer the question?

Nietzsche is among the most readable of philosophers and penned a large number of aphorisms and varied experimental forms of composition. Although his work was distorted and thus identified with Philosophical Romanticism, Nihilism, Anti-Semitism, and even Nazism, he himself vociferously denied such tendencies in his work, even to the point of directly opposing them. In philosophy and literature, he is often identified as an inspiration for existentialism and postmodernism. His thought is, by many accounts, most difficult to comprehend in any systematized form and remains a vivacious topic of debate.

Biography

Friedrich Nietzsche was born on October 15, 1844, in the small town of Röcken, which is not far from LĂŒtzen and Leipzig, within what was then the Prussian province of Saxony. He was born on the 49th birthday of King Friedrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia and was thus named after him. His father was a Lutheran pastor, who died of encephalomalacia/ in 1849, when Nietzsche was four years old. In 1850, Nietzsche's mother moved the family to Naumburg, where he lived for the next eight years before heading off to boarding school at the famous and demanding Schulpforta. Nietzsche was now the only male in the house, living with his mother, his grandmother, two paternal aunts, and his sister Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche. As a young man, he was particularly vigorous and energetic. In addition, his early piety for Christianity is born out by the choir Miserere, which was dedicated to Schulpforta while he attended.

After graduation, in 1864, he commenced his studies in classical philology and theology at the University of Bonn. He met the composer Richard Wagner, of whom he was a great admirer, in November 1868 and their friendship developed for a time. A brilliant scholar, he became special professor of classical philology at the University of Basel in 1869, at the uncommon age of 24. Professor Friedrich Ritschl at the University of Leipzig became aware of Nietzsche's capabilities from some exceptional philological articles he had published, and recommended to the faculty board that Nietzsche be given his doctorate without the typically required dissertation.

At Basel, Nietzsche found little satisfaction in life among his philology colleagues. He established closer intellectual ties with the historian Jakob Burckhardt, whose lectures he attended, and the atheist theologian Franz Overbeck, both of whom remained his friends throughout his life. His inaugural lecture at Basel was Ăber die Persönlichkeit Homers (On Homer's Personality). He also made frequent visits to the Wagners at Tribschen.

When the Franco-Prussian War erupted in 1870, Nietzsche left Basel and, being disqualified for other services due to his citizenship status, volunteered as a medical orderly on active duty. His time in the military was short, but he experienced much, witnessing the traumatic effects of battle and taking close care of wounded soldiers. He soon contracted diphtheria and dysentery and subsequently experienced a painful variety of health difficulties for the remainder of his life.

Upon returning to Basel, instead of waiting to heal, he pushed headlong into a more fervent schedule of study than ever before. In 1870, he gave Cosima Wagner the manuscript of The Genesis of the Tragic Idea as a birthday gift. In 1872, he published his first book, The Birth of Tragedy in which he denied Schopenhauer's influence upon his thought and sought a "philology of the future" (Zukunftsphilologie). A biting critical reaction by the young and promising philologist, Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff, as well as its innovative views of the ancient Greeks, dampened the book's reception and increased its notoriety, initially. After it settled into the philological community, it found many rings of approval and exultation of Nietzsche's perspicacity. To this day, it is widely regarded as a classic piece.

In April 1873, Wagner incited Nietzsche to take on David Friedrich Strauss. Wagner had found his book, Der alte und der neue Glaube, to be shallow. Strauss had also offended him by siding with the composer and conductor Franz Lachner, who had been dismissed on account of Wagner. In 1879, Nietzsche retired from his position at Basel. This was due either to his declining health or in order to devote himself fully toward the ramification of his philosophy which found further expression in Human, All-Too-Human. This book revealed the philosophic distance between Nietzsche and Wagner; this, together with the latter's virulent Anti-Semitism, spelled the end of their friendship.

From 1880 until his collapse in January 1889, Nietzsche led a wandering existence as a stateless person, writing most of his major works in Turin. After his mental breakdown, both his sister Elisabeth and mother Franziska Nietzsche cared for him. His fame and influence came later, despite (or due to) the interference of Elisabeth, who published selections from his notebooks with the title The Will to Power, in 1901, and maintained her authority over Nietzsche's literary estate after Franziska's death in 1897.

His mental breakdown

Nietzsche endured periods of illness during much of his adult life. In 1889, after the completion of Ecce Homo, an autobiography, his health rapidly declined until he collapsed in Turin. Shortly before his collapse, according to one account, he embraced a horse in the streets of Turin because its owner had flogged it. Thereafter, he was brought to his room and spent several days in a state of ecstasy writing letters to various friends, signing them "Dionysus" and "The Crucified." He gradually became less and less coherent and almost entirely uncommunicative. His close friend Peter Gast, who was also an apt composer, observed that he retained the ability to improvise beautifully on the piano for some months after his breakdown, but this too eventually left him.

The initial emotional symptoms of Nietzsche's breakdown, as evidenced in the letters he sent to his friends in the few days of lucidity remaining to him, bear many similarities to the ecstatic writings of religious mystics insofar as they proclaim his identification with the godhead. These letters remain the best evidence available for Nietzsche's own opinion on the nature of his breakdown. Nietzsche's letters describe his experience as a radical breakthrough in which he rejoices, rather than laments. Most Nietzsche commentators find the issue of Nietzsche's breakdown and "insanity" irrelevant to his work as a philosopher, for the tenability of arguments and ideas are more important than the author. There are some, however, including Georges Bataille, who insist that Nietzsche's mental breakdown be considered.

Nietzsche spent the last ten years of his life insane and in the care of his sister Elisabeth. He was completely unaware of the growing success of his works. The cause of Nietzsche's condition has to be regarded as undetermined. Doctors later in his life said they were not so sure about the initial diagnosis of syphilis because he lacked the typical symptoms. While the story of syphilis indeed became generally accepted in the twentieth century, recent research in the Journal of Medical Biography shows that syphilis is not consistent with Nietzsche's symptoms and that the contention that he had the disease originated in anti-Nietzschean tracts. Brain cancer was the likely culprit, according to Dr. Leonard Sax, director of the Montgomery Centre for Research in Child Development. Another strong argument against the syphilis theory is summarized by Claudia Crawford in the book To Nietzsche: Dionysus, I Love You! Ariadne. The diagnosis of syphilis is supported, however, in Deborah Hayden's Pox: Genius, Madness, and the Mysteries of Syphilis. His handwriting in all the letters that he had written around the period of the final breakdown showed no sign of deterioration.

His Works and Ideas

Style of Thought

Nietzsche was probably the philosopher who best understood the complexity of human being and his discourse. Thinking is not simply a logical and intellectual process, but it involves beliefs, imagination, commitment, emotional feelings, desires, and other elements. Nietzsche presents or rather describes his thoughts in images, poetic prose, stories, and symbols. Conceptualization of his thought is therefore a complex interpretive process. For this reason, it is said, âeveryone has his or her own interpretive reading of Nietzsche.â

Nietzsche is unique among philosophers in his prose style, particularly in the Zarathustra. His work has been referred to as half philosophic, half poetic. Equally important are punning and paradox in his rhetoric, but some of the nuances and shades of meaning are lost in translation into English. A case in point is the thorny issue of the translation of Ăbermensch and its unfounded association with both the heroic character Superman and the Nazi party and philosophy.

God is dead

Nietzsche is well-known for the statement "God is dead." While in popular belief it is Nietzsche himself who blatantly made this declaration, it was actually placed into the mouth of a character, a "madman," in The Gay Science. It was also later proclaimed by Nietzsche's Zarathustra. This largely misunderstood statement does not proclaim a physical death, but a natural end to the belief in God being the foundation of the Western mind. It is also widely misunderstood as a kind of gloating declaration, when it is actually described as a tragic lament by the character Zarathustra.

"God is Dead" is more of an observation than a declaration, and it is noteworthy that Nietzsche never felt the need to advance any arguments for atheism, but merely observed that, for all practical purposes, his contemporaries lived "as if" God were dead. Nietzsche believed this "death" would eventually undermine the foundations of morality and lead to moral relativism and moral nihilism. To avoid this, he believed in re-evaluating the foundations of morality and placing them not on a pre-determined, but a natural foundation through comparative analysis.

Nietzsche did not take Godâs death lightly. He saw its tremendous magnitude and consequences. In âGay Scienceâ 125, Nietzsche describes the magnitude of Godâs death:

God is dead! God remains dead! And we have killed him! How shall we console ourselves, the most murderous of all murderers? The holiest and the mightiest that the world has hitherto possessed, has bled to death under our knife - who will wipe the blood from us? With what water could we cleanse ourselves? What lustrums, what sacred games shall we have to devise? Is not the magnitude of this deed too great for us?

In Nietzscheâs mind, there might be an overlap here between the tragic crucifixion of Jesus and the âmurdering of God.â Since Nietzsche was a genius at expressing multiple meanings in a single phrase, this is a very real possibility.

Jesus and Christianity

In The Antichrist, Nietzsche attacked Christian pedagogy for what he called its "transvaluation" of healthy instinctive values. He went beyond agnostic and atheistic thinkers of the Enlightenment, who felt that Christianity was simply untrue. He claimed that it may have been deliberately propagated as a subversive religion (a "psychological warfare weapon" or what some would call a "mimetic virus") within the Roman Empire by the Apostle Paul as a form of covert revenge for the Roman destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple during the Jewish War. However, in The Antichrist, Nietzsche has a remarkably high view of Jesus, claiming that the scholars of the day fail to pay any attention to the man, Jesus, and only look to their construction, Christ.

Overman (Ăbermensch)

After the death of God, the world became meaningless and devoid of value. Nietzsche called it a world of nihilism. There is no value, meaning, and purpose in such a life, since God is the source and foundation of all values. In that godless world, who or what should we look for? Nietzsche presents the âovermanâ or âsupermanâ (Ăbermensch) as the image of a human being who can overcome the Godless world of nihilism. In a short passage of âZarathustraâs Prologueâ in Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Nietzsche writes:

I TEACH YOU THE SUPERMAN. Man is something that is to be surpassed. What have ye done to surpass man? All beings hitherto have created something beyond themselves: and ye want to be the ebb of that great tide, and would rather go back to the beast than surpass man?

In the same Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Nietzsche portrays the overman as the image of life that can tolerate the thought of the eternal recurrence of the same, the ultimate form of nihilism.

For Nietzsche, life on earth was always the issue. His lament over the crucifixion of Jesus and his accusations against Paul arose from his concern for happiness on earth. Nietzsche introduced the overman as the hope human beings can look for. He is more like an ideal man who can become the lord of the earth. The existing human being is a ârope between overman and beast.â Human beings are yet âtoo human to become an overman.â Nietzsche characterizes the overman as the âmeaning of the earth" in contrast to otherworldly hopes.

The Superman is the meaning of the earth. Let your will say: The Superman SHALL BE the meaning of the earth!

I conjure you, my brethren, REMAIN TRUE TO THE EARTH, and believe not those who speak unto you of superearthly hopes! Poisoners are they, whether they know it or not. (Thus Spoke Zarathustra âZarathustraâs Prologueâ)

Interpreting the overman as a superhero or a superhuman being would be wrong. This misinterpretation was developed by those who have linked Nietzscheâs thought to Nazi propaganda. Their misrepresentation was caused partly by the ambiguity of this concept.

Child, Play and Joy

In âZarathustraâ, Nietzsche explains the threefold metamorphoses of the human spirit: from a camel to a lion, and from a lion to a child. A camel is obedient; it has an attitude to carry burdens, symbolizing the spirit of medieval Christianity. A lion is a free spirit, representing the free Enlightenment individual of modernity. What, then, does the child represent for Nietzsche, who placed him at the last stage?

Innocence is the child, and forgetfulness, a new beginning, a game, a self-rolling wheel, a first movement, a holy Yea. (âZarathustraâ The Three Metamorphoses)

The ego-centered or self-conscious adult is more like a lion. An individual according to the ideal of the Enlightenment is a free spirit who is free from all bondage to the past, tradition, and authority. He or she is free to think and act. However, Nietzsche points out the deficiency of a free spirit. The modern individual does not realize that oneâs life is given as a kind of fate. The fact that one was born and came into the world is a fact or fate one receives without oneâs choice. No one can choose to be born. A free spirit is not as free as he or she might suppose.

âChild,â for Nietzsche refers to the attitude of accepting oneâs being, given as a fate, with joy. The child affirms his fate of being with joy. This affirmative attitude to life is the strength of the child. As Nietzsche puts it, the total affirmation of fate is the âlove of fate.â The child lives with a total affirmation of life; hence it is âholy yes.â The childâs selfless affirmation is âinnocent,â and âforgetfulâ of ego or self-consciousness. The child is also playful. The child transforms his or her life into joy and play. The burden of life is made lighter, so the child can fly and dance. Such Nietzschean expressions as âdancing wheel,â âgame,â and âplayâ translate his insight that âjoyfulnessâ must belong to the essence of human life.

The "Will to Power"

One of Nietzsche's central concepts is the will to power, a process of expansion and venting of creative energy that he believed was the basic driving force of nature. He believed it to be the fundamental causal power in the world, the driving force of all natural phenomena and the dynamic to which all other causal powers could be reduced. That is, Nietzsche in part hoped will to power could be a "theory of everything," providing the ultimate foundations for explanations of everything from whole societies, to individual organisms, down to mere lumps of matter. In contrast to the "theories of everything" attempted in physics, Nietzsche's was teleological in nature.

Nietzsche perhaps developed the will to power concept furthest with regard to living organisms, and it is there where the concept is perhaps easiest to understand. There, the will to power is taken as an animal's most fundamental instinct or drive, even more fundamental than the act of self-preservation; the latter is but an epiphenomenon of the former.

Physiologists should think before putting down the instinct of self-preservation as the cardinal instinct of an organic being. A living thing seeks above all to discharge its strengthâlife itself is will to power; self-preservation is only one of the indirect and most frequent results. (from Beyond Good and Evil)

The will to power is something like the desire to exert one's will in self-overcoming, although this "willing" may be unconscious. Indeed, it is unconscious in all non-human beings; it was the frustration of this will that first caused man to become conscious at all. The philosopher and art critic Arthur C. Danto says that "aggression" is at least sometimes an approximate synonym. However, Nietzsche's ideas of aggression are almost always meant as aggression toward oneself â a sublimation of the brute's aggression â as the energy a person motivates toward self-mastery. In any case, since the will to power is fundamental, any other drives are to be reduced to it; the "will to survive" (i.e. the survival instinct) that biologists (at least in Nietzsche's day) thought to be fundamental, for example, was in this light a manifestation of the will to power.

My idea is that every specific body strives to become master over all space and to extend its force (âits will to power) and to thrust back all that resists its extension. But it continually encounters similar efforts on the part of other bodies and ends by coming to an arrangement ("union") with those of them that are sufficiently related to it: thus they then conspire together for power. And the process goes on. (Beyond Good and Evil, 636, trans. Walter Kaufmann)

Not just instincts but also higher-level behaviors (even in humans) were to be reduced to the will to power. This includes such apparently harmful acts as physical violence, lying, and domination, on one hand, and such apparently non-harmful acts as gift giving, love, and praise on the other. In Beyond Good and Evil, Nietzsche claims that philosophers' "will to truth" (i.e., their apparent desire to dispassionately seek objective truth) is actually nothing more than a manifestation of their will to power; this will can be life-affirming or a manifestation of nihilism, but it is will to power all the same.

[Anything which] is a living and not a dying body... will have to be an incarnate will to power, it will strive to grow, spread, seize, become predominant â not from any morality or immorality but because it is living and because life simply is will to power... 'Exploitation'... belongs to the essence of what lives, as a basic organic function; it is a consequence of the will to power, which is after all the will to life. (Beyond Good and Evil, 259, trans. Walter Kaufmann)

As indicated above, the will to power is meant to explain more than just the behavior of an individual person or animal. The will to power can also be the explanation for why water flows as it does, why plants grow, and why various societies, enclaves, and civilizations behave as they do.

Similar ideas in others' thought

With respect to the will to power, Nietzsche was influenced early on by Arthur Schopenhauer and his concept of the "will to live", but he explicitly denied the identity of the two ideas and renounced Schopenhauer's influence in The Birth of Tragedy, (his first book) where he stated his view that Schopenhauer's ideas were pessimistic and will-negating. Philosophers have noted a parallel between the will to power and Hegel's theory of history.

Defense of the idea

Although the idea may seem harsh to some, Nietzsche saw the will to powerâor, as he famously put it, the ability to "say yes! to life"âas life-affirming. Creatures affirm the instinct in exerting their energy, in venting their strength. The suffering borne of conflict between competing wills and the efforts to overcome one's environment are not evil (âgood and evilâ for him was a false dichotomy anyway), but a part of existence to be embraced. It signifies the healthy expression of the natural order, whereas failing to act in one's self-interest is seen as a type of illness. Enduring satisfaction and pleasure result from living creatively, overcoming oneself, and successfully exerting the will to power.

Ethics

Nietzsche's work addresses ethics from several perspectives; in today's terms, we might say his remarks pertain to meta-ethics, normative ethics, and descriptive ethics.

As far as meta-ethics is concerned, Nietzsche can perhaps most usefully be classified as a moral skeptic; that is, he claims that all ethical statements are false, because any kind of correspondence between ethical statements and "moral facts" is illusory. (This is part of a more general claim that there is no universally true fact, roughly because none of them more than "appear" to correspond to reality). Instead, ethical statements (like all statements) are mere "interpretations."

Sometimes, Nietzsche may seem to have very definite opinions on what is moral or immoral. Note, however, that Nietzsche's moral opinions may be explained without attributing to him the claim that they are "true." For Nietzsche, after all, we needn't disregard a statement merely because it is false. On the contrary, he often claims that falsehood is essential for "life." Interestingly enough, he mentions a 'dishonest lie,' discussing Wagner in The Case of Wagner, as opposed to an 'honest' one, saying further, to consult Plato with regards to the latter, which should give some idea of the layers of paradox in his work.

In the juncture between normative ethics and descriptive ethics, Nietzsche distinguishes between "master morality" and "slave morality." Although he recognizes that not everyone holds either scheme in a clearly delineated fashion without some syncretism, he presents them in contrast to one another. Some of the contrasts in master vs. slave morality:

- "good" and "bad" interpretations vs. "good" and "evil" interpretations

- "aristocratic" vs. "part of the 'herd'"

- determines values independently of predetermined foundations (nature) vs. determines values on predetermined, unquestioned foundations (Christianity).

These ideas were elaborated in his book On the Genealogy of Morals, in which he also introduced the key concept of ressentiment as the basis for the slave morality.

The revolt of the slave in morals begins in the very principle of ressentiment becoming creative and giving birth to valuesâa ressentiment experienced by creatures who, deprived as they are of the proper outlet of action are forced to find their compensation in an imaginary revenge. While every aristocratic morality springs from a triumphant affirmation of its own demands, the slave morality says 'no' from the very outset to what is 'outside itself,' 'different from itself,' and 'not itself'; and this 'no' is its creative deed. (On the Genealogy of Morals)

Nietzsche's assessment of both the antiquity and resultant impediments presented by the ethical and moralistic teachings of the world's monotheistic religions eventually led him to his own epiphany about the nature of God and morality, resulting in his work Thus Spoke Zarathustra.

Eternal Recurrence of the Same

Nietzscheâs concept of the âEternal Recurrence of the Sameâ shows an interesting contrast. While Nietzsche himself was enthusiastic about it, any other philosopher has not taken it seriously. This concept arises out the tension between oneâs will and the irreversibility of time. No matter how one wills, one cannot go backward in time. Nietzsche formulates this concept as to mean that all events reoccur in the same sequence, again and again. The question is this; can you will it? According to Nietzsche, it is the ultimate form of nihilism. There are a number of interpretations of this concept, but none is beyond speculation.

Politics

During the First World War and after 1945, many regarded Nietzsche as having helped to cause the German militarism. Nietzsche was popular in Germany in the 1890s. Many Germans read Thus Spake Zarathustra and were influenced by Nietzsche's appeal of unlimited individualism and the development of a personality. The enormous popularity of Nietzsche led to the Subversion debate in German politics in 1894-1895. Conservatives wanted to ban the work of Nietzsche. Nietzsche influenced the Social-democratic revisionists, anarchists, feminists and the left-wing German youth movement.

Nietzsche became popular among National Socialists during the interbellum who appropriated fragments of his work, notably Alfred BÀumler in his reading of The Will to Power. During Nazi leadership, his work was widely studied in German schools and universities. Nazi Germany often viewed Nietzsche as one of their "founding fathers." They incorporated much of his ideology and thoughts about power into their own political philosophy (without consideration to its contextual meaning). Although there exists some significant differences between Nietzsche and Nazism, his ideas of power, weakness, women, and religion became axioms of Nazi society. The wide popularity of Nietzsche among Nazis was due partly to Nietzsche's sister, Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche, a Nazi sympathizer who edited much of Nietzsche's works.

It is worth noting that Nietzsche's thought largely stands opposed to Nazism. In particular, Nietzsche despised anti-Semitism (which partially led to his falling out with composer Richard Wagner) and nationalism. He took a dim view of German culture as it was in his time, and derided both the state and populism. As the joke goes: "Nietzsche detested Nationalism, Socialism, Germans and mass movements, so naturally he was adopted as the intellectual mascot of the National Socialist German Workers' Party." He was also far from being a racist, believing that the "vigor" of any population could only be increased by mixing with others. In The Twilight of the Idols, Nietzsche says, "...the concept of 'pure blood' is the opposite of a harmless concept."

As for the idea of the "blond beast," Walter Kaufmann has this to say in The Will to Power: "The 'blond beast' is not a racial concept and does not refer to the 'Nordic race' of which the Nazis later made so much. Nietzsche specifically refers to Arabs and Japanese, Romans and Greeks, no less than ancient Teutonic tribes when he first introduces the term... and the 'blondness' obviously refers to the beast, the lion, rather than the kind of man."

While some of his writings on "the Jewish question" were critical of the Jewish population in Europe, he also praised the strength of the Jewish people, and this criticism was equally, if not more strongly, applied to the English, the Germans, and the rest of Europe. He also valorized strong leadership, and it was this last tendency that the Nazis took up.

While his use by the Nazis was inaccurate, it should not be supposed that he was strongly liberal either. One of the things that he seems to have detested the most about Christianity was its emphasis on pity and how this leads to the elevation of the weak-minded. Nietzsche believed that it was wrong to deprive people of their pain, because it was this very pain that stirred them to improve themselves, to grow and become stronger. It would overstate the matter to say that he disbelieved in helping people; but he was persuaded that much Christian pity robbed people of necessary painful life experiences, and robbing a person of his necessary pain, for Nietzsche, was wrong. He once noted in his Ecce Homo: "pain is not an objection to life."

Nietzsche often referred to the common people who participated in mass movements and shared a common mass psychology as "the rabble," and "the herd." He valued individualism above all else. While he had a dislike of the state in general, he also spoke negatively of anarchists and made it clear that only certain individuals should attempt to break away from the herd mentality. This theme is common throughout Thus Spake Zarathustra.

Nietzsche's politics are discernible through his writings, but are difficult to access directly since he eschewed any political affiliation or label. There are some liberal tendencies in his beliefs, such as his distrust of strong punishment for criminals and even a criticism of the death penalty can be found in his early work. However, Nietzsche had much disdain for liberalism, and spent much of his writing contesting the thoughts of Immanuel Kant. Nietzsche believed that "Democracy has in all ages been the form under which organizing strength has perished," that "Liberalism [is] the transformation of mankind into cattle," and that "Modern democracy is the historic form of decay of the state"(The Antichrist).

Ironically, since World War II, Nietzsche's influence has generally been clustered on the political left, particularly in France by way of post-structuralist thought (Gilles Deleuze and Pierre Klossowski are often credited for writing the earliest monographs to draw new attention to his work, and a 1972 conference at CĂ©risy-la-Salle is similarly regarded as the most important event in France for a generation's reception of Nietzsche). However, in the United States, Nietzsche appears to have exercised some influence upon certain conservative academics (see, for example, Leo Strauss and Allan Bloom).

Themes and Trends in Nietzsche's Work

Nietzsche is important as a precursor of twentieth-century existentialism, an inspiration for post-structuralism and an influence on postmodernism.

Nietzsche's works helped to reinforce not only agnostic trends that followed Enlightenment thinkers, and the biological worldview gaining currency from the evolutionary theory of Charles Darwin (which also later found expression in the "medical" and "instinctive" interpretations of human behavior by Sigmund Freud), but also the "romantic nationalist" political movements in the late nineteenth century when various peoples of Europe began to celebrate archaeological finds and literature related to pagan ancestors, such as the uncovered Viking burial mounds in Scandinavia, Wagnerian interpretations of Norse mythology stemming from the Eddas of Iceland, Italian nationalist celebrations of the glories of a unified, pre-Christian Roman peninsula, French examination of Celtic Gaul of the pre-Roman era, and Irish nationalist interest in revitalizing the Irish language. Anthropological discoveries about India, particularly by Germany, also contributed to Nietzsche's broad religious and cultural sense.

Some people have suggested that Fyodor Dostoevsky may have specifically created the plot of his Crime and Punishment as a Christian rebuttal to Nietzsche, though this cannot be correct as Dostoevsky finished Crime and Punishment well before Nietzsche published any of his works. Nietzsche admired Dostoevsky and read several of his works in French translation. In an 1887 letter Nietzsche says that he read Notes from Underground (translated 1886) first, and two years later makes reference to a stage production of Crime and Punishment, which he calls Dostoevsky's "main novel" insofar as it followed the internal torment of its protagonist. In Twilight of the Idols, he calls Dostoevsky the only psychologist from whom he had something to learn: encountering him was "the most beautiful accident of my life, more so than even my discovery of Stendhal" (KSA 6:147).

Nietzsche and women

Nietzsche's comments on women are perceptibly impudent (although it is also the case that he attacked men for their behaviors as well). However, the women he came into contact with typically reported that he was amiable and treated their ideas with much more respect and consideration than they were generally acquainted with from educated men in that period of time, amidst various sociological circumstances that continue to this day (e.g., Feminism). Moreover, in this connection, Nietzsche was acquainted with the work On Women by Schopenhauer and was probably influenced by it to some degree. As such, some statements scattered throughout his works seem forthright to attack women in a similar vein. And, indeed, Nietzsche believed there were radical differences between the mind of men as such and the mind of women as such. "Thus," said Nietzsche through the mouth of his Zarathustra, "would I have man and woman: the one fit for warfare, the other fit for giving birth; and both fit for dancing with head and legs" (Zarathustra III. [56, "Old and New Tables," sect. 23])âthat is to say: both are capable of doing their share of humanity's work, with their respective physiological conditions granted and therewith elucidating, each individually, their potentialities. Of course, it is contentious whether Nietzsche here adequately or accurately identifies the "potentialities" of women and men.

Chronological List of Works

Writings and philosophy

- Aus meinem Leben, 1858

- Ăber Musik, 1858

- Napoleon III als Praesident, 1862

- Fatum und Geschichte, 1862

- Willensfreiheit und Fatum, 1862

- Kann der Neidische je wahrhaft glĂŒcklich sein?, 1863

- Ăber Stimmungen, 1864

- Mein Leben, 1864

- Homer und die klassische Philologie, 1868

- Ăber die Zukunft unserer Bildungsanstalten

- FĂŒnf Vorreden zu fĂŒnf ungeschriebenen BĂŒchern, 1872 comprised of:

- Ăber das Pathos der Wahrheit

- Gedanken ĂŒber die Zukunft unserer Bildungsanstalten

- Der griechische Staat

- Das VerhÀltnis der Schopenhauerischen Philosophie zu einer deutschen Cultur

- Homer's Wettkampf

- Die Geburt der Tragödie, 1872 (The Birth of Tragedy)

- Ăber Wahrheit und LĂŒge im aussermoralischen Sinn

- Die Philosophie im tragischen Zeitalter der Griechen

- UnzeitgemÀsse Betrachtungen, 1876 (The Untimely Ones) comprised of:

- David Strauss: der Bekenner und der Schriftsteller, 1873 (David Strauss: the Confessor and the Writer)

- Vom Nutzen und Nachtheil der Historie fĂŒr das Leben, 1874 (On the Use and Abuse of History for Life)

- Schopenhauer als Erzieher, 1874 (Schopenhauer as Educator)

- Richard Wagner in Bayreuth, 1876

- Menschliches, Allzumenschliches, 1878 (Human, All-Too-Human) with the two sequels:

- Vermischte Meinungen und SprĂŒche, 1879 (Mixed Opinions and Maxims)

- Der Wanderer und sein Schatten, 1879 (The Wanderer and His Shadow)

- Morgenröte, 1881 (The Dawn)

- Die fröhliche Wissenschaft, 1882 (The Gay Science)

- Also sprach Zarathustra, 1885 (Thus Spoke Zarathustra)

- Jenseits von Gut und Böse, 1886 (Beyond Good and Evil)

- Zur Genealogie der Moral, 1887 (On the Genealogy of Morals)

- Der Fall Wagner, 1888 (The Case of Wagner)

- Götzen-DÀmmerung, 1888 (Twilight of the Idols)

- Der Antichrist, 1888 (The Antichrist)

- Ecce Homo, 1888 ("Behold the man", an attempt at autobiography; the title refers to Pontius Pilate's statement upon meeting Jesus Christ and possibly to Bonaparte's upon meeting Goethe: VoilĂ un homme!)

- Nietzsche contra Wagner, 1888

- Der Wille zur Macht, 1901 (The Will to Power, a highly selective collection of notes taken from various notebooks, and put into a outline for a book which Nietzsche made but never expanded; collected by his sister after his insanity and published after his death)

Philology

- De fontibus Laertii Diogenii

- Ăber die alten hexametrischen Nomen

- Ăber die Apophthegmata und ihre Sammler

- Ăber die literarhistorischen Quellen des Suidas

- Ăber die Quellen der Lexikographen

Poetry

- Idyllen aus Messina

- Dionysos-Dithyramben, written 1888, published 1892 (Dionysus-Dithyrambs)

Music

Note: This is not a complete list. A title not dated was composed during the same year as the title preceding it. Further information for many of the below listed works may be found at this site annotated within the time of their composition.

- Allegretto, for piano, before 1858

- Hoch tut euch auf, chorus, December 1858

- Einleitung (trans: Introduction), piano duet

- Phantasie, piano duet, December 1859

- Miserere, chorus for 5 voices, summer 1860

- Einleitung (or: EntwĂŒrfe zu einem Weihnachtsoratorium), oratorio on piano, December 1861

- Huter, ist die Nacht bald hin?, chorus (in fragments)

- Presto, piano duet

- Overture for Strings (?)

- Aus der Tiefe rufe ich (?)

- String Quartet Piece (?)

- Schmerz ist der Grundton der Natur (?)

- Einleitung, orchestral overture for piano

- Mein Platz vor der Tur, NWV 1, solo voice and piano, autumn 1861

- Heldenklage, piano, 1862

- Klavierstuck, piano

- Ungarischer Marsch, piano

- Zigeunertanz, piano

- Edes titok (or: Still und ergeben), piano

- Aus der Jugendzeit, NWV 8, solo voice and piano, summer 1862

- So lach doch mal, piano, August 1862

- Da geht ein Bach, NWV 10b

- Im Mondschein auf der Puszta, piano, September 1862

- Ermanarich, piano, September 1862

- Mazurka, piano, November 1862

- Aus der Czarda, piano, November 1862

- Das zerbrochene Ringlein, NWV 14, May 1863

- Albumblatt, piano, August 1863

- Wie sich Rebenranken schwingen, NWV 16, summer 1863, voice and piano

- Nachlang einer Sylvestenacht, duet for violin and piano, January 2 1864

- Beschwörung, NWV 20

- Nachspiel, NWV 21

- StÀndchen, NWV 22

- Unendlich, NWV 23

- Verwelkt, NWV 24

- Ungewitter, NWV 25, 1864

- Gern und gerner, NWV 26

- Das Kind an die erloschene Kerze, NWV 27

- Es winkt und neigt sich, NWV 28

- Die junge Fischerin, NWV 29, voice and piano, June 1865

- O weint um sie, choir and piano, December 1865

- Herbstlich sonnige Tage, piano and 4 voices, April 1867

- Adel Ich muss nun gehen, 4 voices, August 1870

- Das "Fragment an sich", piano, October 1871

- Kirchengeschichtliches Responsorium, chorus and piano, November 1871

- Manfred-Meditation, 1872, final ver. 1877

- Monodie Ă deux (or: Lob der Barmherzigkeit), piano, February 1873

- Hymnus an die Freundschaft (trans: Hymn to Friendship; also: Festzug der Freunde zum Tempel der Freundschaft, trans: Festival of Friends at the Tempel of Friendship), piano, December 29, 1874

- Gebet an das Leben (trans: Prayer to Life), NWV 41, solo voice and piano, 1882, text by Lou Andreas-Salome

- Hymnus an das Leben (trans: Hymn to Life), chorus and orchestra, summer 1887

On Hymn to Life

Oft regarded to be idiosyncratic for a philosopher, Nietzsche accorded to his music that it played a role in the understanding of his philosophical thought. In particular, this was laden upon Hymn to Life and its circumstance is treated here in the following below. Parts of this song's melody were also used earlier in Hymn to Friendship. Friendship was conducted by Nietzsche at Bayreuth to the Wagners and, according to Cosima, had led to the first sign of a break with his friend Richard, in 1874.

Nietzsche states, after communicating the main idea of Thus Spoke Zarathustra along with an aspect of his âgaya scienza,â in Ecce Homo: ...that Hymn to Life... âa scarcely trivial symptom of my condition during that year when the Yes-saying pathos par excellence, which I call the tragic pathos, was alive in me to the highest degree. The time will come when it will be sung in my memory (Walter Kaufmann). The composition Hymn to Life was partly done by Nietzsche in August/September 1882, supported by the second stanza of the poem Lebensgebet by Lou Andreas-Salome. During 1884, Nietzsche wrote to Gast: This time, âmusicâ will reach you. I want to have a song made that could also be performed in public in order to seduce people to my philosophy.

With this request the lied (song) underwent substantial revision by âmaestro Pietro Gastiâ (Ecce Homo) to such an extent that it may be considered his own but he modestly denied all ownership. Thereafter, it was published under Nietzsche's name by E. W. Fritzsch in Leipzig as a first edition amid the summer of 1887, disregarding Hymn to Friendship. In October, Nietzsche wrote a letter to the German conductor Felix Motti, to whom he expresses about his composition Hymn to Life that which pertains to its high aesthetical import for his philosophical oeuvre: I wish that this piece of music may stand as a complement to the word of the philosopher which, in the manner of words, must remain by necessity unclear. The affect of my philosophy finds its expression in this hymn.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bataille, George. 1994. On Nietzsche. Paragon House. ISBN 1557786445

- Clark, Maudemarie. 1990. Nietzsche on Truth and Philosophy. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521348508

- Hayman, Ronald. 1980. Nietzsche: A Critical Life. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195202045

- Heidegger, Martin. 1991. Nietzsche: Volumes One and Two. Harper San Francisco.

- Heidegger, Martin. 1991. Nietzsche: Volumes Three and Four. Harper San Francisco.

- Janz, Curt Paul. 1993. Friedrich Nietzsche. Biographie. MĂŒnchen: Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag.

- Kaufmann, Walter. 1974. Nietzsche: Philosopher, Psychologist, Antichrist. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691019835

- Leiter, Brian. 2014. Nietzsche on Morality. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415856805

- Mencken, H.L. 2003. The Philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche. Sharp Press. ISBN 9781884365317

- Nehamas, Alexander. 1985. Nietzsche: Life as Literature. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674624351

- Nietzsche, Friedrich. 1986. Samtliche Briefe Kritische Studienausgabe (KSA). De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3110109634

- Richardson, John. 1996. Nietzsche's System. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195098464

- Taffel, David. 2003. Nietzche Unbound: The Struggle for Spirit in the Age of Science. Paragon House. ISBN 1557788227

- Thomas, Richard Hinton. 1983. Nietzsche in German politics and society, 1890-1918 Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0719009334

External Links

All links retrieved April 11, 2024.

- Project Gutenberg e-text Nietzsche

- Santayana's Criticism Of Nietzsche PhilosophicalSociety.com.

General Philosophy Sources

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.