Francisco Pizarro (c. 1475 â June 26, 1541) was a Spanish conquistador, conqueror of the Inca Civilization and founder of the city of Lima, the modern-day capital of Peru. Remembered by some as an adventurer and conqueror, his name is vilified in Peru where he is regarded as a criminal who destroyed a culture and brought death and tyranny to the Peruvian people.

Pizarro had been appointed governor of Peru before the country was even conqueredâtestimony to European arrogance. Hence, Atahualpa, the last Inca leader, could be accused of treason. The Incas were also surprised by Spanish tactics, which employed any meansâtorture, treachery, deceptionâto achieve their goals.

The opening of the New World gave men such as Pizarro, with limited abilities, unexpected opportunities to succeed. Their job was to conquer and to accumulate riches; they and their king believed that this was a God-given right, confirmed by papal decree. They were unable to see the value of the cultures they encountered because they did not think that anything of worth could reside within the non-Christian world.

Early Life

Pizarro was born in 1471 (other sources may differ, 1475-1478, unknown) in Trujillo (Extremadura), Spain. He was an illegitimate son of Gonzalo Pizarro, Sr., who as colonel of infantry afterwards served in Italy under Gonsalvo de Cordova, and in Navarre, with some distinction. Francisco was the eldest brother of Gonzalo Pizarro, Jr., Juan Pizarro II, and Hernando Pizarro. He was also the second cousin of Hernándo Cortés, the conquistador of Mexico.

Of Pizarro's early years hardly anything is known, but he appears to have been poorly cared for, and his education was neglected, leaving him illiterate. Shortly after the news of the discovery of the New World had reached Spain he was in Seville. He sailed to the New World in 1502, landing in the West Indies and lived on the island of Hispaniola, where he took part in various Spanish missions of exploration and conquest.

In 1510 he took part in an expedition from Hispaniola to Urab under Alonso de Ojeda, by whom he was entrusted with the charge of the unfortunate settlement at San Sebastián. In 1513, Pizarro accompanied Vasco Núñez de Balboa (whom he later helped to bring to the executioner's block) in his crossing of the Isthmus of Panama to discover the Pacific Ocean and to establish a settlement at Darién, Panama. He also received a repartimiento under Pedro Arias de Ãvila (Pedrarias), and became a cattle farmer at Panama.

Expeditions to South America

The first attempt to explore western South America was undertaken in 1522 by Pascual de Andagoya. The first native South Americans he encountered told him about a gold-rich territory called Virú which was on a river called Pirú (the vocals were later corrupted to Perú) from which they came. This is written about by the Incan writer, Garcilaso de la Vega in his Comentarios Reales.[1] Andagoya eventually established contact with several Native American curacas (chiefs), of which he later claimed among them were sorcerers and witches.

Having reached as far as the San Juan River (part of the present boundary between Ecuador and Colombia), Andagoya fell very ill and decided to return. Back in Panama, Andagoya spread the news and stories about "Birú"âa great land to the south rich with gold (the legendary El Dorado). This, along with the accounts of success of Hernán Cortés in Mexico years before, caught the immediate attention of Pizarro, prompting a new series of expeditions to the south in search of the riches of the Inca Civilization.

In 1524, while still in Panama, Pizarro entered into a partnership with a priest named Hernando de Luque and a soldier named Diego de Almagro, for purposes of exploration and conquest towards the south. Pizarro, Almagro and Luque afterwards renewed their compact in a more solemn and explicit manner, agreeing to conquer and divide equally among themselves the opulent empire they hoped to reach. Pizarro would command the expedition, Almagro would provide the military and food supplies, and Luque would be in charge of the finances and any further provisions needed; they finally agreed to call their enterprise, the "Empresa del Levante." Historians agree the whole accord of the expeditions among the three was done verbally, since no written document exists to prove otherwise.

First expedition (1524)

On September 13, 1524, the first of three expeditions left from Panama for the conquest of Peru with about 80 men and four horses. Diego de Almagro was left behind to recruit more men and gather more supplies with the intent of soon joining Pizarro. The governor of Panama, Pedro Arias Dávila, at first himself approved of the intent of exploring South America. This first expedition, however, turned out to be utterly unsuccessful, as the conquistadors led by Pizarro sailed down the Pacific and reached no farther than Colombia, where they only encountered various hardships such as bad weather, lack of food and skirmishes with hostile natives, causing Almagro to lose an eye by an arrow-shot. Moreover, the names the Spanish used for the spots they reached only suggest the uncomfortable situation they faced along the way: Puerto Deseado (desired port), Puerto del Hambre (port of hunger) and Puerto Quemado (burned port), off the coast of Colombia. Fearing subsequent hostile encounters like the Battle of Punta Quemada, Pizarro chose to end his first tentative expedition and returned, without any luck, to Panama.

Second expedition (1526)

Two years after the first unsuccessful expedition, Pizarro, Almagro, and Luque started the arrangements for a second expedition with permission from Pedro Arias Dávila. The governor, who himself was preparing an expedition north to Nicaragua, was reluctant to approve of another expedition to the south. The three associates, however, eventually won his trust, and he acquiesced. Also by this time, a new governor, Pedro de los RÃos, was due to take office in Panama and had initially manifested his approval of expeditions to the south.

In August 1526, after all preparations were ready, the second long expedition left Panama with two ships with 160 men and several horses, reaching the San Juan River and much further south than the first time. Soon after arriving the party separated, with Pizarro staying to explore the new and often perilous territory off the swampy Colombian coasts, while the expedition's second-in-command, Almagro, was sent back to Panama for reinforcements. Pizarro's Piloto Mayor (main pilot), Bartolomé Ruiz, continued sailing south and, after crossing the equator, found and captured a balsa raft of natives from Tumbes who were supervising the area. To everyone's surprise, these carried a load of textiles, ceramic objects, and some much-desired pieces of gold, silver, and emeralds, making Ruiz's findings the central focus of this second expedition which only served to pique the conquistadors' interests for more gold and land. Some of the natives were also taken aboard Ruiz's ship to serve later as interpreters.

He then set sail north for the San Juan River, arriving to find Pizarro and his men exhausted from the serious difficulties they had faced exploring the new territory. Soon Almagro also sailed into the port with his vessel laden with supplies, and a considerable reinforcement of at least 80 recruited men who had arrived at Panama from Spain with the same expeditionary spirit. The findings and excellent news from Ruiz along with Almagro's new reinforcements cheered Pizarro and his tired followers. They then decided to sail back to the territory already explored by Ruiz and, after a difficult voyage due to strong winds and currents, reached Atacames in the Ecuadorian coast. Here they found a very large native population recently brought under Inca rule. Unfortunately for the conquistadors, the warlike spirit of the people they had just encountered seemed so defiant and dangerous in numbers that the Spanish decided not to enter the land.

The Thirteen of the fame

After much wrangling between Pizarro and Almagro, it was decided that Pizarro would stay at a safer place, the Isla de Gallo, near the coast, while Almagro would return yet again to Panama with Luque for more reinforcementsâthis time with proof of the gold they had just found and the news of the discovery of an obvious wealthy land they had just explored. Pedro de los Rios, the new governor, after hearing the news that various men had fallen sick and others died in unknown lands, outright rejected Almagro's application for a third expedition in 1527. In addition, he ordered two ships commanded by Juan Tafur to be sent immediately with the intention of bringing Pizarro and everyone back to Panama. The leader of the expedition had no intention of returning, and when Tafur arrived at the now famous Isla de Gallo, Pizarro drew a line in the sand, saying:

Here lies Peru with its riches; Here, Panama and its poverty. Choose, each man, what best becomes a brave Castilian."

Only 13 men decided to stay with Pizarro and later became known as âthe thirteen of the fameâ ("Los trece de la fama"), while the rest of the expedition left with Tafur aboard his ships. Ruiz also left in one of the ships with the intention of joining Almagro and Luque in their efforts to gather more reinforcements and eventually return to aid Pizarro.

Soon after the ships left, the 13 men and Pizarro constructed a crude boat and left nine miles north for La Isla Gorgona, where they would remain for seven months before the arrival of new provisions. Back in Panama, Pedro de los Rios (after much convincing by Luque) had finally acquiesced to the requests for another ship, but only to bring Pizarro back within six months and completely abandon the expedition. Both Almagro and Luque quickly grasped the opportunity and left Panama (this time without new recruits) for la Isla Gorgona to once again join Pizarro. On meeting with Pizarro, the associates decided to continue sailing south on the recommendations of Ruiz's Indian interpreters.

By April 1528, they finally reached the coast of Tumbes, officially on Peruvian soil. Tumbes became the territory of the first fruits of success the Spanish had so long desired, as they were received with a warm welcome of hospitality and provisions from the Tumpis, the local inhabitants. On subsequent days two of Pizarro's men reconnoitered the territory and both, on separate accounts, reported back the incredible riches of the land, including the decorations of silver and gold around the chief's residence and the hospitable attentions with which they were received by everyone. The Spanish also saw, for the first time, the Peruvian llama, which Pizarro called the "little camels."

The natives also began calling the Spanish the "Children of the Sun" due to their fair complexion and brilliant armor. Pizarro, meanwhile, continued receiving the same accounts of a powerful monarch who ruled over the land they were exploring. These events only served as evidence to convince the expedition of the wealth and power displayed at Tumbes as an example of the riches the Peruvian territory had awaiting to conquer. The conquistadors decided to return to Panama to prepare the final expedition of conquest with more recruits and provisions. Before leaving, however, Pizarro and his followers sailed south not so far along the coast to see if anything of interest could be found. Historian William H. Prescott recounts that after passing through territories they named such as Cape Blanco, port of Payta, Sechura, Punta de Aguja, Santa Cruz, and Trujillo, Peru (founded by Almagro years later), they finally reached for the first time the ninth degree of the southern latitude in South America. On their return towards Panama, Pizarro briefly stopped at Tumbes, where two of his men had decided to stay to learn the customs and language of the natives. Pizarro was also offered a native or two himself, one of which was later baptized as Felipillo and served as an important interpreter, the equivalent of Cortés' La Malinche of Mexico.

Their final stop was at La Isla Gorgona, where two of his ill men (one had died) had stayed before. After at least 18 months away, Pizarro and his followers anchored off the coasts of Panama to prepare for the last and final expedition.

Return to Spain and interview with Charles V (Capitulación de Toledo, 1529)

When the new governor of Panama, Pedro de los RÃos, had refused to allow for a third expedition to the south, the associates resolved for Pizarro to leave for Spain and apply to the sovereign in person. Pizarro sailed from Panama for Spain in the spring of 1528, reaching Seville in early summer. Charles V, who was at Toledo, Spain, had an interview with Pizarro, was presented with precious Incan textiles and embroideries, and heard of his expeditions in South America, a territory the conquistador described as very rich in gold and silver which he and his followers had bravely explored "to extend the empire of Castile."

The king, who was soon to leave for Italy, was impressed at the accounts of Pizarro and promised to give his support for the conquest of Peru. It would be Isabella of Portugal (1503-1539), however, who, in the absence of the king, would sign the famous Capitulación de Toledo, a document which authorized Francisco Pizarro to proceed with the conquest of Peru. Pizarro was officially named the governor, captain general, and the "Adelantado" of the New Castile for the distance of two hundred leagues along the newly discovered coast, and invested with all the authority and prerogatives of a viceroy, his associates being left in wholly secondary positions (a fact which later incensed Almagro and would lead to eventual discords with Pizarro).

One of the conditions of the grant was that within six months Pizarro should raise a sufficiently equipped force of 250 men, of whom one hundred might be drawn from the colonies. This gave Pizarro time to leave for his native Trujillo and convince his brother Hernando Pizarro and other close friends to join him on his third expedition. Along with him also came Francisco de Orellana, who would later discover and explore the entire length of the Amazon River. Two more of his brothers, Juan Pizarro II and Gonzalo Pizarro, would later decide to also join him.

When the expedition was ready and left the following year, it numbered three ships, 180 men, and 27 horses. Since Pizarro could not meet the number of men the Capitulación had required, he sailed clandestinely from the port of Sanlúcar de Barrameda for the La Gomera in the Canary Islands in January 1530. He was there to be joined by his brother Hernando and the remaining men in two vessels that would sail back to Panama. Pizarro's third and final expedition left Panama for Peru on December 27, 1530.

Conquest of Peru (1532)

In 1532, Pizarro once again landed in the coasts near Ecuador, where some gold, silver, and emeralds were procured and then dispatched to Almagro, who had stayed in Panama to gather more recruits. Though Pizarro's main objective was to then set sail and dock at Tumbes like his previous expedition, he was forced to confront the Punian natives in the Battle of Puná, leaving three Spaniards dead and four hundred dead or wounded natives. Diseases like smallpox had been brought from Europe, afflicting the local populations and Europeans alike.

Soon after, Hernando de Soto, another conquistador that had joined the expedition, arrived to aid Pizarro and with him sailed towards Tumbes, only to find the place deserted and destroyed, their two fellow conquistadors expected there had disappeared or died under murky circumstances. The chiefs explained the fierce tribes of Punians had attacked them and ransacked the place. As Tumbes no longer afforded the safe accommodations Pizarro sought, he decided to lead an excursion into the interior of the land and in July 1532 established the first Spanish settlement in Peru (the third in South America after Santa Marta, Colombia, in 1526), calling it San Miguel de Piura. The first repartimiento in Peru was established here. After these events, de Soto was dispatched to explore the new lands and, after various days away, returned with an envoy from Atahualpa the Inca emperor himself and a few presents with an invitation for a meeting with the Spaniards.

The Inca were involved in a civil war between two rulers vying for the seat of the Inca Empire when the Spanish arrived in 1532.[2] The Spanish took advantage of the disruption caused by this in-fighting, and formed alliances with enemies of the Inca. Superior weaponry, new-formed alliances with enemies of the Inca, and Old World diseases like smallpox, allowed the Spanish to conquer the vast Inca Empire, which was estimated to have an army of 40,000.

Following the defeat of his brother, Huascar, Atahualpa was resting in the Sierra of northern Peru, near Cajamarca, in the nearby thermal baths known today as the Baños del Inca. After marching for almost two months towards Cajamarca, Pizarro and his force of just 180 soldiers and 27 horses arrived and initiated proceedings for a meeting with Atahualpa. Pizarro sent de Soto, friar Vicente de Valverde and native interpreter Felipillo to approach Atahualpa at Cajamarca's central plaza. Atahualpa, however, refused the Spanish presence in his land by saying he would "be no man's tributary," which led Pizarro and his force to attack Atahualpa's army in what became the Battle of Cajamarca on November 16, 1532.[3]

The Spanish were successful and Pizarro executed Atahualpa's 12-man honor guard and took the Inca captive at the so-called ransom room. Despite fulfilling his promise of filling one room with gold and two with silver, Atahualpa was convicted of killing his brother and plotting against Pizarro and his forces, and was executed by garrote on August 29, 1533. Though this was likely the case, it is apparent that Pizzaro wished to find a reason for executing Atahualpa without angering the people he was attempting to subdue.

A year later, Pizarro invaded Cuzco with indigenous troops and with it sealed the conquest of Peru. During the exploration of Cuzco, Pizarro was impressed and through his officers wrote back to Charles V, saying:

This city is the greatest and the finest ever seen in this country or anywhere in the Indiesâ¦. We can assure your Majesty that it is so beautiful and has such fine buildings that it would be remarkable even in Spain.

After the Spanish had sealed the conquest of Peru by taking Cusco in 1533, Jauja in the fertile Mantaro Valley was established as Peru's provisional capital in April 1534, but it was too far up in the mountains and far from the sea to serve as the Spanish capital of Peru. Pizarro thus founded the city of Lima, named la Ciudad de los Reyes (the City of Kings), in Peru's central coast on January 18, 1535, a foundation that he considered one of the most important things he had created in life.

After the final effort of the Inca to recover Cusco had been defeated by Diego de Almagro, a dispute occurred between him and Pizarro respecting the limits of their jurisdiction. This led to confrontations between the Pizarro brothers and Almagro, who was eventually defeated during the Battle of Las Salinas (1538) and executed. The followers of Almagro (including his son), offended by the arrogant conduct of Pizarro and his followers after the defeat and execution of Almagro, organized a conspiracy which ended in Pizarro's assassination at his palace in Lima on June 26, 1541.

Death

Pizarro left behind his mestizo children with their mother, Inés Huaillas Yupanqui, daughter of Atahualpa and granddaughter of Huayna Capac, who gave birth to Gonzalo (legitimized in 1537 and died when he was 14); by the same woman, a daughter, Francisca. After Pizarro's death, Inés married a Spanish cavalier named Ampuero and left for Spain, taking her daughter who would later be legitimized by imperial decree.

Francisca eventually married her uncle, Hernando Pizarro, in Spain, on October 10, 1537. A third son of Pizarro, Francisco, by a relative of Atahualpa, who was never legitimized, died shortly after reaching Spain.[4]

Legacy

Historians have often compared Pizarro and Cortés' conquests in North and South America as very similar in style and career. Both used alliances with enemy civilizations to achieve their conquests. Pizarro, however, faced the Incas with a smaller army and fewer resources than Cortés and at a much greater distance from the Spanish Caribbean outposts that could easily support him. Thus, some rank Pizarro slightly ahead of Cortés in their battles for conquest.

Though Pizarro is well known in Peru for being the leader behind the Spanish conquest of the Inca Civilization, a growing number of Peruvians regard him as a kind of criminal. He is vilified for having ordered Atahualpa's death despite his paid ransom of filling a room with gold and two with silver, which was later split among all of Pizarro's closest associates.

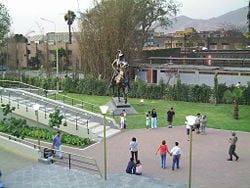

In the early 1930s, sculptor Ramsey MacDonald created three copies of an anonymous European foot soldier resembling a conquistador with a helmet, wielding a sword and riding a horse. The first copy was offered to Mexico to represent Hernán Cortés, though it was rejected. Since the Spanish conquerors had the same appearance with helmet and beard, the statue was taken to Lima in 1934. The other two copies of the statue reside in Wisconsin and in Trujillo, Spain.

In 2003, after years of lobbying by indigenous and mixed-raced majority requesting for the equestrian statue of Pizarro to be removed, the mayor of Lima, Luis Castañeda Lossio, approved the transfer of the statue to another location: an adjacent square to the country's government palace. Since 2004, however, Pizarro's statue has been placed in a rehabilitated park surrounded by the recently restored seventeenth-century pre-Hispanic murals in the RÃmac District. The statue faces the RÃmac River and the government palace.

See Also

Notes

- â Frances G. Crowley, Garcilaso de la Vega, el Inca and his sources in Comentarios reales de los incas (Mouton, 1971).

- â Terence N. D'Altroy, The Incas (Blackwell Publishing, 2003, ISBN 978-1405116763), 216.

- â Encounter at Cajamarca. Retrieved May 11, 2015.

- â William Prescott, History of the Conquest of Peru. (London, 1889), online chap. 28. worldwideschool.org. (Seattle, WA: World Wide School, 1999). Retrieved June 25, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Crowley, Frances G. Garcilaso de la Vega, el Inca and his sources in Comentarios reales de los incas. (Studies in Spanish literature) Mouton, 1971. ASIN B0006CF9JE

- D'Altroy, Terence N. The Incas. Blackwell Publishing, 2003. ISBN 978-1405116763

- DeAngelis, Gina. Francisco Pizarro and the Conquest of the Inca. Philadelphia, PA: Chelsea House, 2000. ISBN 0613325842

- Hemming, John. Conquest of the Incas. New York, NY: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 2003 (original 1973). ISBN 0156028263

- Prescott, William H. History of the Conquest of Peru. Philadelphia, PA: J. B. Lippincott & Co., 1883. Reprint, Barnes and Noble, 2004. ISBN 978-0486440071

External links

All links retrieved April 9, 2024.

- Franciso Pizarro â Catholic Encyclopedia

- Pizarro and the Conquest of the Incas â PBS Special: Conquistadors

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.