Steve McQueen

| Steve McQueen | |

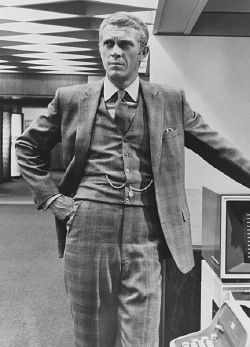

McQueen in The Thomas Crown Affair (1968)

| |

| Born | Terrence Stephen McQueen[1]

[2] March 24 1930 Beech Grove, Indiana, U.S. |

|---|---|

| Died | November 7 1980 (aged 50) Ciudad Juárez, Mexico |

| Occupation | Actor |

| Years active | 1952‚Äď1980 |

| Spouse(s) | Neile Adams‚Äč (m.¬†1956; div.¬†1972)‚Äč Ali MacGraw‚Äč (m.¬†1980) |

| Children | 2, including Chad McQueen |

| Relatives | Steven R. McQueen (grandson) |

| Website stevemcqueen.com | |

Terrence Stephen McQueen (March 24, 1930 - November 7, 1980) was an American actor. His antihero persona, emphasized during the height of the counterculture of the 1960s, made him a top box-office draw for his films of the late 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s. He was nicknamed the "King of Cool."

McQueen received an Academy Award nomination for his role in The Sand Pebbles (1966). His other popular films include Love With the Proper Stranger (1963), The Cincinnati Kid (1965), Nevada Smith (1966), The Thomas Crown Affair (1968), Bullitt (1968), Le Mans (1971), The Getaway (1972), and Papillon (1973). In addition, he starred in the all-star ensemble films The Magnificent Seven (1960), The Great Escape (1963), and The Towering Inferno (1974).

In 1974, McQueen became the highest-paid movie star in the world, although he did not act in a film for another four years, instead spending his time on his passion - racing cars and motorcycles. Despite being known as a "bad boy," in his later years McQueen converted to Christianity. Shortly before his death from a heart attack following surgery to remove cancerous tumors, McQueen met with Billy Graham who presented him with his personal Bible.

Life

Terrence Stephen McQueen was born to a single mother on March 24, 1930, at St. Francis Hospital in Beech Grove, Indiana, a suburb of Indianapolis. McQueen, of Scottish descent, was raised a Roman Catholic. His parents never married. McQueen's father, William McQueen, a stunt pilot for a barnstorming flying circus, left his mother, Julia Ann (a.k.a. Julianne) Crawford, six months after meeting her.[3][4] Several biographers have stated that his mother Julia Ann was an alcoholic.[5][6][7][8] Unable to cope with caring for a small child, she left the boy with her parents (Victor and Lillian) in Slater, Missouri, in 1933. As the Great Depression worsened, McQueen and his grandparents moved in with Lillian's brother Claude and his family at their farm in Slater McQueen later said that he had good memories of living on the farm, noting that his great-uncle Claude "was a very good man, very strong, very fair. I learned a lot from him."[3]

Claude gave McQueen a red tricycle on his fourth birthday, a gift that McQueen subsequently credited with sparking his early interest in car racing.[3] McQueen's mother, Julia, married when the boy was eight and she brought him from the farm to live with her and her new husband in Indianapolis. His great-uncle Claude gave McQueen a special gift at his departure. "The day I left the farm," he recalled, "Uncle Claude gave me a personal going-away present‚ÄĒa gold pocket watch, with an inscription inside the case." The inscription read "To Steve¬†‚Äď who has been a son to me."[7]

Dyslexic and partially deaf due to a childhood ear infection,[3] McQueen did not adjust well to school or his new life. His stepfather beat him to such an extent that at the age of nine he left home to live on the streets.[6] He later recalled "When a kid doesn't have any love when he's small, he begins to wonder if he's good enough. My mother didn't love me, and I didn't have a father. I thought, 'Well, I must not be very good.'"[4] Soon he was running with a street gang and committing acts of petty crime. Unable to control his behavior, his mother sent him back to her grandparents and great-uncle in Slater.

When McQueen was 12, Julia wrote to her uncle Claude, asking that her son be returned to her again to live in Los Angeles, California, where she lived with her second husband. By McQueen's own account, he and his new stepfather "locked horns immediately."[3] As McQueen began to rebel again, he was sent back to live with Claude for a final time. At age 14, he left Claude's farm without saying goodbye and joined a circus for a short time.[3] He drifted back to his mother and stepfather in Los Angeles‚ÄĒresuming his life as a gang member and petty criminal.[4] He was caught stealing hubcaps by the police and handed over to his stepfather, who beat him severely and threw the youth down a flight of stairs. McQueen looked up at his stepfather and said, "You lay your stinking hands on me again and I swear, I'll kill you."[3]

After this incident, McQueen's stepfather persuaded his mother to sign a court order stating that McQueen was incorrigible, remanding him to the California Junior Boys Republic in Chino.[3] Here, McQueen began to change and mature. He was not popular with the other boys at first:

"Say the boys had a chance once a month to load into a bus and go into town to see a movie. And they lost out because one guy in the bungalow didn't get his work done right. Well, you can pretty well guess they're gonna have something to say about that. I paid my dues with the other fellows quite a few times. I got my lumps, no doubt about it. The other guys in the bungalow had ways of paying you back for interfering with their well-being."[9]

McQueen gradually became a role model and was elected to the Boys Council, a group who set the rules and regulations governing the boys' lives.[3] He left the Boys Republic at age 16. After he became famous as an actor, he regularly returned to talk to the resident boys and retained a lifelong association with the center.[10]

At age 16, McQueen returned to live with his mother, who had moved to Greenwich Village in New York City. There he met two sailors from the Merchant Marine and decided to sign on to a ship bound for the Dominican Republic.[3] Once there, he abandoned his new post, eventually being employed in a brothel.[6] Later McQueen made his way to Texas and drifted from job to job, including selling pens at a traveling carnival, and working as a lumberjack in Canada. He was arrested for vagrancy in the Deep South and served a 30-day assignment on a chain gang.[4]

Military service

In 1947, after receiving permission from his mother (since he was not yet 18 years old), McQueen enlisted in the United States Marine Corps. He was sent to Parris Island for boot camp.[2][11] He was promoted to private first class and assigned to an armored unit.[3] He initially struggled with conforming to the discipline of the service, and was demoted to private seven times. He took an unauthorized absence, going UA by failing to return after a weekend pass expired. He was caught by the shore patrol while staying with a girlfriend (Barbara Ross) for two weeks. After resisting arrest, he was sentenced to 41 days in the brig.[3]

After this, McQueen resolved to focus his energies on self-improvement and embraced the Marines' discipline. He saved the lives of five other Marines during an Arctic exercise, pulling them from a tank before it broke through ice into the sea.[3] He was assigned to the honor guard responsible for guarding the presidential yacht of US President Harry Truman.[3] McQueen served until 1950, when he was honorably discharged.[2][11] He later said he had enjoyed his time in the Marines.[10] He remembered this period with the Marines as a formative time in his life, saying, "The Marines made a man out of me. I learned how to get along with others, and I had a platform to jump off of."[4]

Relationships and friendships

On November 2, 1956, he married Filipino actress and dancer Neile Adams, with whom he had a daughter, Terry Leslie (June 5, 1959 ‚Äď March 19, 1998) and a son, Chad (born December 28, 1960).[4] McQueen and Adams divorced in 1972. In her autobiography, My Husband, My Friend, Adams stated that she had an abortion in 1971, when their marriage was on the rocks.[8] One of McQueen's four grandchildren is actor Steven R. McQueen (who is best known for playing Jeremy Gilbert in The Vampire Diaries and Jimmy Borelli in Chicago Fire).

According to photographer William Claxton, McQueen smoked marijuana almost every day; biographer Marc Eliot stated that McQueen used a large amount of cocaine in the early 1970s.[6] He was also a heavy cigarette smoker. McQueen sometimes drank to excess; he was arrested for driving while intoxicated in Anchorage, Alaska, in 1972.[12]

McQueen had a number of affairs, and then in 1973 he married actress Ali MacGraw, his co-star in The Getaway. However, both struggled with addiction and the marriage ended in a divorce in 1978.[13] MacGraw suffered a miscarriage during their marriage.[14] Some friends later claimed that MacGraw was the one true love of McQueen's life: "He was madly in love with her until the day he died."[13]

McQueen, as well as a number of other actors, took lessons in martial arts from Bruce Lee. Along with James Coburn, Bruce's brother Robert Lee, Peter Chin, Dan Inosanto, and Taky Kimura, he served as pallbearer at Bruce Lee's funeral.[15]

After discovering a mutual interest in racing, McQueen and Great Escape co-star James Garner became good friends and lived near each other. McQueen recalled:

I could see that Jim was neat around his place. Flowers trimmed, no papers in the yard... grass always cut. So to piss him off, I'd start lobbing empty beer cans down the hill into his driveway. He'd have his drive all spick 'n' span when he left the house, then get home to find all these empty cans. Took him a long time to figure out it was me.[7]

On January 16, 1980, less than a year before his death, McQueen married model Barbara Minty. In her book Steve McQueen: The Last Mile, Barbara wrote of McQueen becoming an Evangelical Christian toward the end of his life.[16] This was due in part to the influences of his flying instructor, Sammy Mason, Mason's son Pete, and Barbara herself. McQueen attended his local church, Ventura Missionary Church, and was visited by evangelist Billy Graham shortly before his death. The pair prayed together and talked about the afterlife. Graham left McQueen his personal Bible, which became his most valued possession. When McQueen died he was found clutching that Bible.[17]

Illness and death

McQueen developed a persistent cough in 1978. He gave up cigarettes and underwent antibiotic treatments without improvement. His shortness of breath grew more pronounced, and on December 22, 1979, after filming The Hunter, a biopsy revealed pleural mesothelioma,[18] a cancer associated with asbestos exposure for which there is no known cure.

A few months later, McQueen gave a medical interview in which he blamed his condition on asbestos exposure. McQueen believed that asbestos used in movie sound stage insulation and race-drivers protective suits and helmets could have been involved, but he thought it more likely that his illness was a direct result of massive exposure while removing asbestos lagging (insulation) from pipes aboard a troop ship while he served in the Marines.[5][19]

By February 1980, evidence of widespread metastasis was found. He tried to keep the condition a secret but on March 11, 1980, the National Enquirer disclosed that he had "terminal cancer."[20] In July 1980, McQueen traveled to Rosarito Beach, Mexico, for unconventional treatment after U.S. doctors told him they could do nothing to prolong his life.[18] Controversy arose over the trip because McQueen sought treatment from William Donald Kelley, who was promoting a variation of the Gerson therapy that used coffee enemas, frequent washing with shampoos, daily injections of fluid containing live cells from cattle and sheep, massages, and laetrile, a reputed anti-cancer drug available in Mexico, but long known to be both toxic and ineffective at treating cancer. Kelley's dental license, his only medically related license (until revoked in 1976) had been for orthodontics, a field of dentistry, not medicine.[21]

McQueen returned to the U.S. in early October. Despite metastasis of the cancer throughout McQueen's body, Kelley publicly announced that McQueen would be completely cured and return to normal life. McQueen's condition soon worsened and huge tumors developed in his abdomen.[21]

In late October 1980, McQueen flew to Ciudad Ju√°rez, Chihuahua, Mexico to have an abdominal tumor on his liver (weighing around 5 lbs) removed, despite warnings from his U.S. doctors that the tumor was inoperable and his heart could not withstand the surgery.[7][21] Using the name "Samuel Sheppard," McQueen checked into a small Ju√°rez clinic where the doctors and staff were unaware of his actual identity.[22]

On November 7, 1980, Steve McQueen died of a heart attack at 3:45 a.m. at a Ju√°rez hospital, 12 hours after surgery to remove or reduce numerous metastatic tumors in his neck and abdomen.[7] He was 50 years old.

Leonard DeWitt of the Ventura Missionary Church presided over McQueen's memorial service.[16] McQueen was cremated, and his ashes were spread in the Pacific Ocean.

Acting career

1950s and 1960s

In 1952, with financial assistance under the G.I. Bill, McQueen began studying acting in New York at Sanford Meisner's Neighborhood Playhouse and at HB Studio under Uta Hagen.[3] He reportedly delivered his first dialogue on a theatre stage in a 1952 play produced by Yiddish theatre star Molly Picon. McQueen's character spoke one brief line: "Alts iz farloyrn." ("All is lost."). During this time, he also studied acting with Stella Adler, in whose class he met Gia Scala. He and Gia dated from 1952 to 1954.[23]

Long enamored of cars and motorcycles, McQueen began to earn money by competing in weekend motorcycle races at Long Island City Raceway. He purchased the first two of many motorcycles, a Harley-Davidson and a Triumph.[4] He soon became an excellent racer, winning about $100 each weekend (equivalent to $1,000 in 2021).[3]

McQueen had minor roles in stage productions, including Peg o' My Heart, The Member of the Wedding, and Two Fingers of Pride. He made his Broadway debut in 1955 in the play A Hatful of Rain, starring Ben Gazzara.

In late 1955 at the age of 25, McQueen left New York and headed for Los Angeles, and sought acting jobs in Hollywood. When McQueen appeared in a two-part Westinghouse Studio One television presentation entitled The Defenders, Hollywood manager Hilly Elkins took note of him[8] and decided that B-movies would be a good place for the young actor to make his mark. McQueen's first role was a bit part in Somebody Up There Likes Me (1956), directed by Robert Wise and starring Paul Newman. McQueen was subsequently hired for the films Never Love a Stranger; The Blob (his first leading role, science fiction); and The Great St. Louis Bank Robbery (1959).

McQueen's first breakout role came on television. He appeared on Dale Robertson's NBC western series Tales of Wells Fargo as Bill Longley. Elkins, then McQueen's manager, successfully lobbied Vincent M. Fennelly, producer of the western series Trackdown, to have McQueen read for the part of bounty hunter Josh Randall. He first appeared in Season 1 Episode 21 of Trackdown in 1958. He appeared as Randall in that episode, cast opposite series lead Robert Culp, a former New York motorcycle racing buddy. McQueen appeared again on Trackdown in Episode 31 of the first season, in which he played twin brothers, one of whom was an outlaw sought by Culp's character, Hoby Gilman.

McQueen next filmed a pilot episode for what became the series titled Wanted: Dead or Alive, which aired on CBS in September 1958. This became his breakout role, becoming a household name as a result of this series.[3] The generally negative image of the bounty hunter as the antihero infused with mystery and detachment made this show stand out from the typical TV Western. The 94 episodes that ran from 1958 until early 1961 kept McQueen steadily employed, and he became a fixture at the renowned Iverson Movie Ranch in Chatsworth, where much of the outdoor action for Wanted: Dead or Alive was shot.

At 29, McQueen got a significant break when Frank Sinatra removed Sammy Davis Jr. from the film Never So Few after Davis supposedly made some mildly negative remarks about Sinatra in a radio interview, and Davis's role went to McQueen. Sinatra saw something special in McQueen and ensured that the young actor got plenty of closeups in a role that earned McQueen favorable reviews. McQueen's character, Bill Ringa, was never more comfortable than when driving at high speed‚ÄĒin this case in a jeep‚ÄĒor handling a switchblade or a tommy gun.

After Never So Few, the film's director John Sturges cast McQueen in his next movie, promising to "give him the camera." The Magnificent Seven (1960), in which he played Vin Tanner and co-starred with Yul Brynner, Eli Wallach, Robert Vaughn, Charles Bronson, Horst Buchholz, and James Coburn, became McQueen's first major hit and led to his withdrawal from Wanted: Dead or Alive. McQueen's focused portrayal of the taciturn second lead catapulted his career. His added touches in many of the shots (such as shaking a shotgun round before loading it, repeatedly checking his gun while in the background of a shot, and wiping his hat rim) annoyed costar Brynner, who protested that McQueen was trying to steal scenes.[3] In his autobiography, Eli Wallach reports struggling to conceal his amusement while watching the filming of the funeral-procession scene where Brynner's and McQueen's characters first meet: Brynner was furious at McQueen's shotgun-round-shake, which effectively diverted the viewer's attention to McQueen.[24]

McQueen played the top-billed lead role in the next big Sturges film, 1963's The Great Escape, Hollywood's fictional depiction of the true story of a historic mass escape from a World War II POW camp, Stalag Luft III. Insurance concerns prevented McQueen from performing the film's notable motorcycle leap, which was done by his friend and fellow cycle enthusiast Bud Ekins, who resembled McQueen from a distance. When Johnny Carson later tried to congratulate McQueen for the jump during a broadcast of The Tonight Show, McQueen said, "It wasn't me. That was Bud Ekins." This film established McQueen's box-office clout and secured his status as a superstar.[25]

Also in 1963, McQueen starred in Love with the Proper Stranger with Natalie Wood. He later appeared as the titular Nevada Smith, a character from Harold Robbins's novel The Carpetbaggers portrayed by Alan Ladd two years earlier in a movie version of that novel. Nevada Smith was an enormously successful Western action adventure prequel that also featured Karl Malden and Suzanne Pleshette. After starring in 1965's The Cincinnati Kid as a poker player, McQueen earned his only Academy Award nomination in 1966 for his role as an engine-room sailor in The Sand Pebbles, in which he starred opposite Candice Bergen and Richard Attenborough, whom he had previously worked with in The Great Escape.[7]

He followed his Oscar nomination with 1968's Bullitt, one of his best-known films, and his personal favorite, which co-starred Jacqueline Bisset, Robert Vaughn, and Don Gordon. It featured an unprecedented (and endlessly imitated) car chase through San Francisco. Although McQueen did the driving that appeared in closeup, this was about 10 percent of what is seen in the film's car chase. The rest of the driving by McQueen's character was done by stunt drivers Bud Ekins and Loren Janes.[26] Bullitt went so far over budget that Warner Brothers cancelled the contract on the rest of his films, seven in all.

When Bullitt became a huge box-office success, Warner Brothers tried to woo him back, but he refused, and his next film was made with an independent studio and released by United Artists. For this film, McQueen went for a change of image, playing a debonair role as a wealthy executive in The Thomas Crown Affair with Faye Dunaway in 1968. The following year, he made the southern period piece The Reivers.

1970s

In 1971, McQueen starred in the poorly received auto-racing drama Le Mans, followed by Junior Bonner in 1972, a story of an aging rodeo rider. He worked for director Sam Peckinpah again with the leading role in The Getaway, where he met future wife Ali MacGraw. He followed this with a physically demanding role as a Devil's Island prisoner in 1973's Papillon, featuring Dustin Hoffman as his character's tragic sidekick.

By the time of The Getaway, McQueen was the world's highest-paid actor.[27] After 1974's The Towering Inferno, co-starring with his long-time professional rival Paul Newman and reuniting him with Dunaway, became a tremendous box-office success, McQueen all but disappeared from the public eye. He focused on motorcycle racing and traveling around the country in a motor home and on his vintage Indian motorcycles. He did not return to acting until 1978 with An Enemy of the People, playing against type as a bearded, bespectacled 19th-century doctor in this adaptation of a Henrik Ibsen play. The film was never properly released theatrically, but has appeared occasionally on PBS.

His last two films were loosely based on true stories: Tom Horn, a Western adventure about a former Army scout-turned professional gunman who worked for the big cattle ranchers hunting down rustlers, and later hanged for murder in the shooting death of a sheepherder, and The Hunter, an urban action movie about a modern-day bounty hunter, both released in 1980.

Stunts, motor racing and flying

McQueen was an avid motorcycle and race car enthusiast. When he had the opportunity to drive in a movie, he performed many of his own stunts, including some of the car chases in Bullitt and the motorcycle chase in The Great Escape.[4] Although the jump over the fence in The Great Escape was done by Bud Ekins for insurance purposes, McQueen did have considerable screen time riding his 650 cc Triumph TR6 Trophy motorcycle. It was difficult to find riders as skilled as McQueen. At one point, using editing, McQueen is seen in a German uniform chasing himself on another bike.

McQueen and John Sturges planned to make Day of the Champion,[8] a movie about Formula One racing, but McQueen was busy with the delayed The Sand Pebbles. They had a contract with the German N√ľrburgring, and after John Frankenheimer shot scenes there for Grand Prix, the reels were turned over to Sturges. Frankenheimer was ahead in schedule, and the McQueen-Sturges project was called off.

McQueen considered being a professional race car driver. He had a one-off outing in the British Touring Car Championship in 1961, driving a BMC Mini at Brands Hatch, finishing third. In the 1970 12 Hours of Sebring race, Peter Revson and McQueen (driving with a cast on his left foot from a motorcycle accident two weeks earlier) won with a Porsche 908/02 in the three-litre class and missed winning overall by 21.1 seconds to Mario Andretti/Ignazio Giunti/Nino Vaccarella in a five-litre Ferrari 512S. This same Porsche 908 was entered by his production company Solar Productions as a camera car for Le Mans in the 1970 24 Hours of Le Mans later that year. McQueen wanted to drive a Porsche 917 with Jackie Stewart in that race, but the film backers threatened to pull their support if he did. Faced with the choice of driving for 24 hours in the race or driving for the entire summer making the film, McQueen opted for the latter.[28]

McQueen competed in off-road motorcycle racing, frequently running a BSA Hornet and using alias Harvey Mushman. He was also set to co-drive in a Triumph 2500 PI for the British Leyland team in the 1970 London-Mexico rally, but had to turn it down due to movie commitments.[7]

He was inducted in the Off-road Motorsports Hall of Fame in 1978. In 1971, McQueen's Solar Productions funded the classic motorcycle documentary On Any Sunday, in which McQueen is featured, along with racing legends Mert Lawwill and Malcolm Smith. The same year, he also appeared on the cover of Sports Illustrated magazine riding a Husqvarna dirt bike.

McQueen designed a motorsports bucket seat, for which a patent was issued in 1971.[28]

By testimony of McQueen's son, Chad, Steve owned around 100 classic motorcycles, as well as around 100 exotics and vintage cars,[28] including:

- Porsche 917, Porsche 908, and Ferrari 512 race cars from the Le Mans film

- Porsche 911S (used in the opening sequence of the Le Mans film)

- 1963 Ferrari 250 GT Berlinetta Lusso

- 1967 Ferrari 275GTB/4

- 1956 Jaguar XKSS (right-hand drive) (now on exhibit at the Petersen Automotive Museum in Los Angeles, California)

- 1958 Porsche 356 Speedster 1600 Super (black exterior, interior and top) (McQueen drove the car in numerous SCCA racing events) (now in property of his son Chad)

- 1968 Ford GT40 (Gulf liveried) (used in the Le Mans film)

- 1953 Siata 208s (McQueen replaced the Siata badges with Ferrari badges and called it his "little Ferrari")[29]

- 1967 Mini Cooper-S (McQueen had the car customized by Lee Brown with changes including a single foglight, a wood dash, a recessed antenna and a custom brown paint job)

- 1951 Chevrolet Styline De Lux Convertible (used in The Hunter, McQueen bought the car in 1979 after filming ended)

- 1952 Chevrolet 3800 pickup camper conversion (McQueen used the truck for cross-country camping trips. It was the last car he rode in before his death)

- 1950 Hudson Commodore convertible

- 1952 Hudson Wasp 2-door sedan

- 1953 Hudson Hornet 4-door Sedan

- 1956 GMC Suburban

- 1958 GMC Pickup Truck (Reportedly one of McQueen's favorite cars, it is powered by a 336 Ci V8 which has been modified. The tag "MQ3188" is a reference to the ID number assigned to him when he was in reform school)[30]

- 1931 Lincoln Club Sedan

- 1963 Lincoln Continental Sedan

- 1935 Chrysler Airflow Imperial Sedan

- 1967 Rolls-Royce Silver Shadow 2-door he drove in The Thomas Crown Affair.[30]

- 1969 Chevrolet Baja Hickey race truck (originally debuted at the 1968 Mexican 1000 Rally and was driven by Cliff Coleman, Johnny Diaz, Mickey Thompson and others during its racing career; said to be the first truck specifically constructed by GM for use in the Mexican 1000; McQueen bought it from General Motors in 1970).

In spite of numerous attempts, McQueen was never able to purchase the Ford Mustang GT 390 he drove in Bullitt, which featured a modified drivetrain that suited McQueen's driving style.

McQueen also flew and owned, among other aircraft, a 1945 Stearman, tail number N3188, (his student number in reform school), a 1946 Piper J-3 Cub, and an award-winning 1931 Pitcairn PA-8 biplane, flown in the US Mail Service by famed World War I flying ace Eddie Rickenbacker. They were hangared at Santa Paula Airport an hour northwest of Hollywood, where he lived his final days.[7]

Legacy

Still known as ‚ÄúThe King of Cool‚ÄĚ decades after his death, Forbes reported McQueen as one of the highest-earning dead celebrities.[31]

On March 16, 2010, the Beech Grove, Indiana, Public Library formally dedicated the Steve McQueen Birthplace Collection to commemorate the 80th anniversary of McQueen's birth on March 24, 1930.[32]

Steve McQueen: The Man & Le Mans, a 2015 documentary, examines the actor's quest to create and star in the 1971 auto-racing film Le Mans. His son Chad McQueen and former wife Neile Adams are among those interviewed.

On September 28, 2017, there was a selected showing in some theaters of his life story and spiritual quest, Steve McQueen ‚Äď American Icon. There was an encore presentation on October 10, 2017. The film received mostly positive reviews. Kenneth R. Morefield of Christianity Today said it "offers a timeless reminder that even those among us living the most celebrated lives often long for the peace and sense of purpose that only God can provide."[33] Michael Foust of Wordslingers called it "one of the most powerful and inspiring documentaries I've ever seen."[34]

In the 2019 Quentin Tarantino film Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, McQueen is portrayed by Damian Lewis.

The Academy Film Archive houses the Steve McQueen-Neile Adams Collection, which consists of personal prints and home movies.[35] The archive has preserved several of McQueen's home movies.[36]

Ford commercials

In 1998, director Paul Street created a commercial for the Ford Puma. Footage was shot in modern-day San Francisco, set to the theme music from Bullitt. Archive footage of McQueen was used to digitally superimpose him driving and exiting the car in settings reminiscent of the film. The Puma shares the same number plate of the classic fastback Mustang used in Bullitt, and as he parks in the garage (next to the Mustang), he pauses and looks meaningfully at a motorcycle tucked in the corner, similar to that used in The Great Escape.[37]

At the Detroit Auto Show in January 2018, Ford unveiled the new 2019 Mustang Bullitt. The company called on McQueen's granddaughter, actress Molly McQueen, to make the announcement. After a brief rundown of the tribute car's particulars, a short film was shown in which Molly was introduced to the actual Bullitt Mustang, a 1968 Mustang Fastback with a 390 cubic-inch engine and a four-speed manual gearbox. That car has been in possession of the same family since 1974 and hidden away from the public until then, when it was driven out from under the press stand and up the center aisle of Ford's booth to much fanfare.[38]

Memorabilia

- Motorcycles and cars

Except for three motorcycles sold with other memorabilia in 2006,[39] most of McQueen's collection of 130 motorcycles was sold four years after his death.

From 1995 to 2011, McQueen's red 1957 fuel-injected Chevrolet convertible was displayed at the Petersen Automotive Museum in Los Angeles in a special Cars of Steve McQueen exhibit. It is now in the collection of actress Ruth Buzzi and her husband Kent Perkins. McQueen's British racing green 1956 Jaguar XKSS is located in the Petersen Automotive Museum and is in derivable condition, having been driven by Jay Leno in an episode of Jay Leno's Garage. In August 2019, Mecum Auctions announced it would auction the Bullitt Mustang Hero Car at its Kissimmee auction, held January 2‚Äď12, 2020.[40] The car sold without reserve for $3.4¬†million ($3.74¬†million after commissions and fees).

- Watches

The Rolex Explorer II, Reference 1655, known as Rolex Steve McQueen in the horology collectors' world, the Rolex Submariner, Reference 5512, which McQueen was often photographed wearing in private moments, sold for $234,000 at auction on June 11, 2009, a world-record price for the type.

McQueen was a sponsored ambassador for Heuer watches. In the 1971 film Le Mans, he famously wore a blue-faced Monaco Ref. 1133, which led to its cult status among watch collectors, purchasing six watches of the same model for the shoot of the film. On December 12, 2020, one of the last six models sold and one of two held in private hands was sold for a record US$2.208 million at a Phillips auction in New York City, becoming the most expensive Heuer watch sold at auction.[41] Tag Heuer continues to promote its Monaco range with McQueen's image.[42]

Among McQueen's other watches was a Hanhart 417 chronograph. McQueen was known to wear this watch often when he was riding his motorcycle.[43]

- Sunglasses

The blue-tinted sunglasses (Persol 714) worn by McQueen in the 1968 movie The Thomas Crown Affair sold at a Bonhams auction in Los Angeles for $70,200 in 2006.[44]

Awards and honors

McQueen starred in more than 30 movies and was nominated for a best actor Academy Award for his role in 1966’s The Sand Pebbles. He also competed in various car and motorcycle races, and was inducted into the Off-road Motorsports Hall of Fame in 1978.[45]

- (1967) Nominated ‚Äď Best Actor in a Leading Role in The Sand Pebbles

- (1964) Nominated ‚Äď Best Actor ‚Äď Motion Picture Drama in Love with the Proper Stranger

- (1967) Nominated ‚Äď Best Actor ‚Äď Motion Picture Drama in The Sand Pebbles

- (1970) Nominated ‚Äď Best Actor ‚Äď Motion Picture Musical or Comedy in The Reivers

- (1974) Nominated ‚Äď Best Actor ‚Äď Motion Picture Drama in Papillon

- Moscow International Film Festival

- (1963) ‚Äď Won ‚Äď Best Actor in The Great Escape[46]

He also received a number of posthumous honors. In November 1999, McQueen was inducted into the Motorcycle Hall of Fame. He was credited with contributions including financing the film On Any Sunday, supporting a team of off-road riders, and enhancing the public image of motorcycling overall.[47]

McQueen was inducted into the Hall of Great Western Performers in April 2007 in a ceremony at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum.[48]

In 2012, McQueen was honored with the Warren Zevon Tribute Award by the Asbestos Disease Awareness Organization (ADAO).[49]

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ Everett Aaker, Television Western Players, 1960-1975: A Biographical Dictionary (McFarland & Company, 2017, ISBN 978-1476662503).

- ‚ÜĎ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Greg Laurie, Steve McQueen: The Salvation of an American Icon (American Icon Press, 2017, ISBN 978-1946891051).

- ‚ÜĎ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 3.17 Marshall Terrill, Steve McQueen: Portrait of an American Rebel (Plexus Publishing, 2001, ISBN 978-0859652315).

- ‚ÜĎ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 Marshall Terrill, Steve McQueen: In His Own Words (Dalton Watson, 2020, ISBN 1854432710).

- ‚ÜĎ 5.0 5.1 Penina Spiegel, McQueen: The Untold Story of a Bad Boy in Hollywood (Doubleday, 1986, ISBN 0385193920).

- ‚ÜĎ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Marc Eliot, Steve McQueen: A Biography (Crown Publishing, 2011, ISBN 978-0307453211).

- ‚ÜĎ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 William F. Nolan, McQueen (Congdon & Weed Inc., 1984, ISBN 978-0312925260).

- ‚ÜĎ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Neile McQueen Toffel, My Husband, My Friend (Atheneum, 1986, ISBN 978-0689116377).

- ‚ÜĎ Malachy McCoy, Steve McQueen: The Unauthorized Biography (H. Regnery Co, 1974, ISBN 978-0809290567).

- ‚ÜĎ 10.0 10.1 Wes D. Gehring, Steve McQueen: The Great Escape (Indiana Historical Society Press, 2009, ISBN 978-0871952790).

- ‚ÜĎ 11.0 11.1 Dwight Jon Zimmerman, The Life Steve McQueen (Motorbooks, 2017, ISBN 978-0760358115).

- ‚ÜĎ Steve McQueen, arrested in Anchorage, Alaska in 1972 The First Steve McQueen Site. Retrieved November 25, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ 13.0 13.1 Zachary, Steve McQueen's Last Love Remembers Their Stormy Hollywood Romance Shared, July 4, 2018. Retrieved November 23, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ Ali MacGraw, Moving Pictures: An Autobiography (Bantam, 1991, ISBN 978-0553072709).

- ‚ÜĎ Alyssa Burrows, Lee, Bruce¬†(1940-1973) History Link, October 21, 2002. Retrieved November 25, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ 16.0 16.1 Barbara McQueen, Steve McQueen: The Last Mile (Dalton Watson, 2012, ISBN 978-1854432551).

- ‚ÜĎ The Moment Steve McQueen‚Äôs Life Changed Billy Graham Evangelistic Association, September 26, 2017. Retrieved November 25, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ 18.0 18.1 Barron H. Lerner, When Illness Goes Public (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006, ISBN 978-0801884627).

- ‚ÜĎ Christopher Sandford, McQueen: The Biography (Taylor Trade Publishing, 2003, ISBN 978-0878333073).

- ‚ÜĎ Kathy Merlock Jackson, Lisa Lyon Payne, and Kathy Shepherd Stolley, The Intersection of Star Culture in America and International Medical Tourism: Celebrity Treatment (Lexington Books, 2015, ISBN 978-0739186879).

- ‚ÜĎ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Roger Worthington, A Candid Interview with Barbara McQueen 26 Years After Mesothelioma Claimed the Life of Husband and Hollywood Icon, Steve McQueen Worthington & Caron, October 27, 2006. Retrieved November 25, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ Marcelo Abeal, Steve McQueen: The race of his life (Editorial Dunken, 2015, ISBN 978-9870280781).

- ‚ÜĎ Sterling Saint James, Gia Scala: The First Gia (Parhelion House, 2015, ISBN 978-0989369510).

- ‚ÜĎ Eli Wallach, The Good, the Bad, and Me: In My Anecdotage (Harcourt, 2005, ISBN 978-0151011896).

- ‚ÜĎ Leonard Maltin, Leonard Maltin's Family Film Guide (Signet, 1999, ISBN 978-0451197146).

- ‚ÜĎ Marc Myers, Chasing the Ghosts of 'Bullitt' The Wall Street Journal, January 26, 2011. Retrieved November 25, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ Ralph Sonny Barger, Ridin' High, Livin' Free: Hell-Raising Motorcycle Stories (Harper Perennial, 2003, ISBN 978-0060006037).

- ‚ÜĎ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Matt Stone and Chad McQueen, McQueen's Machines: The Cars and Bikes of a Hollywood Icon (Motorbooks, 2010, ISBN 978-0760338957).

- ‚ÜĎ Justin Hyde, The car that made Steve McQueen a Ferrari poser Jalopnik, August 19, 2011. Retrieved November 25, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ 30.0 30.1 Alex Nunez, Buy Steve McQueen's '58 GMC truck Autoblog, November 6, 2006. Retrieved November 25, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ Top-Earning Dead Celebrities Forbes, October 29, 2007. Retrieved November 25, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ The Steve McQueen Birthplace Collection The Steve McQueen Site. Retrieved November 26, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ Kenneth R. MorefieldThe King of Cool's Conversion Story Christianity Today, September 29, 2017.

- ‚ÜĎ Michael Foust, REVIEW: Steve McQueen's faith explored in powerful new documentary Word Slingers, September 15, 2017. Retrieved November 26, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ Steve McQueen-Neile Adams Collection Academy Film Archive. Retrieved November 26, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ Preserved Projects - Steve McQueen Academy Film Archive. Retrieved November 26, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ Ford Puma 'Steve McQueen' Directed by Paul Street YouTube. Retrieved November 26, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ Kyle Hyatt, 2019 Ford Mustang Bullitt rocks Detroit with Molly McQueen Cnet, January 14, 2018. Retrieved November 26, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ The Steve McQueen Sale and Collectors' Motorcycles & Memorabilia Bonhams, November 11, 2006. Retrieved November 26, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ Mecum Unveils Bullitt Mustang Hero Car to be Auctioned at Kissimmee 2020 Mecum Auctions, August 14, 2019. Retrieved November 26, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ Jon Bues, Steve McQueen's Monaco From 'Le Mans' Brings Home $2,208,000 At Phillips, Setting New Heuer Record Hodinkee, December 12, 2020. Retrieved November 26, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ Tag Heuer Monaco: A Timeless Emblem of Rebellious Style Tag Heuer. Retrieved November 26, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ Eric Wind, The Story Of The Hanhart 417 Chronograph: Steve McQueen's Other, Other Watch Hodinkee, November 28, 2011. Retrieved November 26, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ McQueen's shades sell for ¬£36,000 BBC, November 12, 2006. Retrieved November 26, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ Richard Crouse, The Legacy of Steve McQueen Wheels, May 2, 2021. Retrieved November 25, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ Moscow International Film Festival: 1963 Awards IMDb. Retrieved November 25, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ Steve McQueen AMA Motorcycle Hall of Fame. Retrieved November 26, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ Steve McQueen honored at Western awards USA Today, April 23, 2007. Retrieved November 26, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ Actor Steve McQueen, Beloved Husband of Barbara McQueen, Honored Posthumously with the Warren Zevon ‚ÄúKeep Me in Your Heart‚ÄĚ Memorial Tribute Award Business Wire, January 12, 2012. Retrieved November 26, 2022.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Aaker, Everett. Television Western Players, 1960-1975: A Biographical Dictionary. McFarland & Company, 2017. ISBN 978-1476662503

- Abeal, Marcelo. Steve McQueen: The race of his life. Editorial Dunken, 2015. ISBN 978-9870280781

- Barger, Ralph Sonny. Ridin' High, Livin' Free: Hell-Raising Motorcycle Stories. Harper Perennial, 2003. ISBN 978-0060006037

- Eliot, Marc. Steve McQueen: A Biography. Crown Publishing, 2011. ISBN 978-0307453211

- Gehring, Wes D. Steve McQueen: The Great Escape. Indiana Historical Society Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0871952790

- Jackson, Kathy Merlock, Lisa Lyon Payne, and Kathy Shepherd Stolley. The Intersection of Star Culture in America and International Medical Tourism: Celebrity Treatment. Lexington Books, 2015. ISBN 978-0739186879

- Laurie, Greg. Steve McQueen: The Salvation of an American Icon. American Icon Press, 2017. ISBN 978-1946891051

- Lerner, Barron H. When Illness Goes Public. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0801884627

- MacGraw, Ali. Moving Pictures: An Autobiography. Bantam, 1991. ISBN 978-0553072709

- McCoy, Malachy. Steve McQueen: The Unauthorized Biography. H. Regnery Co, 1974. ISBN 978-0809290567

- McQueen, Barbara. Steve McQueen: The Last Mile. Dalton Watson, 2012 (original 2007). ISBN 978-1854432551

- McQueen Toffel, Neile. My Husband, My Friend. Atheneum, 1986. ISBN 978-0689116377

- Maltin, Leonard. Leonard Maltin's Family Film Guide. Signet, 1999. ISBN 978-0451197146

- Nolan, William F. McQueen. Congdon & Weed Inc., 1984. ISBN 978-0312925260

- Saint James, Sterling. Gia Scala: The First Gia. Parhelion House, 2015. ISBN 978-0989369510

- Sandford, Christopher. McQueen: The Biography. Taylor Trade Publishing, 2003. ISBN 978-0878333073

- Spiegel, Penina. McQueen: The Untold Story of a Bad Boy in Hollywood. Doubleday, 1986. ISBN 0385193920

- Stone, Matt, and Chad McQueen. McQueen's Machines: The Cars and Bikes of a Hollywood Icon. Motorbooks, 2010. ISBN 978-0760338957

- Terrill, Marshall. Steve McQueen: In His Own Words. Dalton Watson, 2020. ISBN 1854432710

- Terrill, Marshall. Steve McQueen: Portrait of an American Rebel. Plexus Publishing, 2001. ISBN 978-0859652315

- Wallach, Eli. The Good, the Bad, and Me: In My Anecdotage. Harcourt, 2005. ISBN 978-0151011896

- Zimmerman, Dwight Jon. The Life Steve McQueen. Motorbooks, 2017. ISBN 978-0760358115

External links

All links retrieved February 25, 2023.

- Steve McQueen IMDb

- Steve McQueen Turner Classic Movies

- Steve McQueen (1930 - 1980) Virtual History

- Bell System Film "Family Affair" AT&T Tech Channel

- A reflection on Steve McQueen at the Iverson Movie Ranch, in "Wanted: Dead or Alive" The Iverson Movie Ranch

- Steve McQueen Find a Grave

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.