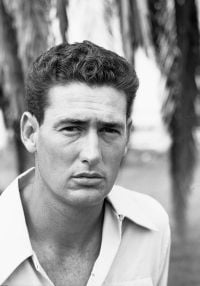

Ted Williams

Theodore Samuel Williams (August 30, 1918 â July 5, 2002), known as Ted Williams and nicknamed The Kid, the Splendid Splinter, and Teddy Ballgame, was a Major League Baseball player who played 19 seasons, twice interrupted by military service as a Marine Corps pilot, with the Boston Red Sox.

Williams was a two-time American League Most Valuable Player (MVP) winner, led the league in batting six times, and won the Triple Crown twice. He had a career batting average of .344, with 521 home runs, and was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1966. In his Hall of Fame induction speech he publicly called for the inclusion of Negro League players into the hall, an act considered instrumental in the recognition of many great players previously kept out of the Hall because of their race.

Williams is the last player in Major League Baseball to bat over .400 in a single season (.406 in 1941). He has the highest career batting average of anyone with 500 or more home runs. Yet his statistics would certainly have been higher had he not served, during the heart of his career, almost five years in the military during World War II and the Korean War.

After his playing days ended, Williams won manager of the year for running the Washington Senators' expansion team to their only winning season (86â76) in 1969. An avid fisherman after retirement, he hosted a popular television show about sport fishing.

Early life

Williams was born in San Diego, California, as Teddy Samuel Williams, after his father Samuel Williams and Teddy Roosevelt. At some point, the name and date of birth on his birth certificate was changed to Theodore, but his mother and his closest friends always called him Teddy. His father, Samuel, was a soldier, sheriff, and photographer from New York, who greatly admired the late president. His mother, May, was a Salvation Army worker of Basque descent, whose parents came from Mexico.

Williams played high school baseball at Herbert Hoover High School in San Diego and lived in the North Park area of the city. After graduation, he turned professional and had minor league stints for his hometown San Diego Padres (PCL) and the Minneapolis Millers.

Early in his career, he stated that he wished to be remembered as the "greatest hitter who ever lived," an honor that he achieved in the eyes of many by the end of his career.

Major League career

Williams moved up to the Major League Boston Red Sox in 1939, immediately making an impact as he led the American League in RBIs and finished fourth in [MLB Most Valuable Player Award|MVP]] balloting. In 1941, he entered the last day of the season with a batting average of .39955. This would have been rounded up to .400, making him the first man to hit .400 since Bill Terry in 1930. His manager left the decision whether to play up to him. Williams opted to play in both games of the day's doubleheader and risk losing his record. He got six hits in eight at bats, raising his season average to .406; no one has reached .400 since. (Williams also hit .400 in 1952 and .407 in 1953, both partial seasons.)

At the time, this achievement was overshadowed by Joe DiMaggio's 56-game hitting streak in the same season. Their rivalry was played up by the press; Williams always felt himself slightly better as a hitter, but acknowledged that DiMaggio was the better all-around player. Also in 1941, Williams set a Major League record for on-base percentage in a season at .551. That record would last until 2002, when Barry Bonds upped this mark to .582. A lesser-known accomplishment is Williams' feat of reaching base for the most consecutive games, 84. In addition, Williams holds the third- and fourth-longest such streaks. In 1957, Williams reached base in 16 consecutive plate appearances, also a Major League record.

One of Williams' other memorable accomplishments was his game-winning home run off Rip Sewell's notorious "Eephus pitch" during the 1946 All-Star Game. Archival footage shows a delighted Williams hopping around the bases, clapping; he later said this was his greatest thrill in baseball.

Among the few blemishes on Williams' playing record was his performance in his lone post-season appearance, the 1946 World Series. Williams managed just five singles in 25 at-bats, with just 1 RBI, as the Red Sox lost to the St. Louis Cardinals in the eighth inning of the seventh game. Much of this was due to his stubborn insistence to hit into the Cardinals' defensive shift, which frequently involved five or six of the Cardinals' fielders positioned to the right of second base. Williams may also have been playing with an elbow that he injured during a pre-World Series exhibition game, while the Cardinals and Brooklyn Dodgers were playing a best-of-three series to determine the National League champion.

An obsessive student of batting, Williams hit for both power and average. In 1970, he wrote a book on the subject, The Science of Hitting (revised 1986), which is still read by many baseball players. He lacked foot speed, as attested by his career total of only 24 stolen bases, one inside-the-park home run, and one occasion of hitting for the cycle.

Despite Williams's lack of fielding range, he was considered a sure fielder with a good throwing arm.

Military service

Williams served as a United States Marine Corps pilot during World War II and the Korean War. During World War II he served as a flight instructor at Naval Air Station Pensacola teaching young pilots to fly the F4U Corsair. He finished the war in Hawaii and was released from active duty in January 1946; however he did remain in the reserves

In 1952, at the age of 34, he was recalled to active duty for service in the Korean War. After getting checked out on the new F9F Panther at Marine Corps Air Station Cherry Point, North Carolina, he was assigned to VMF-311, Marine Aircraft Group 33 (MAG-33) in Korea.

On February 16, 1953, Williams was part of a 35-plane strike package against a tank and infantry training school just south of Pyongyang, North Korea. During the mission a piece of flak knocked out his hydraulics and electrical systems causing Williams to have to crash-land his fighter jet. After scrambling out of the jet he made the comment, "I ran faster than Mickey Mantle." For bringing the plane back he was also awarded the Air Medal.

Williams eventually flew 38 combat missions before being pulled from flight status in June 1953, after an old ear infection acted up. During the war he also served in the same unit as John Glenn. While these absences, which took almost five years out of the heart of a great career, significantly limited his career totals, he never complained about the time devoted to military service.

Summary of career

Williams' two MVP Awards and two Triple Crowns came in four different years. Along with Rogers Hornsby, he is one of only two players to win the Triple Crown twice, but he did not win the MVP award in either of his Triple Crown seasons. Williams, Lou Gehrig, and Chuck Klein are the only players since the establishment of the MVP award to win the Triple Crown and not be named league MVP in that season.

Williams was known as a strong pull hitter. His hitting was so feared that opponents frequently employed the radical, defensive "Williams Shift" against him, leaving only one fielder on the third-base half of the field. Rather than bunting the ball into the open space, the proud Williams batted as usual against the contrived defense. The defensive tactic is still used to this day, and is appropriately called the infield shift.

Williams retired from the game in 1960 and hit a home run in his final at-bat, on September 28, 1960, in front of only 10,454 fans at Fenway Park. This home run, a solo shot hit off Baltimore pitcher Jack Fisher in the eighth inning that reduced the Orioles' lead to 4-3 was immortalized in the New Yorker essay âHub Fans Bid Kid Adieu,â by John Updike.[1]

Hall of Fame induction speech

In his Baseball Hall of Fame induction speech in 1966, Williams included a statement calling for the recognition of the great Negro Leagues players Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson, who were not given the opportunity to play in the Major Leagues before Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in 1947. This powerful statement made by one of the game's greatest players was instrumental in the Hall of Fame eventually inducting Negro League players, beginning with Paige in 1971.

Career ranking

At the time of his retirement, Williams ranked third all-time in home runs (behind Babe Ruth and Jimmie Foxx), seventh in RBIs (after Ruth, Cap Anson, Lou Gehrig, Ty Cobb, Foxx, and Mel Ott; Stan Musial would pass Williams in 1962), and seventh in batting average (behind Cobb, Rogers Hornsby, Shoeless Joe Jackson, Lefty O'Doul, Ed Delahanty and Tris Speaker). His career batting average is the highest of any player who played his entire career in the post-1920 live-ball era. Williams was also second to Ruth in career slugging percentage, where he remains today, and first in on-base percentage. He was also second to Ruth in career walks, but has since dropped to fourth place behind Barry Bonds and Rickey Henderson. Williams remains the career leader in walks per plate appearance.

Retirement

After retirement from play, Williams served as manager of the Washington Senators, continuing with the team when they became the Texas Rangers after the 1971 season. Williams's best season as a manager was 1969 when he led the expansion Senators to an 86â76 record in their only winning season in Washington. He was chosen manager of the year after that season. Like many great players, Williams became impatient with ordinary athletes' abilities and attitudes, and his managerial career was short and largely unsuccessful. Before and after leaving Texas, he occasionally appeared at Red Sox spring training as a guest hitting instructor.

He was much more successful in fishing. An avid and expert fly fisherman and deep-sea fisherman, he spent many summers after baseball fishing the Miramichi River in New Brunswick, Canada. Williams was named to the International Game Fish Association Hall of Fame in 2000. Some opined that Williams was a rare individual who might have been the best in the world in three different disciplines: baseball hitter, fighter jet pilot, and fly fisherman. Shortly after Williams' death, conservative pundit Steve Sailer called him "possibly the most technically proficient American of the twentieth century, as his mastery of three highly different callings demonstrates."[2]

Williams reached an extensive deal with Sears, lending his name and talent toward marketing, developing, and endorsing a line of in-house sports equipmentâspecifically fishing, hunting, and baseball equipment. He was also extensively involved in the Jimmy Fund, ironically later losing a brother to leukemia, and spent much of his spare time, effort, and money in support of the cancer organization.

In his later years, Williams became a fixture at autograph shows and card shows after his son (by his third wife), John Henry Williams, took control of his career, becoming his de facto manager. The younger Williams provided structure to his father's business affairs, and rationed his father's public appearances and memorabilia signings to maximize their earnings. Although many felt that Ted was being used by his son, there is no real evidence that the younger Williams was doing anything illicit or unsavory with his father's earnings.

One of Ted Williams' final, and most memorable, public appearances was at the 1999 All-Star Game in Boston. Able to walk only a short distance, Williams was brought to the pitcher's mound in a golf cart. He proudly waved his cap to the crowdâa gesture he had never done as a player. Fans responded with a standing ovation that lasted several minutes. At the pitcher's mound he was surrounded by players from both teams, and spoke with several. Among them was fellow San Diegan Tony Gwynn, a hitter often compared to Williams, who starred with the Major League edition of the San Diego Padres.

Later in the year, he was among the members of the Major League Baseball All-Century Team introduced to the crowd at Turner Field in Atlanta prior to Game 2 of the World Series. He had also been ranked that year as number eight on the Sporting News list of the 100 Greatest Baseball Players, where he was the highest-ranking left fielder.

In his last years, Williams suffered from poor health, specifically cardiac problems. He had a pacemaker installed in November 2000 and underwent open-heart surgery in January 2001. After suffering a series of strokes and congestive heart failures, he died of cardiac arrest in Crystal River, Florida, on July 5, 2002.

Post-death

A public dispute over the disposition of Williams' body was waged after his death. Announcing there would be no funeral, his son John Henry Williams had Ted's body flown to the Alcor Life Extension Foundation in Scottsdale, Arizona, and placed in cryonic suspension. Barbara Joyce Ferrell, Ted's daughter by his first wife, sued, saying his will stated that he wanted to be cremated. John Henry's lawyer then produced an informal "family pact" signed by Ted, John Henry, and Ted's daughter Claudia, in which they agreed "to be put into biostasis after we die."

In Ted Williams: The Biography of An American Hero, author Leigh Montville makes the case that the supposed family cryonics pact was merely a practice Ted Williams autograph on a plain piece of paper, around which the "agreement" had later been hand-printed. The pact document was signed "Ted Williams," the same as his autographs, whereas he would always sign his legal documents "Theodore Williams." However, Claudia Williams testified to the authenticity of the document in a sworn affidavit.

Career Statistics

| G | AB | R | H | 2B | 3B | HR | RBI | SB | CS | BB | SO | BA | OBP | SLG |

| 2,292 | 7,706 | 1,798 | 2,654 | 525 | 71 | 521 | 1,839 | 24 | 17 | 2,019 | 709 | .344 | .482 | .634 |

Notes

- â John Updike, "Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu," New Yorker, October 22, 1960. Found at Baseball Almanac. Retrieved May 23, 2007.

- â Steve Sailer, Web Exclusives Archive: July 2002. Retrieved May 23, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Montville, Leigh. Ted Williams: The Biography of an American Hero. Broadway, 2005. ISBN 978-0767913201

- Nowlin, Bill. Ted Williams at War. Rounder Books, 2006. ISBN 978-1579401252

- Williams, Ted, and John Underwood. Science of Hitting. Fireside, 1986. ISBN 978-0671621032

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.