Encyclopedia, Difference between revisions of "John Lewis" - New World

(Redirected page to John Lewis (pianist)) Tag: New redirect |

(Removed redirect to John Lewis (pianist)) Tag: Removed redirect |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | # | + | {{epname}} |

| + | {{Infobox officeholder | ||

| + | | name = John Lewis | ||

| + | | image = John Lewis-2006 (cropped).jpg | ||

| + | | state = [[Georgia (U.S. state)|Georgia]] | ||

| + | | district = {{ushr|GA|5|5th}} | ||

| + | | term_start = January 3, 1987 | ||

| + | | term_end = July 17, 2020 | ||

| + | | predecessor = [[Wyche Fowler]] | ||

| + | | successor = ''Vacant'' | ||

| + | | office1 = Member of the [[Atlanta City Council]] from At-Large Post 18 | ||

| + | | term_start1 = January 1, 1982 | ||

| + | | term_end1 = September 3, 1985 | ||

| + | | predecessor1 = | ||

| + | | successor1 = Morris Finley | ||

| + | | office2 = 3rd Chairman of the [[Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee]] | ||

| + | | term_start2 = June 1963 | ||

| + | | term_end2 = May 1966 | ||

| + | | predecessor2 = [[Charles McDew]] | ||

| + | | successor2 = [[Stokely Carmichael]] | ||

| + | | birth_name = John Robert Lewis | ||

| + | | birth_date = {{birth date|1940|2|21}} | ||

| + | | birth_place = [[Troy, Alabama]], U.S. | ||

| + | | death_date = {{death date and age|2020|7|17|1940|2|21}} | ||

| + | | death_cause = [[Pancreatic cancer]] | ||

| + | | death_place = [[Atlanta]], Georgia, U.S. | ||

| + | | resting_place = [[South-View Cemetery]] <br/> [[Atlanta, Georgia]] | ||

| + | | party = [[Democratic Party (United States)|Democratic]] | ||

| + | | spouse = {{marriage|Lillian Miles|1968|2012|end=died}} | ||

| + | | children = 1 | ||

| + | | education = {{ubl|[[American Baptist College]] ([[Bachelor of Arts|BA]])|[[Fisk University]] ([[Bachelor of Arts|BA]])}} | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | '''John Robert Lewis''' (February 21, 1940{{spnd}}July 17, 2020) was an American statesman and [[Civil rights movement|civil-rights]] leader who served in the [[United States House of Representatives]] for {{ushr|GA|5}} from 1987 until his death in 2020. Lewis served as the chairman of the [[Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee]] ([[Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee|SNCC]]) from 1963 to 1966. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Lewis was one of the "[[Big Six (activists)|Big Six]]" leaders of groups who organized the 1963 [[March on Washington]]. He fulfilled many critical roles in the [[civil rights movement]] and its actions to end legalized [[racial segregation in the United States]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A member of the [[Democratic Party (United States)|Democratic Party]], Lewis was first elected to Congress in 1986 and served 17 terms in the [[U.S. House of Representatives]]. Due to his length of service, he became the dean of the [[United States congressional delegations from Georgia|Georgia congressional delegation]]. The district he represented included most of [[Atlanta]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | He was a leader of the Democratic Party in the U.S. House of Representatives, serving from 1991 as a [[Chief Deputy Whips of the United States House of Representatives|Chief Deputy Whip]] and from 2003 as [[Senior Chief Deputy Whip]]. Lewis received many honorary degrees and awards, including the [[Presidential Medal of Freedom]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Early life and education == | ||

| + | John Robert Lewis was born on February 21, 1940, just outside [[Troy, Alabama|Troy]], [[Alabama]], the third of ten children of Willie Mae (née Carter) and Eddie Lewis.<ref name="fid1">Stated on ''[[Finding Your Roots]]'', [[PBS]], March 25, 2012.</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Lewis |first1=John |title=Walking with the Wind: A Memoir of the Movement |publisher=[[Houghton Mifflin Harcourt]] |date=October 18, 1999 |isbn=9780156007085 |page=15}}</ref> His parents were [[Sharecropping|sharecroppers]]<ref name="ReportingCivilRights">''Reporting Civil Rights: American Journalism 1963–1973, Part Two ''[[Clayborne Carson|Carson, Clayborne]], [[David Garrow|Garrow, David]], Kovach, Polsgrove, Carol (Editorial Advisory Board), (Library of America: 2003) {{ISBN|978-1-931082-29-7}}, pp. 15–16, 48, 56, 84, 323, 374, 384, 392, 491–94, 503, 505, 513, 556, 726, 751, 846, 873.</ref> in rural [[Pike County, Alabama|Pike County]], Alabama.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Lewis |first1=John |title=Walking with the Wind: A Memoir of the Movement |publisher=Harcourt Brace |location=San Diego |page=xv}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | As a boy, Lewis aspired to be a [[preacher]];<ref name=Lemley>{{cite web |last1=Lemley |first1=John |last2=Johns |first2=Myke |title=Congressman John Lewis on March |date=August 28, 2013 |accessdate=July 20, 2020 |website=[[WABE|WABE-FM]] |location=[[Atlanta]] |url=https://www.wabe.org/congressman-john-lewis-march}} ([[NPR]] station)</ref> and at age five, he was preaching to his family's chickens on the farm.<ref name=Banks>{{cite news |last=Banks |first=Adelle M. |title=Died: John Lewis, Preaching Politician and Civil Rights Leader |type=obituary |date=July 18, 2020 |accessdate=July 20, 2020 |journal=[[Christianity Today]] |agency=[[Religion News Service]] |url=https://www.christianitytoday.com/news/2020/july/died-john-lewis-baptist-minister-civil-rights-leader.html}}</ref> As a young child, Lewis had little interaction with [[white people]]. In fact, by the time he was six, Lewis had seen only two white people in his life.<ref>{{cite book |title=Walking with the Wind: A Memoir of the Movement |url=https://archive.org/details/walkingwithwindm00lewi|url-access=registration |quote=john lewis The church he attended was attacked by the [Ku Klux Klan in 1904. |publisher=Simon & Schuster |location=New York |year=1998 |author=John Lewis |page=[https://archive.org/details/walkingwithwindm00lewi/page/n10 7] |accessdate=January 1, 2013 |isbn=978-0-15-600708-5}}</ref> As he grew older, he began taking trips into town with his family, where he experienced racism and segregation, such as at the public library in Troy.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Martin |first1=Brad |title=John Lewis Inspires Audience to March Forward While Remembering the Past |journal=ALA Cognotes |publisher=[[American Library Association]] |date=July 1, 2013 |volume=2013 |issue=8 |page=3 |url=http://exhibitors.ala.org/Cognotes_2013/Cognotes_July_1_2013.pdf |accessdate=December 31, 2019 |issn=0738-4319|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170320210115/http://exhibitors.ala.org/Cognotes_2013/Cognotes_July_1_2013.pdf|archive-date=March 20, 2017|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |title=John Lewis's March |journal=American Libraries |date=June 30, 2013 |url=https://americanlibrariesmagazine.org/blogs/the-scoop/john-lewiss-march/ |publisher=American Library Association |issn=0002-9769|access-date=December 31, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191231100653/https://americanlibrariesmagazine.org/blogs/the-scoop/john-lewiss-march/|archive-date=December 31, 2019|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite magazine |last1=Albanese |first1=Andrew |title=ALA 2013: The Day Congressman John Lewis Got his Library Card |magazine=[[Publishers Weekly]] |publisher=PWxyz, LLC |location=New York City |date=June 30, 2013 |url=https://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/digital/conferences/article/58040-ala-2013-the-day-congressman-john-lewis-got-his-library-card.html |accessdate=December 31, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191231093834/https://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/digital/conferences/article/58040-ala-2013-the-day-congressman-john-lewis-got-his-library-card.html|archive-date=December 31, 2019|url-status=live}}</ref> Lewis had relatives who lived in northern cities, and he learned from them that the North had integrated schools, buses, and businesses. When Lewis was 11, an uncle took him to [[Buffalo, New York|Buffalo]], New York, making him more acutely aware of Troy's segregation.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Lewis |first1=John |title=Walking with the Wind: A Memoir of the Movement |year=1999 |publisher=Harcourt Brace |location=San Diego, California |isbn=978-0-15-600708-5 |pages=36–40}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | In 1955, Lewis first heard [[Martin Luther King Jr.]] on the radio,<ref>{{cite book |last1=Lewis |first1=John |title=Walking with the Wind: A Memoir of the Movement |publisher=Harcourt Brace |location=San Diego |page=45}}</ref> and he closely followed King's [[Montgomery bus boycott]] later that year.<ref>Lewis, p. 48.</ref> At age 15, Lewis preached his first public sermon.<ref name=Banks/> Lewis met [[Rosa Parks]] when he was 17, and met King for the first time when he was 18.<ref name="NPR">{{cite episode |url=https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=5033971 |title=The Montgomery Bus Boycott, 50 Years Later |date=December 1, 2005 |network=[[NPR]] |series=[[News & Notes]] |access-date=April 6, 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180203005850/https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=5033971 |archive-date=February 3, 2018 |url-status=live}}</ref> After writing to King about being denied admission to [[Troy University]] in Alabama, Lewis was invited to a meeting. King, who referred to Lewis as "the boy from Troy," discussed suing the university for discrimination, but he warned Lewis that doing so could endanger his family in Troy. After discussing it with his parents, Lewis decided to proceed with his education at a small, [[historically black]] college in Tennessee.<ref>{{Cite magazine |last=Newkirk II |first=Vann R. |title=How Martin Luther King Jr. Recruited John Lewis |url=https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2018/02/john-lewis-martin-luther-king-jr/552581/ |magazine=The Atlantic |issn=1072-7825}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Lewis graduated from the [[American Baptist College|American Baptist Theological Seminary]] in [[Nashville, Tennessee]], and was ordained as a [[Baptists|Baptist]] minister.<ref name=Banks/><ref name=Lemley/> He then received a bachelor's degree in religion and philosophy from [[Fisk University]]. He was a member of [[Phi Beta Sigma]] fraternity.<ref>{{cite web |title=President Clinton Inducted into Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity |url=https://www.reuters.com/article/2009/07/11/idUS14578+11-Jul-2009+PRN20090711 |agency=Reuters |accessdate=January 1, 2013 |url-status=dead |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20130315092349/http://www.reuters.com/article/2009/07/11/idUS14578+11-Jul-2009+PRN20090711 |archivedate=March 15, 2013}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |date=July 19, 2020 |title="He fought until the end. That was my big brother" John Lewis’ family speaks for 1st time |work=[[WSB-TV|WSB News]] |url=https://www.wsbtv.com/news/local/he-fought-until-end-that-was-my-big-brother-john-lewis-family-speaks-1st-time/MYOXRZXBOVGATGRI72EC4ZEXS4/ |url-status=live |archive-url=https://archive.today/20200729171915/https://www.wsbtv.com/news/local/he-fought-until-end-that-was-my-big-brother-john-lewis-family-speaks-1st-time/MYOXRZXBOVGATGRI72EC4ZEXS4/ |archive-date=July 29, 2020}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Student activism and SNCC == | ||

| + | === Nashville Student Movement === | ||

| + | [[File:JFK meets with leaders of March on Washington 8-28-63.JPG|thumb|Civil rights leaders meet with President John F. Kennedy after the [[March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom]], 1963. Lewis is fourth from left.]] | ||

| + | As a student, Lewis was dedicated to the civil rights movement. He organized [[sit-ins]] at segregated lunch counters in Nashville and took part in many other civil rights activities as part of the [[Nashville Student Movement]]. The [[Nashville sit-ins|Nashville sit-in movement]] was responsible for the desegregation of lunch counters in downtown Nashville. Lewis was arrested and jailed many times in the nonviolent movement to desegregate the city's downtown area.<ref>{{cite web |title=Congressman John R. Lewis Biography and Interview |website=www.achievement.org |publisher=[[American Academy of Achievement]] |url=https://www.achievement.org/achiever/congressman-john-r-lewis/#interview |access-date=May 6, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190220101031/http://www.achievement.org/achiever/congressman-john-r-lewis/#interview |archive-date=February 20, 2019 |url-status=live}}</ref> He was also instrumental in organizing bus [[boycotts]] and other [[nonviolent]] protests to support voting rights and racial equality.{{citation needed|date=July 2020}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | During this time, Lewis expressed the need to engage in "good trouble, necessary trouble" to achieve change, and he held by the phrase and the sentiment throughout his life.<ref>{{cite news| url=https://www.latimes.com/politics/story/2020-07-17/rep-john-lewis-civil-rights-icon-dies| title=John Lewis, civil rights icon and longtime congressman, dies| last=Haberkorn| first=Jennifer| newspaper=[[Los Angeles Times]]| date=July 17, 2020}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | While a student, Lewis was invited to attend [[nonviolence]] workshops held at Clark Memorial United Methodist Church by the Rev. [[James Lawson (American activist)|James Lawson]] and Rev. [[Kelly Miller Smith]]. There, Lewis and other students became dedicated adherents to the discipline and philosophy of nonviolence, which he practiced for the rest of his life.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://snccdigital.org/people/john-lewis/ |title=John Lewis |access-date=January 4, 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180105070259/https://snccdigital.org/people/john-lewis/ |website=Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) Legacy Project |archive-date=January 5, 2018 |url-status=live}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Freedom Rides === | ||

| + | [[File:President Clinton at a Dinner Honoring Rep. John Lewis (2000).webm|thumb|Video of President Clinton delivering remarks at a dinner honoring Representative John Lewis]] | ||

| + | In 1961, Lewis became one of the 13 original [[Freedom Riders]].<ref name="ReportingCivilRights" /><ref>{{cite web |title=Freedom Rides |url=https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/encyclopedia/freedom-rides |website=King Encyclopedia |publisher=[[Stanford University]] |location=Stanford, California |accessdate=April 21, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200418222156/https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/encyclopedia/freedom-rides |archive-date=April 18, 2020 |url-status=live}}</ref> They were seven blacks and six whites determined to ride from [[Washington, D.C.]] to [[New Orleans]] in an integrated fashion. At that time, several southern states enforced laws prohibiting black and white riders from sitting next to each other on public transportation. The Freedom Ride, originated by the [[Fellowship of Reconciliation]] and revived by [[James Farmer]] and the [[Congress of Racial Equality]] (CORE), was initiated to pressure the federal government to enforce the Supreme Court decision in ''[[Boynton v. Virginia]]'' (1960) that declared segregated interstate bus travel to be unconstitutional. The Freedom Rides also exposed the government's passivity towards violence against law-abiding citizens.<ref name="CNN">{{cite web |url=http://articles.cnn.com/2001-05-10/us/access.lewis.freedom.rides_1_white-men-angry-mob-blacks?_s=PM:US |work=[[CNN]] |location=Atlanta |title=Civil Rights Timeline |date=January 31, 2006 |url-status=dead |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20120808153339/http://articles.cnn.com/2001-05-10/us/access.lewis.freedom.rides_1_white-men-angry-mob-blacks?_s=PM%3AUS |archivedate=August 8, 2012}}</ref> The federal government had trusted the notoriously [[racism|racist]] [[Alabama]] police to protect the Riders, but did nothing itself, except to have [[FBI]] agents take notes. The [[Kennedy Administration]] then called for a cooling-off period, with a moratorium on Freedom Rides.<ref name="FreedomAlbany" /> | ||

| + | |||

| + | In the South, Lewis and other nonviolent Freedom Riders were beaten by angry mobs and arrested. At age 21, Lewis was the first of the Freedom Riders to be assaulted while in [[Rock Hill, South Carolina]]. When he tried to enter a whites-only waiting room, two white men attacked him, injuring his face and kicking him in the ribs. Nevertheless, only two weeks later Lewis joined a ''Freedom Ride'' that was bound for [[Jackson, Mississippi]]. "We were determined not to let any act of violence keep us from our goal. We knew our lives could be threatened, but we had made up our minds not to turn back," Lewis said towards the end of his life about his perseverance following the act of violence.<ref name="SmithsonianMagazine">{{cite web |url=http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history-archaeology/The-Freedom-Riders.html?c=y&page=1 |title=The Freedom Riders, Then and Now |work=[[Smithsonian Magazine]] |accessdate=July 26, 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120924100804/http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history-archaeology/The-Freedom-Riders.html?c=y&page=1 |archive-date=September 24, 2012 |url-status=live}}</ref> Lewis was also imprisoned for 40 days in the [[Mississippi State Penitentiary]] in [[Sunflower County, Mississippi|Sunflower County]] after participating in a Freedom Riders activity.<ref>{{cite news |last=Minor |first=Bill |url=http://www.desototimes.com/articles/2010/04/02/opinion/editorials/doc4bb645d51cbc1161890108.txt |title=New law meant to eliminate existing 'donut hole' |newspaper=DeSoto Times-Tribune |location=Nesbit, Mississippi |date=April 2, 2010 |accessdate=February 25, 2019}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | In an interview with ''[[CNN]]'' during the 40th anniversary of the Freedom Rides, Lewis recounted the amount of violence he and the 12 other original Freedom Riders endured. In [[Birmingham, Alabama|Birmingham]], the Riders were beaten with baseball bats, chains, lead pipes, and stones. They were arrested by police who led them across the border into Tennessee and let them go. They reorganized and rode to [[Montgomery, Alabama|Montgomery]], where they were met with more violence,<ref>{{cite web |date=May 11, 2001 |title=40 years later, mission accomplished |url=https://www.cnn.com/2001/fyi/news/05/11/freedom.riders/ |url-status=live |access-date=July 18, 2020 |website=CNN |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20040813044815/http://www.cnn.com/2001/fyi/news/05/11/freedom.riders/ |archive-date=August 13, 2004}}</ref> and Lewis was hit in the head with a wooden crate. "It was very violent. I thought I was going to die. I was left lying at the [[Greyhound bus]] station in Montgomery unconscious," said Lewis, remembering the incident.<ref>{{cite news |url=https://edition.cnn.com/2001/US/05/10/access.lewis.freedom.rides/ |title=John Lewis: 'I thought I was going to die' |date=May 10, 2001 |work=[[CNN]] |access-date=March 8, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160401002256/http://edition.cnn.com/2001/US/05/10/access.lewis.freedom.rides/ |archive-date=April 1, 2016 |url-status=live}}</ref> When CORE gave up on the Freedom Ride because of the violence, Lewis and fellow activist [[Diane Nash]] arranged for the Nashville students to take it over and bring it to a successful conclusion.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Scott |first1=William R. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=vVvhAQAAQBAJ&pg=PA229 |title=Upon these Shores: Themes in the African-American Experience 1600 to the Present |last2=Shade |first2=William G. |date=October 31, 2013 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-135-27620-1 |language=en}}</ref><ref name="auto">{{cite book |last1=Lewis |first1=John |last2=Michael d'Orso |authorlink2=Mike D'Orso |title=Walking with the Wind: A Memoir of the Movement |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=mm58BgAAQBAJ |publisher=Harvest Books |year=1999 |edition=reprint |isbn=978-1-4767-9771-7 |pages=143–144}}</ref><ref name="auto" /> | ||

| + | |||

| + | In February 2009, 48 years after he was bloodied in a Greyhound station during a Freedom Ride, Lewis received a nationally televised apology from a white southerner and former [[Ku Klux Klan|Klansman]], Elwin Wilson.<ref name="abcnews.go.com">{{cite web |url=https://abcnews.go.com/print?id=6813984 |title=Once Race Riot Enemies, Now Friends |work=[[ABC News]] |date=February 6, 2009 |accessdate=August 22, 2010|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090211112207/http://abcnews.go.com/print?id=6813984|archive-date=February 11, 2009|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="ReferenceA">{{cite web |first1=Claire |last1=Shipman |first2=Cindy |last2=Smith |first3=Lee |last3=Ferran |url=https://abcnews.go.com/GMA/story?id=6813984&page=1 |title=Man Asks Entire Town for Forgiveness for Racism |work=ABC News |date=February 6, 2009 |accessdate=August 22, 2010|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090309165408/http://abcnews.go.com/GMA/story?id=6813984&page=1 |archive-date=March 9, 2009 |url-status=live}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Lewis wrote in 2015 that he knew [[Michael Schwerner]] and [[Andrew Goodman (activist)|Andrew Goodman]]. They, along with [[James Chaney]], were [[Murders of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner|abducted and murdered]] in June 1964 in [[Neshoba County, Mississippi]], by members of the [[Ku Klux Klan]].<ref>{{cite book| url=https://books.google.com/books?id=mm58BgAAQBAJ&pg=PA261| last1=Lewis |first1=John |last2=Michael d'Orso |title=Walking with the Wind: A Memoir of the Movement |publisher=Harvest Books |year=1999 |edition=reprint |isbn=978-1-4767-9771-7 |page=261}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | === SNCC Chairmanship === | ||

| + | [[File:Civil Rights March on Washington, D.C. (Leaders of the march) - NARA - 542056.jpg|thumb|left|Leaders of the March on Washington, 1963. Lewis is second from right.]] | ||

| + | In 1963, when [[Charles McDew]] stepped down as chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), Lewis, one of the founding members of SNCC, was elected to take over.<ref>{{cite news |last=Roberts |first=Sam |date=April 13, 2018 |title=Charles McDew, 79, Tactician for Student Civil Rights Group, Dies |language=en-US |work=The New York Times |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/13/obituaries/charles-mcdew-79-tactician-for-student-civil-rights-group-dies.html |access-date=July 18, 2020 |issn=0362-4331 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180617121359/https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/13/obituaries/charles-mcdew-79-tactician-for-student-civil-rights-group-dies.html |archive-date=June 17, 2018 |url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |last=Adler |first=Erin |date=April 18, 2018 |title=Charles McDew, civil rights activist and Metro State adviser, dies at 79 |url=https://www.startribune.com/charles-mcdew-civil-rights-activist-and-metro-state-adviser-dies-at-79/480174313/ |url-status=live |access-date=July 18, 2020 |newspaper=Star Tribune |location=[[Minneapolis]] |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180419074332/http://www.startribune.com/charles-mcdew-civil-rights-activist-and-metro-state-adviser-dies-at-79/480174313/ |archive-date=April 19, 2018}}</ref> Lewis's experience at that point was already widely respected. His courage and tenacious adherence to the philosophy of reconciliation and nonviolence made him emerge as a leader. By this time, he had been arrested 24 times in the nonviolent movement for equal justice.<ref>{{cite web |title=John Lewis, civil rights hero and 'conscience of Congress,' dies at 80 |url=https://www.rollcall.com/2020/07/18/john-lewis-civil-rights-hero-and-conscience-of-congress-has-died/ |newspaper=[[Roll Call]] |accessdate=July 18, 2020}}</ref> He served as chairman until 1966.<ref>{{cite news |date=July 18, 2020 |title=Civil rights icon and congressman John Lewis dies |language=en-GB |work=BBC News |url=https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-53454169 |access-date=July 18, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200718044207/https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-53454169 |archive-date=July 18, 2020 |url-status=live}}</ref> During his tenure, SNCC opened [[Freedom Schools]], launched the Mississippi [[Freedom Summer]],<ref>{{cite book |last=Hale |first=Jon N. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=GMZ1CwAAQBAJ&pg=PA72 |title=The Freedom Schools: Student Activists in the Mississippi Civil Rights Movement |date=June 7, 2016 |publisher=[[Columbia University Press]] |isbn=978-0-231-54182-4 |pages=72–75 |language=en}}</ref> and organized some of the voter registration efforts during the 1965 [[Selma to Montgomery marches|Selma voting rights campaign]].<ref>{{cite web |title=Selma voting rights campaign |url=https://snccdigital.org/events/selma-voting-rights-campaign/|access-date=July 18, 2020 |website=SNCC Digital Gateway |language=en |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200611081457/https://snccdigital.org/events/selma-voting-rights-campaign/ |archive-date=June 11, 2020 |url-status=live}}</ref> As the chairman of SNCC, Lewis had written a speech in reaction to the 1963 Civil Rights Bill. The planned speech denounced the bill because it did not protect African Americans against [[police brutality]] or provide African Americans with the right to vote; it described it as "too little and too late." But when copies of the speech were distributed on August 27, other chairs of the march insisted that it be revised. [[James Forman]] re-wrote Lewis's speech on a portable typewriter in a small anteroom behind Lincoln's statue during the program. SNCC's initial assertion "we cannot support, wholeheartedly the [Kennedy] civil rights bill” was replaced with “We support it with great reservations."<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/civil-rights-act/civil-rights-era.html |title=The Civil Rights Act of 1964: A Long Struggle for Freedom |accessdate=July 18, 2020 |website=Library of Congress |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200109202657/https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/civil-rights-act/civil-rights-era.html |archive-date=January 9, 2020 |url-status=live}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | In 1963, as chairman of SNCC, Lewis was named one of the "Big Six" leaders who were organizing the March on Washington, the occasion of Dr. Martin Luther King's celebrated "[[I Have a Dream]]" speech, along with [[Whitney Young]], [[A. Philip Randolph]], [[James Farmer]], and [[Roy Wilkins]]. Discussing the occasion, historian [[Howard Zinn]] wrote: "At the great Washington March of 1963, the chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), John Lewis, speaking to the same enormous crowd that heard King's "I Have a Dream" speech, was prepared to ask the right question: 'Which side is the federal government on?' That sentence was eliminated from his speech by the other organizers of the March to avoid offending the [[John F. Kennedy|Kennedy Administration]]. Lewis and his fellow SNCC workers had experienced the federal government's passivity in the face of Southern violence;<ref name="FreedomAlbany">{{cite web |url=http://www.zmag.org/zmag/articles/oldzinn.htm |title=My Name Is Freedom: Albany, Georgia |publisher=[[Beacon Press]] |location=Boston |website=You Can't Be Neutral on A Moving Train |url-status=dead |archiveurl=https://archive.today/19990219104007/http://www.zmag.org/zmag/articles/oldzinn.htm |archivedate=February 19, 1999}}</ref> Lewis, the youngest speaker that day,<ref>{{cite news |last=Bunn |first=Curtis |url=https://www.nbcnews.com/news/nbcblk/we-are-legacy-john-lewis-lives-generations-young-staffers-he-n1235038 |work=[[NBC News]] |title='We are the legacy': John Lewis lives on in the generations of young staffers he empowered |date=July 28, 2020 |accessdate=July 31, 2020 |archivedate=July 28, 2020 |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20200728123210/https://www.nbcnews.com/news/nbcblk/we-are-legacy-john-lewis-lives-generations-young-staffers-he-n1235038}}</ref> begrudgingly acquiesced<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2020/07/18/john-lewis-was-last-living-speaker-march-washington-civil-rights-leaders-asked-him-tone-it-down/ |title=At the 1963 March on Washington, civil rights leaders asked John Lewis to tone his speech down |newspaper=[[The Washington Post]] |last=Brockell |first=Gillian |date=July 18, 2020 |accessdate=July 31, 2020 |archivedate=July 18, 2020 |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20200718132118/https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2020/07/18/john-lewis-was-last-living-speaker-march-washington-civil-rights-leaders-asked-him-tone-it-down/}}</ref> and delivered the edited speech as the fourth speaker that day, ahead of the "I Have a Dream" speech by King<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.nola.com/opinions/article_87a3401f-b8eb-5854-a799-7ff8de67d412.html |title=March on Washington reflected optimism and outrage |last=Mann |first=Robert |date=August 24, 2013 |newspaper=[[The Times-Picayune/The New Orleans Advocate]] |accessdate=July 31, 2020 |archivedate=July 31, 2020 |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20200731204548/https://www.nola.com/opinions/article_87a3401f-b8eb-5854-a799-7ff8de67d412.html}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |first=William P. |last=Jones |url=https://archive.org/details/CSPAN2_20160219_070600_Book_Discussion_on_The_March_on_Washington/start/2305/end/2365?q=ethan+lewis |publisher=[[C-SPAN 2]] |date= February 19, 2016 |title=Book Discussion on The March on Washington |accessdate=July 31, 2020}}</ref> who served as the final speaker that day.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.core-online.org/History/washington_march.htm |title=March on Washington: The World Hears of Dr. King's 'Dream' |publisher=[[Congress of Racial Equality]] |year=2014 |accessdate=July 31, 2020 |archivedate=July 31, 2020 |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20200731205218/http://www.core-online.org/History/washington_march.htm}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

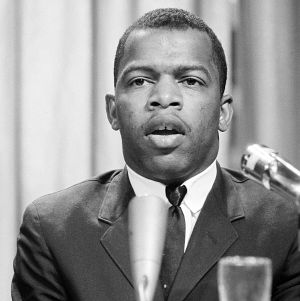

| + | [[File:John Lewis 1964-04-16 (cropped).jpg|thumb|right|Lewis in 1964]] | ||

| + | In 1964, Lewis coordinated SNCC's efforts for "[[Mississippi Freedom Summer]]," a campaign to register black voters across the South and expose college students from around the country to the perils of African-American life in the South. Lewis traveled the country, encouraging students to spend their summer break trying to help people vote in Mississippi, the most recalcitrant state in the union.<ref>{{cite news |last=Hannah-Jones |first=Nikole |date=August 19, 2014 |title=Long a Force for Progress, a Freedom Summer Legend Looks Back |url=https://www.propublica.org/article/long-a-force-for-progress-a-freedom-summer-legend-looks-back |work=[[ProPublica]] |accessdate=July 17, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200606105750/https://www.propublica.org/article/long-a-force-for-progress-a-freedom-summer-legend-looks-back |archive-date=June 6, 2020 |url-status=live}}</ref> Lewis became nationally known during his prominent role in the [[Selma to Montgomery marches]] when, on March 7, 1965 – a day that would become known as "[[Selma to Montgomery marches#"Bloody Sunday" events|Bloody Sunday]]" – Lewis and fellow activist [[Hosea Williams]] led over 600 marchers across the [[Edmund Pettus Bridge]] in [[Selma, Alabama]]. At the end of the bridge, they were met by [[Alabama Highway Patrol|Alabama State Troopers]] who ordered them to disperse. When the marchers stopped to pray, the police discharged [[tear gas]] and mounted troopers charged the demonstrators, beating them with nightsticks. Lewis's skull was fractured, but he escaped across the bridge to [[Brown Chapel A.M.E. Church (Selma, Alabama)|Brown Chapel]], a church in Selma that served as the movement's headquarters.<ref>{{cite news |last=Herndon |first=Astead W. |date=March 1, 2020 |title='Bloody Sunday' Commemoration Draws Democratic Candidates to Selma |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/01/us/politics/selma-bridge-march-2020-candidates.html |newspaper=[[The New York Times]] |accessdate=July 17, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200618214842/https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/01/us/politics/selma-bridge-march-2020-candidates.html |archive-date=June 18, 2020 |url-status=live}}</ref> Lewis bore scars on his head from the incident for the rest of his life.<ref>{{cite news |last1=Page |first1=Susan |title=50 years after Selma, John Lewis on unfinished business |url=https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2015/02/24/capital-download-john-lewis-selma-50th-anniversary/23935047/ |accessdate=April 20, 2020 |newspaper=[[USA Today]] |date=February 24, 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200301180115/https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2015/02/24/capital-download-john-lewis-selma-50th-anniversary/23935047/ |archive-date=March 1, 2020 |url-status=live}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Field Foundation, SRC, and VEP (1966–1977) == | ||

| + | In 1966, Lewis moved to [[New York City]] to take a job as the associate director of the [[Field Foundation]].<ref>Lewis, p. 392.</ref><ref name="cnn-fastfacts">{{cite news |title=John Lewis Fast Facts |url=https://www.cnn.com/2013/02/22/us/john-lewis-fast-facts/index.html |work=CNN |accessdate=April 22, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200416181223/https://www.cnn.com/2013/02/22/us/john-lewis-fast-facts/index.html |archive-date=April 16, 2020 |url-status=live}}</ref> He was there a little over a year before moving back to Atlanta to direct the [[Southern Regional Council]]'s Community Organization Project.<ref>Lewis, p. 398.</ref><ref name="cnn-fastfacts" /> During his time with the SRC, he completed his degree from Fisk University.<ref>Lewis, ''Walking with the Wind'', p. 400.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | In 1970, Lewis became the director of the [[Voter Education Project]] (VEP), a position he held until 1977.<ref name="wynn">{{cite web |last1=Wynn |first1=Linda T. |title=John Robert Lewis |url=https://tennesseeencyclopedia.net/entries/john-robert-lewis/ |website=Tennessee Encyclopedia |accessdate=April 20, 2020}}</ref> Though initially a project of the Southern Regional Council, the VEP became an independent organization in 1971.<ref name="ga-encyclopedia">{{cite web |title=Voter Education Project |url=https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/voter-education-project |website=Georgia Encyclopedia |accessdate=April 20, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200602125300/https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/voter-education-project |archive-date=June 2, 2020 |url-status=live}}</ref> Despite difficulties caused by the [[1973–1975 recession]],<ref name="ga-encyclopedia" /> the VEP added nearly four million minority voters to the rolls under Lewis's leadership.<ref name="encyclopedia-al">{{cite web |title=John Lewis |url=http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-1841 |website=Encyclopedia of Alabama |accessdate=April 20, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191221161052/http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-1841 |archive-date=December 21, 2019 |url-status=live}}</ref> During his tenure, the VEP expanded its mission, including running Voter Mobilization Tours.<ref name="ga-encyclopedia" /> | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Early work in government (1977-1986) == | ||

| + | In January 1977, incumbent Democratic U.S. Congressman [[Andrew Young]] of [[Georgia's 5th congressional district]] resigned to become the [[United States Ambassador to the United Nations|U.S. Ambassador to the U.N.]] under President [[Jimmy Carter]]. In the March 1977 open primary, [[Atlanta City Council]]man [[Wyche Fowler]] ranked first with 40% of the vote, failing to reach the 50% threshold to win outright. Lewis ranked second with 29% of the vote.<ref name="ourcampaigns.com">{{cite web |url=http://www.ourcampaigns.com/RaceDetail.html?RaceID=31297 |title=GA District 5 – Special Election Primary Race – Mar 15, 1977 |publisher=Our Campaigns |accessdate=July 26, 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131029200713/http://www.ourcampaigns.com/RaceDetail.html?RaceID=31297 |archive-date=October 29, 2013 |url-status=live}}</ref> In the April election, Fowler defeated Lewis 62%–38%.<ref name="ReferenceB">{{cite web |url=http://www.ourcampaigns.com/RaceDetail.html?RaceID=31302 |title=GA District 5 – Special Election Race – Apr 05, 1977 |publisher=Our Campaigns |accessdate=July 26, 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131029191811/http://www.ourcampaigns.com/RaceDetail.html?RaceID=31302 |archive-date=October 29, 2013 |url-status=live}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | After his unsuccessful bid, Lewis accepted a position with the Carter administration as associate director of [[ACTION (U.S. government agency)|ACTION]], responsible for running the [[Volunteers in Service to America|VISTA]] program, the Retired Senior Volunteer Program, and the [[Foster Grandparent Program]]. He held that job for two and a half years, resigning as the 1980 election approached.<ref>Lewis, ''Walking with the Wind'', pp. 446–451.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | In 1981, Lewis ran for an at-large seat on the [[Political structure of Atlanta|Atlanta City Council]]. He won with 69% of the vote,<ref>{{cite news |last1=Press |first1=Robert M. |title=Civil rights veteran John Lewis still marches to unmistakable drumbeat |url=https://www.csmonitor.com/1985/0228/alew.html |accessdate=April 18, 2020 |newspaper=[[The Christian Science Monitor]] |location=Boston |date=February 28, 1985 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151003103544/http://www.csmonitor.com/1985/0228/alew.html |archive-date=October 3, 2015 |url-status=live}}</ref> and served on the council until 1986.<ref>{{cite web |title=People – Lewis, John |url=https://georgiainfo.galileo.usg.edu/topics/people/article/civil-rights-activists/john-lewis |website=GeorgiaInfo |publisher=University System of Georgia |accessdate=April 18, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200531203243/https://georgiainfo.galileo.usg.edu/topics/people/article/civil-rights-activists/john-lewis |archive-date=May 31, 2020 |url-status=live}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | == U.S. House of Representatives == | ||

| + | === Elections === | ||

| + | ==== 1986 ==== | ||

| + | [[File:Reagan Contact Sheet C39369 (cropped).jpg|thumb|right|Lewis greets [[President of the United States|President]] [[Ronald Reagan]] and [[First Lady of the United States|First Lady]] [[Nancy Reagan]] in 1987.]] | ||

| + | After nine years as a member of the [[U.S. House of Representatives]], Fowler gave up the seat to make a successful run for the U.S. Senate. Lewis decided to run for the 5th district again. In the August Democratic primary, where a victory was considered [[tantamount to election]], State Representative [[Julian Bond]] ranked first with 47%, just three points shy of winning outright. Lewis finished in second place with 35%.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.ourcampaigns.com/RaceDetail.html?RaceID=388755 |title=GA District 5 – D Primary Race – Aug 12, 1986 |publisher=Our Campaigns |accessdate=July 26, 2012|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131029191616/http://www.ourcampaigns.com/RaceDetail.html?RaceID=388755|archive-date=October 29, 2013|url-status=live}}</ref> In the run-off, Lewis pulled an upset against Bond, defeating him 52% to 48%.<ref name="ReferenceC">{{cite web |url=http://www.ourcampaigns.com/RaceDetail.html?RaceID=388754 |title=GA District 5 – D Runoff Race – Sep 02, 1986 |publisher=Our Campaigns |accessdate=July 26, 2012|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131029192722/http://www.ourcampaigns.com/RaceDetail.html?RaceID=388754|archive-date=October 29, 2013|url-status=live}}</ref> The race was said to have "badly strained relations in Atlanta's black community" as many Black leaders had supported Bond over Lewis.<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://bittersoutherner.com/2020/the-way-of-john-lewis-cynthia-tucker-black-lives-matter |title=The Way of John Lewis |website=THE BITTER SOUTHERNER}}</ref> Lewis was "endorsed by the Atlanta newspapers and a favorite of the white liberal establishment."<ref name=":0" /> His victory was due to strong results among white voters (a minority in the district).<ref name=":0" /> During the campaign, he ran advertisements accusing Bond of corruption, implying that Bond used [[cocaine]], and suggesting that Bond had lied about his civil rights activism.<ref name=":0">{{cite news |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1986/09/03/us/ex-colleague-upsets-julian-bond-in-atlanta-congressional-runoff.html |title=Ex-Colleague Upsets Julian Bond in Atlanta Congressional Runoff |first=Dudley |last=Clendinen |newspaper=[[The New York Times]] |date=September 3, 1986 |accessdate=August 16, 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150820063819/http://www.nytimes.com/1986/09/03/us/ex-colleague-upsets-julian-bond-in-atlanta-congressional-runoff.html |archive-date=August 20, 2015|url-status=live}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | In the November general election, Lewis defeated Republican Portia Scott 75% to 25%.<ref name="ourcampaigns1">{{cite web |url=http://www.ourcampaigns.com/RaceDetail.html?RaceID=38194 |title=GA District 5 Race – Nov 04, 1986 |publisher=Our Campaigns |accessdate=July 26, 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131029192925/http://www.ourcampaigns.com/RaceDetail.html?RaceID=38194 |archive-date=October 29, 2013 |url-status=live}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==== 1988–2018 ==== | ||

| + | Lewis was reelected 16 times, dropping below 70 percent of the vote in the general election only once in 1994, when he defeated Republican Dale Dixon by a 38-point margin, 69%–31%.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.ourcampaigns.com/RaceDetail.html?RaceID=28773 |title=GA District 5 Race – Nov 08, 1994 |publisher=Our Campaigns |accessdate=July 26, 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131029194206/http://www.ourcampaigns.com/RaceDetail.html?RaceID=28773 |archive-date=October 29, 2013 |url-status=live}}</ref> He ran unopposed in 1996,<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.aclu.org/congressman-john-lewis |title=Congressman John Lewis |website=American Civil Liberties Union}}</ref> 2004,<ref name="2004Election">{{cite web |url=https://history.house.gov/Institution/Election-Statistics/2004election/ |page=16 |title=Statistics of the Congressional Election, 2004 |website=[[United States House of Representatives]] |accessdate=July 18, 2020}}</ref> 2006,<ref name="2006Election">{{cite web |url=https://history.house.gov/Institution/Election-Statistics/2006election/ |page=11 |title=Statistics of the Congressional Election, 2006 |website=[[United States House of Representatives]] |accessdate=July 18, 2020}}</ref> and 2008,<ref name="2008Election">{{cite web |url=https://history.house.gov/Institution/Election-Statistics/2008election/ |p=16 |title=Statistics of the Congressional Election, 2008 |website=United States House of Representatives |accessdate=July 18, 2020}}</ref> and again in 2014 and 2018.<ref name="2014Election">{{cite web |url=https://history.house.gov/Institution/Election-Statistics/2014election/ |p=12 |title=Statistics of the Congressional Election, 2014 |work=United States House of Representatives |accessdate=July 18, 2020}}</ref><ref name="2018Election">{{cite web |url=https://history.house.gov/Institution/Election-Statistics/2018election/ |p=12 |title=Statistics of the Congressional Election, 2018 |website=United States House of Representatives |accessdate=July 18, 2020}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | He was challenged in the Democratic primary just twice: in 1992 and 2008. In 1992, he defeated State Representative [[Mable Thomas]] 76%–24%.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.ourcampaigns.com/RaceDetail.html?RaceID=513779 |title=GA District 5 – D Primary Race – Jul 21, 1992 |publisher=Our Campaigns |accessdate=July 26, 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131029193651/http://www.ourcampaigns.com/RaceDetail.html?RaceID=513779 |archive-date=October 29, 2013 |url-status=live}}</ref> In 2008, Thomas decided to challenge Lewis again, as well and Markel Hutchins also contested the race. Lewis defeated Hutchins and Thomas 69%–16%–15%.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.ourcampaigns.com/RaceDetail.html?RaceID=384597 |title=GA District 5 – D Primary Race – Jul 15, 2008 |publisher=Our Campaigns |accessdate=July 26, 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150924164420/http://www.ourcampaigns.com/RaceDetail.html?RaceID=384597 |archive-date=September 24, 2015 |url-status=live}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Tenure === | ||

| + | ==== Overview ==== | ||

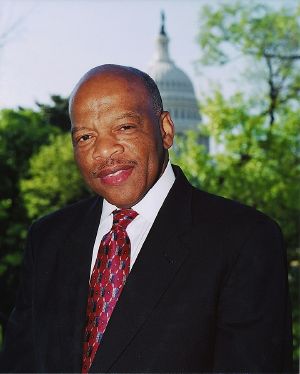

| + | [[File:John Lewis official biopic.jpg|thumb|An official portrait of Lewis]] | ||

| + | Lewis represented [[Georgia's 5th congressional district]], one of the most consistently Democratic districts in the nation. Since its formalization in 1845, the district has been represented by a Democrat for most of its history. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Lewis was one of the most liberal members of the House and one of the most liberal congressmen to have represented a district in the Deep South. He was categorized as a "Hard-Core Liberal" by [[On the Issues]].<ref name="Lewis 2000">{{cite web |title=Issues 2000 Lewis |url=http://www.issues2000.org/GA/John_Lewis.htm |publisher=Issues2000|access-date=June 14, 2012|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120513215725/http://issues2000.org/GA/John_Lewis.htm|archive-date=May 13, 2012|url-status=live}}</ref> ''[[The Washington Post]]'' described Lewis in 1998 as "a fiercely partisan Democrat but ... also fiercely independent."<ref name="Fighter">"Nonviolent Fighter; John Lewis Retraces the Route That Led to the Future": Carlson, Peter. ''The Washington Post'' [Washington, D.C] June 9, 1998: 01.</ref> Lewis characterized himself as a strong and adamant [[Modern liberalism in the United States|liberal]].<ref name="Fighter" /> ''[[The Atlanta Journal-Constitution]]'' said Lewis was the "only former major civil rights leader who extended his fight for human rights and racial reconciliation to the halls of Congress."<ref name="Conscience">{{cite news |title=John Lewis: 'Conscience' carries clout: Civil rights icon's moral authority enhanced |last=Kemper |first=Bob |newspaper=[[The Atlanta Journal-Constitution]] |date=May 21, 2006}}</ref> ''[[The Atlanta Journal-Constitution]]'' also said that to "those who know him, from U.S. senators to 20-something congressional aides," he is called the "conscience of Congress."<ref name="Conscience" /> Lewis cited Florida Senator and later Representative [[Claude Pepper]], a staunch liberal, as being the colleague whom he most admired.<ref name="EmoryWheel_Smith_20080421">{{cite web |url=http://emorywheel.com/detail.php?n=25537 |title=The Tuesday Ten: An Interview with Rep. John Lewis |first=Asher |last=Smith |work=[[The Emory Wheel]] |date=April 21, 2008 |url-status=dead |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20090124225545/http://emorywheel.com/detail.php?n=25537 |archivedate=January 24, 2009}}</ref> Lewis also spoke out in support of [[gay rights]] and [[national health insurance]].<ref name="Fighter" /> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Lewis opposed the 1991 [[Gulf War]],<ref>{{cite news |title=Mideast Trip Strengthens Georgia Lawmakers' Resolve |first=Mike |last=Christensen |newspaper=The Atlanta Journal-Constitution |date=January 11, 1991 |page=A7}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |title=Tour labors in opposition to NAFTA |first=Colin |last=Campbell |newspaper=Atlanta Journal-Constitution |date=February 19, 1998 |page=F02}}</ref> and the 2000 U.S. trade agreement with China that passed the House.<ref>{{cite web |title=The China trade vote: A Clinton triumph; House, in 237–197 vote, approves normal trade rights for China |first1=Eric |last1=Schmitt |first2=Joseph |last2=Kahn |newspaper=The New York Times |date=May 25, 2000 |url=https://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9F05E7D9153DF936A15756C0A9669C8B63&pagewanted=all |accessdate=February 27, 2011}}</ref> He opposed the [[Clinton administration]] on [[NAFTA]] and [[Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act|welfare reform]].<ref name="Fighter" /> After welfare reform passed, Lewis was described as outraged; he said, "Where is the sense of decency? What does it profit a great nation to conquer the world, only to lose its soul?"<ref>{{cite journal |title=Social programs: world report. The wreck of the gravy train |journal=Canada and the World Backgrounder |publisher=Taylor Publishing Consultants |location=Waterloo, Ontario |volume=62 |issue=2 |date=October 1996 |pages=3–34}}</ref> In 1994, when [[Foreign policy of the Bill Clinton administration#Haiti|Clinton was considering invading Haiti]], Lewis, in contrast to the Congressional Black Caucus as a whole, opposed armed intervention.<ref>{{cite news |title=President faces strong opposition in Congress |first=Sharon |last=Schmickle |newspaper=Star Tribune |location=Minneapolis |date=September 16, 1994 |page=1}}</ref> When Clinton did send troops to Haiti, Lewis called for [[Support our troops|supporting the troops]] and called the intervention a "mission of peace."<ref>"Shared power, foreign policy, and Haiti, 1994. Public memories of war and race." Goodnight, G. Thomas; Olson, Kathryn M.; ''Rhetoric & Public Affairs'' 9. 4 (Winter 2006): 601–634.</ref> In 1998, when Clinton was considering a military strike against Iraq, Lewis said he would back the president if American forces were ordered into action.<ref>{{cite news |title=Georgia delegation divided on strategy; Some back force, others doubt military action is a real solution |first=Mark |last=Sherman |newspaper=The Atlanta Constitution |date=February 12, 1998 |page=A14}}</ref> In 2001, three days after the [[September 11 attacks]], Lewis voted to give President [[George W. Bush]] authority to use force against the perpetrators of [[9/11]] in a vote that was 420–1; Lewis called it probably one of his toughest votes.<ref name="Tough">{{cite news |title=Congress using religious compass in decisions |first=Melanie |last=Eversley |newspaper=The Atlanta Journal-Constitution |date=October 7, 2001 |page=7}}</ref> In 2002, he sponsored the [[Peace Tax Fund bill]], a [[conscientious objection to military taxation]] initiative that had been reintroduced yearly since 1972.<ref>{{cite web |title=War Resisters: 'We Won't Go' To 'We Won't Pay' |first=Felicia R. |last=Lee |newspaper=The New York Times |date=August 3, 2002 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2002/08/03/arts/war-resisters-we-won-t-go-to-we-won-t-pay.html |accessdate=March 1, 2011|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131113085527/http://www.nytimes.com/2002/08/03/arts/war-resisters-we-won-t-go-to-we-won-t-pay.html|archive-date=November 13, 2013|url-status=live}}</ref> Lewis was a "fierce partisan critic of President Bush,” and an early opponent of the Iraq war.<ref name="Conscience" /><ref>{{cite web |last=Davis |first=Charles |title=Rep. John Lewis, civil rights icon, was a powerful voice against war with Iraq |url=https://www.businessinsider.com/john-lewis-was-a-lonely-voice-against-war-with-iraq-2020-7|access-date=July 18, 2020 |website=[[Business Insider]]}}</ref> The [[Associated Press]] said he was "the first major House figure to suggest [[Movement to impeach George W. Bush|impeaching George W. Bush,]]" arguing that the president "deliberately, systematically violated the law" in authorizing the [[National Security Agency]] to [[N.S.A. surveillance without warrants controversy|conduct wiretaps without a warrant]]. Lewis said, "He is not king, he is president."<ref name="VandenHeuvel">{{cite web |url=http://www.thenation.com/blogs/edcut?pid=45006 |title=The I-Word is Gaining Ground |first=Katrina |last=Vanden Heuvel |date=January 2, 2006 |work=[[The Nation]]|access-date=February 29, 2008|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071120065321/http://www.thenation.com/blogs/edcut?pid=45006|archive-date=November 20, 2007|url-status=live}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Lewis drew on his historical involvement in the [[Civil Rights Movement]] as part of his politics. He made an annual pilgrimage to Alabama to retrace the route he marched in 1965 from Selma to Montgomery – a route Lewis worked to make part of the [[National Historic Trail|Historic National Trails]] program. That trip became "one of the hottest tickets in Washington among lawmakers, Republican and Democrat, eager to associate themselves with Lewis and the movement. 'We don't deliberately set out to win votes, but it's very helpful," Lewis said of the trip'."<ref name="Conscience" /> In recent years, however, [[Faith and Politics Institute]] drew criticism for selling seats on the trip to lobbyists for at least $25,000 each. According to the Center for Public Integrity, even Lewis said that he would feel "much better" if the institute's funding came from churches and foundations instead of corporations.<ref name="publicintegrity.org">Guevara, Marina Walker (June 8, 2006). [https://www.publicintegrity.org/2006/06/08/5606/lobbyists-tag-along-civil-rights-tour "Lobbyists tag along on civil rights tour"]. {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160829024959/https://www.publicintegrity.org/2006/06/08/5606/lobbyists-tag-along-civil-rights-tour |date=August 29, 2016}}, The Center for Public Integrity.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | On June 3, 2011, the House passed a resolution 268–145, calling for a withdrawal of the United States military from the [[2011 military intervention in Libya|air and naval operations]] in and around [[Libya]].<ref>{{cite news |title=House Rebukes Obama for Continuing Libyan Mission Without Its Consent |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2011/06/04/world/africa/04policy.html?_r=1 |newspaper=The New York Times |date=June 4, 2011|access-date=December 31, 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181230234050/https://www.nytimes.com/2011/06/04/world/africa/04policy.html?_r=1|archive-date=December 30, 2018|url-status=live}}</ref> Lewis voted against the resolution.<ref>{{cite web |title=H.Res.292 – Declaring that the President shall not deploy, establish, or maintain the presence of units and members of the United States Armed Forces on the ground in Libya, and for other purposes. |url=https://www.congress.gov/bill/112th-congress/house-resolution/292/actions |website=Library of Congress |year=2011 |access-date=December 31, 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181231194241/https://www.congress.gov/bill/112th-congress/house-resolution/292/actions |archive-date=December 31, 2018 |url-status=live}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Lewis "strongly disagreed" with the movement for [[Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions]] (BDS) against [[Israel]] and co-sponsored resolution condemning the pro-Palestinian BDS, but he supported [[Ilhan Omar]]'s and [[Rashida Tlaib]]'s House resolution opposing [[Israel Anti-Boycott Act|U.S. anti-boycott legislation]] banning the boycott of Israel. He explained his support as "a simple demonstration of my ongoing commitment to the ability of every American to exercise the fundamental [[First Amendment]] right to protest through nonviolent actions."<ref>{{cite news |title=Rep. John Lewis backs the right to boycott Israel — even though he opposes BDS |url=https://www.timesofisrael.com/john-lewis-backs-the-right-to-boycott-israel-even-though-he-opposes-bds/ |work=The Times of Israel |date=July 27, 2019}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==== Protests ==== | ||

| + | In January 2001, Lewis [[boycott]]ed the [[First inauguration of George W. Bush|inauguration of George W. Bush]] by staying in his [[Atlanta]] district. He did not attend the swearing-in because he did not believe Bush was the true elected president.<ref>{{cite news |last=Merida |first=Kevin |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A24413-2001Jan20.html |title=So Close, So Far: A Texas Democrat's Day Without Sunshine |newspaper=The Washington Post |date=January 21, 2001 |accessdate=January 17, 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170117032230/http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A24413-2001Jan20.html |archive-date=January 17, 2017 |url-status=live}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | In March 2003, Lewis spoke to a crowd of 30,000 in Oregon during an anti-war protest before the start of the [[Iraq War]].<ref>{{cite news| url=https://www.nytimes.com/2003/03/16/us/threats-and-responses-dissent-tens-of-thousands-march-against-iraq-war.html| title=Tens of Thousands March Against Iraq War| archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170118042718/http://www.nytimes.com/2003/03/16/us/threats-and-responses-dissent-tens-of-thousands-march-against-iraq-war.html| archive-date=January 18, 2017| last=Lichtblau| first=Eric| newspaper=The New York Times| date=March 16, 2003| page=1}}</ref> In 2006<ref>Kemper, Bob (May 17, 2006). "Lewis, 6 other lawmakers arrested in embassy protest": ''The Atlanta Journal-Constitution'': p. 3.</ref> and 2009 he was arrested for protesting against the [[genocide in Darfur]] outside the [[Sudan]]ese embassy.<ref>{{cite web |title=U.S. lawmakers arrested in Darfur protests at Sudan embassy |work=CNN |url=https://politicalticker.blogs.cnn.com/2009/04/27/us-lawmakers-arrested-in-darfur-protest-at-sudan-embassy/ |accessdate=April 27, 2009 |date=April 27, 2009 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090430065243/http://politicalticker.blogs.cnn.com/2009/04/27/us-lawmakers-arrested-in-darfur-protest-at-sudan-embassy/ |archive-date=April 30, 2009 |url-status=live}}</ref> He was one of eight U.S. Representatives, from six states, arrested while holding a sit-in near the west side of the [[U.S. Capitol]] building, to advocate for immigration reform.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://nbcpolitics.nbcnews.com/_news/2013/10/08/20874725-democratic-lawmakers-arrested-during-immigration-protest?lite |title=Democratic lawmakers arrested during immigration protest |work=NBC News |date=October 8, 2013 |accessdate=November 9, 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131122081738/http://nbcpolitics.nbcnews.com/_news/2013/10/08/20874725-democratic-lawmakers-arrested-during-immigration-protest?lite |archive-date=November 22, 2013 |url-status=live}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==== 2008 presidential election ==== | ||

| + | [[File:John Lewis DNC 2008 (cropped2).jpg|thumb|Lewis speaks during the final day of the [[2008 Democratic National Convention]] in [[Denver]], Colorado|alt=]] | ||

| + | At first, Lewis supported [[Hillary Clinton]], endorsing her presidential campaign on October 12, 2007.<ref name="CNNticker_20071012">{{cite news |accessdate=May 6, 2010 |url=http://politicalticker.blogs.cnn.com/2007/10/12/rep-lewis-endorses-clinton/ |date=October 12, 2007 |title=Rep. Lewis endorses Clinton |work=CNN Political Ticker |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090406175833/http://politicalticker.blogs.cnn.com/2007/10/12/rep-lewis-endorses-clinton/ |archive-date=April 6, 2009 |url-status=live}}</ref> On February 14, 2008, however, he announced he was considering withdrawing his support from Clinton and might instead cast his [[superdelegate]] vote for [[Barack Obama]]: "Something is happening in America and people are prepared and ready to make that great leap."<ref name="NYT_Zeleny">{{cite news |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2008/02/15/us/politics/15clinton.html |title=Black Leader, a Clinton Ally, Tilts to Obama |last1=Zeleny |first1=Jeff |author2=Patrick Healy |date=February 15, 2008 |quote=Representative John Lewis said he planned to cast his vote as a superdelegate for Barack Obama in hopes of preventing a fight at the Democratic convention. |newspaper=The New York Times |access-date=February 17, 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170311195613/http://www.nytimes.com/2008/02/15/us/politics/15clinton.html |archive-date=March 11, 2017 |url-status=live}}</ref> [[Ben Smith (journalist)|Ben Smith]] of ''Politico'' said that "it would be a seminal moment in the race if John Lewis were to switch sides."<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.politico.com/blogs/bensmith/0208/Awaiting_Lewis.html |title=Awaiting Lewis |first=Ben |last=Smith |date=February 15, 2008 |work=Politico |accessdate=August 1, 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131029195727/http://www.politico.com/blogs/bensmith/0208/Awaiting_Lewis.html |archive-date=October 29, 2013 |url-status=live}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | On February 27, 2008, Lewis formally changed his support and endorsed Obama.<ref name="LAT_AP">{{cite web |accessdate=February 28, 2008 |url=https://www.latimes.com/news/politics/la-na-endorse28feb28,1,3290763.story |title=Civil rights leader John Lewis switches to Obama |quote=The Georgia congressman, who had previously endorsed Clinton, says he wants 'to be on the side of the people.' |date=February 28, 2008 |agency=Associated Press |newspaper=Los Angeles Times |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20080304010308/http://www.latimes.com/news/politics/la-na-endorse28feb28%2C1%2C3290763.story |archivedate=March 4, 2008 |url-status=dead}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |accessdate=May 6, 2010 |url=http://politicalticker.blogs.cnn.com/2008/02/27/lewis-switches-from-clinton-to-obama/ |date=February 27, 2008 |title=Lewis switches from Clinton to Obama |work=CNN Political Ticker |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100311075152/http://politicalticker.blogs.cnn.com/2008/02/27/lewis-switches-from-clinton-to-obama/|archive-date=March 11, 2010|url-status=live}}</ref> After Obama clinched the Democratic nomination for president, Lewis said "If someone had told me this would be happening now, I would have told them they were crazy, out of their mind, they didn't know what they were talking about ... I just wish the others were around to see this day. ... To the people who were beaten, put in jail, were asked questions they could never answer to register to vote, it's amazing."<ref name="Politico_Hearn_20080604">{{cite web |url=http://www.politico.com/news/stories/0608/10858.html |title=Black lawmakers emotional about Obama's success |date=June 4, 2008 |last=Hearn |first=Josephine |work=Politico |accessdate=June 5, 2008 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080608073714/http://www.politico.com/news/stories/0608/10858.html |archive-date=June 8, 2008 |url-status=live}}</ref> Despite switching his support to Obama, Lewis's support of Clinton for several months led to criticism from his constituents. One of his challengers in the House [[primary election]] set up campaign headquarters inside the building that served as Obama's Georgia office.<ref name="NYT_Hernandez_20080701">{{cite news |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/01/us/politics/01dems.html?ref=politics |author=Hernandez, Raymond |date=July 1, 2008 |title=A New Campaign Charge: You Supported Clinton |newspaper=New York Times |access-date=February 17, 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170104091011/http://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/01/us/politics/01dems.html?ref=politics |archive-date=January 4, 2017 |url-status=live}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | In October 2008, Lewis issued a statement criticizing the campaign of [[John McCain]] and [[Sarah Palin]] and accusing them of "sowing the seeds of hatred and division" in a way that brought to mind the late Gov. [[George Wallace]] and "another destructive period" in American political history. McCain said he was "saddened" by the criticism from "a man I've always admired," and called on Obama to repudiate Lewis's statement. Obama responded to the statement, saying that he "does not believe that John McCain or his policy criticism is in any way comparable to George Wallace or his segregationist policies."<ref name="Obama Rebukes">{{cite web |title=Congressman Rebukes McCain for Recent Rallies |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2008/10/12/us/politics/12lewis.html?_r=1&ref=johnlewis |newspaper=The New York Times |first=Elisabeth |last=Bumiller |date=October 12, 2008|access-date=February 17, 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180208123650/http://www.nytimes.com/2008/10/12/us/politics/12lewis.html?_r=1&ref=johnlewis|archive-date=February 8, 2018|url-status=live}}</ref> Lewis later issued a follow-up statement clarifying that he had not compared McCain and Palin to Wallace himself, but rather that his earlier statement was a "reminder to all Americans that toxic language can lead to destructive behavior."<ref name="AJC">{{cite news |url=http://www.ajc.com/metro/content/shared-blogs/ajc/politicalinsider/entries/2008/10/11/ |title=John McCain equal to George Wallace? Barack Obama says 'no,' and John Lewis says he's been misunderstood |date=October 11, 2008 |access-date=May 11, 2009 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110604113319/http://www.ajc.com/metro/content/shared-blogs/ajc/politicalinsider/entries/2008/10/11/ |newspaper=The Atlanta Journal-Constitution |archive-date=June 4, 2011 |url-status=live}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | On an African American being elected president, he said:{{quote|If you ask me whether the election ... is the fulfillment of Dr. King's dream, I say, "No, it's just a down payment." There's still too many people 50 years later, there's still too many people that are being left out and left behind.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Carter |first1=Lauren |title=Rep. John Lewis reflects on the 50th Anniversary of the March on Washington |url=http://thegrio.com/2013/08/21/rep-john-lewis-reflects-on-the-50th-anniversary-of-the-march-on-washington/ |website=The Grio |accessdate=24 September 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160924110239/http://thegrio.com/2013/08/21/rep-john-lewis-reflects-on-the-50th-anniversary-of-the-march-on-washington/ |archive-date=September 24, 2016 |url-status=live}}</ref>}}After Obama's swearing-in ceremony as president, Lewis asked Obama to sign a commemorative photograph of the event. Obama signed it, "Because of you, John. Barack Obama."<ref name=Remnick>{{cite magazine |last=Remnick |first=David |title=The President's Hero |url=https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2009/02/02/the-presidents-hero|access-date=July 19, 2020 |magazine=[[The New Yorker]] |language=en-us |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131029202722/http://www.newyorker.com/talk/comment/2009/02/02/090202taco_talk_remnick |archive-date=October 29, 2013 |url-status=live}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==== 2016 firearm safety legislation sit-in ==== | ||

| + | [[File:US House Democrats assume floor and begin 22 June 2016 sit in.png|thumb|House Democrats, led by Lewis, take the floor to begin a sit-in demanding [[gun control|gun safety legislation]] on June 22, 2016]] | ||

| + | [[2016 United States House of Representatives sit-in|On June 22, 2016, House Democrats, led by Lewis]] and Massachusetts Representative [[Katherine Clark]], began a sit-in demanding House Speaker [[Paul Ryan]] allow a vote on [[gun control|gun-safety legislation]] in the aftermath of the [[Orlando nightclub shooting]]. Speaker ''[[pro tempore]]'' [[Daniel Webster (Florida politician)|Daniel Webster]] ordered the House into recess, but Democrats refused to leave the chamber for nearly 26 hours.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Bade |first1=Rachael |title=Democrats stage sit-in on House floor to force gun vote |url=http://www.politico.com/story/2016/06/democrats-stage-sit-in-on-house-floor-to-force-gun-vote-224656 |website=Politico |accessdate=June 23, 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160622215704/http://www.politico.com/story/2016/06/democrats-stage-sit-in-on-house-floor-to-force-gun-vote-224656 |archive-date=June 22, 2016 |url-status=live}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==== National African American Museum ==== | ||

| + | In 1988, the year after he was sworn into Congress, Lewis introduced a bill to create a national African American museum in Washington. The bill failed, and for 15 years he continued to introduce it with each new Congress. Each time it was blocked in the Senate, most often by conservative Southern Senator [[Jesse Helms]]. In 2003, Helms retired. The bill won bipartisan support, and President George W. Bush signed the bill to establish the museum, with the [[Smithsonian]]'s Board of Regents to establish the location. The [[National Museum of African American History and Culture]], located adjacent to the [[Washington Memorial]], held its opening ceremony on September 25, 2016.<ref name="The Washington Post">{{cite news |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/entertainment/museums/for-rep-john-lewis-african-american-museum-was-a-recurring-dream/2016/06/28/fc05c81c-34b6-11e6-95c0-2a6873031302_story.html |title=For Rep. John Lewis, African American Museum was a recurring dream |last=McGione |first=Peggy |date=June 28, 2016 |access-date=January 16, 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170216134746/https://www.washingtonpost.com/entertainment/museums/for-rep-john-lewis-african-american-museum-was-a-recurring-dream/2016/06/28/fc05c81c-34b6-11e6-95c0-2a6873031302_story.html |archive-date=February 16, 2017 |url-status=live |newspaper=The Washington Post}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==== 2016 presidential election ==== | ||

| + | [[File:Atlanta Womens March John Lewis.jpg|thumb|John Lewis at the [[2017 Women's March]] in Atlanta]] | ||

| + | Lewis supported [[Hillary Clinton]] in the 2016 Democratic presidential primaries against [[Bernie Sanders]]. Regarding Sanders's role in the civil rights movement, Lewis remarked "To be very frank, I never saw him, I never met him. I chaired the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee for three years, from 1963 to 1966. I was involved in sit-ins, in the Freedom Rides, the March on Washington, the March from Selma to Montgomery... but I met Hillary Clinton". Former Congressman and Hawaii Governor [[Neil Abercrombie]] wrote a letter to Lewis expressing his disappointment with Lewis's comments on Sanders. Lewis later clarified his statement, saying "During the late 1950s and 1960s when I was more engaged, [Sanders] was not there. I did not see him around. I have never seen him in the South. But if he was there, if he was involved someplace, I was not aware of it."<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.burlingtonfreepress.com/story/news/2016/02/13/rep-lewis-softens-dismissal-sanders/80344896/ |title=Rep. Lewis softens dismissal of Sanders |date=February 13, 2016 |first=Meg |last=Kinnard |agency=Associated Press |work=[[Burlington Free Press]] |accessdate=February 25, 2019}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.politico.com/story/2016/02/after-2008-flip-flop-john-lewis-barnstorms-hard-for-clinton-campaign-219307 |title=Hillary Clinton's secret weapon: John Lewis |first=Patrick |last=Temple-West |date=February 15, 2016 |website=Politico |accessdate=February 25, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190503064320/https://www.politico.com/story/2016/02/after-2008-flip-flop-john-lewis-barnstorms-hard-for-clinton-campaign-219307 |archive-date=May 3, 2019 |url-status=live}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | In a January 2016 interview, Lewis compared [[Donald Trump]], then the [[Republican Party (United States)|Republican]] front-runner, to former Governor [[George Wallace]]: "I've been around a while and Trump reminds me so much of a lot of the things that George Wallace said and did. I think [[demagogues]] are pretty dangerous, really... We shouldn't divide people, we shouldn't separate people."<ref name="LAT_Panzar">{{cite web |url=https://www.latimes.com/local/lanow/la-me-ln-rep-john-lewis-trump-others-la-visit-20160123-story.html |title=Rep. John Lewis speaks out against Trump's divisive rhetoric during L.A. visit |last=Panzar |first=Javier |date=January 23, 2016 |quote=I've been around a while and Trump reminds me so much of a lot of the things that George Wallace said and did. I think demagogues are pretty dangerous, really [and] we shouldn't divide people, we shouldn't separate people. |newspaper=The Los Angeles Times |access-date=February 18, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190611125950/https://www.latimes.com/local/lanow/la-me-ln-rep-john-lewis-trump-others-la-visit-20160123-story.html |archive-date=June 11, 2019 |url-status=live}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | On January 13, 2017, during an interview with [[NBC]]'s [[Chuck Todd]] for ''[[Meet the Press]]'', Lewis stated: "I don't see the president-elect as a legitimate president."<ref>{{cite web |last1=Todd |first1=Chuck |last2=Bronston |first2=Sally |last3=Rivera |first3=Matt |title=Rep. John Lewis: 'I don't see Trump as a legitimate president' |url=http://www.nbcnews.com/meet-the-press/john-lewis-trump-won-t-be-legitimate-president-n706676 |work=NBC News |date=January 14, 2017 |access-date=July 18, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170113233912/http://www.nbcnews.com/meet-the-press/john-lewis-trump-won-t-be-legitimate-president-n706676|archive-date=January 13, 2017|url-status=live}}</ref> He added, "I think the Russians participated in having this man get elected, and they helped destroy the candidacy of Hillary Clinton. I don't plan to attend the [[Inauguration of Donald Trump|Inauguration]]. I think there was a [[Russian interference in the 2016 United States elections|conspiracy on the part of the Russians]], and others, that helped him get elected. That's not right. That's not fair. That's not the open, democratic process."<ref>{{cite news| first=Nicholas| last=Loffredo| url=http://www.newsweek.com/john-lewis-trump-legitimacy-dems-skipping-inauguration-542819| title=John Lewis, Questioning Trump's Legitimacy, Among Dems Skipping Inauguration| archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170114211654/http://www.newsweek.com/john-lewis-trump-legitimacy-dems-skipping-inauguration-542819| archive-date=January 14, 2017| magazine=[[Newsweek]]| date=January 14, 2017}}</ref> Trump replied on [[Twitter]] the following day, suggesting that Lewis should "spend more time on fixing and helping his district, which is in horrible shape and falling apart (not to [...] mention crime infested) rather than falsely complaining about the election results," and accusing Lewis of being "All talk, talk, talk – no action or results. Sad!"<ref>{{cite web |last1=Dawsey |first1=Josh |last2=Cheney |first2=Kyle |last3=Morin |first3=Rebecca |title=Trump rips John Lewis as Democrats boycott inauguration |url=http://www.politico.com/story/2017/01/trump-john-lewis-233630 |work=Politico |date=January 14, 2017|access-date=July 18, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170115140853/http://www.politico.com/story/2017/01/trump-john-lewis-233630|archive-date=January 15, 2017|url-status=live}}</ref> Trump's statement about Lewis's district was rated as "Mostly False" by [[PolitiFact]],<ref>{{cite web |last=Qiu |first=Linda |title=Trump's exaggerated claim that John Lewis' district is 'falling apart' and 'crime infested' |url=http://www.politifact.com/truth-o-meter/statements/2017/jan/15/donald-trump/trumps-john-lewis-crime-invested-atlanta/ |work=PolitiFact |date=January 15, 2017 |accessdate=February 7, 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180206142907/http://www.politifact.com/truth-o-meter/statements/2017/jan/15/donald-trump/trumps-john-lewis-crime-invested-atlanta/|archive-date=February 6, 2018|url-status=live}}</ref> and he was criticized for attacking a civil rights leader such as John Lewis, especially one who was brutally beaten for the cause, and especially on [[Martin Luther King Jr. Day|Martin Luther King weekend]].<ref>{{cite web |last1=Smith |first1=David |title=Donald Trump starts MLK weekend by attacking civil rights hero John Lewis |url=https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2017/jan/14/donald-trump-john-lewis-mlk-day-civil-rights |accessdate=January 15, 2017 |newspaper=[[The Guardian]] |location=[[London]] |date=January 14, 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170115022142/https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2017/jan/14/donald-trump-john-lewis-mlk-day-civil-rights |archive-date=January 15, 2017 |url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="NYT_2017">{{citation |title=In Trump's Feud With John Lewis, Blacks Perceive a Callous Rival |url=https://nyti.ms/2iBjXO6 |newspaper=The New York Times |date=January 15, 2017 |accessdate=January 16, 2017 |first=Yamiche |last=Alcindor}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |newspaper=The Washington Post |date=January 15, 2017 |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-fix/wp/2017/01/15/in-feud-with-john-lewis-donald-trump-attacked-one-of-the-most-respected-people-in-america/?wpisrc=nl_most-draw14&wpmm=1 |title=In feud with John Lewis, Donald Trump attacked 'one of the most respected people in America' |first=Cleve R. |last=Wootson Jr. |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20170916140645/https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-fix/wp/2017/01/15/in-feud-with-john-lewis-donald-trump-attacked-one-of-the-most-respected-people-in-america/?wpisrc=nl_most-draw14&wpmm=1 |archive-date=September 16, 2017}}</ref> [[Senator John McCain]] acknowledged Lewis as "an American hero" but criticized him, saying: "this is not the first time that Congressman Lewis has taken a very extreme stand and condemned without any shred of evidence for doing so an incoming president of the United States. This is a stain on Congressman Lewis's reputation – no one else's."<ref>{{Cite news |url=https://www.politico.com/story/2017/01/trump-john-lewis-feud-tweets-233685 |title=Trump maintains feud with Lewis: He also boycotted Bush 43 |work=Politico |first=Nolan D. |last=McCaskill |date=January 17, 2017|access-date=August 6, 2018 |language=en|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180723212514/https://www.politico.com/story/2017/01/trump-john-lewis-feud-tweets-233685|archive-date=July 23, 2018|url-status=live}}</ref> The ''[[New York Post]]'' noted that Lewis used the "same unfounded, cookie-cutter personal attacks against Republican after Republican".<ref>{{cite web |url=https://nypost.com/2017/01/17/trump-should-shrug-off-john-lewis-cookie-cutter-insults/ |title=Trump should shrug off John Lewis' cookie-cutter insults |date=January 18, 2017 |work=[[New York Post]] |accessdate=February 25, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180723212523/https://nypost.com/2017/01/17/trump-should-shrug-off-john-lewis-cookie-cutter-insults/ |archive-date=July 23, 2018 |url-status=live}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||