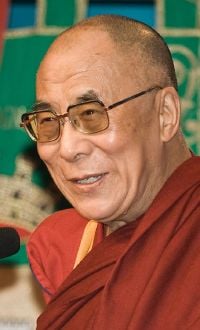

Tenzin Gyatso (born July 6, 1935) is the fourteenth Dalai Lama, and as such, is often referred to in Western media simply as the Dalai Lama, without any qualifiers. The fifth of 16 children of a farming family in the Tibetan province of Amdo, he was proclaimed the tulku (rebirth) of the thirteenth Dalai Lama at the age of two. On November 17, 1950, at the age of 15, he was enthroned as Tibet's Head of State and most important political ruler, while Tibet faced occupation by the forces of the People's Republic of China.[1]

After the collapse of the Tibetan resistance movement in 1959, Tenzin Gyatso fled to India, where he was active in establishing the Central Tibetan Administration (the Tibetan government in exile) and seeking to preserve Tibetan culture and education among the thousands of refugees who accompanied him.[2]

A charismatic figure and noted public speaker, Tenzin Gyatso is the first Dalai Lama to travel to the Western world, where he has helped to spread Buddhism and to publicize the ideal of Free Tibet. He has been an outspoken advocate of peace and tolerance and of improved relations between the religions of the world. In his writing and speaking, he has drawn on the wider Buddhist tradition, not only on Tibetan Buddhism. In 1989, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.[3] He is one of the most widely known, easily recognized and respected religious leaders in the world. He has said that when he died his political successor should be elected. Exile brought Tenzin Gyatso to the notice of a wider world. Throughout his life, he has tried to bridge barriers and has consciously communicated eastern values and Tibetan culture within the Western context.

Early Life

Gyatso was born to a farming family as Lhamo Thondup (also spelled "Dhondrub") on July 6, 1935 in far northeastern Amdo province in the village of Taktser, a small and poor settlement that stood on a hill overlooking a broad valley. His parents, Choekyong and Diki Tsering, were moderately wealthy farmers among about 20 other families making a precarious living off the land raising barley, buckwheat, and potatoes. He was the fifth surviving child of nine children; counting the children who did not survive there would have been 16 children. The eldest child of his family was his sister Tsering Dolma, who was 16 years older than he. His eldest brother, Thupten Jigme Norbu, has been recognized as the rebirth of the high lama, Takser Rinpoche. His sister Jetsun Pema went on to depict their mother in the 1997 film Seven Years in Tibet, based on the book by Heinrich Harrer. His other elder brothers are Gyalo Thondup and Lobsang Samden. When the Dalai Lama was about two years old, a search party was sent out to find the new incarnation of the Dalai Lama. Among other omens, the head on the embalmed body of the thirteenth Dalai Lama (originally facing south) had mysteriously turned to face the northeast, indicating the direction in which the next Dalai Lama would be found. Shortly afterwards, the Regent Reting Rinpoche had a vision indicating Amdo (as the place to search) and a one-story house with distinctive guttering and tiling. After extensive searching, they found that Thondup's house resembled that in Reting's vision. They thus presented Thondup with various relics and toys — some had belonged to the previous Dalai Lama while others hadn't. Thondup correctly identified all items owned by the previous Dalai Lama, stating "It's mine! It's mine!"[4]

Thondup was recognized as the rebirth of the Dalai Lama and renamed Jetsun Jamphel Ngawang Lobsang Yeshe Tenzin Gyatso ("Holy Lord, Gentle Glory, Compassionate, Defender of the Faith, Ocean of Wisdom"). He is considered to be the 14th incarnation of the Bodhisattva of Compassion. Tibetan Buddhists normally refer to him as Yeshe Norbu ("Wish-Fulfilling Gem") or just Kundun ("the Presence"). In the West he is often called by followers "His Holiness the Dalai Lama," which is the style that the Dalai Lama himself uses on his website. Tenzin Gyatso began his monastic education at the age of six. At age 11, he met an Austrian traveller named Heinrich Harrer, after spying him in Lhasa through his telescope. Harrer effectively became young Tenzin's tutor, teaching him about the outside world. The two remained friends until Harrer's death in 2006. At age 25, he sat for his final examination in Lhasa's Jokhang Temple during the annual Monlam (prayer) Festival in 1959. He passed with honors and was awarded the Lharampa degree, the highest-level geshe degree (roughly equivalent to a doctorate in Buddhist philosophy).[5]

Life as the Dalai Lama

As well as being one of the most influential spiritual leaders of Tibetan Buddhism, the Dalai Lama traditionally claims to be Tibet's Head of State and most important political ruler. At the age of 15, faced with possible conflict with the People's Republic of China, on November 17, 1950, Tenzin Gyatso was enthroned as the temporal leader of Tibet; however, he was only able to govern for a brief time. In October of that year, an army of the People's Republic of China entered the territory controlled by the Tibetan administration, easily breaking through the Tibetan defenders.

The People's Liberation Army stopped short of the old border between Tibet and Xikang and demanded negotiations. The Dalai Lama sent a delegation to Beijing, and, although he rejected the subsequent Seventeen Point Agreement for the Peaceful Liberation of Tibet, he did try to work with the Chinese government until 1959. During that year, there was a major uprising among the Tibetan population. In the tense political environment that ensued, the Dalai Lama and his entourage began to suspect that China was planning to kill him. Consequently, he fled to Dharamsala, India, on March 17 of that year, entering India on March 31 during the Tibetan uprising.

Exile in India

The Dalai Lama met with the Prime Minister of India, Jawaharlal Nehru, to urge India to pressure China into giving Tibet an autonomous government when relations with China were not proving successful. Nehru did not want to increase tensions between China and India, so he encouraged the Dalai Lama to work on the Seventeen Point Agreement Tibet had with China. Eventually in 1959, the Dalai Lama fled Tibet and set up the government of Tibet in Exile in Dharamsala, India, which is often referred to as "Little Lhasa."

After the founding of the exiled government, he rehabilitated the Tibetan refugees who followed him into exile in agricultural settlements. He created a Tibetan educational system in order to teach the Tibetan children what he believed to be traditional language, history, religion, and culture. The Tibetan Institute of Performing Arts was established in 1959, and the Central Institute of Higher Tibetan Studies became the primary university for Tibetans in India. He supported the refounding of 200 monasteries and nunneries in attempt to preserve Tibetan Buddhist teachings and the Tibetan way of life.

The Dalai Lama appealed to the United Nations on the question of Tibet, which resulted in three resolutions adopted by the General Assembly in 1959, 1961, and 1965. These resolutions required China to respect the human rights of Tibetans and their desire for self-determination. In 1963, he promulgated a democratic constitution which is based upon the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. A Tibetan parliament-in-exile is elected by the Tibetan refugees scattered all over the world, and the Tibetan Government in Exile is likewise elected by the Tibetan parliament.

At the Congressional Human Rights Caucus in 1987 in Washington, D.C., he proposed a Five-Point Peace Plan regarding the future status of Tibet. The plan called for Tibet to become a "zone of peace" and for the end of movement by ethnic Chinese into Tibet. It also called for "respect for fundamental human rights and democratic freedoms" and "the end of China's use of Tibet for nuclear weapons production, testing, and disposal." Finally, it urged "earnest negotiations" on the future of Tibet.

He proposed a similar plan at Strasbourg, France, on June 15, 1988. He expanded on the Five-Point Peace Plan and proposed the creation of a self-governing democratic Tibet, "in association with the People's Republic of China." This plan was rejected by the Tibetan Government-in-Exile in 1991. In October 1991, he expressed his wish to return to Tibet to try to form a mutual assessment on the situation with the Chinese local government. At this time he feared that a violent uprising would take place and wished to avoid it. The Dalai Lama has indicated that he wishes to return to Tibet only if the People's Republic of China sets no preconditions for the return, which they have refused to do.

The Dalai Lama celebrated his seventieth birthday on 6 July 2005. About 10,000 Tibetan refugees, monks and foreign tourists gathered outside his home. Patriarch Alexius II of the Russian Orthodox Church said, "I confess that the Russian Orthodox Church highly appreciates the good relations it has with the followers of Buddhism and hopes for their further development." President Chen Shui-bian of the Republic of China attended an evening celebrating the Dalai Lama's birthday that was entitled "Traveling with Love and Wisdom for 70 Years" at the Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall in Taipei. The President invited him to return to Taiwan for a third trip in 2005. His previous trips were in 2001, and 1997.[6]

Interreligious relations

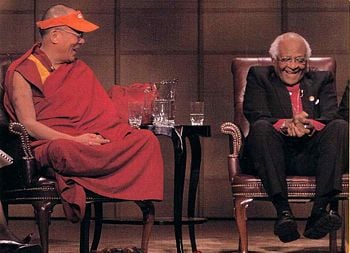

Since 1967, the Dalai Lama has initiated a series of tours in 46 nations. He has frequently engaged on religious dialogue. He met with Pope Paul VI at the Vatican in 1973. Later on, he met with Pope John Paul II in 1980 and also later in 1982, 1986, 1988, 1990 and 2003. In 1990 he met in Dharamsala with a delegation of Jewish teachers for an extensive interfaith dialogue.[7] He has since visited Israel three times, and met in 2006 with the Chief Rabbi of Israel. In 2006, he met privately with Pope Benedict XVI. He has also met the Archbishop of Canterbury, the late Dr. Robert Runcie, and with other leaders of the Anglican Church in London. He has also met with senior Eastern Orthodox Church, Muslim, Hindu, Jewish, and Sikh officials. In 2000, he was prevented from attending the UN sponsored World Summit of Religious and Spiritual Leaders because the US yielded to Chinese pressure not to grant a visa[8]. However, with Nelson Mandela he was a major contributor to the 1999 Parliament of the World's Religion at Cape Town, South Africa. At the one hundredth anniversary of the 1893 Parliament of the World's Religions in 1993 in Chicago, he delivered the closing address, when he called for harmony among the religions [9]. Alongside Desmond Tutu and other distinguished men and women, he is a patron of the World Congress of Faiths.

On Jesus

In The Good Heart (1996) the Dalai Lama pointed out that one of the differences between Buddhism and Christianity is that while a Buddha passes through many lives and stages to achieve spiritual perfection, Christians believe that Jesus was God from birth, therefore "the process of stages does not apply"[10]. However, both the Buddha and Jesus personified their teachings; Jesus not only taught the word, he was the word (76). Jesus' teaching, too, that the kingdom of God is within us sounds like the Buddhist concept of the Buddha-nature in everyone. Another difference, however, is that Buddhist's believe that the goal of the spiritual path is achieved by developing "a sense of personal responsibility," not by relying on a "transcendant being" for help (80). Yet he can see Jesus as a type of Bodhisattva who can help people along the way but points out that even in Pure Land Buddhism, in which re-birth in heaven is granted, the final step to enlightenment is achieved by self-help. Pure land is a type of university "where you practice with a teacher for a while " (128). He finds the notion, expressed by Paul Tillich of God as the "ground of being" more acceptable (73).

Social and Political Stances

Tibetan independence movement

Following the invasion the Dalai Lama had little choice but to work with the 1951 Seventeen Point Agreement for the Peaceful Liberation of Tibet with the People's Republic of China. His brothers moved to Kalimpong in India and, with the help of the Indian and American governments, organized pro-independence literature and the smuggling of weapons into Tibet. Armed struggles broke out in Amdo and Kham in 1956 and later spread to Central Tibet. However, the movement was a failure and was forced to retreat to Nepal or go underground. Following normalization of relations between the United States and the People's Republic of China, American support was cut off in the early 1970s. The 14th Dalai Lama then began to formulate his policy towards a peaceful solution in which he would be reinstated in a democratic autonomous Tibet.

Social stances

The Dalai Lama endorsed the founding of the Dalai Lama Foundation in order to promote peace and ethics worldwide. The Dalai Lama is not believed to be directly involved with this foundation.[11] He has also stated his belief that modern scientific findings take precedence over ancient religions.[12][13]

He is reported to have said regarding homosexuality, "If the two people have taken no vows [of chastity], and neither is harmed, why should it not be acceptable?" He has repeatedly affirmed his belief that gays and lesbians should be accepted by society, although he has also stated that for Buddhists homosexual behavior is considered sexual misconduct, meaning that homosexual sex is acceptable for society in general but not in Buddhism or for Buddhists.[14] He argues that what Buddhism considers wrong is the use of organs that are inappropriate for sexual contact, not sexual relations between people of the same gender per se. However, more recently he has said that the basis of this teaching was unknown to him and that he is willing to consider that some teachings of the Buddha may be for specific cultural contexts.

The Dalai Lama is generally opposed to abortion,[15] although he has taken a nuanced position, as he explained to the New York Times:

Of course, abortion, from a Buddhist viewpoint, is an act of killing and is negative, generally speaking. But it depends on the circumstances. If the unborn child will be retarded or if the birth will create serious problems for the parent, these are cases where there can be an exception. I think abortion should be approved or disapproved according to each circumstance.[16]

He has also expressed his concern for environmental problems:

- On the global level, I think the ecology problem is very serious. I hear about some states taking it very seriously. That's wonderful! So this blue planet is our only home, if something goes wrong at the present generation, then the future generations really face a lot of problems, and those problems will be beyond human control; so that's very serious. Ecology should be part of our daily life.

- — The Dalai Lama, University at Buffalo, The State University of New York, September 19, 2006[17]

In 1996, he described himself as half-Marxist, half-Buddhist:

Of all the modern economic theories, the economic system of Marxism is founded on moral principles, while capitalism is concerned only with gain and profitability. Marxism is concerned with the distribution of wealth on an equal basis and the equitable utilization of the means of production. It is also concerned with the fate of the working classes—that is the majority—as well as with the fate of those who are underprivileged and in need, and Marxism cares about the victims of minority-imposed exploitation. For those reasons the system appeals to me, and it seems fair. . . I think of myself as half-Marxist, half-Buddhist. [18]. See also the Dalai Lama's answer on various topics[19]

Criticism

In October 1998, The Dalai Lama's administration acknowledged that it received $1.7 million a year in the 1960s from the U.S. Government through the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), and also trained a resistance movement in Colorado (USA).[20] When asked by CIA officer John Kenneth Knaus in 1995 whether the organization did a good or bad thing in providing its support, the Dalai Lama replied that though it helped the morale of those resisting the Chinese, "thousands of lives were lost in the resistance" and further, that "the U.S. Government had involved itself in his country's affairs not to help Tibet but only as a Cold War tactic to challenge the Chinese."[21]

British journalist and provocateur Christopher Hitchens wrote a scathing criticism of the Dalai Lama in 1998, which questioned his alleged support for India's nuclear weapons testing, the "selling of indulgences" to Hollywood celebrities like Richard Gere, and his statements condoning prostitution.[22][23]

There has also been criticism that feudal Tibet was not as benevolent as the Dalai Lama had portrayed. Critics have suggested that in addition to serfdom there were conditions that effectively constituted slavery.[24] Also the penal code included forms of corporal punishment, in addition to capital punishment.[18] In response, the Dalai Lama has since condemned some of ancient Tibet's feudal practices and has added that he was willing to institute reforms before the Chinese invaded. However, historian Michael Parenti believes there was a connection between Dalai Lama's 1959 fleeing Tibet and the then PRC Central Government's decision to gradually phase out serfdom in Tibet.[24]

International Influence

The Dalai Lama has been successful in gaining Western sympathy for Tibetan self-determination, including vocal support from numerous Hollywood celebrities, most notably the actor Richard Gere, as well as lawmakers from several major countries.[25]

Tenzin Gyatso has on occasion been denounced by the Chinese government as a supporter of Tibetan independence. Over time, he has developed a public position stating that he is not in favor of Tibetan independence and would not object to a status in which Tibet has internal autonomy while the PRC manages some aspects of Tibet's defense and foreign affairs.[26] In his 'Middle Way Approach', he laid down that the Chinese government can take care of foreign affairs and defence, and that Tibet should be managed by an elected body.[27]

On April 18, 2005, TIME Magazine placed Tenzin Gyatso on its list of the world's 100 most influential people.[28]

On June 22, 2006, the Parliament of Canada voted unanimously to make Tenzin Gyatso an honorary citizen of Canada.[29][30] This marks the third time in history that the Government of Canada has bestowed this honor, the others being Raoul Wallenberg posthumously in 1985 and Nelson Mandela in 2001.

In September 2006, the United States Congress awarded the Dalai Lama the Congressional Gold Medal,[31] the highest award which may be bestowed by the Legislative Branch of the United States government. The decoration is awarded to any individual who performs an outstanding deed or act of service to the security, prosperity, and national interest of the United States of America. Previous winners include Nelson Mandela, George Washington, Pope John Paul II, Martin Luther King, Jr, Mother Teresa and Robert F. Kennedy.

In February 2007, the Dalai Lama was named Presidential Distinguished Professor at Emory University.[32] This was the first time that the leader of the Tibetan exile community accepted a university appointment.

Writings of the Dalai Lama

- The Art of Happiness: A Handbook for Living (coauthored with Howard C. Cutler, M.D.) NY: Riverhead Books, 1998. ISBN 9781573221115

- The Art of Happiness at Work (coauthored with Howard C. Cutler, M.D.) NY: Riverhead Books, 2003. ISBN 9781573222617

- Ethics for the New Millennium NY: Riverhead Books, 1999. ISBN 1573228834

- A Simple Path: Basic Buddhist teachings. London: Thorsons, 2000. ISBN 9780007105502

- How to Practice: The Way to a Meaningful Life, Translated and edited by Jeffrey Hopkins, Ph.D. NY: Pocket Books, 2002. ISBN 9780743427081

- Freedom in Exile: The Autobiography of the Dalai Lama. Boston: Little, Brown and Co, 1990. ISBN 034910462X

- An Open Heart: Practicing Compassion in everyday life, edited by Nicholas Vreeland. Boston: Little, Brown, 2002. ISBN 9780316989794

- The Good Heart: A Buddhist persepctive on the teachings of Jesus. Boston, MA: Wisdom Publications, 1996. ISBN 9780861711147

- The Gelug/Kagyü Tradition of Mahamudra, coauthored with Alexander Berzin. Ithaca, NY: Snow Lion Publications, 1997. ISBN 1559390727

- The Wisdom of Forgiveness: Intimate Conversations and Journeys, coauthored with Victor Chan, NY: Riverbed Books, 2004. ISBN 1573222771

- Tibetan Portrait: The Power of Compassion, photographs by Phil Borges with sayings by Tenzin Gyatso. New York: Rizzoli International Publications, 1996. ISBN 9780847819577

- The Heart of Compassion: A Practical Approach to a Meaningful Life. Twin Lakes, Wisconsin: Lotus Press, ISBN 9780940985360

- Ancient Wisdom, Modern World: Ethics for the new millenium. London: Little, Borwn, 1999. ISBN 9780316914284

- My Tibet, coauthoured with Galen Rowell, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1990. ISBN 9780520071094

- The Universe in a Single Atom: The Convergence of Science and Spirituality. NY: Morhan Road Books, 2005. ISBN 076792066X

- How to Expand Love: Widening the Circle of Loving Relationships, translated and edited by Jeffrey Hopkins, Ph.D., NY: Atria Books, 2005. ISBN 0743269683

- Der Weg des Herzens. Gewaltlosigkeit und Dialog zwischen den Religionen (The Path of the Heart: Non-violence and the Dialogue among Religions), coauthored with Eugen Drewermann, Ph.D., Solothurn: Patmos Verlag, 2003. ISBN 3491690781

- How to See Yourself As You Really Are, Translated and edited by Jeffrey Hopkins, Ph.D. NY: Atria Books, 2006. ISBN 0743290453

Awards and honors given to the Dalai Lama

The Dalai Lama has received numerous awards over his spiritual and political career.[33]On June 22, 2006 he became one of only three people ever to be recognized with an Honorary Citizenship by the Canadian House of Commons. On May 28, 2005, he received the Christmas Humphreys Award from the Buddhist Society in the United Kingdom. Perhaps his most notable award was the Nobel Peace Prize in Oslo on December 10, 1989 (see below). Some other notable awards and honors he has received:

- Presidential Distinguished Professorship from Emory University in February 2007.

- Honorary citizenship of Ukraine, during the anniversary of the Nobel Prize on December 9 2006 in Mc Leod Ganj.

- Congressional Gold Medal on September 14, 2006

- Jaime Brunet Prize for Human Rights on October 9, 2003

- Hilton Humanitarian Award on September 24, 2003

- International League for Human Rights Award on September 19, 2003

- Life Achievement Award from Hadassah Women's Zionist Organization on November 24, 1999

- Roosevelt Four Freedoms Award from the Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt Institute on June 4, 1994

- World Security Annual Peace Award from the New York Lawyer's Alliance on April 27, 1994

- Peace and Unity Awards from the National Peace conference on August 23, 1991

- Earth Prize from the United Earth and U.N. Environmental Program on June 5, 1991

- Advancing Human Liberty from the Freedom House on April 17, 1991

- Le Prix De La Memoire from the Foundation Danielle Mitterrand, France on December 4, 1989

- Raoul Wallenberg Human Rights Award from the Congressional Rights Caucus Human Rights on July 21, 1989

- Berkeley Medal from University of California, Berkeley on April 20, 1994

- Key to Los Angeles from Mayor Bradley in September 1979.

- Key to San Francisco from Mayor Feinstein on September 27, 1979

- Key to New York from Mayor Bloomberg on September 25, 2005

Nobel Peace Prize

On December 10, 1989 Tenzin Gyatso was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize,[34] the chairman of the Nobel committee saying that this was "in part a tribute to the memory of Mahatma Gandhi. The committee recognized officially his efforts in "the struggle of the liberation of Tibet and the efforts for a peaceful resolution instead of using violence." It would be, said Aarvik, "difficult to cite any historical example of a minority's struggle to secure its rights, in which a more conciliatory attitude to the adversary has been adopted than in the case of the Dalai Lama".[35] In his acceptance speech, he criticised China for the using force against student protesters during the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989. He stated however that their effort was not in vain. His speech focused on the importance of the continued use of non-violence and his desire to maintain a dialogue with China to try to resolve the situation.[36] He also paid tribute to M. K Gandhi, saying that Gandhi's life had "taught and inspired" him [37].

Films about the Dalai Lama

Among the films that have been recently made about the 14th Dalai Lama are Kundun and Seven Years in Tibet based on the book by Heinrich Harrer, (both 1997).

Other recent films include:

- Dalai Lama Renaissance (2007), documentary film about the Dalai Lama (narrated by Harrison Ford)

- Experiencing the Soul - Before Birth During Life After Death (2005)

- What Remains of Us (2004)

- Ethics for the New Millenium (DVD) (1999)

- In Search of Kundun with Martin Scorsese (1999)

- Kundun - (1998) directed by Martin Scorsese.

- Compassion In Exile (1993), documentary, directed by Mickey Lemle

See also

Notes

- ↑ "The Dalai Lama's Biography," Government of Tibet in Exile The Dalai Lama's biography.tibet.com. retrieved 15 June 2007

- ↑ Tenzin Gyatso, the Fourteenth Dalai Lama. Freedom in Exile: The Autobiography of the Dalai Lama. (NY: HarperCollins, 1990. ISBN 0060391162)

- ↑ Mary Craig. Kundun: A Biography of the Family of the Dalai Lama. (Washington, DC: Counterpoint, 1997. ISBN 1887178910)

- ↑ The Dalai Lama, "Address to the UN human rights and universal responsibility and Images of Tibet" Address to the U.N. human rights and universal responsibility, and Images of Tibet.cosmicharmony.com. retrieved 15 June 2007

- ↑ Patricia Cronin Marcello. The Dalai Lama: A Biography. (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2003. ISBN 9780313322075)

- ↑ "China keeps up attacks on Dalai Lama," CNN April 1, 2001 China Keeps up attacks on Dalia Lama. CNN retrieved 15 June 2007

- ↑ Rodger Kamenetz. The Jew in the Lotus. (NY: Harper Collins, 1994. ISBN 9780060645762)

- ↑ "Dalai Lama Inappropriate to Attend Peace Summit: Chinese Religious Leaders," August 31, 2000, Dalai Lama Inappropriate to Attend Peace Summit: Chinese Religious Leaders. World Tibet Network News, retrieved 15 June 2007

- ↑ David Briggs, "Dalai Lama Calls for Harmony Among Faiths Amid Tensions at Parliament of the World's Religions," World Tibet Network News, September 4 1993 Dalai Lama Calls for Harmony Among Faiths Amid Tensions at Parliament of the World's Religions. retrieved 15 June 2007

- ↑ Tenzin Gyatso. The Good Heart: A Buddhist perspective on the teachings of Jesus. (Boston, MT: Wisdom Publications, 1996), 118

- ↑ The Dalai Lama Foundation: Missions and Programs The Dalai Lama Foundation. retrieved 15 June 2007

- ↑ Jeffery Paine, "The Buddha of suburbia: The Dalai Lama's American religion," 09-14-2003 The Buddha of Suburbia: The Dalai Lama's American religion. The Boston Globe. retrieved 15 June 2007

- ↑ Tenzin Gyatso, "Our Faith in Science," November 12, 2005, Our Faith in Science. The New York Times retrieved 15 June 2007

- ↑ "The Buddhist Religion and homosexuality," Religious Tolerance.org The Buddhist religion and homosexuality retrieved 15 June 2007

- ↑ Garry Stivers, "Dalai Lama meets Idaho’s religious leaders," September 15, 2005, Dalai Lama meets Idaho’s religious leaders. Sun Valleyonline retrieved 15 June 2007

- ↑ Claudia Dreifus, "New York Times Interview with the Dalai Lama," November 28, 1993, New York Times Interview with the Dalai Lama. New York Times retrieved 15 June 2007

- ↑ The 14th Dalai Lama, "Address to the University of Buffalo," Internet Archive.org His Holiness the Dalai Lama's Address to the University at Buffalo retrieved 15 June 2007

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Michael Parenti, "Friendly Feudalism: The Tibet Myth," December 27, 2003, Friendly Feudalism: The Tibet Myth. Dissident Voice.org retrieved 15 June 2007

- ↑ The Dalai Lama "Tibet and China, Marxism, Nonviolence," Tibet and China, Marxism, Nonviolence.dharmakara.net. retrieved 15 June 2007

- ↑ "World News Briefs; Dalai Lama Group Says It Got Money From C.I.A," October 2, 1998,World News Briefs; Dalai Lama Group Says It Got Money From C.I.A.. New York Times retrieved 15 June 2007

- ↑ "Rogue State: A guide to the World's Only Superpower", Rogue State: A Guide to the World's Only Superpower retrieved 15 June 2007

- ↑ Christopher Hitchens, "His Material highness," Salon Table Talk, July 13, 1998, His material highness retrieved 15 June 2007

- ↑ "His Holiness the Dalai Lama's view on India's nuclear Tests," World Tibet Network News, May 20, 1998, His Holiness the Dalai Lama's views on India's nuclear teststibet.ca. retrieved 15 June 2007

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Alexander M. Lemberg, "Regarding Michael Parenti's Friendly Feudalism: The Tibet Myth," July 9 2003, Regarding Michael Parenti's Friendly Feudalism: The Tibet Myth.swans.com. retrieved 15 June 2007

- ↑ Hanna Gatner, "Indepth: The Dalai Lama," April 16, 2004, Indepth: The Dalai Lama. CBC News. retrieved 15 June 2007

- ↑ Johann Hari, "Johann Interviews the Dalai Lama," 07 06 2004 Johann Interview the Dalai Lama. The Independent retrieved 15 June 2007

- ↑ "Introduction to the Middle Way - Policy and Its History," Tibetan Bulletin (July-August 2005) 9 (4)Introduction to the Middle-Way Policy and its History. retrieved 15 June 2007

- ↑ Richard Gere, "The Dalai Lama: He Belongs to the World," in "The 2005 TIME 100" April 18, 2005The Dalai Lama: He Belongs to the World. TIME retrieved 15 June 2007

- ↑ "Dalai Lama Becomes Honorary Citizen" Victorian Times Colonist September 10, 2006 Dalai Lama becomes honorary citizen. retrieved 15 June 2007

- ↑ Karina Grudnikov, "Dalai Lama joins Wallenberg as Honorary citizen of Canada" Dalai Lama joins Wallenberg as Honorary citizen of Canada. The International Raoul Wallenberg Foundation retrieved 15 June 2007

- ↑ "Highest US Civilian Honour for Dalai Lama," 14 September 2004 Highest US civilian honour for Dalai Lama. The Times of India retrieved 15 June 2007

- ↑ Nancy Seideman, "Dalai Lama named Emory distinguished professor," February 5, 2007, Dalai Lama named Emory distinguished professor. Emory Report retrieved 15 June 2007

- ↑ List of awards

- ↑ Presentation Speech by Egil Aarvik, Chairman of the Norwegian Nobel Committee.nobelprize.org. Retrieved October 19, 2008.

- ↑ Egil Arvik, "Presentation Speech: Nobel Peace Prize, 1989", Presentation Speech.nobelprize.org. retrieved 16 June 2007

- ↑ University Aula, Oslo, December 10, 1989, His Holiness the Dalai Lama's Nobel Prize acceptance speech. The Government of Tibet in Exile Retrieved October 19, 2008.

- ↑ Tenzin Gyastso, "Nobel Lecture" December 10, 1989 Nobel Lecture.tibet.com. retrieved 16 June 2007

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Craig, Mary. Kundun: A Biography of the Family of the Dalai Lama. Washington, DC: Counterpoint, 1997. ISBN 1887178910

- Cutler, H. "THE DALAI LAMA: THE MINDFUL MONK This humble man is bridging the gap between Eastern wisdom and Western psychology," Psychology Today 34 (part 3), 34-39, 2009 ISSN 0033-3107

- Goldstein, Melvyn C. The Snow Lion and the Dragon China, Tibet, and the Dalai Lama. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1999. ISBN 9780585087030

- Gyatso, Tenzin, the Fourteenth Dalai Lama. Freedom in Exile: The Autobiography of the Dalai Lama. NY: HarperCollins, 1990. ISBN 0060391162

- Gyatso, Tenzin. The Good Heart: A Buddhist perspective on the teachings of Jesus. Boston, MA: Wisdom Publications, 1996.

- Harrer, Heinrich. Seven Years in Tibet. Tarcher, 1997. ISBN 0874778883

- Kamenetz, Rodger. The Jew in the Lotus. NY: Harper Collins, 1994. ISBN 9780060645762

- Laird, Thomas, and Bstan-ʼdzin-rgya-mtsho. The Story of Tibet: Conversations with the Dalai Lama. NY: Grove Press, 2006. ISBN 9780802118271

- Marcello, Patricia Cronin. The Dalai Lama: A Biography. (Greenwood biographies) Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2003. ISBN 9780313322075

- Perez, Louis G. The Dalai Lama. (Rourke biographies) Vero Beach, Fla: Rourke Publications, 1993. ISBN 9780866254809

- Piburn, Sidney. The Dalai Lama, a Policy of Kindness: An Anthology of Writings by and About the Dalai Lama. Ithaca, NY, USA: Snow Lion Publications, 1990. ISBN 9780937938911

External links

All links retrieved April 29, 2023.

| |||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.