|

|

| (135 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) |

| Line 1: |

Line 1: |

| | + | {{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Approved}}{{Copyedited}} |

| | + | [[File:Delphi BW 2017-10-08 11-38-38.jpg|thumb|400px|Tourists at the [[Temple of Apollo (Delphi)|Temple of Apollo]], Delphi, Greece]] |

| | + | '''Tourism''' is essentially defined as [[travel]] for pleasure, either [[Domestic tourism|domestically]] (within the traveler's own country) or [[International tourism|internationally]]. Tourism is not only an individual or group activity for the enjoyment of the travelers, but has economic implications. The commercial activity of providing and supporting such travel is a significant source of revenue for many locations and enterprises. |

| | | | |

| − | | + | Tourism often has significant environmental and social impacts that are not always beneficial to local communities and their economies. For this reason, many tourist development organizations have begun to focus on [[sustainable tourism]] to mitigate the negative effects caused by the growing impact of tourism. |

| − | [[File:Delphi BW 2017-10-08 11-38-38.jpg|thumb|upright=1.5|Tourists at the [[Temple of Apollo (Delphi)|Temple of Apollo]], Delphi, Greece]]

| + | {{toc}} |

| − | '''Tourism''' is [[travel]] for pleasure, and the commercial activity of providing and supporting such travel.<ref>{{OED|tourism}}</ref> <!-- Following sentence content duplicated traditional: Tourism may be international or within the traveler's country. —> [[World Tourism Organization|UN Tourism]] defines tourism more generally, in terms which go "beyond the common perception of tourism as being limited to holiday activity only", as people "travelling to and staying in places outside their usual environment for not more than one consecutive year for [[leisure]] and not less than 24 hours, business and other purposes".<ref name="unwto1034">{{cite web|year= 1995 |url= http://pub.unwto.org/WebRoot/Store/Shops/Infoshop/Products/1034/1034-1.pdf |title= UNWTO technical manual: Collection of Tourism Expenditure Statistics |page= 10 |publisher= World Tourism Organization |access-date= 26 March 2009 |url-status= dead |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20100922120940/http://pub.unwto.org/WebRoot/Store/Shops/Infoshop/Products/1034/1034-1.pdf |archive-date= 22 September 2010 }}</ref> Tourism can be [[Domestic tourism|domestic]] (within the traveller's own country) or [[International tourism|international]], and international tourism has both incoming and outgoing implications on a country's [[balance of payments]].

| + | Tourism has reached new dimensions with the emerging industry of [[space tourism]], as well as the [[cruise ship]] industry. Another potential new tourism industry is virtual tourism. Tourism satisfies the human desire to experience more than just daily life in one's usual location. Whether it provides an education about history, art, culture, or the wonders of nature, involving travel of only a short distance or into space, the experience is a source of joy and unforgettable stimulation to the tourist. |

| − | | |

| − | Tourism numbers declined as a result of a strong economic slowdown (the [[late-2000s recession]]) between the second half of 2008 and the end of 2009, and in consequence of the outbreak of the 2009 [[2009 flu pandemic|H1N1 influenza virus]],<ref name="Barom2009">{{cite journal|date=January 2009|title=International tourism challenged by deteriorating global economy|url=http://www.unwto.org/facts/eng/pdf/barometer/UNWTO_Barom09_1_en.pdf|url-status=dead|journal=UNWTO World Tourism Barometer|volume=7|issue=1|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131017212434/http://www2.unwto.org/facts/eng/pdf/barometer/UNWTO_Barom09_1_en.pdf|archive-date=17 October 2013|access-date=17 November 2011}}</ref><ref name="WTOaugust10">{{cite journal|date=August 2010|title=UNWTO World Tourism Barometer Interim Update|url=http://www.unwto.org/facts/eng/pdf/barometer/UNWTO_Barom10_update_august_en.pdf|url-status=dead|journal=UNWTO World Tourism Barometer|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131017203915/http://www2.unwto.org/facts/eng/pdf/barometer/UNWTO_Barom10_update_august_en.pdf|archive-date=17 October 2013|access-date=17 November 2011}}</ref> but slowly recovered until the [[COVID-19 pandemic]] put an abrupt end to the growth. The [[United Nations World Tourism Organization]] estimated that global international tourist arrivals might have decreased by 58% to 78% in 2020, leading to a potential loss of US$0.9–1.2 trillion in [[international tourism]] receipts.<ref>{{cite web|title=International Tourist Numbers Could Fall 60-80% in 2020|url=https://www.unwto.org/news/covid-19-international-tourist-numbers-could-fall-60-80-in-2020|access-date=16 September 2020|website=www.unwto.org}}</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | Globally, international tourism receipts (the travel item in the [[balance of payments]]) grew to {{USD|1.03}} trillion ({{euro|740}} billion) in 2005, corresponding to an increase in [[Real versus nominal value (economics)|real terms]] of 3.8% from 2010.<ref name="pr12027">{{Cite book|title= UNWTO Tourism Highlights: 2017 Edition|date= 1 July 2017|publisher= World Tourism Organization (UNWTO)|isbn= 978-92-844-1902-9|language=en|doi= 10.18111/9789284419029|url= https://tede.ufrrj.br/jspui/handle/jspui/5202|last1= Magalhães|first1= Bianca dos Santos}}</ref> International tourist arrivals surpassed the milestone of 1 billion tourists globally for the first time in 2012.<ref name="Barom2012">{{cite journal|date=January 2013|title=UNWTO World Tourism Barometer|url=http://dtxtq4w60xqpw.cloudfront.net/sites/all/files/pdf/unwto_barom13_01_jan_excerpt_0.pdf|url-status=dead|journal=UNWTO World Tourism Barometer|volume=11|issue=1|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130228162347/http://dtxtq4w60xqpw.cloudfront.net/sites/all/files/pdf/unwto_barom13_01_jan_excerpt_0.pdf|archive-date=28 February 2013|access-date=9 April 2013}}</ref> [[emerging markets|Emerging source markets]] such as [[China]], [[Russia]], and [[Brazil]] had significantly increased their spending over the previous decade.<ref name="Barom201304">{{cite web|url= http://media.unwto.org/en/press-release/2013-04-04/china-new-number-one-tourism-source-market-world|title= China – the new number one tourism source market in the world|publisher= [[World Tourism Organization]]|date= 4 April 2013|access-date= 9 April 2013|archive-date= 8 April 2013|archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20130408071943/http://media.unwto.org/en/press-release/2013-04-04/china-new-number-one-tourism-source-market-world|url-status= dead}}</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | Global tourism accounts for {{circa}} 8% of global [[greenhouse-gas]] emissions.<ref>

| |

| − | {{cite journal

| |

| − | | last1 = Lenzen

| |

| − | | first1 = Manfred

| |

| − | | last2 = Sun

| |

| − | | first2 = Ya-Yen

| |

| − | | last3 = Faturay

| |

| − | | first3 = Futu

| |

| − | | last4 = Ting

| |

| − | | first4 = Yuan-Peng

| |

| − | | last5 = Geschke

| |

| − | | first5 = Arne

| |

| − | | last6 = Malik

| |

| − | | first6 = Arunima

| |

| − | | title = The carbon footprint of global tourism

| |

| − | | journal = Nature Climate Change

| |

| − | | publisher = Springer Nature Limited

| |

| − | | date = 7 May 2018

| |

| − | | volume = 8

| |

| − | | issue = 6

| |

| − | | pages = 522–528

| |

| − | | issn = 1758-6798

| |

| − | | quote = [...] between 2009 and 2013, tourism's global carbon footprint has increased from 3.9 to 4.5 GtCO2e, four times more than previously estimated, accounting for about 8% of global greenhouse gas emissions. Transport, shopping and food are significant contributors. The majority of this footprint is exerted by and in high-income countries.

| |

| − | | doi = 10.1038/s41558-018-0141-x

| |

| − | | bibcode = 2018NatCC...8..522L

| |

| − | | s2cid = 90810502

| |

| − | }}

| |

| − | </ref> Emissions as well as other [[Impacts of tourism|significant environmental and social impacts]] are not always beneficial to local communities and their economies. For this reason, many tourist development organizations have begun to focus on [[sustainable tourism]] to mitigate the negative effects caused by the growing impact of tourism. The [[United Nations World Tourism Organization]] emphasized these practices by promoting tourism as part of the [[Sustainable Development Goals]], through programs like the [[International Year for Sustainable Tourism for Development]] in 2017,<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/book/10.18111/9789284419340|title=Tourism and the Sustainable Development Goals – Journey to 2030, Highlights|date=2017-12-18|publisher=World Tourism Organization (UNWTO)|isbn=978-92-844-1934-0|language=en|doi=10.18111/9789284419340}}</ref> and programs like [[Travel for SDGs|Tourism for SDGs]] focusing on how [[Sustainable Development Goal 8|SDG 8]], [[Sustainable Development Goal 12|SDG 12]] and [[Sustainable Development Goal 14|SDG 14]] implicate tourism in [[Sustainable development|creating a sustainable economy]].<ref>{{Cite web|title=Tourism & Sustainable Development Goals – Tourism for SDGs|url=http://tourism4sdgs.org/tourism-for-sdgs/tourism-and-sdgs/|access-date=2021-01-10}}</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | Tourism has reached new dimensions with the emerging industry of [[space tourism]], as well as the cruise ship industry. Another potential new tourism industry is virtual tourism. | |

| | | | |

| | ==Etymology== | | ==Etymology== |

| − | The [[English-language]] word ''tourist'' was used in 1772<ref>{{cite journal|last1= Griffiths|first1= Ralph|author-link1=Ralph Griffiths|author2=Griffiths, G.E. |title=Pennant's Tour in Scotland in 1769|journal=[[Monthly Review (London)|The Monthly Review, Or, Literary Journal]]|year= 1772|volume= 46|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=xS8oAAAAYAAJ&q=tourist&pg=PA150|access-date=23 December 2011 |page=150}}</ref> and ''tourism'' in 1811.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?allowed_in_frame=0&search=tour&searchmode=none|title= tour (n.)|first1= Douglas|last1= Harper|author-link1=Douglas Harper|work=[[Online Etymology Dictionary]]|access-date=23 December 2011}}</ref><ref>{{oed | tourism}}</ref> These words derive from the word ''tour'', which comes from Old English {{Lang|ang|turian}}, from Old French {{Lang|fro|torner}}, from Latin {{Lang|la|tornare}} - "to turn on a lathe", which is itself from Ancient Greek {{Lang|grc|tornos}} ({{Lang|grc|τόρνος}}) - "lathe".<ref>{{Cite web|url= http://etymonline.com/index.php?term=turn&allowed_in_frame=0|title= Online Etymology Dictionary|website= etymonline.com|access-date= 3 June 2016}}</ref> | + | The [[English-language]] word ''tourist'' was used in 1772<ref>Ralph Griffiths, [https://books.google.com/books?id=xS8oAAAAYAAJ&q=tourist&pg=PA150#v=snippet&q=tourist&f=false Pennant's Tour in Scotland in 1769] ''The Monthly Review, Or, Literary Journal'' 46 (1772): 150. Retrieved June 21, 2024. </ref> and ''tourism'' in 1811 to mean "travelling for pleasure."<ref name=HarperPleasure>Douglas Harper, [https://www.etymonline.com/word/tourism#etymonline_v_25855 tourism (n.)] ''Online Etymology Dictionary''. Retrieved June 21, 2024.</ref> These words derive from the word ''tour'', which comes from Old English {{Lang|ang|turian}}, from Old French {{Lang|fro|torner}}, from Latin {{Lang|la|tornare}} - "to turn on a lathe," which is itself from Ancient Greek {{Lang|grc|tornos}} ({{Lang|grc|τόρνος}}) - "lathe."<ref>Douglas Harper, [https://www.etymonline.com/word/turn turn (v.)] ''Online Etymology Dictionary''. Retrieved June 21, 2024.</ref> |

| | | | |

| | ==Definitions== | | ==Definitions== |

| − | In 1936, the [[League of Nations]] defined a ''foreign tourist'' as "someone traveling abroad for at least twenty-four hours". Its successor, the [[United Nations]], amended this definition in 1945, by including a maximum stay of six months.<ref name="theobald">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=9dvK2ajv7zIC&q=league+of+nations+tourism+1936&pg=PA6|title=Global Tourism|last=Theobald|first=William F.|publisher=[[Butterworth–Heinemann]]|year=1998|isbn=978-0-7506-4022-0|edition= 2nd|location=Oxford [England]|pages=6–7|oclc=40330075}}</ref> | + | Tourism is usually considered as travel for pleasure.<ref name=HarperPleasure/> Tourism typically requires the tourist to feel engaged in a genuine experience of the location they are visiting, such that the tourist can view the toured area as both authentic and different from their own lived experience.<ref>Dean Maccannell, ''The Tourist: A New Theory of the Leisure Class'' (University of California Press, 2013, ISBN 978-0520280007).</ref> |

| | + | |

| | + | In 1936, the [[League of Nations]] defined a ''foreign tourist'' as "someone traveling abroad for at least twenty-four hours." Its successor, the [[United Nations]], amended this definition in 1945, by including a maximum stay of six months. This duration of stay has been increased to one year or less by other international organizations.<ref> William F. Theobald (ed.),''Global Tourism'' (Routledge, 2004, ISBN 978-0750677899).</ref> |

| | | | |

| − | In 1941, Hunziker and Kraft defined tourism as "the sum of the phenomena and relationships arising from the travel and stay of non-residents, insofar as they do not lead to [[Permanent residency|permanent residence]] and are not connected with any earning activity."<ref name="1941define">{{cite book|title=Grundriß Der Allgemeinen Fremdenverkehrslehre|last1=Hunziker |first1=W|author-link1=Walter Hunziker|last2=Krapf|first2=K|oclc=180109383|publisher=Polygr. Verl|language=de|location=Zurich|year=1942}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|title=Tourismus-management: Tourismus-marketing Und Fremdenverkehrsplanung|year=1998|publisher=[u.a.] de Gruyter |isbn=978-3-11-015185-5|last1=Spode|first1=Hasso |author-link1=Hasso Spode|editor1-first= Günther|editor1-last= Haedrich|location=Berlin|oclc=243881885|language=de|chapter=Geschichte der Tourismuswissenschaft}}</ref> In 1976, the Tourism Society of England's definition was: "Tourism is the temporary, short-term movement of people to [[tourist destination|destinations]] outside the places where they normally live and work and their activities during the stay at each destination. It includes movements for all purposes."<ref>{{cite book|last=Beaver|first=Allan|title=A Dictionary of Travel and Tourism Terminology|year=2002|publisher=CAB International|isbn=978-0-85199-582-3|page=313|location=Wallingford |oclc=301675778}}</ref> In 1981, the International Association of Scientific Experts in Tourism defined tourism in terms of particular activities chosen and undertaken outside the home.<ref>{{cite web|title=The AIEST, its character and aims|url=http://www.aiest.org/org/idt/idt_aiest.nsf/en/index.html|author=International Association of Scientific Experts in Tourism|access-date=29 March 2008|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111126143828/http://www.aiest.org/org/idt/idt_aiest.nsf/en/index.html|archive-date=26 November 2011}}</ref>

| + | In 1976, the Tourism Society of England's definition was: "Tourism is the temporary, short-term movement of people to destinations outside the places where they normally live and work and their activities during the stay at each destination."<ref>Allan Beaver, ''A Dictionary of Travel and Tourism Terminology'' (Oxford University Press, 2006, ISBN 978-0851990200).</ref> |

| | | | |

| − | In 1994, the [[United Nations]] identified three forms of tourism in its ''Recommendations on Tourism Statistics'':<ref>{{cite journal|year=1994|title=Recommendations on Tourism Statistics|url=https://unstats.un.org/unsd/newsletter/unsd_workshops/tourism/st_esa_stat_ser_M_83.pdf|issue=83|page=5|journal=Statistical Papers|access-date=12 July 2010}}</ref> | + | In 1994, the United Nations identified three forms of tourism in its ''Recommendations on Tourism Statistics'':<ref>United Nations and World Tourism Organization, [https://unstats.un.org/unsd/newsletter/unsd_workshops/tourism/st_esa_stat_ser_M_83.pdf Recommendations on Tourism Statistics] ''Statistical Papers'' Series M No. 83, 1994. Retrieved June 24, 2024.</ref> |

| − | *[[Domestic tourism]], involving residents of the given country traveling only within this country | + | * Domestic tourism, involving residents of the given country traveling only within this country |

| − | * Inbound tourism,<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.oicstatcom.org/imgs/news/File/1050-presentations/sudan.pdf|title=ww.oicstatcom.org|access-date=19 June 2019|archive-date=12 December 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191212082310/http://www.oicstatcom.org/imgs/news/File/1050-presentations/sudan.pdf|url-status=dead}}</ref> involving non-residents traveling in the given country | + | * Inbound tourism, involving non-residents traveling in the given country |

| | * Outbound tourism, involving residents traveling in another country | | * Outbound tourism, involving residents traveling in another country |

| | | | |

| − | Other groupings derived from the above grouping:<ref name="glo">{{cite web |title=Glossary:Tourism - Statistics Explained |url=https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Glossary:Tourism |website=ec.europa.eu |access-date=17 December 2020 |date=30 October 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201030023647/https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Glossary:Tourism |archive-date=30 October 2020 }}</ref> | + | Other groupings derived from the above grouping:<ref>[https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Glossary:Tourism Glossary:Tourism - Statistics Explained] ''Eurostat Statistics Explained''. Retrieved June 24, 2024.</ref> |

| | * National tourism, a combination of domestic and outbound tourism | | * National tourism, a combination of domestic and outbound tourism |

| | * Regional tourism, a combination of domestic and inbound tourism | | * Regional tourism, a combination of domestic and inbound tourism |

| | * International tourism, a combination of inbound and outbound tourism | | * International tourism, a combination of inbound and outbound tourism |

| | | | |

| − | The terms ''tourism'' and ''travel'' are sometimes used interchangeably. In this context, travel has a similar definition to tourism but implies a more purposeful journey. The terms ''tourism'' and ''tourist'' are sometimes used pejoratively, to imply a shallow interest in the cultures or locations visited. By contrast, ''traveller'' is often used as a sign of distinction. The sociology of tourism has studied the cultural values underpinning these distinctions and their implications for class relations.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=YjLxR2H-YCYC|title=Tourists at the Taj: Performance and Meaning at a Symbolic Site|last=Edensor|first=Tim|year=1998|publisher=Psychology Press|isbn=978-0-415-16712-3|language=en}}</ref>

| + | A '''tourism product''' is defined as: |

| | + | <blockquote>a combination of tangible and intangible elements, such as natural, cultural, and man-made resources, attractions, facilities, services and activities around a specific center of interest which represents the core of the destination marketing mix and creates an overall visitor experience including emotional aspects for the potential customers. A tourism product is priced and sold through distribution channels and it has a life-cycle.<ref>[https://www.unwto.org/tourism-development-products Product Development] ''UN Tourism''. Retrieved June 24, 2024.</ref></blockquote> |

| | | | |

| − | [[File:Ōarai.jpg|thumb|The first sunrise seen from the [[torii]] gate on the sea, which is considered a sacred place ([[Ōarai, Ibaraki|Ōarai im Japan]])]]There are many varieties of tourism. Of those types, there are multiple forms of outdoor-oriented tourism. Outdoor tourism is generally categorized into nature, eco, and adventure tourism (NEAT). These categories share many similarities but also have specific unique characteristics. [[Nature tourism]] generally encompasses tourism activities that would take place outside. Nature tourism appeals to a large audience of tourists and many may not know they are participating in this form of tourism. This type of tourism has a low barrier to entry and is accessible to a large population. [[Ecotourism]] focuses on education, maintaining a social responsibility for the community and the environment, as well as centering economic growth around the local economy. Weaver describes ecotourism as [[Sustainability|sustainable]] nature-based tourism.<ref name="Weaver 2008">{{Cite book |last=Weaver |first=David B. |title=Ecotourism |date=2008 |publisher=Wiley |isbn=978-0-470-81304-1 |edition=2nd |series=Wiley Australia tourism series |location=Milton, Qld}}</ref> Ecotourism is more specific than nature tourism and works toward accomplishing a specific goal through the outdoors. Finally, we have adventure tourism. Adventure tourism is the most extreme of the categories and includes participation in activities and sports that require a level of skill or experience, risk, and physical exertion.<ref name="Weaver 2008"/> [[Adventure tourism]] often appeals less to the general public than nature and ecotourism and tends to draw in individuals who partake in such activities with limited marketing.

| + | == History == |

| | + | People have always wanted to travel, either to explore and discover new lands or simply for enjoyment. Tourism, or travel for enjoyment, has a very long history, beginning in ancient times when empires had grown and included many distant lands that excited the interest of those free to travel. In later times it became popular for wealthy young people to spend time on a "Grand Tour" of Europe, an experience that educated them about history, art, and culture. In modern times tourism became an industry, driving the local economies of many attractive locations, with ease of travel and affordability providing the general population with opportunities to experience the excitement of visiting different and distant places. |

| | | | |

| − | It is important to understand that these definitions may vary. Perceived risk in adventure tourism is subjective and may change for each individual.

| + | ===Ancient=== |

| − | | + | In ancient times, travel outside a person's local area for leisure was largely confined to wealthy classes, who at times traveled to distant parts of the world, to see great buildings and works of [[art]], learn new languages, experience new [[culture]]s, enjoy pristine nature, and to taste different [[cuisine]]s. |

| − | Examples of these tourism types.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Nature tourism

| |

| − | | |

| − | * [[Hiking]], [[walking]], [[camping]]

| |

| − | | |

| − | Ecotourism

| |

| − | | |

| − | * [[Tour guide|Guided tours]] focusing on educating, [[summer camp]]s, outdoor classes

| |

| − | | |

| − | Adventure tourism

| |

| − | | |

| − | * [[Rafting|White water rafting]], [[ice climbing]], [[mountaineering]]

| |

| − | | |

| − | ===Tourism products=== | |

| − | According to the World Tourism Organization, a tourism product is:<ref>{{cite web |title=Product Development {{!}} UNWTO |url=https://www.unwto.org/tourism-development-products |website=www.unwto.org |date=21 November 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201121130216/https://www.unwto.org/tourism-development-products |archive-date=21 November 2020 }}</ref>

| |

| − | {{blockquote |"a combination of tangible and intangible elements, such as natural, cultural, and man-made resources, attractions, facilities, services and activities around a specific center of interest which represents the core of the destination marketing mix and creates an overall visitor experience including emotional aspects for the potential customers. A tourism product is priced and sold through distribution channels and it has a life-cycle".}}

| |

| − | | |

| − | Tourism product covers a wide variety of services including:<ref>{{cite web |title=Introduction to tourism {{!}} VisitBritain |url=https://www.visitbritain.org/introduction-tourism |website=www.visitbritain.org |date=11 April 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200411175351/https://www.visitbritain.org/introduction-tourism |archive-date=11 April 2020 }}</ref>

| |

| − | * Accommodation services from low-cost [[homestay]]s to five-star hotels

| |

| − | * Hospitality services including food and beverage serving centers

| |

| − | * Health care services like massage

| |

| − | * All modes of transport, its booking and rental

| |

| − | * Travel agencies, guided tours and tourist guides

| |

| − | * Cultural services such as religious monuments, museums, and historical places

| |

| − | * Shopping

| |

| − | | |

| − | ===International tourism===

| |

| − | [[File:International-tourist-arrivals-by-world-region.svg|thumb|International tourist arrivals per year by region]]

| |

| − | International tourism is tourism that crosses national borders. [[Globalisation]] has made tourism a popular global leisure activity. The [[World Tourism Organization]] defines tourists as people "traveling to and staying in places outside their usual environment for not more than one consecutive year for leisure, business and other purposes".<ref>{{cite web |year=1995 |title=UNWTO technical manual: Collection of Tourism Expenditure Statistics |url=http://pub.unwto.org/WebRoot/Store/Shops/Infoshop/Products/1034/1034-1.pdf |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100922120940/http://pub.unwto.org/WebRoot/Store/Shops/Infoshop/Products/1034/1034-1.pdf |archive-date=22 September 2010 |access-date=26 March 2009 |publisher=World Tourism Organization |page=14}}</ref> The [[World Health Organization]] (WHO) estimates that up to 500,000 people are in flight at any one time.<ref name="theguardian.com">[https://www.theguardian.com/world/feedarticle/8477508 Swine flu prompts EU warning on travel to US]. ''The Guardian.'' 28 April 2009.</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | In 2010, international tourism reached [[US$]]919B, growing 6.5% over 2009, corresponding to an increase in [[Real versus nominal value (economics)|real terms]] of 4.7%.<ref>{{cite journal |date=June 2011 |title=UNWTO World Tourism Barometer June 2009 |url=http://mkt.unwto.org/sites/all/files/pdf/unwto_pisa_2011_1.pdf |url-status=dead |journal=UNWTO World Tourism Barometer |publisher=World Tourism Organization |volume=7 |issue=2 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111119091058/http://mkt.unwto.org/sites/all/files/pdf/unwto_pisa_2011_1.pdf |archive-date=19 November 2011 |access-date=3 August 2009}}</ref> In 2010, there were over 940 million international tourist arrivals worldwide.<ref name="WTO2011Highlights">{{cite journal |date=June 2011 |title=2011 Highlights |url=http://mkt.unwto.org/sites/all/files/docpdf/unwtohighlights11enlr.pdf |url-status=dead |journal=UNWTO World Tourism Highlights |publisher=UNWTO |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120113021355/http://mkt.unwto.org/sites/all/files/docpdf/unwtohighlights11enlr.pdf |archive-date=13 January 2012 |access-date=9 January 2012}}</ref> By 2016 that number had risen to 1,235 million, producing 1,220 billion USD in destination spending.<ref>{{Cite book |last=World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) |url=https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/book/10.18111/9789284419029 |title=UNWTO Tourism Highlights: 2017 Edition |date=2017-07-01 |publisher=World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) |isbn=978-92-844-1902-9 |doi=10.18111/9789284419029}}</ref> The COVID-19 crisis had [[Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on tourism|significant negative effects on international tourism]] significantly slowing the overall increasing trend.

| |

| − | | |

| − | International tourism has significant [[Impacts of tourism|impacts on the environment]], exacerbated in part by the [[Environmental impact of aviation|problems created by air travel]] but also by other issues, including wealthy tourists bringing lifestyles that stress local infrastructure, water and trash systems among others.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ==Basis==

| |

| − | Tourism typically requires the tourist to feel engaged in a genuine experience of the location they are visiting. According to Dean MacCannell, tourism requires that the tourist can view the toured area as both authentic and different from their own lived experience.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Maccannell |first=Dean |title=The Tourist: A New Theory of the Leisure Class |publisher=University of California Press |year=1999 |isbn=9780520218925 |edition=2nd |pages=12 |language=English}}</ref><ref name=":1">{{Cite book|title=The Amish and the Media {{!}} Johns Hopkins University Press Books|url=https://jhupbooks.press.jhu.edu/title/amish-and-media|access-date=2021-11-30|publisher=jhupbooks.press.jhu.edu|year=2016 |doi=10.1353/book.44948 |isbn=9781421419572 |last1=Nolt |first1=Steven }}</ref>{{Rp|page=113}}{{Better source needed|date=November 2021}} By viewing the "exotic," tourists learn what they themselves are not: that is, they are "un-exotic," or normal.<ref name=":1" />{{Better source needed|date=November 2021}}

| |

| | | | |

| − | According to MacCannell, all modern tourism experiences the "authentic" and "exotic" as "developmentally inferior" to the modern—that is, to the lived experience of the tourist.<ref name=":1" />{{Rp|page=114}}{{Better source needed|date=November 2021}}

| + | As early as the end of the third millennium B.C.E., kings like [[Shulgi]] of Ur (reigned from c. 2094 – c. 2046 B.C.E.), praised themselves for protecting roads and building way stations for travelers.<ref>N. Jayapalan, ''An Introduction To Tourism'' (Atlantic Publishers, 2013, ISBN 978-8171569779).</ref> Traveling for pleasure can be seen in [[Egypt]] as early on as 1500 B.C.E..<ref name=Casson> Lionel Casson, ''Travel in the Ancient World'' (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1994, ISBN 978-0801848087).</ref> |

| | | | |

| − | == History ==

| + | [[Ancient Rome|Ancient Roman]] tourists during the [[Roman Republic|Republic]] would visit [[spa]]s and coastal resorts such as [[Baiae]]. They were popular among the rich. The Roman upper class used to spend their free time on land or at sea and traveled to their ''villa urbana'' or ''villa maritima''. Numerous villas were located in [[Campania]], around [[Rome]], and in the northern part of the [[Adriatic Sea]] as in [[Barcola]] near [[Trieste]]. Greek traveler [[Pausanias (geographer)|Pausanias]] wrote his ''Description of Greece'' in the second century C.E.<ref name=Casson/> |

| − | ===Ancient===

| |

| − | {{see also|Travel literature}}Travel outside a person's local area for leisure was largely confined to wealthy classes, who at times travelled to distant parts of the world, to see great buildings and works of art, [[multilingualism|learn new languages]], experience new cultures, enjoy pristine nature and to taste different [[cuisine]]s. As early as [[Shulgi]], however, kings praised themselves for protecting roads and building way stations for travellers.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=HFWjoeVCLk0C|title=Introduction To Tourism|last=Jayapalan|first=N.|year=2001|publisher=Atlantic Publishers & Dist|isbn=978-81-7156-977-9|language=en}}</ref> Travelling for pleasure can be seen in [[Egypt]] as early on as 1500 B.C.E.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Casson|first1=Lionel|title=Travel in the Ancient World|date=1994|publisher=Johns Hopkins University Press|location=Baltimore|page=32}}</ref> [[Tourism in ancient Rome|Ancient Roman tourists]] during the [[Roman Republic|Republic]] would visit [[spa]]s and coastal resorts such as [[Baiae]]. They were popular among the rich. The Roman upper class used to spend their free time on land or at sea and travelled to their {{Lang|la|villa urbana}} or {{Lang|la|villa maritima}}. Numerous villas were located in [[Campania]], around [[Rome]] and in the northern part of the Adriatic as in [[Barcola]] near Trieste. [[Pausanias (geographer)|Pausanias]] wrote his ''Description of Greece'' in the second century AD. In [[ancient China]], nobles sometimes made a point of visiting [[Mount Tai]] and, on occasion, all [[five Sacred Mountains]].

| |

| | | | |

| | ===Medieval=== | | ===Medieval=== |

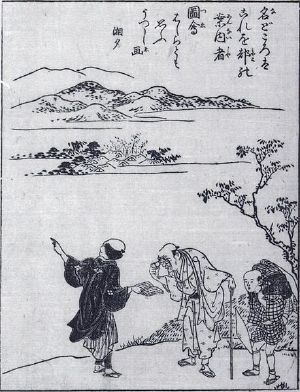

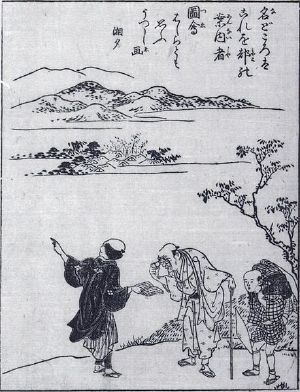

| − | [[File:"A Tour Guide to the Famous Places of the Capital" from Akizato Rito's Miyako meisho zue (1787).jpg|thumb|A Japanese tourist consulting a tour guide and a guide book from Akizato Ritō's ''Miyako meisho zue'' (1787)]]By the [[post-classical]] era, many religions, including [[Christian pilgrimage|Christianity]], [[Buddhist pilgrimage|Buddhism]], and [[Umrah|Islam]] had developed traditions of [[pilgrimage]]. ''[[The Canterbury Tales]]'' ({{Circa|1390s}}), which uses a pilgrimage as a [[framing device]], remains a classic of [[English literature]], and ''[[Journey to the West]]'' ({{Circa|1592}}), which holds a seminal place in [[Chinese literature]], has a Buddhist pilgrimage at the center of its narrative. | + | [[File:"A Tour Guide to the Famous Places of the Capital" from Akizato Rito's Miyako meisho zue (1787).jpg|thumb|300px|A Japanese tourist consulting a tour guide and a guide book from Akizato Ritō's ''Miyako meisho zue'' (1787)]] |

| | + | By the [[post-classical]] era, many religions, including [[Christianity]], [[Buddhism]], and [[Islam]] had developed traditions of [[pilgrimage]]. ''[[The Canterbury Tales]]'' ({{Circa|1390s}}), which uses a pilgrimage as a [[framing device]], remains a classic of [[English literature]], and ''[[Journey to the West]]'' ({{Circa|1592}}), which holds a seminal place in [[Chinese literature]], has a Buddhist pilgrimage at the center of its narrative. |

| | | | |

| − | In [[medieval Italy]], [[Petrarch]] wrote an allegorical account of his 1336 [[ascent of Mont Ventoux]] that praised the act of travelling and criticized {{Lang|la|frigida incuriositas}} (a 'cold lack of curiosity'); this account is regarded as one of the first known instances of travel being undertaken for its own sake.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Cassirer |first=Ernst |date=January 1943 |title=Some Remarks on the Question of the Originality of the Renaissance |jstor=2707236 |journal=Journal of the History of Ideas |publisher=University of Pennsylvania Press |volume=4 |issue=1 |pages=49–74 |doi=10.2307/2707236}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/petrarch-ventoux.asp |title=Petrarch: The Ascent of Mount Ventoux |last1=Halsall |first1=Paul |date=August 1998 |website=fordham.edu |publisher=Fordham University |access-date=5 March 2014}}</ref> The [[Duke of Burgundy|Burgundian]] poet {{Interlanguage link|Michault Taillevent|fr}} later composed his own horrified recollections of a 1430 trip through the [[Jura Mountains]].<ref>{{cite book | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=7yqsIYSNmLMC&pg=PA32 | title=Un poète bourguignon du XVe siècle, Michault Taillevent: édition et étude | publisher=Librairie Droz |author1=Deschaux, Robert |author2=Taillevent, Michault | year=1975 | pages=31–32| isbn=978-2-600-02831-8 }}</ref> | + | In [[medieval Italy]], [[Petrarch]] wrote an allegorical account of his 1336 [[ascent of Mont Ventoux]] that praised the act of traveling and criticized ''frigida incuriositas'' (a 'cold lack of curiosity'); this account is regarded as one of the first known instances of travel being undertaken for its own sake.<ref>Petrarch, [https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/source/petrarch-ventoux.asp The Ascent of Mount Ventoux] ''Medieval Sourcebook''. Retrieved June 24, 2024.</ref> The [[Duke of Burgundy|Burgundian]] poet Michault Taillevent later composed his own horrified recollections of a 1430 trip through the [[Jura Mountains]].<ref>Robert Deschaux, ''Un poète bourguignon du XVe siècle, Michault Taillevent'' (Librairie Droz, 1975, ISBN 978-2600028318).</ref> |

| | | | |

| − | In China, 'travel record literature' ({{zh|t=遊記文學|hp=yóujì wénxué|labels=no}}) became popular during the [[Song Dynasty]] (960–1279).<ref name="hargett 67">Hargett 1985, p. 67.</ref> Travel writers such as [[Fan Chengda]] (1126–1193) and [[Xu Xiake]] (1587–1641) incorporated a wealth of [[geographical]] and [[topographical]] information into their writing, while the 'daytrip essay' ''[[Su Shi#Travel record literature|Record of Stone Bell Mountain]]'' by the noted poet and statesman [[Su Shi]] (1037–1101) presented a philosophical and moral argument as its central purpose. | + | In [[China]], "travel record literature" (遊記文學; yóujì wénxué) became popular during the [[Song Dynasty]] (960–1279). Travel writers such as [[Fan Chengda]] (1126–1193) and [[Xu Xiake]] (1587–1641) incorporated a wealth of [[geographical]] and [[topographical]] information into their writing, while the 'daytrip essay' ''Record of Stone Bell Mountain'' by the noted poet and statesman [[Su Shi]] (1037–1101) presented a philosophical and moral argument as its central purpose. |

| − | <ref>{{cite journal |last1= Hargett|first1= James M. |year=1985 |title= Some Preliminary Remarks on the Travel Records of the Song Dynasty (960-1279)|journal= Chinese Literature: Essays, Articles, Reviews|volume= 7|issue= 1/2|pages=67–93 |jstor=495194 |doi= 10.2307/495194}}</ref> | + | <ref>James M. Hargett, [https://www.jstor.org/stable/495194 Some Preliminary Remarks on the Travel Records of the Song Dynasty (960-1279)] ''Chinese Literature: Essays, Articles, Reviews'' 7(1/2) (July 1985): 67–93. Retrieved June 24, 2024. </ref> |

| | | | |

| | ===Grand Tour=== | | ===Grand Tour=== |

| | {{See also|Grand Tour}} | | {{See also|Grand Tour}} |

| − | [[File:Willem van Haecht Władysław Vasa.JPG|thumb|Prince Ladislaus Sigismund of Poland visiting Gallery of [[Cornelis van der Geest]] in [[Brussels]] in 1624]] | + | [[File:Willem van Haecht Władysław Vasa.JPG|thumb|300px|Prince Ladislaus Sigismund of Poland visiting Gallery of [[Cornelis van der Geest]] in [[Brussels]] in 1624]] |

| | | | |

| − | Modern tourism can be traced to what was known as the [[Grand Tour]], which was a traditional trip around [[Europe]] (especially [[Germany]] and [[Italy]]), undertaken by mainly [[Upper class|upper-class]] European young men of means, mainly from Western and Northern European countries. In 1624, the young Prince of [[Poland]], [[Władysław IV Vasa|Ladislaus Sigismund Vasa]], the eldest son of [[Sigismund III Vasa|Sigismund III]], embarked on a journey across Europe, as was in [[Norm (sociology)|custom]] among Polish nobility.<ref name="wladcy12b">[[Tomasz Bohun]], ''Podróże po Europie'', ''Władysław IV Wasa'', Władcy Polski, p. 12</ref> He travelled through territories of today's Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, where he admired the [[Siege of Breda (1624)|siege of Breda]] by Spanish forces, France, Switzerland to Italy, Austria, and the [[Czech Republic]].<ref name="wladcy12b" /> It was an educational journey<ref>{{cite web |author=Adam Kucharski |title=Dyplomacja i turystyka – królewicz Władysław Waza w posiadłościach hiszpańskich (1624–1625) |url=http://www.wilanow-palac.art.pl/dyplomacja_i_turystyka_krolewicz_wladyslaw_waza_w_posiadlosciach_hiszpanskich_1624_1625.html |work=Silva Rerum |access-date=7 June 2017 |archive-date=14 August 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190814040300/http://www.wilanow-palac.art.pl/dyplomacja_i_turystyka_krolewicz_wladyslaw_waza_w_posiadlosciach_hiszpanskich_1624_1625.html |url-status=dead }}</ref> and one of the outcomes was introduction of [[Polish opera|Italian opera]] in the [[Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth]].<ref>''The Oxford Illustrated History of Opera'', ed. [[Roger Parker]] (1994): a chapter on Central and Eastern European opera by John Warrack, p. 240; ''The Viking Opera Guide'', ed. Amanda Holden (1993): articles on Polish composers, p. 174</ref>

| + | Contemporary tourism can be traced to what was known as the [[Grand Tour]], which was a traditional trip around [[Europe]] (especially [[Germany]], [[France]], and [[Italy]]), undertaken by [[Upper class|upper-class]] European young men of means maily from Western and Northern European countries.<ref>Carmen Périz Rodríguez, [https://www.europeana.eu/en/stories/travelling-for-pleasure-a-brief-history-of-tourism Travelling for pleasure: a brief history of tourism] ''Europeana'', June 16, 2020. Retrieved June 25, 2024.</ref> For example in 1624, the young Prince of [[Poland]], [[Władysław IV Vasa|Ladislaus Sigismund Vasa]], the eldest son of [[Sigismund III Vasa|Sigismund III]], embarked on a journey across Europe, as was in [[Norm (sociology)|custom]] among Polish nobility. It was an educational journey and one of the outcomes was the introduction of Italian [[opera]] in the [[Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth]].<ref>[https://operavision.eu/partner/polish-national-opera-and-ballet Polish National Opera and Ballet] '' Opera Vision''. Retrieved June 25, 2024.</ref> |

| | | | |

| − | The custom flourished from about 1660 until the advent of large-scale [[rail transport|rail]] transit in the 1840s and generally followed a standard [[Travel itinerary|itinerary]]. It was an educational opportunity and [[rite of passage]]. Though primarily associated with the [[British nobility]] and wealthy [[landed gentry]], similar trips were made by wealthy young men of [[Protestantism|Protestant]] [[Northern Europe]]an nations on the [[Continental Europe|Continent]], and from the second half of the 18th century some South American, US, and other overseas youth joined in. The tradition was extended to include more of the [[middle class]] after rail and steamship travel made the journey easier, and [[Thomas Cook & Son|Thomas Cook]] made the "Cook's Tour" a byword. | + | The Grand Tour became a status symbol for upper-class students in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. In this period, [[Johann Joachim Winckelmann]]'s theories about the supremacy of classic culture became very popular and appreciated in the European academic world. Artists, writers, and travelers (such as [[Goethe]]) affirmed the supremacy of classic art of which Italy, France, and Greece provide excellent examples. For these reasons, the Grand Tour's main destinations were to those centers, where upper-class students could find rare examples of classic art and history: |

| | + | <blockquote>Three hundred years ago, wealthy young Englishmen began taking a post-Oxbridge trek through France and Italy in search of art, culture and the roots of Western civilization. With nearly unlimited funds, aristocratic connections and months (or years) to roam, they commissioned paintings, perfected their language skills and mingled with the upper crust of the Continent.<ref>Matt Gross, [http://frugaltraveler.blogs.nytimes.com/2008/09/05/lesons-from-the-frugal-grand-tour/index.html Lessons From the Frugal Grand Tour] ''The New York Times'' (September 5, 2008). Retrieved June 24, 2024.</ref></blockquote> |

| | | | |

| − | The Grand Tour became a status symbol for upper-class students in the 18th and 19th centuries. In this period, [[Johann Joachim Winckelmann]]'s theories about the supremacy of classic culture became very popular and appreciated in the European academic world. Artists, writers, and travellers (such as [[Goethe]]) affirmed the supremacy of classic art of which Italy, France, and Greece provide excellent examples. For these reasons, the Grand Tour's main destinations were to those centers, where upper-class students could find rare examples of classic art and history. | + | The primary value of the Grand Tour, it was believed, laid in the exposure both to the cultural legacy of [[classical antiquity]] and the [[Renaissance]], and to the aristocratic and fashionably polite society of the European continent. The tour generally followed a standard [[Travel itinerary|itinerary]]; it was an educational opportunity and [[rite of passage]]. The custom flourished from about 1660 until the advent of large-scale [[rail transport|rail]] transit in the 1840s. Though primarily associated with the [[British nobility]] and wealthy [[landed gentry]], similar trips were made by wealthy young men of [[Protestantism|Protestant]] [[Northern Europe]]an nations on the [[Continental Europe|Continent]], and from the second half of the eighteenth century American and other overseas youth joined in. The tradition was extended to include more of the [[middle class]] after rail and steamship travel made the journey easier, and [[Thomas Cook & Son|Thomas Cook]] made the "Cook's Tour" a byword. |

| | | | |

| − | ''[[The New York Times]]'' recently described the Grand Tour in this way:

| + | ===Emergence of leisure travel=== |

| − | | + | [[File:Alsfeld-marktplatz-1900.jpg|400px|English postcard of the old town of [[Alsfeld]] in Germany, with tourists on the market square|thumb]] |

| − | {{Blockquote|text=Three hundred years ago, wealthy young Englishmen began taking a post-[[Oxbridge]] trek through France and Italy in search of art, culture and the roots of [[Western culture|Western civilization]]. With nearly unlimited funds, aristocratic connections and months (or years) to roam, they [[Commission (art)|commissioned paintings]], perfected their language skills and mingled with the upper crust of the Continent.|sign=Gross, Matt.|source=[http://frugaltraveler.blogs.nytimes.com/2008/09/05/lesons-from-the-frugal-grand-tour/index.html Lessons From the Frugal Grand Tour]." ''New York Times'' 5 September 2008.}}

| + | [[File:Banja_Slatina_ljeto.jpg|400px|The Slatina Spa in [[Slatina, Foča|Slatina]], Bosnia and Herzegovina, is famous for its characteristics and had attracted tourists since 1870s.|thumb]] |

| − | | |

| − | The primary value of the Grand Tour, it was believed, laid in the exposure both to the cultural legacy of [[classical antiquity]] and the [[Renaissance]], and to the aristocratic and fashionably polite society of the European continent. | |

| | | | |

| − | ===Emergence of leisure travel===

| + | [[Leisure]] travel was associated with the [[Industrial Revolution]] in the [[United Kingdom]]{{spaced ndash}}the first European country to promote leisure time to the increasing industrial population. Initially, this applied to the owners of the machinery of production, the economic oligarchy, factory owners, and traders. These comprised the new [[middle class]].<ref> L.K. Singh, ''Fundamental Of Tourism & Travel'' (Isha Books, 2008, ISBN 978-8182054783).</ref> [[Cox & Kings]] was the first official travel company to be formed in 1758.<ref>[https://www.coxandkings.co.uk/about-us/why-cox-kings About Us] ''Cox & Kings''. Retrieved June 25, 2024.</ref> |

| − | {{More citations needed section|date=February 2013}} | |

| − | [[File:Alsfeld-marktplatz-1900.jpg|223x223px|English postcard of the old town of [[Alsfeld]] in Germany, with tourists on the market square|thumb]]

| |

| − | [[File:Banja_Slatina_ljeto.jpg|223x223px|The Slatina Spa in [[Slatina, Foča|Slatina]], Bosnia and Herzegovina, is famous for its characteristics and had attracted tourists since 1870s.|thumb]]

| |

| | | | |

| − | [[Leisure]] travel was associated with the [[Industrial Revolution]] in the [[United Kingdom]]{{spaced ndash}}the first European country to promote leisure time to the increasing industrial population.<ref name="singh">{{cite book|last=Singh|first=L.K.|title=Fundamental of Tourism and Travel|year=2008|publisher=Isha Books|location=Delhi|isbn=978-81-8205-478-3|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=mWf4PtzRmwUC&q=the%20first%20European%20country%20to%20promote%20leisure%20time%20to%20the%20increasing%20industrial%20population&pg=PA189|page=189|chapter=Issues in Tourism Industry}}</ref> Initially, this applied to the owners of the machinery of production, the economic oligarchy, factory owners and traders. These comprised the new [[middle class]].<ref name="singh" /> [[Cox & Kings]] was the first official travel company to be formed in 1758.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.coxandkings.co.uk/aboutus-history.aspx|title=History: Centuries of Experience|publisher=[[Cox & Kings]]|access-date=23 December 2011|archive-date=25 May 2011|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110525050010/http://www.coxandkings.co.uk/aboutus-history.aspx|url-status=dead}}</ref> | + | The British origin of this new industry is reflected in many place names. In [[Nice]], France, one of the first and best-established holiday resorts on the [[French Riviera]], the long esplanade along the seafront is known to this day as the ''[[Promenade des Anglais]]''; in many other historic resorts in [[continental Europe]], old, well-established palace hotels have names like the ''Hotel Bristol'', ''Hotel Carlton'', or ''Hotel Majestic''{{spaced ndash}}reflecting the dominance of English customers. |

| | | | |

| − | The British origin of this new industry is reflected in many place names. In [[Nice]], France, one of the first and best-established holiday resorts on the [[French Riviera]], the long esplanade along the seafront is known to this day as the ''[[Promenade des Anglais]]''; in many other historic resorts in [[continental Europe]], old, well-established palace hotels have names like the ''[[Hotel Bristol]]'', ''Hotel Carlton'', or ''Hotel Majestic''{{spaced ndash}}reflecting the dominance of English customers.

| + | A pioneer of the travel agency business, [[Thomas Cook]]'s idea to offer excursions came to him while waiting for the stagecoach on the London Road at [[Kibworth]]. With the opening of the extended [[Midland Counties Railway]], he arranged to take a group of 540 [[Temperance Movement|temperance campaigners]] from [[Leicester]] to a rally in [[Loughborough]], {{convert|11|mi|km|spell=in}} away. On July 5, 1841, Thomas Cook arranged for the rail company to transport the passengers, the first time for most to have traveled by train. It was the first "package holiday" and inspired Cook to do more: “And thus was struck the keynote of my excursions, and the social idea grew upon me.” During the following three summers he planned and conducted outings for temperance societies and [[Sunday school]] children, without making any profit. This initial foray into tourism showed that if travel was convenient and accessible, people would travel beyond their familiar locale.<ref>[https://www.thomascook.com/about-us Thomas Cook's History] ''Thomas Cook''. Retrieved June 25, 2024.</ref> |

| | | | |

| − | A pioneer of the travel agency business, [[Thomas Cook]]'s idea to offer excursions came to him while waiting for the stagecoach on the London Road at [[Kibworth]]. With the opening of the extended [[Midland Counties Railway]], he arranged to take a group of 540 [[Temperance Movement|temperance campaigners]] from [[Leicester]] [[Leicester Campbell Street railway station|Campbell Street station]] to a rally in [[Loughborough]], {{convert|11|mi|km|spell=in}} away. On 5 July 1841, Thomas Cook arranged for the rail company to charge one [[shilling]] per person; this included rail tickets and food for the journey. Cook was paid a share of the fares charged to the passengers, as the railway tickets, being legal contracts between company and passenger, could not have been issued at his own price.{{clarify|date=April 2017}} This was the first privately chartered [[excursion train]] to be advertised to the general public; Cook himself acknowledged that there had been previous, unadvertised, private excursion trains.<ref>Ingle, R., 1991 ''Thomas Cook of Leicester'', Bangor, Headstart History</ref> During the following three summers he planned and conducted outings for temperance societies and [[Sunday school]] children. In 1844, the Midland Counties Railway Company agreed to make a permanent arrangement with him, provided he found the passengers. This success led him to start his own business running rail excursions for pleasure, taking a percentage of the railway fares.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.thomascook.com/thomas-cook-history/|title=Thomas Cook History|website=Thomas Cook |access-date=12 May 2017|archive-date=19 September 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180919024847/https://www.thomascook.com/thomas-cook-history/|url-status=dead}}</ref>

| + | His first commercial venture took place in the summer of 1845, when he organized a trip to Liverpool. He not only provided tickets at low prices, he printed up a brochure detailing the route. |

| | | | |

| − | In 1855, he planned his first excursion abroad, when he took a group from Leicester to [[Calais]] to coincide with the [[Exposition Universelle (1855)|Paris Exhibition]]. The following year he started his "grand circular tours" of Europe.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.thomascook.com/thomas-cook-history/key-dates/|title=Key Dates 1841–2014 |website=Thomas Cook |access-date=12 May 2017|archive-date=5 August 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170805015222/https://www.thomascook.com/thomas-cook-history/key-dates/|url-status=dead}}</ref> During the 1860s he took parties to Switzerland, Italy, Egypt, and the United States. Cook established "inclusive independent travel", whereby the traveller went independently but his agency charged for travel, food, and accommodation for a fixed period over any chosen route. Such was his success that the Scottish railway companies withdrew their support between 1862 and 1863 to try the excursion business for themselves. | + | In 1855, having organized trips all over the Britain, he planned his first excursion abroad, taking a group from Leicester to [[Calais]] to coincide with the [[Exposition Universelle (1855)|Paris Exhibition]]. The following year he started his "grand circular tours" of Europe. During the 1860s he took parties to Switzerland, Italy, Egypt, and the United States. Cook established "inclusive independent travel," whereby the traveler went independently but his agency charged for travel, food, and accommodation for a fixed period over any chosen route: a complete holiday “package.” |

| | + | <ref>[https://web.archive.org/web/20180919024847/https://www.thomascook.com/thomas-cook-history/ Thomas Cook History (archive)] ''Thomas Cook''. Retrieved June 24, 2024.</ref> |

| | | | |

| | == Economic significance of tourism == | | == Economic significance of tourism == |

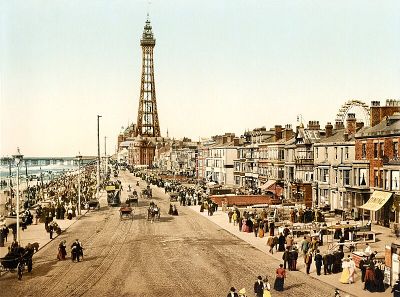

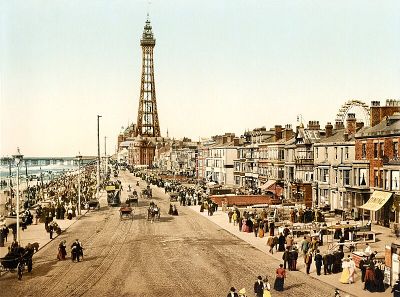

| − | [[File:The promenade, Blackpool, Lancashire, England, ca. 1898.jpg|thumb| Photochrom of the [[Blackpool]] promenade c. 1898]] | + | [[File:The promenade, Blackpool, Lancashire, England, ca. 1898.jpg|thumb|400px|Photochrom of the [[Blackpool]] promenade c. 1898]] |

| − | The tourism industry, as part of the [[service sector]],<ref> | + | The tourism industry, as part of the [[service sector]], has become an important source of income for many regions and even for entire countries.<ref> Dimitri Tassiopoulos (ed.), ''New Tourism Ventures: An Entrepreneurial and Managerial Approach'' (Juta Publishers, 2008, ISBN 978-0702177262).</ref> The ''Manila Declaration on World Tourism of 1980'' recognized its importance as "an activity essential to the life of nations because of its direct effects on the social, cultural, educational, and economic sectors of national societies, and on their international relations."<ref>[http://www.univeur.org/cuebc/downloads/PDF%20carte/65.%20Manila.PDF Manila Declaration on World Tourism] The World Tourism Conference, Manila, Philippines, September 27 to October 10, 1980. Retrieved June 25, 2024.</ref> |

| − | {{cite book |last1=Tassiopoulos| first1=Dimitri| title=New Tourism Ventures: An Entrepreneurial and Managerial Approach| publisher=Juta and Company Ltd| year=2008| isbn=9780702177262| editor1-last=Tassiopoulos| editor1-first=Dimitri| location=Cape Town| publication-date=2008| page=10}}</ref> has become an important source of income for many regions and even for entire countries. The ''Manila Declaration on World Tourism of 1980'' recognized its importance as "an activity essential to the life of nations because of its direct effects on the social, cultural, educational, and economic sectors of national societies, and on their international relations."<ref name="unwto1034"/><ref>{{cite conference|date=10 October 1980|title=Manila Declaration on World Tourism|url=http://www.univeur.org/cuebc/downloads/PDF%20carte/65.%20Manila.PDF|conference=World Tourism Conference|location=[[Manila]], [[Philippines]]|pages=1–4|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121120180003/http://www.univeur.org/CMS/UserFiles/65.%20Manila.PDF|archive-date=20 November 2012}}</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | Tourism brings large amounts of income into a local economy in the form of payment for [[goods and services]] needed by tourists, accounting {{as of | 2011 | lc = on}} for 30% of the world's [[trade]] in services, and, as an [[invisible export]], for 6% of overall [[export]]s of goods and services.<ref name="pr12027"/> It also generates opportunities for [[employment]] in the [[Tertiary sector of the economy|service sector of the economy]] associated with tourism.<ref name="WTO2012Highlights">{{cite web|date=June 2012|title=2012 Tourism Highlights|url=http://mkt.unwto.org/sites/all/files/docpdf/unwtohighlights12enlr_1.pdf|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120709215809/http://mkt.unwto.org/sites/all/files/docpdf/unwtohighlights12enlr_1.pdf|archive-date=9 July 2012|access-date=17 June 2012|publisher=UNWTO}}</ref> It is also claimed that travel broadens the mind.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.theguardian.com/education/2016/jan/18/travel-broadens-the-mind-but-can-it-alter-the-brain|website=theguardian.com|title=Travel broadens the mind, but can it alter the brain?|date=18 January 2016}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/articles/5mpgT5k3tSNsGBSc0kBD7fg/james-rebanks-one-shepherd-and-his-beloved-herdwick-sheep|quote="People think travel broadens the mind, I'm not so sure. I think a focus on, and love of, one place can make people rather sensible, decent, and wise' —James Rebanks|website=bbc.co.uk|title=James Rebanks: One shepherd and his beloved Herdwick sheep|first=James|last=Rebanks|year=2019}}</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | The hospitality industries which benefit from tourism include [[transport|transportation services]] (such as [[airline]]s, [[cruise ship]]s, [[public transport|transit]]s, [[train]]s and [[taxicab]]s); [[lodging]] (including [[hotel]]s, [[hostel]]s, [[homestay]]s, [[resort]]s and renting out rooms); and entertainment venues (such as [[amusement park]]s, [[restaurant]]s, [[casino]]s, [[festival]]s, [[shopping mall]]s, [[music venue]]s, and [[theatre]]s). This is in addition to goods bought by tourists, including [[souvenir]]s.

| |

| | | | |

| − | On the flip-side, tourism can degrade people<ref>

| + | Tourism brings large amounts of income into a local economy in the form of payment for [[goods and services]] needed by tourists. It also generates opportunities for [[employment]] in the [[Tertiary sector of the economy|service sector of the economy]] associated with tourism. |

| − | {{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Pvp_AAAAMAAJ|title=The Challenge of Tourism: Learning Resources for Study and Action|date=1990|publisher=Ecumenical Coalition on Third World Tourism|isbn=9789748555706|editor1-last=O'Grady|editor1-first=Alison|page=19|quote=[...] the products to be sold to international tourists are not only natural resources such as sea, sand and sun, but also the subservience of people in receiving countries.|access-date=20 September 2019}}

| |

| − | </ref> and sour relationships between host and guest.<ref>

| |

| − | {{cite book|last1=Smith|first1=Melanie K.|url=https://archive.org/details/issuesincultural0000smit|title=Issues in Cultural Tourism Studies|publisher=Routledge|year=2003|isbn=978-0-415-25638-4|series=Tourism / Routledge|location=London|publication-date=2003|page=[https://archive.org/details/issuesincultural0000smit/page/50 50]|quote=The globalisation of tourism has partially exacerbated the relationships of inequality and subservience that are so commonplace in host-guest encounters. It is not simply enough for local people to accept their role as servants, guides or companions to a range of ever-changing tourists. They are also confronted increasingly by the luxurious global products of Western indulgence which remain far from their reach, rather like the thirsty Tantalus in his elusive pool of water.|access-date=30 May 2018|url-access=registration}}

| |

| − | </ref> Tourism frequently also puts additional pressure on the local environment.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Gössling |first1=Stefan |last2=Hansson |first2=Carina Borgström |last3=Hörstmeier |first3=Oliver |last4=Saggel |first4=Stefan |date=2002-12-01 |title=Ecological footprint analysis as a tool to assess tourism sustainability |url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0921800902002112 |journal=Ecological Economics |language=en |volume=43 |issue=2 |pages=199–211 |doi=10.1016/S0921-8009(02)00211-2 |issn=0921-8009}}</ref>

| |

| | | | |

| − | The economic foundations of tourism are essentially the cultural assets, the [[cultural property]] and the [[nature]] of the travel location. The [[World Heritage Sites]] are particularly worth mentioning today because they are real tourism magnets. But even a country's current or former form of government can be decisive for tourism. For example, the fascination of the [[British royal family]] brings millions of tourists to Great Britain every year and thus the economy around £550 million a year. The [[Habsburg]] family can be mentioned in Central Europe. According to estimates, the Habsburg brand should generate tourism sales of 60 million euros per year for Vienna alone. The tourist principle "Habsburg sells" applies.<ref>[[Laurajane Smith]] "Uses of Heritage" (2006); Regina Bendix, Vladimir Hafstein "Culture and Property. An Introduction" (2009) in Ethnologia Europaea 39/2</ref><ref>Gerhard Bitzan, Christine Imlinger "Die Millionen-Marke Habsburg" (German), in Die Presse, 15 July 2011.</ref> | + | The hospitality industries which benefit from tourism include [[transport|transportation services]] (such as [[airline]]s, [[cruise ship]]s, [[public transport|transit]]s, [[train]]s, and [[taxicab]]s); [[lodging]] (including [[hotel]]s, [[hostel]]s, [[homestay]]s, [[resort]]s, and renting out rooms); and entertainment venues (such as [[amusement park]]s, [[restaurant]]s, [[casino]]s, [[festival]]s, [[shopping mall]]s, [[music venue]]s, and [[theatre]]s). This is in addition to goods bought by tourists, including [[souvenir]]s. |

| | | | |

| − | ==Tourism, cultural heritage and UNESCO==

| + | The economic foundations of tourism are essentially the cultural assets, the [[cultural property]], and the [[nature]] of the travel location. The [[World Heritage Sites]] are particularly worth mentioning in this context. Also, fascination with the [[British royal family]] brings millions of tourists to Great Britain every year and thus boosts the economy. The [[Habsburg]] family is a similar attraction in central Europe, particularly [[Vienna]]. |

| − | [[File:Blue Shield Fact Finding Mission Egypt.jpg|thumb|Blue Shield fact-finding mission in Egypt]] | |

| | | | |

| − | Cultural and natural heritage are in many cases the absolute basis for worldwide tourism. Cultural tourism is one of the megatrends that is reflected in massive numbers of overnight stays and sales. As [[UNESCO]] is increasingly observing, the cultural heritage is needed for tourism, but also endangered by it. The "ICOMOS - International Cultural Tourism Charter" from 1999 is already dealing with all of these problems. As a result of the tourist hazard, for example, the [[Lascaux]] cave was rebuilt for tourists. [[Overtourism]] is an important buzzword in this area. Furthermore, the focus of UNESCO in war zones is to ensure the protection of cultural heritage in order to maintain this future important economic basis for the local population. And there is intensive cooperation between UNESCO, the [[United Nations]], the [[United Nations peacekeeping]] and [[Blue Shield International]]. There are extensive international and national considerations, studies and programs to protect cultural assets from the effects of tourism and those from war. In particular, it is also about training civilian and military personnel. But the involvement of the locals is particularly important. The founding president of Blue Shield International [[Karl von Habsburg]] summed it up with the words: "Without the local community and without the local participants, that would be completely impossible'.<ref>Rick Szostak: ''The Causes of Economic Growth: Interdisciplinary Perspectives.'' Springer Science & Business Media, 2009, {{ISBN|9783540922827}}; Markus Tauschek "Kulturerbe" (2013), p 166; Laurajane Smith "Uses of Heritage" (2006).</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://portal.unesco.org/en/ev.php-URL_ID=15207&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html|title=UNESCO Legal Instruments: Second Protocol to the Hague Convention of 1954 for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict 1999}}; Roger O'Keefe, Camille Péron, Tofig Musayev, Gianluca Ferrari "Protection of Cultural Property. Military Manual." UNESCO, 2016, p 73; [https://peacekeeping.un.org/en/action-plan-to-preserve-heritage-sites-during-conflict Action plan to preserve heritage sites during conflict - UNITED NATIONS, 12 Apr 2019]</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=Austrian Armed Forces Mission in Lebanon|date=28 April 2019 |url=https://www.krone.at/1911689|language=de}}; Jyot Hosagrahar: ''Culture: at the heart of SDGs.'' UNESCO-Kurier, April-Juni 2017.</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.theguardian.com/world/shortcuts/2016/sep/27/dont-look-now-venice-tourists-locals-sick-of-you-cruise-liners |title=Don't look now, Venice tourists – the locals are sick of you |work=The Guardian |date=2016-09-27 |author=Simon Osborne |access-date=2018-05-10 |language=EN}}</ref> | + | ==Cultural heritage and tourism== |

| | + | [[File:Blue Shield Fact Finding Mission Egypt.jpg|thumb|400px|Blue Shield fact-finding mission in Egypt]] |

| | | | |

| − | ==Cruise ships==

| + | Cultural and natural heritage are in many cases the absolute basis for worldwide tourism. Cultural tourism is one of the megatrends that is reflected in massive numbers of overnight stays and sales. As [[UNESCO]] is increasingly observing, cultural heritage is needed for tourism, but also endangered by it. The "ICOMOS - International Cultural Tourism Charter" from 1999 is already dealing with all of these problems. As a result of the tourist hazard, for example, the [[Lascaux]] cave was rebuilt for tourists. |

| − | [[File:Seabourn Ovation surrounded by palm trees.jpg|thumb|The modern cruise ship ''Seabourn Ovation'' in the Mediterranean]]

| |

| − | Cruising is a popular form of [[water tourism]]. Leisure [[cruise ship]]s were introduced by the [[P&O]] in 1844, sailing from [[Port of Southampton|Southampton]] to destinations such as [[Gibraltar]], [[Malta]] and [[Athens]].<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.btnews.co.uk/article/5037|title=Ccruise News|date=June 2012|access-date=17 December 2012}}</ref> In 1891, German businessman [[Albert Ballin]] sailed the ship [[Augusta Victoria (ship)|''Augusta Victoria'']] from [[Hamburg]] into the Mediterranean Sea. 29 June 1900 saw the launching of the first purpose-built cruise ship was ''[[Prinzessin Victoria Luise]]'', built in Hamburg for the Hamburg America Line.<ref>{{Cite news|url=http://www.cruiselinehistory.com/the-prinzessin-victoria-luise-worlds-first-cruise-ship/|title=The Prinzessin Victoria Luise – world's first cruise ship|work=Cruising the Past|access-date=12 August 2018|language=en-US}}</ref>

| |

| | | | |

| | == Modern day tourism == | | == Modern day tourism == |

| | | | |

| | === Mass tourism === | | === Mass tourism === |

| − | [[File:Barceloneta 2007.jpg|thumb|Tourists at the Mediterranean Coast of [[Barcelona]] 2007]] | + | [[File:Barceloneta 2007.jpg|thumb|400px|Tourists at the Mediterranean Coast of [[Barcelona]] 2007]] |

| − | Mass tourism and its [[tourist attraction]]s have emerged as among the most iconic demonstration of western consumer societies.<ref>{{Cite book |title = Cultures of Mass Tourism: Doing the Mediterranean in the Age of Banal Mobilities | editor1 = Pau Obrador Pons | editor2= Mike Crang | editor3= Penny Travlou |year = 2016 |publisher = Taylor & Francis |page = 2 |isbn = 9781317155652 }}</ref> Academics have defined mass tourism as travel by groups on pre-scheduled tours, usually under the organization of tourism professionals. This form of tourism developed during the second half of the 19th century in the [[United Kingdom]] and was pioneered by [[Thomas Cook]]. Cook took advantage of Europe's rapidly expanding railway network and established a company that offered affordable [[day trip]] excursions to [[commoners|the masses]], in addition to longer holidays to Continental Europe, India, Asia and the Western Hemisphere which attracted wealthier customers. By the 1890s over 20,000 tourists per year used [[Thomas Cook & Son]]. | + | Mass tourism and its [[tourist attraction]]s have emerged as among the most iconic demonstration of western consumer societies.<ref> Pau Obrador Pons, Mike Crang, and Penny Travlou (eds.), ''Cultures of Mass Tourism: Doing the Mediterranean in the Age of Banal Mobilities'' (Routledge, 2009, ISBN 978-0754672135).</ref> This form of tourism developed during the second half of the nineteenth century in the [[United Kingdom]] and was pioneered by [[Thomas Cook]]. The relationship between tourism companies, transportation operators, and hotels is a central feature of mass tourism. Cook was able to offer prices that were below the publicly advertised price because his company purchased large numbers of tickets from railroads. One contemporary form of mass tourism, [[package tour]]ism, still incorporates the partnership between these three groups. |

| − | | |

| − | The relationship between tourism companies, transportation operators and hotels is a central feature of mass tourism. Cook was able to offer prices that were below the publicly advertised price because his company purchased large numbers of tickets from railroads. One contemporary form of mass tourism, [[package tour]]ism, still incorporates the partnership between these three groups. | |

| − | | |

| − | Travel developed during the early 20th century and was facilitated by the development of the automobiles and later by airplanes.

| |

| − | Improvements in transport allowed many people to travel quickly to places of leisure interest so that more people could begin to enjoy the benefits of leisure time.

| |

| | | | |

| − | In [[Continental Europe]], early [[seaside resort]]s included: [[Heiligendamm]], founded in 1793 at the [[Baltic Sea]], being the first seaside resort; [[Ostend]], popularised by the people of [[Brussels]]; [[Boulogne-sur-Mer]] and [[Deauville]] for the [[Paris]]ians; [[Taormina]] in [[Sicily]]. In the [[United States]], the first seaside resorts in the European style were at [[Atlantic City, New Jersey|Atlantic City]], [[New Jersey]] and [[Long Island]], [[New York (state)|New York]].

| + | Tourist travel developed during the early twentieth century, facilitated by the development of automobiles and later by airplanes. The improvements in transport allowed many people to travel quickly to places of leisure interest, allowing them to enjoy the benefits of leisure time in distant locations. |

| | | | |

| − | By the mid-20th century, the Mediterranean Coast became the principal mass tourism destination. The 1960s and 1970s saw mass tourism play a major role in the [[Spanish miracle#Mass tourism and emigration|Spanish economic "miracle"]]{{Citation needed|date=June 2022}}. | + | In [[Continental Europe]], early [[seaside resort]]s included: [[Heiligendamm]], founded in 1793 at the [[Baltic Sea]], being the first seaside resort; [[Ostend]], popularized by the people of [[Brussels]]; [[Boulogne-sur-Mer]] and [[Deauville]] for the [[Paris]]ians; [[Taormina]] in [[Sicily]]. In the [[United States]], the first seaside resorts in the European style were at [[Atlantic City, New Jersey|Atlantic City]], [[New Jersey]] and [[Long Island]], [[New York (state)|New York]]. By the mid-twentieth century, the Mediterranean Coast became the principal mass tourism destination. |

| | | | |

| − | In the 1960s and 1970s, scientists discussed negative socio-cultural impacts of tourism on host communities. Since the 1980s the positive aspects of tourism began to be recognized as well.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Putova |first=Barbora |date=2018 |title=Anthropology of Tourism: Researching Interactions between Hosts and Guests |url=https://sciendo.com/downloadpdf/journals/cjot/7/1/article-p71.pdf |journal=Czech Journal of Tourism |volume=7 |issue=1 |pages=71–92|doi=10.1515/cjot-2018-0004 |s2cid=159280794 }}</ref>

| + | ===Cruise ships=== |

| | + | [[File:Seabourn Ovation surrounded by palm trees.jpg|thumb|400px|The modern cruise ship ''Seabourn Ovation'' in the Mediterranean]] |

| | + | Cruising is a popular form of tourism. Leisure [[cruise ship]]s were introduced by the [[P&O]] in 1844, sailing from [[Port of Southampton|Southampton]] to destinations such as [[Gibraltar]], [[Malta]], and [[Athens]].<ref>[https://www.btnews.co.uk/article/5037 A Short History of P&O] ''BTNews'' (June 25, 2012). Retrieved June 25, 2024.</ref> In 1891, German businessman [[Albert Ballin]] sailed the ship [[Augusta Victoria (ship)|''Augusta Victoria'']] from [[Hamburg]] into the Mediterranean Sea. June 29, 1900 saw the launching of the first purpose-built cruise ship was ''[[Prinzessin Victoria Luise]]'', built in Hamburg for the Hamburg America Line.<ref>Michael Grace, [https://www.cruiselinehistory.com/the-prinzessin-victoria-luise-worlds-first-cruise-ship/ The Prinzessin Victoria Luise – world’s first cruise ship] ''Cruise The Past'', July 13, 2009. Retrieved June 25, 2024. </ref> |

| | | | |

| | ===Niche tourism=== | | ===Niche tourism=== |

| − | {{main list|List of adjectival tourisms}}

| + | [[File:Cristo Rei (36211699613).jpg|thumb|right|300px|The [[Christ the King (Almada)|Sanctuary of Christ the King]], in [[Almada]], has become one of the places most visited for religious tourism.]] |

| − | [[File:Cristo Rei (36211699613).jpg|thumb|right|The [[Christ the King (Almada)|Sanctuary of Christ the King]], in [[Almada]], has become one of the places most visited for religious tourism.]] | |

| | | | |

| − | Niche tourism refers to the numerous specialty forms of tourism that have emerged over the years, each with its own adjective. Many of these terms have come into common use by the tourism industry and academics.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Lew|first=Alan A.|title=Long Tail Tourism: New geographies for marketing niche tourism products|journal=Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing|year=2008|volume=25|issue=3–4|pages=409–19|doi=10.1080/10548400802508515|url=http://www.geog.nau.edu/publications/Long-Tail-Tourism-Lew.pdf|access-date=22 December 2011|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100614084130/http://www.geog.nau.edu/publications/Long-Tail-Tourism-Lew.pdf|archive-date=14 June 2010|citeseerx=10.1.1.467.6320|s2cid=16085592}}</ref> Others are emerging concepts that may or may not gain popular usage. Examples of the more common niche tourism markets are: | + | Niche tourism refers to the numerous specialty forms of tourism that have emerged over the years, each with its own adjective. Many of these terms have come into common use by the tourism industry and academics.<ref>Alan A. Lew, [https://www.researchgate.net/publication/255633298_Long_Tail_Tourism_New_Geographies_For_Marketing_Niche_Tourism_Products Long Tail Tourism: New geographies for marketing niche tourism products] ''Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing'' 25(3): (December 2008): 409-419. Retrieved June 25, 2024.</ref> Others are emerging concepts that may or may not gain popular usage. |

| − | {{colbegin}}

| |

| − | * [[Agritourism]]

| |

| − | * [[Birth tourism]]

| |

| − | * Coastal island tourism

| |

| − | * [[Culinary tourism]]

| |

| − | * [[Cultural tourism]]

| |

| − | * [[Dark tourism]] (also called "black tourism" or "grief tourism")

| |

| − | * [[Eco tourism]]

| |

| − | * [[Extreme tourism]]

| |

| − | * [[Film tourism]]

| |

| − | * [[Geotourism]]

| |

| − | * [[Heritage tourism]]

| |

| − | * [[LGBT tourism]]

| |

| − | * [[Medical tourism]]

| |

| − | * [[Nautical tourism]]

| |

| − | * [[Pop-culture tourism]]

| |

| − | * [[Religious tourism]]

| |

| − | * [[Sex tourism]]

| |

| − | * [[Slum tourism]]

| |

| − | * [[Sports tourism]]

| |

| − | * [[List of tallest buildings|Tallest buildings]] tourism

| |

| − | * Trains tourism (e.g., steam and model railways)

| |

| − | * [[Virtual tourism]]

| |

| − | * [[War tourism]]

| |

| − | * [[Wellness tourism]]

| |

| − | * [[Wildlife tourism]]

| |

| − | | |

| − | {{colend}}

| |

| | | | |

| | Other terms used for niche or specialty travel forms include the term "destination" in the descriptions, such as [[destination wedding]]s, and terms such as [[location vacation]]. | | Other terms used for niche or specialty travel forms include the term "destination" in the descriptions, such as [[destination wedding]]s, and terms such as [[location vacation]]. |

| | | | |

| | ===Winter tourism=== | | ===Winter tourism=== |

| − | {{See also|List of ski areas and resorts|Winter sport}}

| + | [[File:Arctic circle santa village.jpg|thumb|400px|The [[Santa Claus Village]] at the [[Arctic Circle]] in [[Rovaniemi]], Finland]] |

| − | [[File:Arctic circle santa village.jpg|thumb|The [[Santa Claus Village]] at the [[Arctic Circle]] in [[Rovaniemi]], Finland is one of the significant tourist places in the Northern Europe.<ref>{{cite web| url = https://www.discoveringfinland.com/finnish-lapland/rovaniemi/| title = Rovaniemi Lapland Holidays – Discovering Finland}}</ref>]] | |

| | | | |