Korean war

| Korean War | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Cold War | |||||||||||

United States Marines storm ashore at Incheon | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Combatants | |||||||||||

| United Nations: Republic of Korea |

Communist states: Democratic People’s Republic of Korea | ||||||||||

| Commanders | |||||||||||

| South Korea, Syngman Rhee South Korea, Chung Il Kwon |

North Korea, Kim Il-sung North Korea, Choi Yong-kun | ||||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||||

| Note: All figures may vary according to source. This measures peak strength as sizes changed during the war. South Korea 590,911 |

260,000 North Korean, | ||||||||||

| Casualties | |||||||||||

| South Koreans killed 673,000 U.S. killed 36,516 (33,686 Battle deaths) +2,830 (non-battle deaths) U.S. wounded 103,000 U.S. MIA 8,142 {see below} United Kingdom Killed 1,078 UK wounded 2,674 UK MIA/POW 1,060 Total 1,271,244 to 1,818,410 |

Chinese killed 145,000 Chinese wounded 260,000 Soviets killed 315 Total 1,858,000 to 3,822,000 | ||||||||||

| Civilians killed/wounded (total Koreans) = millions | |||||||||||

| Korean War |

|---|

| Ongjin Peninsula – Uijeongbu – Munsan – Chuncheon/Hongcheon – Gangneung – Miari – Han River – Osan – Donglakri – Danyang – Jincheon – Yihwaryeong – Daejeon – Pusan Perimeter – Inchon – Pakchon – Chosin Reservoir – Faith – Twin Tunnels – Ripper – Courageous – Tomahawk – Yultong Bridge – Imjin River – Kapyong – Bloody Ridge – Heartbreak Ridge – Sunchon – Hill Eerie – Sui-ho Dam – White Horse – Old Baldy – The Hook – Pork Chop Hill – Outpost Harry– 1st Western Sea– 2nd Western Sea |

|

Jeulmun Period

|

The Korean War, which began on June 25, 1950, and ended with a ceasefire on July 27, 1953, was a civil war between the nations of North Korea and South Korea, which were created out of the occupation zones of the Soviet Union and United States established at the end of World War II. The Soviet Union and People's Republic of China, seeking to expand the communist sphere of influence, aided the Northern Koreans, while forces from the United Nations—led primarily by the United States, and in smaller numbers the United Kingdom and Australia, aided the South Koreans. The Korean war pitted American and Soviet hardware against each other without the threat of all-out nuclear strikes (although limited nuclear strikes were discussed once the Chinese became involved).

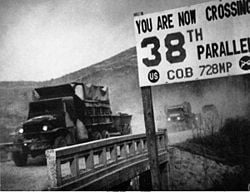

Each side wanted to unite the Korean peninsula under its own political ideology. Finally, after massive swings in favor of both the North and the South, at the end of the conflict, Korea was divided along the 38th parallel. The demilitarized zone (DMZ) between the two nations remains the most heavily fortified border in the world. And yet, movements towards unification remain prevalent in both nations. There is a constant hope among both populations that Korea will again be united under one flag.

Etymology

In South Korea, the war is often called Yuk-ee-oh (육이오/6·25), from the date of the start of the conflict or, more formally, Han-guk Jeonjaeng (Korean: 한국전쟁, literally "Korean War"). In North Korea, it is formally called the Fatherland Liberation War (Korean: 조국통일전쟁). In the United States, the conflict was officially termed a police action—the Korean Conflict—rather than a war, largely in order to avoid the necessity of a declaration of war by the U.S. Congress. The war is sometimes referred to outside Korea as "The Forgotten War," because it is a major conflict of the twentieth century that is rarely mentioned in public discourse. In China, the conflict was known as War to Resist U.S. Aggression and Aid Korea (抗美援朝), but is today commonly called the "Korean War" (朝鲜战争, Chaoxian Zhanzheng).[5]

Historical background

On August 6, 1945, the Soviet Union, in keeping with a commitment made to the United States government, declared war on the Japanese Empire, and on August 8, 1945, began an attack on the northern part of Japanese-occupied Korea. As agreed on with the U.S., the USSR halted its troops at the 38th parallel and President Harry S. Truman ordered the landing of U.S. troops in the south.[6]

On August 10, 1945, with the Japanese surrender imminent and following a plan drawn up earlier by the United States, the United States and the Soviet Union agreed to divide Korea along that 38th parallel. Japanese forces north of that line would surrender to the Soviet Union, and those to the south to the United States. Although later policies and actions contributed to Korea's division, the United States did not envision this as a permanent partition.[7]

In December 1945, the U.S. and the Soviet Union agreed to temporarily take on the administration of Korea. Concurrently, both countries established governments in their respective halves, each one favorable to their political ideology. The U.S. ran elections supervised by the UN, replacing an indigenous, left-wing government that had formed in June 1945, before the end of the war, with one led by anti-Communist Syngman Rhee. The Soviet Union, in turn, approved and furthered the rise of a Communist government led by Kim Il-Sung in the northern part.[8] In 1949, both Soviet and American forces withdrew.

South Korean President Syngman Rhee and North Korean General Secretary Kim Il-Sung were each intent on reuniting the peninsula under their own systems. Partly because of Soviet tanks and heavy arms, the North Koreans were better prepared to go on the offensive, while South Korea, with only limited American backing, had far fewer options. As for the American government, they believed at the time that the Communist bloc was a unified monolith, and that North Korea acted within this monolith as a pawn of the Soviet Union Thus, the U.S. portrayed the conflict in the context of international aggression rather than a civil war. (Kim Il-Sung, operating with some Soviet assistance, was responsible for the attack on the South.)

Rhee and Kim competed to reunite the peninsula, conducting military attacks and skirmishes along the border throughout 1949,and early 1950.[9] The North Koreans, however, armed with Soviet tanks, changed the nature of the war from a border conflict to a full blown civil war.

On January 12, 1950, United States Secretary of State Dean Acheson said that America's Pacific defense perimeter was made up of the Aleutians, Ryukyu, Japan, and the Philippines implying that the U.S. might not become involved in a fight over Korea.[10]

In mid 1949, Kim Il-Sung pressed his case with Joseph Stalin that the time had come for a reunification of the Korean peninsula. Kim needed Soviet support to successfully execute an offensive far across a rugged, mountainous peninsula. Stalin as leader of the communist bloc refused permission, concerned with the relative unpreparedness of the North Korean armed forces and with possible U.S. involvement.

Over the following year, the North Korean leadership molded the North Korean army into a formidable offensive war machine modeled partly on a Soviet mechanized force, but strengthened primarily by an influx of Koreans who had served with the Chinese People’s Liberation Army since the 1930s. By 1950, the North Koreans, equipped with Soviet weaponry, enjoyed substantial advantages over the South in every category of equipment. After another visit by Kim to Moscow in March-April of 1950, Stalin approved an attack.

The war begins

The North Korean army struck in the pre-dawn hours of Sunday, June 25, 1950, crossing the 38th parallel behind a firestorm of artillery barrage. The North Koreans attacked across a broad front, including the cities of Gaeseong, Chuncheon, Uijeongbu, and Ongjin. Within a few days, South Korean forces, outnumbered and out-gunned, were in full retreat. As the ground attack continued, the North Korean Air Force bombed Gimpo Airport near the ROK capital of Seoul. Seoul itself was captured on the afternoon of June 28, but the North Koreans failed to secure the quick surrender of the Rhee government. Kim Il-Sung had expected a quick victory, with the peasants rising up in his support. That did not happen. He did not expect the war to last long enough for American intervention, so there were no significant defenses prepared against American air attacks.

Equipped by the Soviets with 150 T-34 tanks, the North Koreans began the war with about 180 Russian aircraft, including 40 YAK fighters and 70 attack bombers. Naval support was inconsequential. North Korea's most serious weakness was the lack of a reliable logistics system for moving supplies south as the army advanced. (In practice, the regime forced thousands of civilians to hand-carry supplies, while subject to American air attacks.) Nevertheless, the North's initial attack with about 135,000 troops achieved surprise and quick successes. The invasion of South Korea came as a surprise to the United States and the other western powers. The South Korean Army had only 65,000 soldiers present for duty, and was deficient in armor and artillery. There were no large foreig, combat units in the country when the invasion began, athough there were large American forces stationed in nearby Japan.[11]

The other western powers quickly agreed with American actions, volunteering their support for the effort. By August, the South Korean forces and the U.S. Eighth Army, which had arrived to help South Korea resist the North Korean attack, had lost a lot of ground and had been driven into a small area in the southeast corner of the Korean peninsula around the city of Busan. With the aid of American air support, additional reinforcements, and supplies, the U.S. and South Korean forces managed to stabilize a line along the Nakdong River. This desperate holding action became known in the U.S. as the Pusan Perimeter. Although more UN support arrived, the situation was dire for the southern regime and its foreign allies, looking as though the North Koreans might succeed in gaining control of the entire peninsula.

Truman sends in American forces

On hearing of the invasion, President Harry S. Truman ordered General Douglas MacArthur, stationed in Japan, to use U.S. naval and air forces to stem the North Korean advance. Disagreeing with his advisors, who called for unilateral U.S. airstrikes against the North Korean forces, Truman stipulated that they were not allowed to attack north of the 38th parallel, and especially not into Chinese or Russian territory, as Truman wanted to keep the Chinese and Russians out of the conflict.

MacArthur was also to transfer munitions to the ROK Army, while using air cover to protect the evacuation of U.S. citizens. Truman also ordered the Seventh Fleet to protect the island of Taiwan. Although the Chinese Nationalists offered to participate in the war, the Americans declined not only because they were poorly equipped and trained, but also because, politically, there was a risk that Nationalist participation would encourage overt intervention by the Chinese communists. On July 5, The U.S. Army 24th Infantry Division, the first significant American combat unit to arrive in South Korea, engaged in the first North Korean-American clash of the war at Osan. The United Nations also took immediate action, ordering the invaders to withdraw and calling all members to support South Korea. A UN command was established under the control of the United States. Britain, Australia, and other Western powers quickly showed support and volunteered to aid in the effort.[12]

Pusan perimeter

By August 1950, the ROK forces and newly arrived units of the U.S. Eighth Army had been driven back into a small area in the southeastern corner of the peninsula, around the port city of Pusan. With the aid of American supplies, naval and air support, and additional reinforcements, the U.S. and ROK forces barely managed to stabilize a line along the Nakdong River. In the face of fierce North Korean attacks, the allied defense became a desperate holding action, called the Battle of Pusan Perimeter. The failure of North Korea to capture the city of Pusan itself ultimately doomed its invasion.

American air power arrived in force, flying 40 sorties a day in ground support actions, especially against tanks. Strategic bombers (mostly B-29 Superfortresses based in Japan) closed most rail and road traffic by day, and cut 32 critical bridges. The bombers knocked out the main supply dumps in the north, as well as the oil refineries and seaports that handled Russian imports. Naval air power also attacked transportation choke points. The North Korean logistics problems grew severe, with shortages of food and ammunition. The North lost half its invading force and morale was poor.

Meanwhile, supply bases in Japan were pouring weapons and soldiers into Pusan. Tank battalions were rushed in from San Francisco; by late August, the U.S. had over 500 medium tanks in the Pusan perimeter. By early September, UN-ROK forces were vastly stronger and outnumbered the North Koreans by 180,000 to 100,000. At that point, they began their counterattack.[13]

Inchon landing and move north (September–October 1950)

In order to alleviate pressure on the Pusan Perimeter, MacArthur, as UN commander-in-chief for Korea, ordered an amphibious invasion at Incheon, which was far behind the front line of the North Korean troops. This plan had been formulated by MacArthur several days after the war began, but he faced heavy resistance from the Pentagon due to the extreme risk of the operation. However, once MacArthur gained approval for his controversial strategy, it proved extremely successful. Having gained a foothold on the beach, the American troops with their UN allies faced only mild resistance and quickly moved to recapture Seoul. The North Koreans, finding their supply lines cut, began a rapid retreat northwards, allowing the ROK and UN forces that had been crowded inconfined in the south moved north and joined those that had landed at Inchon.[14]

In the face of these reinforcements, the North Koreans found themselves undermanned with weak logistical support, and lacking naval and air support. The United Nations troops drove the North Koreans back past the 38th parallel. The goal of saving South Korea had been achieved, but because of the success and the prospect of uniting all of Korea under the government of Syngman Rhee, the Americans—with UN approval—were convinced to continue into North Korea. This greatly concerned the Chinese, who worried that the UN forces would not stop at the Yalu River, the borderline between the PRK and China. Many in the West, including General MacArthur, thought that spreading the war to China would be necessary. However, Truman and the other leaders disagreed, and MacArthur was ordered to be very cautious when approaching the Chinese border. And while MacArthur argued that, because the North Korean troops were being supplied by bases in China those supply depots should be bombed, except on some rare occasions, UN bombers remained out of Manchuria during the war.

The Chinese entry (October 1950)

The People's Republic of China, fearful of a capitalist Korean state on its border, warned neutral diplomats that it would intervene. Truman regarded the warnings as "a bald attempt to blackmail the UN." On October 15, 1950, Truman went to Wake Island for a short, highly publicized meeting with MacArthur. The CIA had previously told Truman that Chinese involvement was unlikely. MacArthur, saying he was speculating, saw little risk. The general explained that the Chinese had lost their window of opportunity to help North Korea's invasion. He estimated the Chinese had 300,000 soldiers in Manchuria, with between 100,000-125,000 men along the Yalu; half could be brought across the Yalu. But the Chinese had no air force; hence, "if the Chinese tried to get down to Pyongyang there would be the greatest slaughter."[15] MacArthur, thus, assumed that Chinese were motivated to help North Korea, and wished to avoid heavy casualties.

On October 8, 1950, the day after American troops crossed the 38th, Chairman Mao issued the order for the Chinese People's Volunteer Army. It was named in that way, so it won't appear to the world that it was not a state-to-state war between China and the U.S. Those soldiers "volunteered" to fight. They were actually regulars in the Chinese People's Liberation Army. Mao ordered the army to move to the Yalu River, ready to cross. Mao sought Soviet aid and saw intervention as essentially defensive: "If we allow the U.S. to occupy all of Korea… we must be prepared for the U.S. to declare… war with China," he told Stalin. Premier Zhou Enlai was sent to Moscow to add force to Mao's cabled arguments. Mao delayed his forces while waiting for Russian help, and the planned attack was thus postponed from October 13 to October 19. Soviet assistance was limited to providing air support no nearer than sixty miles (96 km) from the battlefront. The Russian MiG-15s in PRC colors became a serious threat to the UN pilots. In one area ("MiG Alley"), they held local air superiority against the F-80 Shooting Stars until newer F-86 Sabres were deployed. The Chinese were angry at the limited support, having assumed that the Soviets had promised to provide full scale air support. The Soviet role was known to the U.S. but they kept quiet to avoid any international and potential nuclear incidents.

The Chinese made a skirmish on October 25, 1950, with 270,000 PVA troops under the command of General Peng Dehuai, much to the surprise of the UN. However, after these initial engagements, the Chinese forces melted away into the mountains. UN leaders saw the retreat as a sign of weakness, and greatly underestimated the Chinese fighting capability given limited Soviet assistance. The UN forces, thus, continued their advance to the Yalu river, ignoring stern warnings given by the Chinese to stay away.

UN retreat

In late November, the Chinese struck in the west, along the Chongchon River, and completely overran several ROK divisions and landed a heavy blow to the flank of the remaining UN forces. The resulting withdrawal of the U.S. Eighth Army was the longest retreat of any American military unit in history.[16] In the east, at the Battle of Chosin Reservoir, a 30,000 man unit from the U.S. 7th Infantry Division were soon surrounded, but eventually fought their way out of the encirclement after suffering over 15,000 casualties. The Marines, although surrounded at the Chosin Reservoir, retreated after inflicting heavy casualties on six attacking Chinese divisions.[17]

The UN forces in northeast Korea quickly withdrew to form a defensive perimeter around the port city of Hungnam, where a major evacuation was being carried out in late December 1950. Altogether, 193 shiploads of men and material were evacuated from Hungnam Harbor, and about 105,000 soldiers, 98,000 civilians, 17,500 vehicles, and 350,000 tons of supplies were shipped to Pusan in orderly fashion.[18]

Fighting across the 38th Parallel (Early 1951)

On January 4, 1951, Chinese and North Korean forces recaptured Seoul. Both the 8th Army and the X Corps were forced to retreat. The situation was so grim that MacArthur mentioned the use of atomic weapons against China, much to the alarm of America's allies.

The Chinese could not go beyond Seoul because they were at the end of their logistics supply line—all food and ammunition had to be carried—at night—on foot or bicycle from the Yalu River. On March 16, 1951, in Operation Ripper, a revitalized Eighth Army repelled the North Korean and Chinese troops from Seoul, the fourth time in a year the city had changed hands. Seoul was in utter ruins; its prewar population of 1.5 million had dropped to 200,000, with severe food shortages.[19]

MacArthur was removed from command by President Truman on April 11, 1951. The reasons for this are many and well documented. They include MacArthur's meeting with ROC President Chiang Kai-shek in the role of a U.S. diplomat; he was also wrong at Wake Island, when President Truman asked him specifically about Chinese troop buildup near the Korean border. Furthermore, MacArthur openly demanded nuclear attack on China, while being rude and flippant when speaking to Truman. Another reason why the president removed MacArthur was that he wanted a reliable commander in field should the U.S. decide to use nuclear weapons. Truman was not sure he could trust MacArthur to use nuclear weapons as ordered.

MacArthur was succeeded by Ridgway, who managed to regroup UN forces for an effective counter-offensive. A series of attacks managed to slowly drive back the opposing forces, inflicting heavy casualties on Chinese and North Korean units as UN forces advanced some miles north of the 38th parallel.

Stalemate (July 1951-July 1953)

The rest of the war involved little territory change, large scale bombing of the north, and lengthy peace negotiations. Even during the peace negotiations, combat continued. For the South Korean and allied forces, the goal was to recapture all of South Korea before an agreement was reached in order to avoid loss of any territory. The Chinese attempted a similar operation at the Battle of the Hook, where they were repelled by British forces. A major issue of the negotiations was repatriation of POWs. The Communists agreed to voluntary repatriation, but only if the majority would return to China or North Korea, something that did not occur. As many refused to be repatriated to the communist North Korea and China, the war continued until the Communists eventually dropped this issue.

On November 29, 1952, U.S. President-elect Dwight D. Eisenhower fulfilled a campaign promise by going to Korea to find out what could be done to end the conflict. With the UN's acceptance of India's proposal for a Korean armistice, a cease-fire was established on July 27, 1953, by which time the front line was back around the proximity of the 38th parallel, and so a demilitarized zone (DMZ) was established around it, still defended to this day by North Korean troops on one side and South Korean and American troops on the other. The DMZ runs north of the parallel towards the east, and to the south as it travels west. The site of the peace talks, Kaesong, the old capital of Korea, was part of the South before hostilities broke out but is currently a special city of the North. No peace treaty has been signed to date.

Western reaction

American action was taken for a number of reasons. Truman, a Democratic president, was under severe domestic pressure for being too soft on communism by. The intervention was also an important implementation of the new Truman Doctrine, which advocated the opposition of communism wherever it tried to expand. The lessons of Munich, in 1938, also influenced the American decision, believing that appeasing communism would only encourage further expansion.

Instead of pressing for a congressional declaration of war, which he regarded as too alarmist and time-consuming when time was of the essence, Truman went to the UN for approval. (He would later come under harsh criticism for not consulting Congress before sending troops.) Thanks to a temporary Soviet absence from the Security Council—the Soviets were boycotting the Security Council to protest the exclusion of People's Republic of China (PRC) from the UN—there was no veto by Stalin and the (Nationalist-controlled) Republic of China government held the Chinese seat. Without Soviet and Chinese vetoes, and with only Yugoslavia abstaining, the UN voted to aid South Korea on June 27. U.S. forces were eventually joined during the conflict by troops from 15 other UN members: Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Britain, France, South Africa, Turkey, Thailand, Greece, the Netherlands, Ethiopia, Colombia, the Philippines, Belgium, and Luxembourg. Although American opinion was solidly behind the venture, Truman would later take harsh criticism for not obtaining a declaration of war from Congress before sending troops to Korea. Thus, "Truman's War" was said by some to have violated the spirit, if not the letter, of the United States Constitution.

Legacy

The Korean War was the first armed confrontation of the Cold War and set the standard for many later conflicts. It created the idea of a limited war, where the two superpowers would fight without descending into an all-out war that could involve nuclear weapons. It also expanded the Cold War, which to that point had mostly been concerned with Europe. The war led to a strengthening of alliances in the Western bloc and the splitting of China from the Soviet bloc.

600,000 Korean soldiers died in the conflict according to U.S. estimates. About one million South Koreans were killed, 85 percent of them civilians. According to figures published in the Soviet Union, 11.1 percent of the total population of North Korea died, which indicates that around 1,130,000 people were killed. The total casualties were about 2,500,000. More than 80 percent of the industrial and public facilities and transportation infrastructure, three-quarters of all government buildings, and half of all housing was destroyed.

The war left the peninsula divided, with a communist state in North Korea and an authoritarian state in the South. Eventually, South Korea transitioned to democracy with a rapidly growing free-market economy, while North Korea stuck to its Stalinist communist roots, with totalitarian rule and a cult of personality around leaders Kim Il-sung and Kim Jong-il, under whom there has been widespread famine. American troops remain in Korea as part of the still-functioning UN Command, which commands all allied military forces in South Korea—American Air Forces, Korea, the Eighth U.S. Army, and the entire South Korean military. No significant Russian or Chinese military forces remain in North Korea today. The demilitarized zone remains the most heavily-defended border in the world. Many Korean families were also divided by the war, most of whom have had no opportunity to contact or meet one another.

Depictions

Artist Pablo Picasso's painting Massacre in Korea (1951) depicted violence against civilians during the Korean War. By some account, civilian killings committed by U.S. forces in Shinchun, Hwanghae Province was the motive of the painting. In South Korea, the painting was deemed anti-American, a longtime taboo in the South, and was prohibited for public display until the 1990s. Picasso's paintings made no allusions to Communist atrocities.

In the U.S. far and away the most famous artistic depiction of the war is M*A*S*H, originally a novel by Richard Hooker (pseudonym for H. Richard Hornberger) that was later turned into a successful movie and television series. All three versions depict the misadventures of the staff of a Mobile Army Surgical Hospital as they struggle to keep their sanity through the war's absurdities through ribald humour and hijinks when not treating wounded.

Ha Jin's War Trash contains a vivid description of the beginning of the war from the point of view of a Chinese soldier.

Films

- Fixed Bayonets (1951). U.S. soldiers in Korea surviving the harsh winter of 1951. Directed by Samuel Fuller.

- The Steel Helmet (1951). A squad of U.S. soldiers holes up in a Buddhist temple. Directed by Samuel Fuller.

- Battle Circus (1951). A love story of a hard-bitten surgeon and a new nurse at a M.A.S.H. unit. It starred Humphrey Bogart and June Allyson and was directed by Richard Brooks.

- Men of the Fighting Lady (1954). Fictional account of U.S. Navy pilots flying F9F Panther fighter jets on hazardous missions against ground targets. Directed by Andrew Marton and starring Van Johnson.

- The Bridges at Toko-Ri (1955). A U.S. Navy Reserve pilot flying attack missions over North Korea, from the novel by James Michener. Directed by Mark Robson and starring William Holden. Winner of the 1955 Academy Award for Best Special Effects.

- Target Zero (1955). U.S., British, and South Korean troops are trapped behind enemy lines.

- Shangganling Battle (Shanggan Ling, Chinese: 上甘岭, BW-1956). In the Korean war in early 1950s, a group of Chinese People's Volunteer soldiers are blocked in Shangganling mountain area for several days. Short of both food and water, they hold their ground till the relief troops arrive.

- Battle Hymn (1956). Based on the autobiography of Colonel Dean E. Hess, an American clergyman and World War II veteran fighter pilot who volunteers to return to active duty to train the fighter pilots of the South Korean Air Force. Starring Rock Hudson as Hess.

- Pork Chop Hill (1957). A true story about U.S. soldiers attempting to retake the top of a hill. Directed by Lewis Milestone and starring Gregory Peck.

- The Hunters (1958). Robert Mitchum and Robert Wagner as U.S. Air Force F-86 pilots in an adaptation of the novel by James Salter, who was himself an F-86 pilot in the Korean War.

- The Manchurian Candidate (1962). The principal characters in the film are captured and brainwashed during the war. (The 2004 remake of the movie used the Persian Gulf War of 1991 instead.)

- MASH (1970), about the staff of a U.S. Army field hospital who use humor and pranks to keep their sanity in the face of the horror of war. Directed by Robert Altman.

- M*A*S*H (1972-1983) was also a long-running television sitcom, inspired by the movie, featuring Alan Alda. The television series lasted several times longer than the war.

- Inchon (1981). The movie portrays the Battle of Incheon, a turning point in the war. Controversially, the film was partially financed by Sun Myung Moon's Unification Movement. It became a notorious financial and critical failure, losing an estimated $40 million of its $46 million budget, and remains the last mainstream Hollywood film to use the war as its backdrop. The film was directed by Terence Young, and starred an elderly Laurence Olivier as General Douglas MacArthur.

- Joint Security Area (film) (Gongdong gyeongbi guyeok JSA) (2000). In the DMZ (Korean Demilitarized Zone) separating North and South Korea, two North Korean soldiers have been killed, supposedly by one South Korean soldier. The investigating Swiss/Swedish team from the neutral countries overseeing the DMZ (Korean Demilitarized Zone) suspects from evidence at the crime scene that another, unknown party was involved. Major Sophie E. Jean, the investigating officer, suspects a cover-up is taking place, but the truth is much simpler and much more tragic. It unravels as the story follows the development of a relationship between two North Korean and two South Korean soldiers that hang out together in an empty building in the Joint Security Area. Starring Lee Young Ae, Lee Byung-Hun, Song Kang-ho, Kim Tae-woo, and Shin Ha-kyun. Directed by Park Chan-wook.

- Tae Guk Gi: The Brotherhood of War (2004). When two Korean brothers are drafted into the military to fight in the war, the older brother tries to protect the younger by risking his own life in hopes of sending his brother home. This results in an emotional conflict that wears away at his own humanity. Epic in scope, the movie has a touching family story backdropped by a brutal war. Directed by Je-Kyu Kang or Kang Je-gyu.

- Welcome to Dongmakgol (2005). During the height of the war, three North Korean soldiers, two South Korean soldiers and a U.S. Navy pilot accidentally get stranded together in a remote and peaceful mountain village paradise called Dongmakgol. All three wayward factions learn that the village is naively oblivious to the raging war outside. These newcomers must somehow find a way to coexist with each other for the sake and preservation of the village they all learn to love and respect. Directed by Park, Gwang-hyeon.

Further reading

Combat studies, soldiers

- Appleman, Roy E. South to the Naktong, North to the Yalu (1961), Official US Army history covers the Eighth Army and X Corps from June to November 1950

- Appleman, Roy E.. East of Chosin: Entrapment and Breakout in Korea (1987); Escaping the Trap: The U.S. Army in Northeast Korea, 1950 (1987); Disaster in Korea: The Chinese Confront MacArthur (1989); Ridgway Duels for Korea (1990).

- Blair, Clay. The Forgotten War: America in Korea, 1950-1953 (1987), revisionist study that attacks senior American officials

- Field Jr., James A. History of United States Naval Operations: Korea, University Press of the Pacific, 2001, ISBN 0-89875-675-8. official U.S. Navy history

- Farrar-Hockley, General Sir Anthony. The British Part in the Korean War, HMSO, 1995, hardcover 528 pages, ISBN 0-11-630962-8

- Futrell, Robert F. The United States Air Force in Korea, 1950-1953, rev. ed. (Office of the Chief of Air Force History, 1983), official U.S. Air Force history

- Hallion, Richard P. The Naval Air War in Korea (1986).

- Hamburger, Kenneth E. Leadership in the Crucible: The Korean War Battles of Twin Tunnels and Chipyong-Ni. Texas A. & M. U. Press, 2003. 257 pp.

- Hastings, Max. The Korean War (1987). British perspective

- Hermes, Jr., Walter. Truce Tent and Fighting Front (1966), Official US Army history on the "stalemate" period from October 1951 to July 1953.

- James, D. Clayton The Years of MacArthur: Triumph and Disaster, 1945-1964 (1985)

- James, D. Clayton with Anne Sharp Wells, Refighting the Last War: Command and Crises in Korea, 1950-1953 (1993)

- Johnston, William. A War of Patrols: Canadian Army Operations in Korea. U. of British Columbia Press, 2003. 426 pp.

- Kindsvatter, Peter S. American Soldiers: Ground Combat in the World Wars, Korea, and Vietnam. U. Press of Kansas, 2003. 472 pp.

- Millett, Allan R. Their War for Korea: American, Asian, and European Combatants and Civilians, 1945-1953. Brassey's, 2003. 310 pp.

- Montross, Lynn et al., History of U.S. Marine Operations in Korea, 1950-1953, 5 vols. (Washington: Historical Branch, G-3, Headquarters, Marine Corps, 1954-72),

- Mossman, Billy. Ebb and Flow (1990), Official US Army history covers November 1950 to July 1951.

- Russ, Martin. Breakout: The Chosin Reservoir Campaign, Korea 1950, , Penguin, 2000, 464 pages, ISBN 0-14-029259-4

- Toland, John. In Mortal Combat: Korea, 1950-1953 (1991)

- Varhola, Michael J. Fire and Ice: The Korean War, 1950-1953 (2000)

- Watson, Brent Byron. Far Eastern Tour: The Canadian Infantry in Korea, 1950-1953. 2002. 256 pp.

Origins, politics, diplomacy

- Chen Jian, China's Road to the Korean War: The Making of the Sino-American Confrontation (Columbia University Press, 1994),

- Cumings, Bruce. The Origins of the Korean War, Vol. 1: Liberation and the Emergence of Separate Regimes, 1945-1947, (1981), ISBN 0-691-10113-2; The Origins of the Korean War, Vol. 2: The Roaring of the Cataract, 1947-1950, Princeton University Press, 1990, ISBN 0-691-07843-2, prewar; stress on internal Korean politics

- Goncharov, Sergei N., John W. Lewis; and Xue Litai, Uncertain Partners: Stalin, Mao, and the Korean War, Stanford University Press, 1993, ISBN 0-8047-2521-7, diplomatic

- Kaufman, Burton I. The Korean War: Challenges in Crisis, Credibility, and Command. Temple University Press, 1986), focus is on Washington

- Matray, James. "Truman's Plan for Victory: National Self Determination and the Thirty-Eighth Parallel Decision in Korea," Journal of American History 66 (September, 1979), 314-33. Online at JSTOR

- Millett, Allan R. The War for Korea, 1945–1950: A House Burning vol 1 (2005)ISBN 0-7006-1393-5, origins

- Schnabel, James F. United States Army in the Korean War: Policy and Direction: The First Year (Washington: Office of the Chief of Military History, 1972). official US Army history; full text online

- Spanier, John W. The Truman-MacArthur Controversy and the Korean War (1959).

- Stueck, William. Rethinking the Korean War: A New Diplomatic and Strategic History. Princeton U. Press, 2002. 285 pp.

- Stueck, Jr., William J. The Korean War: An International History (Princeton University Press, 1995), diplomatic

- Zhang Shu-gang, Mao's Military Romanticism: China and the Korean War, 1950-1953 (University Press of Kansas, 1995)

See also

- Korean War order of battle

- Battles of the Korean War

- Korean People's Army

- North Korean Air Force

- North Korean Navy

Notes

- ↑ BBC, On This Day 29 August 1950. Retrieved September 2, 2008.

- ↑ Veterans Affairs Canada, The Korean War. Retrieved September 2, 2008.

- ↑ Korean War.com, Brief account of the Korean War. Retrieved September 2, 2008.

- ↑ Embassy of France, French Participation in the Korean War. Retrieved October 31, 2006

- ↑ Korean War. Retrieved September 2, 2008.

- ↑ Dankwart A. Rustow, The Changing Global Order and Its Implications for Korea's Reunification, Sino-Soviet Affairs, Vol. XVII, No. 4, Winter 1994/5, The Institute for Sino-Soviet Studies, Hanyang University.

- ↑ Bruce Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, Vol. 1: Liberation and the Emergence of Separate Regimes, 1945–1947 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981)

- ↑ Bruce Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War (1981).

- ↑ Gregory Henderson, Korea: The Politics of the Vortex (Harvard University Press, 1968).

- ↑ Dean Acheson, The theme of China lost, Present at the Creation: My Years at the State Department (1969).

- ↑ Appleman, South to the Naktong, 15.

- ↑ Appleman, South to the Naktong.

- ↑ Appleman, South to the Naktong ch. 26, pp 381, 545

- ↑ James F. Schnabel. United States Army In The Korean War: Policy And Direction: The First Year (1972) ch 9-10; Korea Institute of Military History, The Korean War (1998) 1:730

- ↑ Robert J. Donovan, Tumultuous Years (1982), 285.

- ↑ Eliot A. Cohen and John Gooch, Military Misfortunes: The Anatomy of Failure in War (1990), 165-95.

- ↑ William Hopkins One Bugle, No Drums: The Marines at Chosin Reservoir (1986).

- ↑ Schnabel, 304.

- ↑ Korea Institute of Military History, The Korean War (2001) 2:512-29.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Brune, Lester and Robin Higham, (eds.). The Korean War: Handbook of the Literature and Research. Greenwood Press, 1994.

- Edwards, Paul M. Korean War Almanac. 2006.

- Foot, Rosemary. "Making Known the Unknown War: Policy Analysis of the Korean Conflict in the Last Decade." Diplomatic History 15 (Summer 1991): 411-31.

- Kaufman, Burton I. The Korean Conflict. Greenwood Press, 1999.

- Korea Institute of Military History. The Korean War. U of Nebraska Press, 1998. ISBN 0-8032-7802-0.

- Leitich, Keith. Shapers of the Great Debate on the Korean War: A Biographical Dictionary. 2006.

- Matray, James I. (ed.). Historical Dictionary of the Korean War. Greenwood Press, 1991.

- Millett, Allan R. “A Reader's Guide To The Korean War.” Journal of Military History 61(3): 583.

- Millett, Allan R. "The Korean War: A 50 Year Critical Historiography." Journal of Strategic Studies 24: 188-224.

- Summers, Harry G. Korean War Almanac. 1990.

- Sandler, Stanley (ed.). The Korean War: An Encyclopedia. Garland, 1995.

External links

All links retrieved September 2, 2008.

- The Center for the Study of the Korean War

- Pres. Truman Library documents on his Wake Island meeting with Gen. MacArthur

- Calvin College on the Impact of the War on the Korean People

- Facts and texts on the War

- BBC: American Military Conduct in the Korean War

- Atrocities against Americans in the Korean War

- Atrocities by Americans in the Korean War

- Quicktime sequence of 27 maps adapted from the West Point Atlas of American Wars showing the dynamics of the front.

- A Korean War Stat Lingers Long After It Was Corrected

- Animation for operations in 1950

- Animation for operations in 1951

- POW films, brainwashing and the Korean War

- Maps of the Korean War from the US Military Academy West Point

- CBC Digital Archives - Forgotten Heroes: Canada and the Korean War

- Korean War Commemoration

- FAQ from a Chinese perspective

- Chinese 50th Anniversary Korean War Memorial

- www.roll-of-honour.com - Searchable database of British Casualties during the Korean War 1951-1953

- http://www.acepilots.com/russian/rus_aces.html

- [US Casualties in Korea by State]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.