The Church Fathers or Fathers of the Church are the early and influential theologians and writers in the Christian Church, particularly those of the first five centuries. The term is used for the intellectual leaders of the Church, not necessarily saints, and does not include the New Testament authors. It also excludes writers condemned as heretics, although several of the Church Fathers, such as Tertullian and Origen, did occasionally express heterodox views.

Catholic and Orthodox traditions regarding the Fathers of the Church differ, with greater honor paid in the West to such men as Pope Gregory the Great and St. Augustine, and more attention given in the East to such writers as Basil the Great and John Chrysostom. In addition, Orthodox tradition considers the age of the Church Fathers to be open-ended, continuing up to the present day, while Catholic tradition ends the age much earlier.

Protestant thought emphasizes the principle of "scripture only" as a basis for Christian doctrine, but in fact relied heavenly on the tradition of the Church Fathers in the early stages of the Reformation. Later Protestant thought has challenged this by seeking to make a distinction between the tradition of the Church Fathers and the teachings of earliest Christian communities led by Jesus and the Apostles. Some have pointed out that the heart of the problem of the tradition of the Church Fathers is its authoritarian doctrine of hierarchical church. Even so, one can find that the Church Fathers created a monument to God-centered thinking during the first several centuries, and that their thought is often truly inspiring and worthy of serious study.

Apostolic Fathers

The earliest Church Fathers, those of the first two generations after the [[Apostle|Apostles of Christ, are usually called the Apostolic Fathers. Famous Apostolic Fathers include Clement of Rome (c. 30-100), Ignatius of Antioch, and Polycarp of Smyrna.

Clement of Rome

The epistle known as 1 Clement (c. 96) is attributed to this early bishop of Rome. It was widely read in the churches and is considered the earliest Christian epistle outside the New Testament. Tradition identifies Clement as the fourth pope.

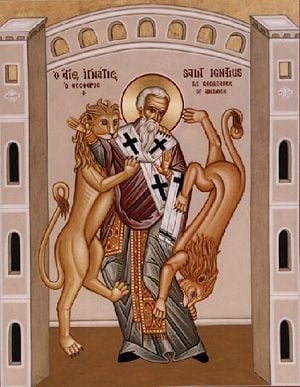

Ignatius of Antioch

Ignatius of Antioch (c. 35-110) was the third bishop of Antioch and a student of the Apostle John. En route to his martyrdom in Rome, Ignatius wrote a series of letters to various churches, and these have been preserved as an example of the theology of the earliest Christians. Important topics addressed in these letters include ecclesiology, the sacraments, and the central role of bishops in authorized orthodox teaching.

Polycarp

Polycarp (c. 69-c. 156) was the bishop of Smyrna (now İzmir in Turkey). In 155, the Smyrnans demanded Polycarp's execution as a Christian, and he died a martyr. He was also an important figure in the controversy over the date on which Christians celebrate Easter.

Didache

Purporting to be the work of more than one author, the Didache, meaning "Teaching," is a brief early Christian treatise, traditionally ascribed to the Twelve Apostles. However, it is dated by most scholars to the early second century.[1] It gives instructions to Christian communities and contains passages considered to be the first written catechism, as well as sections dealing with rituals such as baptism, eucharist, and church organization.

Hermas

The Shepherd of Hermas was a popular second-century work considered scripture by some of the Church Fathers, such as Irenaeus and Tertullian. It was written at Rome by the presbyter Hermas, sometimes identified as a brother of Pope Pius I. The work comprises a number of apocalyptic visions, mandates, and parables, calling the church to repent of its sins and prepare for the imminent coming of Christ.

Other Apostolic Fathers

Several other writings are also included among the Apostolic Fathers: For example the anti-Jewish letter known as the Epistle of Barnabas, which was often appended to the New Testament; and fragments of the works of Papias. The Epistle of Mathetes and the discourse of Quadratus of Athens—usually included in collections of the Apostolic Fathers—are normally counted among the apologists rather than the Church Fathers.

Greek Fathers

Those who wrote in Greek are called the Greek (Church) Fathers. Famous Greek Fathers include Irenaeus of Lyons, Clement of Alexandria, Origen, Athanasius of Alexandria, John Chrysostom, and the Three Cappadocian Fathers. Others, however, are also studied.

Clement of Alexandria

Clement of Alexandria (c. 150-211/216), was a distinguished teacher in the city which became one of early Christianity's most important intellectual centers. He united Greek philosophical traditions with Christian doctrine and thus developed what later became known as Christian Platonism.

Origen

Origen (c. 185 - c. 254) also taught in Alexandria, reviving the catechetical school where Clement had taught. He interpreted scripture allegorically and further developed the tradition of Christian Platonism. Origen taught a doctrine of universal salvation in which even demons would eventually be reunited with God. Although some of his views were declared anathema in the sixth century by the Fifth Ecumenical Council,[2] Origen's thought exercised significant influence.

Irenaeus of Lyons

Irenaeus, (d. near the end of the third century) was bishop of Lugdunum in Gaul, which is now Lyons, France. A disciple of Polycarp, his best-known book, Against Heresies (c. 180), enumerated heresies and attacked them. Irenaeus wrote that the only way for [Christian]s to retain unity was to humbly accept one doctrinal authority of orthodox bishops, with disputes resolved by episcopal councils. His work is a major source for understanding the heterodox movements of the second century and the orthodox churches' attitude in combating them.

Athanasius of Alexandria

Athanasius (c. 293-May 2, 373), also known as St. Athanasius the Great, was a theologian who later became the patriarch ("pope") of Alexandria, a leader of immense significance in the theological battles of the fourth century. He is best remembered for his role in the conflict with Arianism, although his influence covers a vast array of theological topics.

Cappadocian Fathers

The Cappadocians were three physical brothers who were instrumental in the promotion of Christian theology and are highly respected in both Western and Eastern churches as saints: Basil the Great, Gregory of Nyssa, and Peter of Sebaste. These scholars, along with their close friend, Gregory of Nazianzus, proved that Christians could hold their own in conversations with learned Greek-speaking intellectuals. They made major contributions to the definition of the Trinity, culminating at the First Council of Constantinople in 381, where the final version of the Nicene Creed was formulated.

John Chrysostom

John Chrysostom (c. 347-c. 407), archbishop of Constantinople, is known for his eloquence in preaching and public speaking, his denunciation of the abuse of authority by both ecclesiastical and political leaders, the Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom, his ascetic sensibilities, his violent opposition to paganism, and his sermons denouncing Judaism. He is particularly honored in the Eastern Orthodox Church.

Latin Fathers

Those fathers who wrote in Latin are called the Latin (Church) Fathers. Famous Latin Fathers include Tertullian, Cyprian of Carthage, Gregory the Great, Augustine of Hippo, Ambrose of Milan, and Jerome.

Tertullian

Quintus Septimius Florens Tertullianus (c. 160-c. 225) was a prolific writer of apologetic, theological, anti-heretical, and ascetic works. He is believed to have introduced the Latin term "trinitas" (Trinity) to the Christian vocabulary and also the formula "three persons, one substance"—tres personae, una substantia. Later in life, Tertullian joined the Montanists, a heretical sect, but his writings by and large are considered as a shining example of orthodoxy.

Cyprian

Cyprian (died September 14, 258) was bishop of Carthage and an important early Christian writer who eventually died a martyr at Carthage. He is particularly important in defining the Christian church as "Catholic," meaning "universal," and his insistence that there can be no salvation outside of the Christian church.

Ambrose

Ambrose (c. 338-April 4, 397) was the bishop of Milan who became one of the most influential ecclesiastical figures of the fourth century. He promoted the rights of the church in relation to the imperial state and is counted as one of the four original Doctors of the Church. He was also the teacher of Saint Augustine.

Jerome

Jerome (c. 347-September 30, 420) is best known as the translator of the Bible from Greek and Hebrew into Latin. He was also a noted Christian apologist and a source of many historical facts concerning Christian history. Jerome's edition of the Bible, the Vulgate, is still an important text of the Roman Catholic Church.

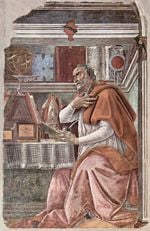

Augustine

Augustine (November 13, 354-August 28, 430), the bishop of Hippo, was both a philosopher and theologian, as well as an influential church leader in north Africa. He framed the concept of original sin and related teachings on divine grace, free will, and predestination, as well as the theory of the just war. His works remain among the most influential in Christian history.

Gregory the Great

Pope Gregory I (c. 540-March 12, 604) reigned as bishop of Rome from September 3, 590, until his death. He was the first of the popes from a monastic background and did much to solidify the leadership of the Roman church. Although he was active relatively late, he is considered one of the four great Latin Fathers along with Ambrose, Augustine, and Jerome.

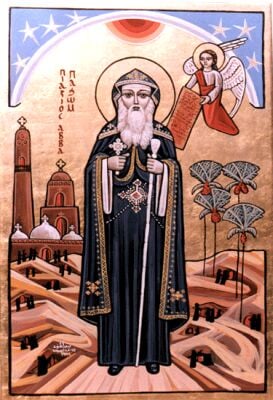

Other Fathers

The Desert Fathers were early monastics living in the Egyptian desert; although they did not write as much, their influence was also great. Among them are Anthony the Great and Pachomius. A great number of their usually short sayings are collected in the Apophthegmata Patrum ("Sayings of the Desert Fathers").

The Christian apologists are sometimes designated as the Apologetic Fathers. They wrote to justify and defend Christian doctrine against its critics rather than as Christians speaking to other Christians. Among the best known of these are Justin Martyr, Tatian, Athenagoras of Athens, and Hermias.

A small number of Church Fathers wrote in other languages: Saint Ephrem, for example, wrote in Syriac, although his works were widely translated into Latin and Greek.

Later Church Fathers

Although there is no definite rule on the subject, the study of the "early" Church normally ends at the Council of Chalcedon in 451. However a number of later writers are also often included among the "The Fathers." Among these, Gregory the Great (d. 604) in the West and John of Damascus (d. about 754) in the East. Western tradition also sometimes counts Isidore of Seville (d. 636) and the Venerable Bede (d. 735) among the Fathers.

The Eastern Orthodox Church does not consider the age of Church Fathers to be over and includes later influential writers, even up to the present day. The study of the Church Fathers in the East therefore is a significantly broader one than in the West.

The Church Fathers and Protestantism

Although much Protestant religious thought is based on the principle of Sola Scriptura (scripture only), the early Protestant reformers relied heavily on the theological views set forth by the early Church Fathers. The original Lutheran Augsburg Confession of 1531, for example, begins with the mention of the doctrine professed by the Fathers of the First Council of Nicea. John Calvin's French Confession of Faith of 1559 states, "And we confess that which has been established by the ancient councils, and we detest all sects and heresies which were rejected by the holy doctors, such as St. Hilary, St. Athanasius, St. Ambrose and St. Cyril."[3] The Scots Confession of 1560 deals with general councils in its twentieth chapter.

Likewise, the Thirty-nine Articles of the Church of England, both the original of 1562-1571 and the American version of 1801, explicitly accept the Nicene Creed in article 7. Even when a particular Protestant confessional formula does not mention the Nicene Council or its creed, this doctrine is nearly always asserted.

Only in the nineteenth century did Protestant theologians begin seriously challenging the ideas of the early Church Fathers by using the historical-critical method of biblical analysis to attempt to separate the teachings of Jesus himself from those of the later church tradition. Writers such as Albrecht Ritschl and Adolf Harnack were among the influential pioneers of this movement.

Patristics

The study of the Church Fathers is known as "Patristics." Works of the Church Fathers in early Christianity prior to Nicene Christianity were translated into English in a nineteenth century collection known as Ante-Nicene Fathers.[4] Those of the period of the First Council of Nicea (325 C.E.) and continuing through the Second Council of Nicea (787) are collected in Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers.[5] Patristics is a major topic of study in Eastern Orthodox tradition, as it includes not only the ancient Fathers, but also more recent developments in Orthodox theology and church history up until the present day.

Assessment

The writings of the Church Fathers represent some of the most significant intellectual work ever created. They also provide important records concerning the history of early Christianity and its development in the Roman Empire. The teachings of the Church Fathers have deeply impacted the lives of billions of people throughout the world.

At the same time, while many of the Church Fathers' writings make fascinating and inspirational reading, they also portray bitter disagreements with many believers who have held views deemed to be unorthodox, leading to excommunications enacted against them. These divisions within Christianity and the suppression of heterodoxy at the instigation of many of the Church Fathers are considered by critics as a sad feature of Christian history. According to recent "house church" advocates such as Beresford Job, this problem resulted from the authoritarian doctrine of hierarchical church developed by the Church Fathers contrary to the spirit of the New Testament.[6]

It is true that the importance of love in the church was much stressed by Church Fathers such as Augustine, but it seems that they were also very busy in trying to come up with dogmatically and ecclesiastically definitive points in the doctrine of the Trinity, Christology, and other theological subjects. Some of the Church Fathers were also strongly antisemitic, leading the church to treat the Jews badly. This may be the reason why modern Protestantism has developed a trend to look beyond the tradition of the Church Fathers to uncover the authentic teachings, if any, of Jesus and the New Testament. Nevertheless, it is interesting that the list of the Church Fathers includes Origen and Tertullian, who occasionally expressed heterodox views. So, the theological tradition of the Church Fathers is perhaps not as rigid and inflexible as one thinks.

Given all this, one can still find that the Church Fathers created a monument to God-centered thinking during the first several centuries. Their thought is often truly inspiring and worthy of serious study.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Bruce M. Metzger, The Canon of the New Testament (Oxford University Press, 1997).

- ↑ In Church Fathers: The Anathematisms of the Emperor Justinian Against Origen (Schaff, op. cit.). Retrieved June 30, 2008.

- ↑ Henry Beveridge (trans.), Calvin's Tracts (Edingburgh, Calvin Translation Socieity, 1849).

- ↑ Alexander Roberts et al, eds., Ante-Nicene Fathers: The Writings of the Fathers Down to A.D. 325. 10 vols. Hendrickson Publishers, 1994.

- ↑ Alexander Roberts et al (eds.), Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers: First Series (Hendrickson Publishers, 1994).

- ↑ Beresford Job, "The Traditions of the Church Fathers—The Heart of the Problem." Retrieved February 21, 2009.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Calvin, John, and Henry Beveridge (trans.). Calvin's Tracts. Calvin Translation Society. 1849. ISBN 9781579108.

- Campenhausen, Hans. The Fathers of the Church. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 1998. ISBN 9781565630956.

- Colish, Marcia L. The Fathers and Beyond: Church Fathers between Ancient and Medieval Thought. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2008. ISBN 9780754659440.

- Di Berardino, Angelo, and Adrian Walford (trans.). Patrology: The Eastern Fathers from the Council of Chalcedon (451) to John of Damascus (750). Cambridge: J. Clarke, 2006. ISBN 9780227679791.

- Drobner, Hubertus R., and William Harmless (contributors), Siegfried S. Schatzmann (trans.). The Fathers of the Church: A Comprehensive Introduction. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 2007. ISBN 9781565633315.

- Harvey, Susan Ashbrook, and David G. Hunter. The Oxford Handbook of Early Christian Studies. Oxford handbooks in religion and theology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008. ISBN 9780199271566.

- Metzger, Bruce M. The Canon of the New Testament. Oxford University Press, 1997. ISBN 9780198269540.

- Pelikan, Jaroslav. The Excellent Empire: The Fall of Rome and the Triumph of the Church. The Rauschenbusch lectures, new ser., 1. San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1987. ISBN 9780062546364.

- Rankin, David. From Clement to Origen: The Social and Historical Context of the Church Fathers. Aldershot, England: Ashgate Pub, 2006. ISBN 9780754657163.

- Roberts, Alexander, et al (eds.). Ante-Nicene Fathers: The Writings of the Fathers Down to A.D. 325. 10 vols. Hendrickson Publishers, 1994. ISBN 1565630823.

- —. Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers: First Series. 14 vols. Hendrickson Publishers, 1994. ISBN 1565630947.

- —. Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers: Second Series. 14 vols. Hendrickson Publishers, 1994. ISBN 1565631161.

External links

All links retrieved December 10, 2023.

- Church Fathers' works in English edited by Philip Schaff. www.ccel.org

- Church Fathers at Newadvent.org www.newadvent.org

- Church Fathers at the Patristics In English Project Site www.seanmultimedia.com

- Early Church Fathers Additional Texts Part of the Tertullian corpus. www.tertullian.org

- Primer on the Church Fathers at Corunum www.cin.org

- The Fathers of the Church: A New Translation, by Ludwig Schopp. www.orthodox.cn

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.