Dinosaur Provincial Park

| Dinosaur Provincial Park | |

|---|---|

| IUCN Category III (Natural Monument) | |

| | |

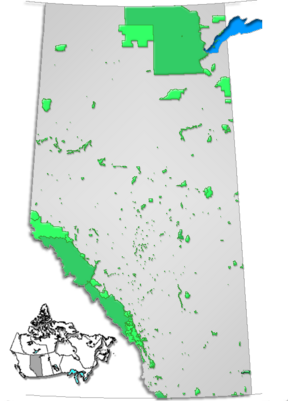

| Location: | Alberta, Canada |

| Nearest city: | Brooks |

| Area: | 73.29km² |

| Established: | 1955 |

| Governing body: | Alberta Tourism, Parks and Recreation |

Dinosaur Provincial Park is located in the valley of the Red Deer River in southeastern Alberta, Canada. The area is noted for its striking badlands topography. The nearly 29 square miles (75 km²) park is well known for being one of the largest known dinosaur fossil beds in the world. Thirty-nine distinct dinosaur species have been discovered at the park, and more than 500 specimens have been removed and exhibited in museums around the world. Additional fossilized remains include those of cretaceous fish, reptiles, and amphibians.

The park is well known for its beautiful scenery and diverse plant and animal life. Its habitat is considered part of an endangered riverine ecosystem. Its paleontological significance justified it becoming a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1979.

Geography

Dinosaur Provincial Park boasts a very complex ecosystem including three communities: prairie grasslands, badlands, and riverside.

The park is located in the Dry Mixed-grass sub-region of the Grassland Natural Region. This is the warmest and driest sub-region in Alberta. Permanent streams are relatively rare, though those that do exist are deeply carved into the bedrock in some places, exposing Cretaceous shales and sandstones and thereby creating extensive badlands.[1]

The Grassland Natural Region is characterized by cold winters, warm summers, high winds, and low precipitation. The region is a flat to gently rolling plain with a few major hill systems, punctuated by exposed bedrock, carved sandstone cliffs, and boulders.

Some 75 million years ago, however, the landscape was very different. The climate was subtropical, with lush forests covering a coastal plain. Rivers flowed east, across the plain into a warm inland sea. The low swampy country was home to a variety of animals, including dinosaurs. The conditions were also perfect for the preservation of their bones as fossils. The rivers that flowed here left sand and mud deposits that make up the valley walls, hills, and hoodoos of modern-day Dinosaur Provincial Park.

At the end of the last ice age (about 13,000 years ago) water from melting ice carved the valley through which the Red Deer River now flows. Today, water from prairie creeks and runoff continues to sculpt the layers of these badlands, the largest in Canada.

Flora and fauna

The three distinct habitats of Dinosaur Provincial Park each support many animals and plants. Cottonwood and willow trees share the riverbanks with bushes. Cacti, greasewood, and many species of sagebrush survive in the badlands. Some of the most northern species of cactus, including Opuntia (prickly pear) and Pediocactus (pincushion), can be observed in full bloom during the latter half of June. Prairie grasses dominate above the valley rim. Curlews and Canada geese are among the 165 bird species that can be seen in the spring and summer. In May and June, warblers, woodpeckers, and waterfowl are easy to observe in the cottonwood groves. Away from the river's edge look for golden eagles, prairie falcons, and mountain bluebirds.

Choruses of coyotes are common at dusk, as are the calls of nighthawks. Cottontail rabbits, white-tail and mule deer, and pronghorn can all be seen in the park. The prairie rattlesnake, bull snake, and red-sided garter snake are present, as well as black widow spiders and scorpions.

Geology

A badlands is a type of arid terrain where softer sedimentary rocks and clay-rich soils have been extensively eroded by wind and water. It can resemble malpaÃs, a terrain of volcanic rocks. Canyons, ravines, gullies, hoodoos, and other such geological forms are common in badlands. Badlands often have a spectacular color display that alternates from dark black/blue coal stria to bright clays to red scoria (a type of volcanic rock).

The term badlands is apt as they contain steep slopes, loose dry soil, slick clay, and deep sand, all of which impede travel and other uses. Badlands that form in arid regions with infrequent but intense rain, sparse vegetation, and soft sediments create a recipe for massive erosion.

Some of the most famous fossil beds are found in badlands, where erosion rapidly exposes the sedimentary layers and the scant cover of vegetation makes surveying and fossil hunting relatively easy.

The sediments of Dinosaur Provincial Park span 2.8 million years and three formations: The terrestrial Oldman Formation at the base of the strata, the terrestrial Dinosaur Park Formation above, and the marine Bearpaw at the top. The Dinosaur Park Formation, which contains most of the fossils from articulated skeletons, was primarily laid down by large meandering rivers in very warm temperate coastal lowlands along the western margin of the Western Interior Seaway. The formation dates to the Late Campanian, about 75 million years ago. The Dinosaur Park Formation spans about 1 million years.

A hoodoo is a tall thin spire of rock that protrudes from the bottom of an arid drainage basin or badland. Hoodoos are composed of soft sedimentary rock and are topped by a piece of harder, less easily eroded stone that protects the column from the elements. Hoodoos range in size from that of an average human to heights exceeding a 10-story building. Hoodoo shapes are affected by the erosional patterns of alternating hard and softer rock layers. Minerals deposited within different rock types cause hoodoos to have different colors throughout their height.

Paleontology

| Dinosaur Provincial Park* | |

|---|---|

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| State Party | |

| Type | Natural |

| Criteria | vii, viii |

| Reference | 71 |

| Region** | Europe and North America |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 1979Â (3th Session) |

| * Name as inscribed on World Heritage List. ** Region as classified by UNESCO. | |

Dinosaur Provincial Park preserves an extraordinarily diverse group of freshwater vertebrates. Fish include sharks, rays (such as the durophage Myledaphus), paddlefish, bowfins, gars, and teleosts. Amphibians include frogs, salamanders, and the extinct albanerpetontids. Reptiles include lizards (such as the large monitor Paleosaniwa), a wide range of turtles, crocodilians, and the fish-eating Champsosaurus. Mammals such as shrews, marsupials, and squirrel-like rodents are also represented, although usually only by their fossilized teeth, rather than bones.[2]

Mega-plant fossils are rare in the park, but pollen grains and spores collected suggest that these Campanian forests contained sycamore, magnolia, and bald cypress trees, along with Metasequoia.

The dinosaur remains of the park are astonishingly diverse. They include:

Ceratopsia

- Leptoceratops sp.

- Centrosaurus apertus,'C. brinkmani

- Styracosaurus albertensis

- Pachyrhinosaurus

- Chasmosaurus belli, C. russeli, C. irvinensis

Hadrosauridae

- Corythosaurus casuarius

- Gryposaurus notabilis, G. incurvimanus

- Lambeosaurus lambei, L. magnicristatus

- Prosaurolophus

- Parasaurolophus walkeri

Ankylosauria

- Panoplosaurus

- Edmontonia

- Euoplocephalus

Hypsilophodontidae

- Orodromeus

Pachycephalosauria

- Stegoceras

Tyrannosauridae

- Daspletosaurus sp.

- Gorgosaurus libratus

Ornithomimidae

- Ornithomimus

- Struthiomimus

- New ornithomimid species A

- Chirostenotes pergracilis

- Chirostenotes elegans

- Chirostenotes collinsi

Dromaeosauridae

- Dromaeosaurus

- Saurornitholestes

- ?new dromaeosaur species A

- ?new dromaeosaur species B

Troodontidae

- Troodon

- new troodontid species A

Classification Uncertain

- Ricardoestesia gilmorei

Birds such as Hesperornithiformes were present, as well as giant Pterosauria related to Quetzalcoatlus. Stagodont marsupials, placentals, and multituberculates scurried underfoot.

History

In 1884, Joseph Tyrell, a Canadian geologist, cartographer, and mining consultant, was assisting a surveyor sent to the area. During this trip he found bones later identified as an Albertosaurus. Four years later, the Geological Survey of Canada sent Thomas Weston as its fossil collector. Most of his discoveries were in the area known as Dead Lodge Canyon, now part of the park. Another collector, Lawrence Lamb, was sent in 1897. As word spread, other collectors arrived.

The Park was established as "Steveville Dinosaur Provincial Park" on June 27, 1955, as part of Alberta's 50th Jubilee Year. The goal of the park's creation was to protect the fossil bone beds. The park's first warden was Roy Fowler, a farmer and amateur fossil hunter. In 1962, the park's name was changed to the simpler "Dinosaur Provincial Park."

The park was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site on October 26, 1979, for its nationally significant badlands landscape, riverside habitats, and for the international importance of the fossils found here.

Until 1985 discoveries made in the park had to be shipped to museums throughout the world for scientific analysis and display, including the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, the Canadian Museum of Nature in Ottawa, and the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. This changed with the opening of the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology 62Â miles (100Â km) upstream in Midland Provincial Park near Drumheller.

Looking ahead

The Blackfoot Confederacy made the Alberta badlands their home for many centuries. The majestic topography and the diversity of plant and animal life no doubt played a part in their religious beliefs and practices. The dinosaur bones they found were referred to as the "Grandfather of the Buffalo".[3]

Since the early part of the twentieth century this region has been a playground of sorts for North American paleontologists. The number and quality of specimens is recognized as among the best in the world. The American Museum of Natural History displays more original dinosaur skeletons from Alberta than from any other area of the world.[3]

The park was founded in 1952 as a means of protecting the important historical finds. Approximately 70 percent of the park is a Natural Preserve, which has restricted access for resource protection and public safety reasons. Entry is only via guided programs.

Dinosaur Provincial Park will continue to be a haven for scientists for many years as they seek to broaden their understanding of the Earth's history and evolution.

Notes

- â Government of Alberta, Dinosaur Provincial Park Nature. Retrieved February 13, 2009.

- â World Heritage Site, Dinosaur Provincial Park. Retrieved February 16, 2009.

- â 3.0 3.1 Currie and Koppelhus (2005).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Braman, D. R. The Palaeontology and Geology of the Dinosaur Provincial Park Area, Alberta. Drumheller, Alberta: Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology, 2005. OCLC 63110092

- Currie, Philip J., and Eva B. Koppelhus. Dinosaur Provincial Park: A Spectacular Ancient Ecosystem Revealed. Life of the past. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2005. ISBN 978-0253345950

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Dinosaur Provincial Park. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

External links

All links retrieved January 29, 2024.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.