Flamenco

Flamenco is a Spanish musical genre. Flamenco embodies a complex musical and cultural tradition. Although considered part of the culture of Spain in general, flamenco actually originates from one region—Andalusia. However, other areas, mainly Extremadura and Murcia, have contributed to the development of several flamenco musical forms, and a great number of renowned flamenco artists have been born in other territories of the state. The roots of flamenco are not precisely known, but it is generally acknowledged that flamenco grew out of the unique interplay of native Andalusian, Islamic, Sephardic, and Gypsy cultures that existed in Andalusia prior to and after the Reconquest. Latin American and especially Cuban influences have also been important to shape several flamenco musical forms.

Once the seeds of flamenco were planted in Andalusia, it grew as a separate subculture, first centered in the provinces of Seville, Cádiz and part of Málaga—the area known as Baja Andalucía (Lower Andalusia)—but soon spreading to the rest of Andalusia, incorporating and transforming local folk music forms. As the popularity of flamenco extended to other areas, other local Spanish musical traditions (i.e. the Castilian traditional music) would also influence, and be influenced by, the traditional flamenco styles.

Overview

Many of the details of the development of flamenco are lost in Spanish history. There are several reasons for this lack of historical evidence:

- Flamenco sprang from the lower levels of Andalusian society, and thus lacked the prestige of art forms among the middle and higher classes. Flamenco music also slipped in and out of fashion several times during its existence. Many of the songs in flamenco still reflect the spirit of desperation, struggle, hope, and pride of the people during this time of persecution.

- The turbulent times of the people involved in flamenco culture. The Moors, the Gitanos and the Jews were all persecuted and expelled by the Spanish Inquisition in 1492.

- The Gitanos have been fundamental in maintaining this art form, but they have an oral culture. Their folk songs were passed on to new generations by repeated performances in their social community. The non-gypsy Andalusian poorer classes, in general, were also illiterate.

- Lack of interest by historians and musicologists. "Flamencologists" have usually been flamenco connoisseurs of diverse professions (a high number of them, like Félix Grande, Caballero Bonald or Ricardo Molina, have been poets), with no specific academic training in the fields of history or musicology. They have tended to rely on a limited number of sources (mainly the writings of 19th century folklorist Demófilo, notes by foreign travellers like George Borrow, a few accounts by writers and the oral tradition), and they have often ignored other data. Nationalistic or ethnic bias has also been frequent in flamencology. This started to change in the 1980s, when flamenco slowly started to be included in music conservatories, and a growing number of musicologists and historians began to carry out more rigorous research. Since then, some new data have shed new light on it. (Ríos Ruiz, 1997:14)

There are questions not only about the origins of the music and dances of flamenco, but also about the origins of the very word flamenco. Whatever the origins of the word, in the early nineteenth century it began to be used to describe a way of life centered around this music and usually involving Gypsies (in his 1842 book "Zincali," George Borrow writes that the word flemenc [sic] is synonymous with "Gypsy").

Blas Infante, in his book Orígenes de lo flamenco y secreto del cante jondo, controversially argued that the word flamenco comes from Hispano-Arabic word fellahmengu, which would mean "expelled peasant" [1] Yet there is a problem with this theory, in that the word is first attested three centuries after the end of the Moorish reign. Infante links the term to the ethnic Andalusians of Muslim faith, the Moriscos, who would have mixed with the Gypsy newcomers in order to avoid religious persecution. Other hypotheses concerning the term's etymology include connections with Flanders (flamenco also means Flemish in Spanish), believed by Spanish people to be the origin of the Gypsies, or the flameante (arduous) execution by the performers, or the flamingos. [2]

Background

For a complete picture of the possible influences that gave rise to flamenco, attention must be paid to the cultural and musical background of the Iberian Peninsula since Ancient times. Long before the Moorish invasion in 711, Visigothic Spain had adopted its own liturgic musical forms, the Visigothic or Mozarabic rite, strongly influenced by Byzantium. The Mozarabic rite survived the Gregorian reform and the Moorish invasion, and remained alive at least until the tenth or eleventh century. Some theories, started by Spanish classical musician Manuel de Falla, link the melismatic forms and the presence of Greek Dorian mode (in modern times called “Phrygian mode”) in flamenco to the long existence of this separate Catholic rite. Unfortunately, owing to the type of musical notation in which these Mozarabic chants were written, it is not possible to determine what this music really sounded like, so the theory remains unproven.

Moor is not the same as Moslem. Moor comes from the Latin Mauroi, meaning an inhabitant of North Africa. Iberians came from North Africa, and so did the Carthaginians. Moorish presence in the peninsula goes back thousands of years. The appearance of the Moslems in 711 helped to shape particular music forms in Spain. They called the Iberian Peninsula “Al-Andalus,” from which the name of Andalusia derives. The Moorish and Arab conquerors brought their musical forms to the Peninsula, and at the same time, probably gathered some native influence in their music. The Emirate, and later Caliphate of Córdoba became a center of influence in both the Muslim and Christian worlds and it attracted musicians from all Islamic countries. One of those musicians was Zyriab, who imported forms of the Persian music, revolutionized the shape and playing techniques of the Lute (which centuries later evolved into the vihuela and the guitar), adding a fifth string to it, and set the foundations for the Andalusian nuba, the style of music in suite form still performed in North African countries.

The presence of the Moors was also decisive in shaping the cultural diversity of Spain. Owing to the extraordinary length of the Reconquest started in the North as early as 722 and completed in 1492 with the conquest of Granada, the degree of Moorish influence on culture, customs and even language varies enormously between the North and the South. Music cannot have been alien to that process. While music in the North of the Peninsula has a clear Celtic influence which dates to pre-Roman times, Southern music is certainly reminiscent of Eastern influences. To what extent this Eastern flavor is owed to the Moors, the Jews, the Mozarabic rite (with its Byzantine influence), or the Gypsies has not been clearly determined.

During the Reconquest, another important cultural influence was present in Al-Andalus: the Jews. Enjoying a relative religious and ethnic tolerance in comparison to Christian countries, they formed an important ethnic group, with their own traditions, rites, and music, and probably reinforced the middle-Eastern element in the culture and music forms of Al-Andalus. Certain flamenco palos like the Peteneras have been attributed a direct Jewish origin (Rossy 1966).

Andalusia after the Reconquest

The fifteenth century marked a small revolution in the culture and society of Southern Spain. The following landmarks each had future implications on the development of flamenco: first, the arrival of nomad Gypsies in the Iberian Peninsula in 1425 (Grande, 2001); then the conquest of Granada, the discovery of America and the expulsion of the Jews, all of them in 1492.

In the thirteenth century, the Christian Crown of Castile had already conquered most of Andalusia. Although Castilian kings favored a policy of repopulation of the newly conquered lands with Christians, part of the Muslim population remained in the areas as a religious and ethnic minority, called “mudéjares.”

Granada, the last Muslim stronghold in the Iberian Peninsula, fell in 1492 when the armies of the Catholic Monarchs Ferdinand II of Aragon and queen Isabella of Castile invaded this city after about 800 years of Moslem rule. The Treaty of Granada guaranteed religious tolerance, and this paved the way for the Moors to surrender peacefully. Months after, the Spanish Inquisition used its influence to convince Ferdinand and Isabella, who were political allies of the Church of Rome, to break the treaty and force the Jews to either convert to Christianity or leave Spain. The Alhambra decree of March 31, 1492 ordered the expulsion of all non-converted Jews from Spain and its territories and possessions by July 31, 1492, on charges that they were trying to convert the Christian population to Judaism. Some chose to adopt the Catholic religion (Conversos), but they often kept their Judaic beliefs privately. For this reason, they were closely watched by the Spanish Inquisition, and accusations of being false converts often lead them to suffer torture and death.

In 1499, about 50,000 Moriscos were coerced into taking part in mass baptism. During the uprising that followed, people who refused the choices of baptism or deportation to Africa were systematically eliminated. What followed was a mass exodus of Moslems, Sephardi Jews and Gitanos from Granada city and the villages into the surrounding Sierra Nevada mountain region (and its hills) and the rural country. Many Moslems, now known as Moriscos, officially converted to Christianity, but kept practicing their religion in private and also preserved their language, dress and customs. The Moriscos rose up on several occasions during the sixteenth century, and were finally expelled from Spain at the beginning of the seventeenth century.

The conquest of Andalusia implied a strong penetration of Castilian culture in Andalusia, which surely influenced the music and folklore. The expulsion of the Sephardi Jews and Moriscos could have led to a weakening of middle-Eastern influence on Andalusian culture. However, during the fifteenth century groups of Gypsies, known as Gitanos in Spain, entered the Iberian Peninsula. At the beginning, they were well-tolerated. The Spanish nobles enjoyed their dances and music, and they were regularly employed to entertain guests at private parties. The Gypsies, therefore, were in touch (at least geographically) with the Morisco population until the expulsion of the latter in the sixteenth century. According to some theories, suggested by authors like George Borrow and Blas Infante and supported by other flamenco historians like Mairena and Molina, many Moriscos even joined the Gypsy nomad tribes and eventually became undistinguishable from them. This has not been proved scientifically. It is though generally accepted that the Zambra of the Gypsies of Granada, still performed nowadays, is derived from the original Moorish Zambra.

The clash between Gypsy and the Spanish would be manifest by the end of the century. For centuries, the Spanish monarchy tried to force the Gypsies to abandon their language, customs and music. During the Reconquista, tolerance towards Gypsies ended as they were put into ghettos. This isolation helped them retain the purity of their music and dance. In 1782, the Leniency Edict of Charles III restored some freedoms to the Spanish Gypsies. Their music and dance was reintroduced and adopted by the general population of Spain. This resulted in a period of great exploration and evolution within the art form. Nomadic Gypsies became social outcasts and were in many cases the victims of persecution. This is reflected in many lyrics of "palos" like seguiriyas, in which references to hunger, prison and discrimination abound.

Influence of the New World

Recent research has revealed a major influence of Sub-Saharan African music on flamenco's prehistory. This developed from the music and dance of African slaves held by the Spanish in the New World. There are sixteenth and seventeenth century manuscripts of classical compositions that are possibly based on African folk forms, such as "negrillas," "zarambeques," and "chaconas." There are references to the fandango indiano (Indiano meaning from the Americas, but not necessarily Native American). Some critics support the idea that the names of flamenco palos like the tangos or even the fandango are derived from Bantoid languages [3], and most theories state that the rhythm of the tangos was imported from Cuba.

It is likely that in the New World, the fandango picked up dance steps deemed too inappropriate for European tastes. Thus, the dance for fandango, for chacon, and for zarabanda, were all banned in Europe at one time or another. References to Gypsy dancers can be found in the lyrics of some of these forms, e.g., the chacon. Indeed, Gypsy dancers are often mentioned in Spanish literary and musical works from the 1500s on. However, the zarabandas and jácaras are the oldest written musical forms in Spain to use the 12-beat metre as a combination of terciary and binary rhythms. The basic rhythm of the zarabanda and the jácara is 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12. The soleá and the Seguiriya, are variations on this: they just start the metre in a different beat.

The eighteenth century

During this period of development, the “flamenco fiesta” developed. More than just a party where flamenco is performed, the fiesta, either unpaid (reunion) or paid, sometimes lasting for days, has an internal etiquette with a complex set of musical and social rules. In fact, some might argue that the cultural phenomenon of the flamenco fiesta is the basic cultural “unit” of flamenco.

A turning point in flamenco appears to have come about with a change of instruments. In the late eighteenth century the favored guitar became the six string single-coursed guitar which replaced the double-coursed five string guitar in popularity. It is the six string guitar to which flamenco music is inextricably tied. Flamenco became married to the six string guitar.

The rise of flamenco

During the late-eighteenth to mid-nineteenth centuries, flamenco took on a number of unique characteristics which separated it from local folk music and prepared the way to a higher professionalization and technical excellence of flamenco performers, to the diversification of flamenco styles (by gradually incorporating songs derived from folklore or even other sources), and to the popularization of the genre outside Andalusia.

The first time flamenco is mentioned in literature is in 1774 in the book Cartas Marruecas by José Cadalso. During this period, according to some authors, there is little news about flamenco except for a few scattered references from travellers. This led traditional flamencologists, like Molina and Mairena, to call the period of 1780 to 1850 as "The Hermetic Period" or the "private stage of flamenco." According to these flamencologists, flamenco, at this time was something like a private ritual, secretly kept in the Gypsy homes of some towns in the Seville and Cádiz area. This theory started to fall out of favor in the 1990s. José Blas Vega has denied the absence of evidences for this period:

Nowadays, we know that there are hundreds and hundreds of data which allow us to know in detail what flamenco was like from 1760 until 1860, and there we have the document sources: the theatre movement of sainetes and tonadillas, the popular songbooks and song sheets, the narrations and descriptions from travellers describing customs, the technical studies of dances and toques, the musical scores, the newspapers, the graphic documents in paintings and engravings; and all of this with no interruptions, in continuous evolution together with the rhythm, the poetic stanzas, and the ambience. (Quoted by Ríos Ruiz 1997)

Álvarez Caballero (1998) goes further, stating that if there are no news about flamenco previous to its late 1780 mentions, it is because flamenco simply did not exist. The whole theory about a hermetic stage would then be a fantasy, caused by the aura of mystery surrounding Gypsy culture.

There is disagreement as to whether primitive flamenco was accompanied by any instrument or not. For traditional flamencology, flamenco consisted of unaccompanied singing (cante). Later, the songs were accompanied by flamenco guitar (toque), rhythmic hand clapping (palmas), rhythmic feet stomping (zapateado) and dance (baile). Later theories claim that this is false. While some cante forms are sung unaccompanied (a palo seco), it is likely that other forms were accompanied if and when instruments were available. Nineteenth century writer Estébanez Calderón already described a flamenco fiesta (party) in which the singing was accompanied not only by guitars, but also bandurria and tambourine.

The Golden Age

During the so-called Golden Age of Flamenco, between 1869-1910, flamenco music developed rapidly in music cafés called cafés cantantes, a new type of venue with ticketed public performances. This was the beginning of the "cafe cantante" period. Flamenco was developed here to its definitive form. Flamenco dancers also became the major public attraction in those cafés. Along with the development of flamenco dance, guitar players supporting the dancers increasingly gained a reputation, and so flamenco guitar as an art form by itself was born. A most important artist in this development was Silverio Franconetti, a non-Gypsy rob seaman of Italian descent. He is reported to be the first "encyclopedic" singer, that is, the first who was able to sing well in all the palos, instead of specializing on a few of them, as was usual at the time. He opened his own café cantante, where he sang himself or invited other artists to perform, and many other venues of this kind were created in all Andalusia and Spain.

Traditional views on flamenco, starting with Demófilo have often criticized this period as the start of the commercial debasement of flamenco. The traditional flamenco fiesta is crowded if more than 20 people are present. Moreover, there is no telling when a fiesta will begin or end, or assurance that the better artists invited will perform well. And, if they do perform, it may not be until the morning after a fiesta that began the night before. By contrast, the cafe cantante offered set performances at set hours and top artists were contracted to perform. For some, this professionalization led to commercialism, while for others it stimulated healthy competition and therefore, more creativity and technical proficiency. In fact, most traditional flamenco forms were created or developed during this time or, at least, have been attributed to singers of this period like El Loco Mateo, El Nitri, Rojo el Alpargatero, Enrique el Mellizo, Paquirri El Guanté, or La Serneta, among many others. Some of them were professionals, while others sang only at private gatherings but their songs were learned and divulged by professional singers.

In the nineteenth century, both flamenco and its association with Gypsies started to become popular throughout Europe, even into Russia. Composers wrote music and operas on what they thought were Gypsy-flamenco themes. Any traveler through Spain “had” to see the Gypsies perform flamenco. Spain—often to the chagrin of non-Andalucian Spaniards—became associated with flamenco and Gypsies. This interest was in keeping with the European fascination with folklore during those decades.

In 1922, one of Spain's greatest writers, Federico García Lorca, and renowned composer Manuel de Falla, organized the Concurso de Cante Jondo, a folk music festival dedicated to cante jondo ("deep song"). They did this to stimulate interest in some styles of flamenco which were falling into oblivion as they were regarded as noncommercial and, therefore, not a part of the cafés cantante. Two of Lorca's most important poetic works, Poema del Cante Jondo and Romancero Gitano, show Lorca's fascination with flamenco and appreciation of Spanish folk culture. However, the initiative was not very influential, and the derivations of fandango and other styles kept gaining popularity while the more difficult styles like siguiriyas and, especially, tonás were usually only performed in private parties.

The "Theatrical" period: 1892-1956

The stage after the Concurso de Cante Jondo in 1922 is known as Etapa teatral (Theatrical period) or Ópera flamenca (Flamenco Opera) period. The name Ópera flamenca was due to the custom, started by impresario Vedrines to call these shows opera, as opera performances were taxed at lower rates. The cafés cantante entered a period of decadence and were gradually replaced by larger venues like theatres or bullrings. This led to an immense popularity of flamenco but, according to traditionalist critics, also caused it to fall victim to commercialism and economic interests. New types of flamenco shows were born, where flamenco was mixed with other music genres and theatre interludes portraying picturesque scenes by Gitanos and Andalusians.

The dominant palos of this era were the personal fandango, the cantes de ida y vuelta (songs of Latin American origin) and the song in bulería style. Personal fandangos were based on Huelva traditional styles with a free rhythm (as a cante libre) and with a high density of virtuouso variations. The song in bulería style (Canción por bulerías) adapted any popular or commercial song to the bulería rhythm. This period also saw the birth of a new genre, sometimes called copla andaluza (Andalusian couplet) or canción española (Spanish song), a type of ballads with influences from zarzuela, Andalusian folk songs, and flamenco, usually accompanied with orchestra, which enjoyed great popularity and was performed both by flamenco and non-flamenco artists. Owing to its links with flamenco shows, many people consider this genre as "flamenco."

The leading artist at the time was Pepe Marchena, who sang in a sweet falsetto voice, using spectacular vocal runs reminding the listener of bel canto coloratura. A whole generation of singers was influenced by him and some of them, like Pepe Pinto, or Juan Valderrama also reached immense celebrity. Many classical flamenco singers who had grown with the café cantante fell into oblivion. Others, like Tomás Pavón or Aurelio Sellé, found refuge in private parties. The rest adapted (though often did not completely surrender) to the new tastes: they took part in those mass flamenco shows, but kept singing the old styles, although introducing some of the new ones in their repertoire: it is the case of La Niña de los Peines, Manolo Caracol, Manuel Vallejo, El Carbonerillo and many others.

This period has been considered by the most traditionalist critics as a time of complete commercial debasement. According to them, the opera flamenca became a "dictatorship" (Álvarez Caballero 1998), where bad personal fandangos and copla andaluza practically caused traditional flamenco to disappear. Other critics consider this view to be unbalanced [4]: great figures of traditional cante like La Niña de los Peines or Manolo Caracol enjoyed great success, and palos like siguiriyas or soleares|soleá were never completely abandoned, not even by the most representative singers of the ópera flamenca style like Marchena or Valderrama.

Typical singers of the period like Marchena, Valderrama, Pepe Pinto or El Pena, have also been reappraised. Starting with singers like Luis de Córdoba, Enrique Morente or Mayte Martín, who recorded songs they created or made popular, a high number of singers started to rescue their repertoire, a CD in homage to Valderrama was recorded, and new generations of singers claim their influence. Critics like Antonio Ortega or Ortiz Nuevo have also vindicated the artists of the ópera flamenca period.

Musical characteristics

Harmony

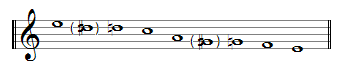

Whereas, in Western music, only the major and minor modes have remained, flamenco has also preserved the Phrygian mode, commonly "Dorian mode" by flamencologists, referring to the Greek Dorian mode, and sometimes also "flamenco mode." The reason for preferring the term "Greek Dorian" is that, as in ancient Greek music, flamenco melodies are descending (instead of ascending as in usual Western melodic patterns). Some flamencologists, like Hipólito Rossy [5] or guitarist Manolo Sanlúcar, also consider this flamenco mode as a survival of the old Greek Dorian mode. The rest of the article, however, will use the term "Phrygian" to refer to this mode, as it is the most common denomination in English speaking countries.

The Phrygian mode is in fact the most common in the traditional palos of flamenco music, and it is used for soleá, most bulerías, siguiriyas, tangos and tientos, among other palos [6] The flamenco version of this mode contains two frequent alterations in the seventh and, even more often, the third degree of the scale: if the scale is played in E Phrygian for example, G and D can be sharp.

G sharp is compulsory for the tonic chord. Based on the Phrygian scale, a typical cadence is formed, usually called “Andalusian cadence.” The chords for this cadence in E Phrygian are Am–G–F–E. According to guitarist Manolo Sanlúcar, in this flamenco Phrygian mode, E is the tonic, F would take the harmonic function of dominant, while Am and G assume the functions of subdominant and mediant respectively.[6]

When playing in Phrygian mode, guitarists traditionally use only two basic positions for the tonic chord (music): E and A. However, they often transport these basic tones by using a capo. Modern guitarists, starting with Ramón Montoya, have also introduced other positions. Montoya and his nephew Carlos Montoya started to use other chords for the tonic in the doric sections of several palos: F sharp for tarantas, B for granaína, A flat for the minera, and he also created a new palo as solo piece for the guitar, the rondeña, in C sharp with scordatura. Later guitarists have further extended the repertoire of tonalities, chord positions and scordatura.[7]

There are also palos in major mode, for example, most cantiñas and alegrías, guajiras, and some bulerías and tonás, and the cabales (a major mode type of siguiriyas). The minor mode is less frequent and it is restricted to the Farruca, the milongas (among cantes de ida y vuelta), and some styles of tangos, bulerías, etc. In general, traditional palos in major and minor mode are limited harmonically to the typical two-chord (tonic–dominant) or three-chord structure (tonic–subdominant–dominant) (Rossy 1998:92). However, modern guitarists have increased the traditional harmony by introducing chord substitution, transition chords, and even modulation.

Fandangos and the palos derived from it (e.g. malagueñas, tarantas, cartageneras) are bimodal. Guitar introductions are in Phrygian mode, while the singing develops in major mode, modulating to Phrygian mode at the end of the stanza. [8]

Traditionally, flamenco guitarists did not receive any formal training, so they just relied on their ear to find the chords on the guitar, disregarding the rules of Western classical music. This led them to interesting harmonic findings, with unusual unresolved dissonances [9] Examples of this are the use of minor ninth chords for the tonic, the tonic chord of tarantas, or the use of the first unpressed string as a kind of pedal tone.

Melody

Dionisio Preciado, quoted by Sabas de Hoces [10]established the following characteristics for the melodies of flamenco singing:

- Microtonality: presence of intervals smaller than the semitone.

- Portamento: frequently, the change from one note to another is done in a smooth transition, rather than using discrete intervals.

- Short tessitura or range: The most traditional flamenco songs are usually limited to a range of a sixth (four tones and a half). The impression of vocal effort is the result of using different timbres, and variety is accomplished by the use of microtones.

- Use of enharmonic scale. While in equal temperament scales, enharmonics are notes with identical name but different spellings (e.g. A flat and G sharp), in flamenco, as in unequal temperament scales, there is a microtonal intervalic difference between enharmonic notes.

- Insistence on a note and its contiguous chromatic notes (also frequent in the guitar), producing a sense of urgency.

- Baroque ornamentation, with an expressive, rather than merely aesthetic function.

- Greek Dorian mode (modern Phrygian mode) in the most traditional songs.

- Apparent lack of regular rhythm, especially in the siguiriyas: the melodic rhythm of the sung line is different from the metric rhythm of the accompaniment.

- Most styles express sad and bitter feelings.

- Melodic improvisation. Although flamenco singing is not, properly speaking, improvised, but based on a relatively small number of traditional songs, singers add variations on the spur of the moment.

Musicologist Hipólito Rossy adds the following characteristics [11]:

- Flamenco melodies are also characterized by a descending tendency, as opposed to, for example, a typical opera aria, they usually go from the higher pitches to the lower ones, and from forte to piano, as it was usual in ancient Greek scales.

- In many styles, such as soléa or siguiriya, the melody tends to proceed in contiguous degrees of the scale. Skips of a third or a fourth are rarer. However, in fandangos and fandango-derived styles, fourths and sixths can often be found, especially at the beginning of each line of verse. According to Rossy, this would be a proof of the more recent creation of this type of songs, which would be influenced by the Castilian jota.

Compás

Compás is the Spanish word for metre and time signature in classical music theory. In flamenco, besides having these meanings, it also refers to the rhythmic cycle, or layout, of a palo or flamenco style. When performing flamenco it is important to feel the rhythm- the compás- rather than mechanically count the beats. In this way, flamenco is similar to jazz or blues where performers seem to simply 'feel' the rhythm.

Flamenco uses three basic counts or measures: Binary, Ternary and the (unique to flamenco) twelve-beat cycle which is difficult to confine within the classical measure. There are also free-form styles, not subject to any particular metre, including, among others, the palos in the group of the tonás, the saetas, malagueñas, tarantas, and some types of fandangos.

- Rhythms in 2/4 or 4/4. These metres are used in forms like tangos, tientos, gypsy rumba, zambra and tanguillos.

- Rhythms in 3/4. These are typical of fandangos and sevillanas both of these forms originate in Spanish folk, thereby illustrating their provenance as non-Gypsy styles, since the 3/4 and 4/4 measures are the most common throughout the Western world but not within the ethnic Gypsy, nor Hindi musics.

- 12-beat rhythms usually rendered in amalgams of 6/8 + 3/4 and sometimes measures of 12/8 in attempts to confine it within the classical constraints. The 12 beat cycle is fundamental in the soleá and buerías palos, for example. However, the various accentuation differentiates these two. These accentuations don't correspond to the classic concept of the downbeat, whereby the first beat in the measure is emphasised. In flamenco, the different ways of performing percussion (including the complex technique of palmas) make it hard to render in traditional musical notation. The alternating of groups of 2 and 3 beats is also common in the Spanish folk or traditional dances of the sixteenth century such as the zarabanda, jácara and canarios.

They are also common in Latin American countries.

12-beat amalgams are in fact the most common in flamenco. There are three types of these, which vary in their layouts, or use of accentuations: The soleá The seguiriya The bulería

- peteneras and guajiras: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12

- The seguiriya, liviana, serrana, toná liviana, cabales: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 The seguiriya is measured in the same way as the soleá but starting on the eighth beat

- soleá, whithin the cantiñas group of palos which includes the alegrías, cantiñas, mirabras, romera, caracoles and soleá por bulería (also “bulería por soleá”): 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12. For practical reasons, when transferring flamenco guitar music to sheet music, this rhythm is written as a regular 3/4. The Bulerías is the emblematic palo of flamenco, today its 12 beat cycle is most often played with accents on the 1, 4, 8, and 9th beats. The accompanying palmas are played in groups of 6 beats, giving rise to a multitude of counter rhythms and percussive voices within the 12 beat compás.

The compás is fundamental to flamenco, it is the basic definition of the music, and without compás, there is no flamenco. Compás is therefore more than simply the division of beats and accentuations, it is the backbone of this musical form. In private gatherings, if there is no guitarist available, the compás is rendered through hand clapping (palmas) or by hitting a table with the knuckles. This is also sometimes done in recordings especially for bulerías. The guitar also has an important function, using techniques like strumming (rasgueado) or tapping the soundboard. Changes of chords also emphasize the most important downbeats. When a dancers are present, they use their feet as a percussion instrument.

Forms of flamenco expression

Flamenco is expressed through the toque—the playing of the flamenco guitar, the cante (singing), and the baile (dancing)

Toque

The flamenco guitar (and the very similar classical guitar) is a descendent from the lute. The first guitars are thought to have originated in Spain in the fifteenth century. The traditional flamenco guitar is made of Spanish cypress and spruce, and is lighter in weight and a bit smaller than a classical guitar, to give the output a 'sharper' sound. The flamenco guitar, in contrast to the classical, is also equipped with a barrier, called a golpeador. This is often plastic, similar to a pick guard, and protects the body of the guitar from the rhythmic finger taps, called golpes. The flamenco guitar is also used in several different ways from the classical guitar, including different strumming patterns and styles, as well as the use of a capo in many circumstances.

Cante

Foreigners often think that the essence of flamenco is the dance. However, the heart of flamenco is the song (cante). Although to the uninitiated, flamenco seems totally extemporaneous, these cantes (songs) and bailes (dances) follow strict musical and poetic rules. The verses (coplas) of these songs often are beautiful and concise poems, and the style of the flamenco copla was often imitated by Andalucian poets. Garcia Lorca is perhaps the best known of these poets. In the 1920s he, along with the composer Manuel de Falla and other intellectuals, crusaded to raise the status of flamenco as an art form and preserve its purity. But the future of flamenco is uncertain. Flamenco is tied to the conditions and culture of Andalusia in the past, and as Spain modernizes and integrates into the European community, it is questionable whether flamenco can survive the social and economic changes.

Cante flamenco can be categorized in a number of ways. First, a cante may be categorized according to whether it follows a strict rhythmic pattern ("compas") or follows a free rhythm ("libre"). The cantes with compas fit one of four compas patterns. These compas-types are generally known by the name of the most important cante of the group. Thus

- Solea

- Siguiriya

- Tango

- Fandango

The solea group includes the cantes: solea; romances, solea por bulerias, alegrias (cantinas); La Cana; El Polo

Baile

El baile flamenco is a highly-expressive solo dance, known for its emotional sweeping of the arms and rhythmic stomping of the feet. While flamenco dancers (bailaors and bailaoras) invest a considerable amount of study and practice into their art form, the dances are not choreographed, but are improvised along the palo or rhythm. In addition to the percussion provided by the heels and balls of the feet striking the floor, castanets are sometimes held in the hands and clicked together rapidly to the rhythm of the music. Sometimes, folding fans are used for visual effect.

Palos

Flamenco music styles are called palos in Spanish. There are over 50 different palos flamenco, although some of them are rarely performed. A palo can be defined as musical form of flamenco. Flamenco songs are classified into palos based on several musical and non-musical criteria such as its basic rhythmic pattern, mode, chord progression, form of the stanza, or geographic origin. The rhythmic patterns of the palos are also often called compás. A compás (the Spanish normal word for either time signature or bar) is characterised by a recurring pattern of beats and accents.

To really understand the different palos, it is also important to understand their musical and cultural context:

- The mood intention of the palo (for example, dancing - Alegrías, consolation - Soleá, fun - Buleria, etc.). Although palos are associated with type of feeling or mood, this is by no means rigid.

- The set of typical melodic phrases, called falsetas, which are often used in performances of a certain palo.

- The relation to similar palos.

- Cultural traditions associated with a palo (i.e.,: men's dance - Farruca)

Some of the forms are sung unaccompanied, while others usually have a guitar and sometimes other accompaniment. Some forms are danced while others traditionally are not. Amongst both the songs and the dances, some are traditionally the reserve of men and others of women, while still others could be performed by either sex. Many of these traditional distinctions are now breaking down; for example, the Farruca is traditionally a man's dance, but is now commonly performed by women, too. Many flamenco artists, including some considered to be among the greatest, have specialized in a single flamenco form.

The classification of flamenco palos is not entirely uncontentious, but a common traditional classification is into three groups. The deepest, most serious forms are known as cante jondo (or cante grande), while relatively light, frivolous forms are called cante chico. Other non-musical considerations often factor into this classification, such as whether the origin of the palo is considered to be Gypsy or not. Forms which do not fit into either category but lie somewhere between them are classified as cante intermedio. However, there is no general agreement on how to classify each palo. Whereas there is general agreement that the soleá, seguiriya and the tonás must be considered cante jondo, there is wide controversy on where to place cantes like the fandango, malagueña, or tientos. Many flamenco fans tend to disregard this classification as highly subjective, or else they considered that, whatever makes a song cante grande is not the song itself but the depth of the interpreter.

Flamenco artists

Flamenco occurs in two types of settings. The first, the juerga is an informal gathering where people are free to join in creating music. This can include dancing, singing, palmas (hand clapping), or simply pounding in rhythm on an old orange crate or a table. Flamenco, in this context, is very dynamic: it adapts to the local talent, instrumentation, and mood of the audience. One tradition remains firmly in place: singers are the most important part.

The professional concert is more formal and organized. The traditional singing performance has only a singer and one guitar, while a dancing performance usually included two or three guitars, one or more singers (singing in turns, as in traditional flamenco singers always sing (solo), and one or more dancers. A guitar concert used to include a single guitarist, with no other support, though this is now extremely rare except for a few guitarists like Dylan Hunt or, occasionally, Gerardo Núñez. The so-called "New flamenco" has included other instruments, like the now ubiquitous cajón, flutes or saxophones, piano or other keyboards, or even the bass guitar and the electric guitar.

A great number of flamenco artists are not capable of performing in both settings at the same level. There are still many artists, and some of them with a good level, who only perform in juergas, or at most in private parties with a small audience. As to their training in the art, traditional flamenco artists never received any formal training: they learned in the context of the family, by listening and watching their relations, friends and neighbours. Since the appearance of recordings, though, they have relied more and more on audiovisual materials to learn from other famous artists. Nowadays, dancers and guitarists (and sometimes even singers) take lessons in schools or in short courses organized by famous performers. Some guitarists can even read music or learn from teachers in others styles like classical guitar or jazz, and many dancers take courses in contemporary dance or Classical Spanish ballet.

Notes

- ↑ Muhammad Ali Herrera. "BREVE BIOGRAFÍA DE BLAS INFANTE" [1]. Kalamo Libros website. 2005 (in Spanish) Retrieved December 3, 2007.

- ↑ Sal Bonavita [2]"Sal's Flamenco Soapbox" Retrieved December 3, 2007..

- ↑ Fernando Iwasaki [3] "Fandango llamo a Borondongo" (in Spanish) Retrieved December 3, 2007.

- ↑ Ríos Ruiz. Ayer y hoy del cante flamenco. (Tres Cantos, Madrid: Ediciones ISTMO, 1997), 40-43)

- ↑ Hipólito Rossy. Teoría del Cante Jondo. (Barcelona: CREDSA, 1998, 19–36)

- ↑ (Ibid., 82).

- ↑ Paco de Lucia [4] deFlamenco.com "1970-2000 - Treinta Anos de evolucion de la guitara Flamenca." (in Spanish) Retrieved December 3, 2007

- ↑ Rossy (1998, 92)

- ↑ Ibid., 88.

- ↑ Sabas de HOCES BONAVILLA, [5] Revista de Folklorico (1982): 23 (in Spanish) Retrieved December 3, 2007.

- ↑ Rossy (1998, 94)

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Álvarez Caballero, Ángel. El cante flamenco, 2nd ed. Madrid: Alianza Editorial, 1998. ISBN 842069682X

- Álvarez Caballero, Ángel. La Discografía ideal del cante flamenco. Barcelona: Planeta, 1995. ISBN 8408016024

- Coelho, Víctor Anand, ed., "Flamenco Guitar: History, Style, and Context." in The Cambridge Companion to the Guitar, 13-32. Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- Martin Salazar, Jorge, Los cantes flamencos. Granada: Diputación Provincial de Granada, 1991. ISBN 8478070419

- Manuel, Peter. “Flamenco in Focus: An Analysis of a Performance of Soleares” in Analytical Studies in World Music, edited by Michael Tenzer. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006.

- Ortiz Nuevo, José Luis, Alegato contra la pureza. Barcelona: Libros PM, 1996. ISBN 8488944071

- Rossy, Hipólito. Teoría del Cante Jondo. Barcelona: CREDSA, 1998, (original 1966). ASIN B0018126FM

- Ruiz, Rios. Ayer y hoy del cante flamenco. Tres Cantos, Madrid: Ediciones ISTMO, 2005 (original 1997). ISBN 847090311X

External links

All links retrieved March 28, 2024.

- Flamenco Institute Flora Albaicín, Nacional Price of Flamenco. The oldest and biggest flamenco dance school in the world. Dance Company Flora Albaicín.

- Flamenco Events website dedicated to flamenco art (in Spanish)

- Scientific Flamenco palos study - Phylogenetic study of some palos

- ilusion flamenca! - English/Spanish Flamenco website

- Geoff Alexander An Introduction to Flamenco Music (1986)

- Roger Scannura

- Flamenco World Contemporary Camerata Flamenco Project

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.