Gershom Ben Judah

| Category |

| Jews · Judaism · Denominations |

|---|

| Orthodox · Conservative · Reform |

| Haredi · Hasidic · Modern Orthodox |

| Reconstructionist · Renewal · Rabbinic · Karaite |

| Jewish philosophy |

| Principles of faith · Minyan · Kabbalah |

| Noahide laws · God · Eschatology · Messiah |

| Chosenness · Holocaust · Halakha · Kashrut |

| Modesty · Tzedakah · Ethics · Mussar |

| Religious texts |

| Torah · Tanakh · Talmud · Midrash · Tosefta |

| Rabbinic works · Kuzari · Mishneh Torah |

| Tur · Shulchan Aruch · Mishnah Berurah |

| Šł§umash ¬∑ Siddur ¬∑ Piyutim ¬∑ Zohar ¬∑ Tanya |

| Holy cities |

| Jerusalem · Safed · Hebron · Tiberias |

| Important figures |

| Abraham · Isaac · Jacob/Israel |

| Sarah · Rebecca · Rachel · Leah |

| Moses · Deborah · Ruth · David · Solomon |

| Elijah · Hillel · Shammai · Judah the Prince |

| Saadia Gaon · Rashi · Rif · Ibn Ezra · Tosafists |

| Rambam · Ramban · Gersonides |

| Yosef Albo · Yosef Karo · Rabbeinu Asher |

| Baal Shem Tov · Alter Rebbe · Vilna Gaon |

| Ovadia Yosef · Moshe Feinstein · Elazar Shach |

| Lubavitcher Rebbe |

| Jewish life cycle |

| Brit · B'nai mitzvah · Shidduch · Marriage |

| Niddah · Naming · Pidyon HaBen · Bereavement |

| Religious roles |

| Rabbi · Rebbe · Hazzan |

| Kohen/Priest · Mashgiach · Gabbai · Maggid |

| Mohel · Beth din · Rosh yeshiva |

| Religious buildings |

| Synagogue · Mikvah · Holy Temple / Tabernacle |

| Religious articles |

| Tallit · Tefillin · Kipa · Sefer Torah |

| Tzitzit · Mezuzah · Menorah · Shofar |

| 4 Species · Kittel · Gartel · Yad |

| Jewish prayers |

| Jewish services · Shema · Amidah · Aleinu |

| Kol Nidre · Kaddish · Hallel · Ma Tovu · Havdalah |

| Judaism & other religions |

| Christianity · Islam · Catholicism · Christian-Jewish reconciliation |

| Abrahamic religions · Judeo-Paganism · Pluralism |

| Mormonism · "Judeo-Christian" · Alternative Judaism |

| Related topics |

| Criticism of Judaism · Anti-Judaism |

| Antisemitism · Philo-Semitism · Yeshiva |

Gershom ben Judah, (c. 960 -1040?) was a French rabbi, best known as Rabbeinu Gershom (Hebrew: ◊®◊Ď◊†◊ē ◊í◊®◊©◊ē◊Ě, "Our teacher Gershom"), who was the founder of Talmudic studies in France and Germany. He is also known by the title Me'Or Hagolah ("The Light of the exile").

Born in Metz, France, Gershom's teacher was the French rabbi Yehudah ben Meir Hakohen, also known as Sir Leofitin. His early life is surrounded with legends of his supposed adventures in the East, which are of dubious historicity. Gershom established a yeshiva in Mainz, Germany, which soon became the leading Talmudic academy of Europe, rivaling the great schools of the Jewish community of Babylonia. Among his many disciples were the principal teachers of the great sage Rashi, especially Rabbi Jacob ben Yakar.

Around 1000 C.E. Gershom called a synod that determined several major points of Rabbinic Judaism, including the prohibition of polygamy, the necessity of the wife consenting to divorce, the compassionate treatment of Jews who became apostates under compulsion, and the prohibition of opening correspondence addressed to another. The rule against polygamy was revolutionary, in that most Jews of the time lived in Islamic countries such as Babylonia and Spain, and still held polygamy to be acceptable.

Rashi (d. 1105) declared that all of the great rabbis of his own era were "students of his (Gershom's) students." In the fourteenth century, Rabbi Asher ben Jehiel wrote that Rabbeinu Gershom's writings were "such permanent fixtures that they may well have been handed down on Mount Sinai."

Biography

Rabbeinu Gershom studied under Judah ben Meir ha-Kohen, who was one of the greatest authorities of his time. Having lost his first wife, traditionally known as Judah's daughter Deborah, Gershom married a widow named Bonna and settled at Mainz, where he devoted himself to teaching the Talmud. He had many pupils from different countries, among whom were Eleazar ben Isaac and Jacob ben Yakar, the teacher of the great rabbinical sage Rashi. The fame of Gershom's learning eclipsed even that of the heads of the Babylonian academies of the Sura and Pumbedita, which until them had been preeminent.

During Gershom's lifetime Mainz became a center of Torah and Jewish scholarship for many Jewish communities in Europe that had formerly been connected with the Babylonian yeshivas. He became the spiritual leader of the fledgling Ashkenazic Jewish communities and was very influential in molding them at a time when their already small population was dwindling.

The most difficult halakhic questions were addressed to him by Jews from all quarters, and measures which he authorized had legal force among virtually all the Jews of Europe. In about the year 1000 he called a synod which decided the following particulars:

- prohibition of polygamy

- necessity of obtaining the consent of both parties to a divorce

- showing compassion to those who became apostates under compulsion

- prohibition of opening correspondence addressed to another

The first two of these are recognized as milestones of women's rights in Jewish tradition.

Gershom was also an active writer. He is celebrated for his works in the field of biblical exegesis, the Masorah (textual criticism), and lexicography. He revised and clarified the text of both the Mishnah and Talmud, the fundamental texts of rabbinical Judaism. He also wrote commentaries on several treatises of the Talmud which were very popular and provided the impulse for the production of many other works of the kind.

Gershom also composed poetic penitential prayers, which were inspired by the bloody persecutions of his time, warning the people against sin. He is the author of Seliha 42‚ÄĒZechor Berit Avraham ("Remember the Covenant of Abraham")‚ÄĒa liturgical poem recited by Ashkenazic Jews during the season of Rosh HaShana and Yom Kippur:

- "The Holy City and its regions

- are turned to shame and to spoils

- and all its desirable things are buried and hidden

- and nothing is left except this Torah."

Gershom also left a large number of rabbinical responsa, which are scattered throughout various collections. His life reportedly conformed to his teachings.

Man of tolerance

Rabbeinu Gershom reportedly had a son who forsook the Jewish religion and became a Christian at the time of the expulsion of the Jews from Mainz in 1012. The young man later died before his father, without having returned to Judaism. Refusing to disown him spiritually, as many others would have done, Gershom grieved for his son, observing all the forms of Jewish mourning. His example in this regard became a rule for others in similar cases.

His tolerance also extended to those who had submitted to baptism to escape persecution and who afterward returned to the Jewish fold. He strictly prohibited reproaching them for their apostasy, and even gave those among them who had been slandered an opportunity to pray publicly in the synagogues.

Legends

As with many of the great rabbis of this and other periods, the life of Rabbeinu Gershom is surrounded with wonderful legends.

The story goes that as a young man, he had already won great renown as a scholar and example of righteousness. His teacher, Judah ben Me√Įr ha-Kohen, esteemed him so highly that he gave Gershom the hand of his daughter Deborah in marriage.

Soon after this Gershom and Deborah traveled to the Babylonian city of Pumbedita, where the renowned Sherira Gaon headed perhaps the greatest Talumdic academy in the world. The journey there was full of hardship and adventures.

In Pumbedita, Gershom spent several happy years devoting himself to the study of the Torah and Talmud. When he reached the point of becoming a teacher himself, he did not want to profit from his knowledge, but labored as a goldsmith, developing marvelous skill in this trade and settling in the great city of Constantinople, the most important trading center of the East.

While there, a tremendous fire swept through the city, leaving it in ruin, followed almost immediately by a horrible plague. Victims lay dying everywhere in the city's streets. Rabbeinu Gershom refused to sit passively and witness the suffering of his fellow men, even though they were not Jews. He had some knowledge of medicine as a result of his studies, and with utter selflessness he ministered to the sick.

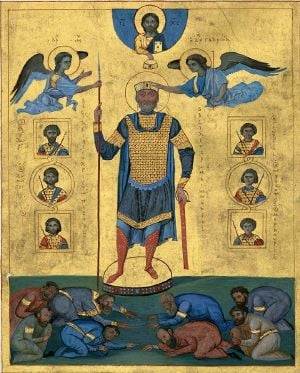

The Byzantine emperor Basil II ruled at Constantinople during this time. Although he personally was a good man, he was easily misled by his advisers, especially a certain John, and unrelenting Jew-hater. When the emperor consulted his advisers concerning the fire an plague, John blamed the Jews, ultimately persuading Basil to issue a decree expelling the Jews and confiscating their property.

Soon after this, however, Basil's daughter fell desperately ill. The greatest physicians of the empire were summoned to the palace to heal her, but none of them could effect a cure. When the news of the sick princess reached Rabbeinu Gershom, he immediately set out for the palace, despite the risk. According to the legend, Basil told him: "If you succeed in curing the princess I will reward you generously, but if you fail, you will lose your head!"

Gershom examined the princess, but he quickly realized that he was beyond human help. Only a miracle could save her. Gershom prayed to God with all his heart. "O G-d," he implored, "save this girl, for the sake of your people."

The color immediately came back to her, and with each day she grew stronger. The overjoyed emperor and empress were filled with gratitude to Gershom, and Basil offered him a rich reward of luxurious wealth. Gershom replied that the greatest reward he could receive would be the withdrawal of the decree against the Jews. Basil agreed, and soon the decree was annulled.

The Silver Throne

Gershom now became Basil II's friend and close confident. One day, Gershom happened to tell the emperor the story of Solomon's wonderful golden throne. Knowing Gershom to be a goldsmith, Basil asked him to create such a throne for him. However, it turned our that there was not enough gold in the king's treasury for the task, so the throne was thus fashioned out of silver. So complicated was the task that it took several years to complete. When it was finished, a great festival was planned to celebrate its unveiling.

However, as Basil ascended the magnificent throne, he became confused about the operation of its marvelous hidden mechanisms. He thus asked Rabbeinu Gershom to ascend the throne before him and show him how it worked. Six silver steps led up the throne, each one flanked by two different animals, all cast of silver. As Gershom ascended, the animals marvelously extended their feet to support him. When he had reached the last step and took his seat, a huge silver eagle held the royal crown over Gershom's head. The courtiers broke out into enthusiastic cheers and applause. Gershom then descended and received the emperor's thanks, Basil proceeded to mount the throne and take his proper place.

The evil minister John, however, so jealous of Gershom's success that he determined to find a way to do away with him. John knew that some of the workmen had stolen silver during the throne's construction and conceived a plan to lay the blame on Gershom. "Let us weigh the throne and ascertain the truth," he told the king. Basil agreed, but there was no scale large enough to weigh the throne. The empire's greatest engineers all attempted to create a way to weigh the throne, but they all failed.

The one thing that brought sadness to Rabbeinu Gershom's heart was the fact that he had no children. His wife, like the matriarchs of the Bible, was barren, thus she encouraged him to take a second wife by whom he could perpetuate his lineage. This woman had many acquaintances in the royal household. Like Delilah before her, she used every possible womanly wile and finally succeeded in coaxing from him the secret of how to weigh the throne‚ÄĒby placing the throne in a boat and measuring the displacement of water which this created.

The woman, of course, immediately divulged the secret. When the throne was weighed, John's accusation seemed proven to be true, for the throne weighed substantially less than it should have. Basil summoned Gershom and informed him of the charges against him. Gershom explained that it must have been the workmen who stole the silver, but the emperor was now completely taken in by the evil John. He condemned Gershom to die unless agreed to be baptized as a Christian. Gershom refused to apostatize, and prepared to die. His one "consolation" was that, because he had saved the king's daughter, he would not be hanged, but would be imprisoned in a tower in an isolated desert. There, without any food or drink, he would starve to death.

Imprisoned in the tower, Gershom heard the sound of a woman crying. He looked out and saw his true wife, Deborah. "I have come to die with you," she said in tears. "I am glad you have come," Gershom replied, "but not to die with me. Find a woodworm and a beetle. Then get some silk thread, cord, and rope. Tie the silk thread about the beetle. Then tie the cord to the silk thread, and tie the rope to the cord. Let the worm crawl up the side of the tower and the beetle will pursue it, bringing the rope up to me."

About a week later, the wicked John awoke from his sleep and determined to go to the desert and satisfy himself that the Gershom had died. Taking the keys to the tower with him, John climbed up and opened the Gershom's cell, only to find it empty. In his shock, he allowed the door to close, and the key was still in the lock outside! He used all of his strength, but was unable to force it open. There, he himself began to suffer the fate originally intended for Gershom.

Rabbenu Gershom, meanwhile, stood with Deborah on the deck of a ship nearing the shores of his native land in France. Thus ends the legend. The rest, so they say, is history.

Legacy

Meor Hagolah (The Light of the Exile) is a fitting title for Rabbenu Gershom. He became a beacon of light for the Jews of the European diaspora. His yeshiva became the leading center of Jewish learning for the fledging Jewish community of France and Germany. Soon, through the work of such a gigantic figure as Rashi, his tradition would be enshrined for generations.

The halakhic rulings of Gershom Ben Judah are considered binding on all of Ashkenazic Jewry until the present day, although the basis for this is somewhat controversial. Some hold that his bans are still binding and others consider them to have technically expired but believe they nonetheless remain obligatory as universally accepted customs.

Some have speculated that if Rabbeinu Gershom had never lived, there may never have ever been what is today known as "Ashkenazic Judaism." In the words of the renowned Rashi (1040‚Äď1105), all of the great European rabbis of the coming generation were ‚Äústudents of his students.‚ÄĚ

See also

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

This article incorporates text from the 1901‚Äď1906 Jewish Encyclopedia, a publication now in the public domain.

- Biale, David. Cultures of the Jews: A New History. Schoken Books, 2002. ISBN 0805241310

- Lehmann, Marcus. Rabbenu Gershom; Meor Hagolah, Light of the Exile. Brooklyn, N.Y.: Merkos L'inyonei Chinuch, 1968. OCLC 19565653

- Petuchowski, Aaron M. Inconsistency for Good Reason: The Responsa of Rabbenu Gershom. New York: Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion, 1983. OCLC 84994988

- Shereshevsky, Esra. Rashi, the Man and His World. New York: Sepher-Hermon Press, 1982. ISBN 9780872031012

- Vital, David. A People Apart: A History of the Jews in Europe. Oxford University Press, 1999. ISBN 0198219806

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.