Wilhelm II ; Prince Frederick William Victor Albert of Prussia (January 27, 1859 – June 4, 1941) was the third and last German Emperor and the ninth and last King of Prussia (German: Deutscher Kaiser und König von Preußen), ruling both the German Empire and the Kingdom of Prussia from June 15, 1888 to November 9, 1918. A proponent of German expansion and imperialism, he wanted the recently unified Germany (1871), arrived late on the stage of rival European powers, to acquire an empire that would match those of France, Great Britain, the Netherlands, Spain and Portugal. Leading Germany into World War I, his ability to direct Germany's military affairs declined and he relied increasingly on his generals. His abdication took place a few days before the ceasefire that effectively ended the war with Germany's defeat. He was given asylum in the Netherlands, writing his memoirs and engaging in amateur archeology in Cyprus.

His role in World War I is debated by scholars. On the one hand, he was unhappy with the scale of the war. On the other hand, he could have halted German participation if he had wanted to, since he exercised final decision-making authority. If a genuinely democratic system had developed in Germany, war may well have been averted. It was Germany's leaders, not the German people, who took the state into war. However, the economy of that state was designed and geared for war; Germany was less a state with an army than an army with a state. Prioritizing diplomacy over conflict was regarded as a weakness. The ultimate lesson that Wilhelm II's life teaches humanity is that countries that equip for war end up at war. Countries that make trade, not military capability, their priority are more likely to value peace and to work to make peace a permanent reality, as have the nations of the post-World War II European space.

Family background

Wilhelm II was born in Berlin to Prince Frederick William of Prussia and his wife, Victoria, Princess of Prussia (born Princess Royal of the United Kingdom), thus making him a grandson of Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom. He was Queen Victoria's first grandchild. As the son of the Crown Prince of Prussia, Wilhelm was (from 1861) the second in the line of succession to Prussia, and also, after 1871, to the German Empire, which according to the constitution of the German Empire was ruled by the Prussian King. As with most Victorian era royalty, he was related to many of Europe's royal families.

A traumatic breech birth left him with a withered left arm due to Erb's Palsy, which he tried with some success to conceal. In many photos he carries a pair of white gloves in his left hand to make the arm seem longer, or has his crippled arm on the hilt of a sword or clutching a cane to give the effect of the limb being posed at a dignified angle.

Early years

Wilhelm was educated at Kassel at the Friedrichsgymnasium and the University of Bonn. Wilhelm possessed a quick intelligence, but unfortunately this was often overshadowed by a cantankerous temper. Wilhelm also took a certain interest in the science and technology of the age, but though he liked to pose, in conversation, as a man of the world, he remained convinced that he belonged to a distinct order of mankind, designated for monarchy by the grace of God. Wilhelm was accused of megalomania as early as 1892, by the Portuguese man of letters Eça de Queiroz, then in 1894 by the German pacifist Ludwig Quidde.

As a scion of the Royal House of Hohenzollern, Wilhelm was also exposed from an early age to the military society of the Prussian aristocracy. This had a major impact on him and, in maturity, Wilhelm was seldom to be seen out of uniform. The hyper-masculine military culture of Prussia in this period did much to frame Wilhelm's political ideals as well as his personal relationships.

Wilhelm's relationship with the male members of his family was as interesting as that with his mother. Crown Prince Frederick was viewed by his son with a deeply felt love and respect. His father's status as a hero of the wars of unification was largely responsible for the young Wilhelm's attitude, as in the circumstances in which he was raised; close emotional contact between father and son was not encouraged. Later, as he came into contact with the Crown Prince's political opponents, Wilhelm came to adopt more ambivalent feelings toward his father, given the perceived influence of Wilhelm's mother over a figure who should have been possessed of masculine independence and strength. Wilhelm also idolized his grandfather, Wilhelm I, and he was instrumental in later attempts to foster a cult of the first German Emperor as "Wilhelm the Great."

In many ways, Wilhelm was a victim of his inheritance and of Otto von Bismarck's machinations. Both sides of his family had suffered from mental illness, and this may explain his emotional instability. The Emperor's parents, Frederick and Victoria, were great admirers of the Prince Consort of the United Kingdom, their father-in-law and father, respectively. They planned to rule as consorts, like Albert and Queen Victoria, and they planned to reform the fatal flaws in the executive branch that Bismarck had created for himself. The office of Chancellor responsible to the Emperor would be replaced with a British-style cabinet, with ministers responsible to the Reichstag. Government policy would be based on the consensus of the cabinet.

When Wilhelm was a teenager, Bismarck separated him from his parents and placed him under his tutelage. Bismarck planned to use Wilhelm as a weapon against his parents in order to retain his own power. Bismarck drilled Wilhelm on his prerogatives and taught him to be insubordinate to his parents. Consequently, Wilhelm developed a dysfunctional relationship with his father and especially with his English mother. As it turned out, Bismarck would become the first victim of his own creation.

Next to the throne

The German Emperor Wilhelm I died in Berlin on March 9, 1888, and Prince Wilhelm's father was proclaimed Emperor as Frederick III. He was already suffering from an incurable throat cancer and spent all 99 days of his reign fighting the disease before dying. On June 15 of that same year, his 29-year-old son succeeded him as German Emperor and King of Prussia.

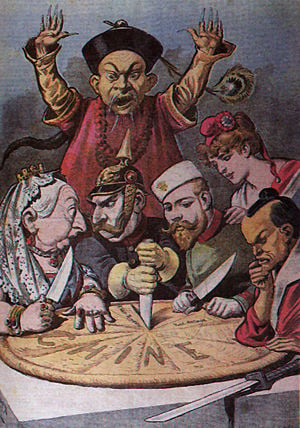

Although in his youth he had been a great admirer of Otto von Bismarck, Wilhelm's characteristic impatience soon brought him into conflict with the "Iron Chancellor," the dominant figure in the foundation of his empire. The new Emperor opposed Bismarck's careful foreign policy, preferring vigorous and rapid expansion to protect Germany's "place in the sun." Furthermore, the young Emperor had come to the throne with the determination that he was going to rule as well as reign, unlike his grandfather, who had largely been content to leave day-to-day administration to Bismarck.

Early conflicts between Wilhelm II and his chancellor soon poisoned the relationship between the two men. Bismarck believed that William was a lightweight who could be dominated, and he showed scant respect for Wilhelm's policies in the late 1880s. The final split between monarch and statesman occurred soon after an attempt by Bismarck to implement a far-reaching anti-Socialist law in early 1890.

Break with Bismarck

It was during this time that Bismarck, after gaining a favorable absolute majority toward his policies in the Reichstag, decided to make the anti-Socialist laws permanent. His Kartell majority of the amalgamated Conservative Party and the National Liberal Party was favorable to make the laws permanent with one exception: the police power to expel Socialist agitators from their homes, a power used excessively at times against political opponents. Hence, the Kartell split on this issue, with the National Liberal Party unwilling to make the expulsion clause of the law permanent. The Conservatives supported only the entirety of the bill and threatened to and eventually vetoed the entire bill in session because Bismarck wouldn't give his assent to a modified bill. As the debate continued, Wilhelm became increasingly interested in social problems, especially the treatment of mine workers who went on strike in 1889, and keeping with his active policy in government, routinely interrupted Bismarck in Council to make clear his social policy. Bismarck sharply disagreed with Wilhelm's policy and worked to circumvent it. Even though Wilhelm supported the altered anti-socialist bill, Bismarck pushed for his support to veto the bill in its entirety, but when Bismarck's arguments couldn't convince Wilhelm, he became excited and agitated until uncharacteristically blurting out his motive to see the bill fail: to have the Socialists agitate until a violent clash occurred that could be used as a pretext to crush them. Wilhelm replied that he wasn't willing to open his reign with a bloody campaign against his subjects. The next day, after realizing his blunder, Bismarck attempted to reach a compromise with Wilhelm by agreeing to his social policy towards industrial workers, and even suggested a European council to discuss working conditions, presided over by the German Emperor.

Despite this, a turn of events eventually led to his distance from Wilhelm. Bismarck, feeling pressured and unappreciated by the Emperor and undermined by ambitious advisers, refused to sign a proclamation regarding the protection of workers along with Wilhelm, as was required by the German Constitution, to protest Wilhelm's ever-increasing interference with Bismarck's previously unquestioned authority. Bismarck also worked behind the scenes to break the Continental labor council Wilhelm held so dear. The final break came as Bismarck searched for a new parliamentary majority, with his Kartell voted from power due to the anti-Socialist bill fiasco. The remaining powers in the Reichstag were the Catholic Centre Party and the Conservative Party. Bismarck wished to form a new bloc with the Centre Party, and invited Ludwig Windthorst, the party's parliamentary leader, to discuss an alliance. This would be Bismarck's last political maneuver. Wilhelm was furious to hear about Windthorst's visit. In a parliamentary state, the head of government depends on the confidence of the parliamentary majority, and certainly has the right to form coalitions to ensure his policies a majority, but in Germany, the Chancellor depended on the confidence of the Emperor alone, and Wilhelm believed that the Emperor had the right to be informed before his minister's meeting. After a heated argument in Bismarck's estate over Imperial authority, Wilhelm stormed out, both parting ways permanently. Bismarck, forced for the first time into a situation he could not use to his advantage, wrote a blistering letter of resignation, decrying Wilhelm's interference in foreign and domestic policy, which was only published after Bismarck's death. When Bismarck realized that his dismissal was imminent:

- All Bismarck’s resources were deployed; he even asked Empress Frederick to use her influence with her son on his behalf. But the wizard had lost his magic; his spells were powerless because they were exerted on people who did not respect them, and he who had so signally disregarded Kant’s command to use people as ends in themselves had too small a stock of loyalty to draw on. As Lord Salisbury told Queen Victoria: 'The very qualities which Bismarck fostered in the Emperor in order to strengthen himself when the Emperor Frederick should come to the throne have been the qualities by which he has been overthrown.' The Empress, with what must have been a mixture of pity and triumph, told him that her influence with her son could not save him for he himself had destroyed it.[1]

Bismarck resigned at Wilhelm II's insistence in 1890, at age 75, to be succeeded as Chancellor of Germany and Minister-President of Prussia by Leo von Caprivi, who in turn was replaced by Chlodwig zu Hohenlohe-Schillingsfürst in 1894.

| ||||||||||||

In appointing Caprivi and then Hohenlohe, Wilhelm was embarking upon what is known to history as "the New Course," in which he hoped to exert decisive influence in the government of the empire. There is debate amongst historians as to the precise degree to which Wilhelm succeeded in implementing "personal rule" in this era, but what is clear is the very different dynamic which existed between the Crown and its chief political servant (the Chancellor) in the "Wilhelmine Era." These chancellors were senior civil servants and not seasoned politician-statesmen like Bismarck. Wilhelm wanted to preclude the emergence of another Iron Chancellor, whom he ultimately detested as being "a boorish old killjoy" who had not permitted any minister to see the Emperor except in his presence, keeping a stranglehold on effective political power. Upon his enforced retirement and until his dying day, Bismarck was to become a bitter critic of Wilhelm's policies, but without the support of the supreme arbiter of all political appointments (the Emperor) there was little chance of Bismarck exerting a decisive influence on policy.

Something which Bismarck was able to effect was the creation of the "Bismarck myth." This was a view—which some would argue was confirmed by subsequent events—that, with the dismissal of the Iron Chancellor, Wilhelm II effectively destroyed any chance Germany had of stable and effective government. In this view, Wilhelm's "New Course" was characterized far more as the German ship of state going out of control, eventually leading through a series of crises to the carnage of the First and Second World Wars.

The strong chancellors

Following the dismissal of Hohenlohe in 1900, Wilhelm appointed the man whom he regarded as "his own Bismarck," Bernhard von Bülow. Wilhelm hoped that in Bülow, he had found a man who would combine the ability of the Iron Chancellor with the respect for Wilhelm's wishes which would allow the empire to be governed as he saw fit. Bülow had already been identified by Wilhelm as possessing this potential, and many historians regard his appointment as chancellor as being merely the conclusion of a long "grooming" process. Over the succeeding decade however, Wilhelm became disillusioned with his choice, and following Bülow's opposition to the Emperor over the "Daily Telegraph Affair" of 1908 (see below) and the collapse of the liberal-conservative coalition which had supported Bülow in the Reichstag, Wilhelm dismissed him in favor of Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg in 1909.

Bethmann Hollweg was a career bureaucrat, at whose family home Wilhelm had stayed as a youth. Wilhelm especially came to show great respect for him, acknowledging his superior foresight in matters of internal governance, though he disagreed with certain of his policies, such as his attempts at the reform of the Prussian electoral laws. However, it was only reluctantly that the Emperor parted ways with Bethmann Hollweg in 1917, during the third year of the First World War.

Wilhelm's involvement in the domestic sphere was more limited in the early twentieth century than it had been in the first years of his reign. In part, this was due to the appointment of Bülow and Bethmann—arguably both men of greater force of character than William's earlier chancellors—but also because of his increasing interest in foreign affairs.

Foreign affairs

German foreign affairs policy under Wilhelm II was faced with a number of significant problems. Perhaps the most apparent was that William was an impatient man, subjective in his reactions and affected strongly by sentiment and impulse. He was personally ill-equipped to steer German foreign policy along a rational course. It is now widely recognized that the various spectacular acts which Wilhelm undertook in the international sphere were often partially encouraged by the German foreign policy elite.[2] There were a number of key exceptions, such as the famous Kruger telegram of 1896 in which Wilhelm congratulated President Kruger of the Transvaal on the suppression of the Jameson Raid, thus alienating British public opinion. After the murder of the German ambassador during the Boxer Rebellion in 1900, a regiment of German troops was sent to China. In a speech of July 27, 1900, the Emperor exhorted these troops:

- "Just as the Huns under their king Etzel created for themselves a thousand years ago a name which men still respect, you should give the name of German such cause to be remembered in China for a thousand years ..." [3]

Though its full impact was not felt until many years later, when Entente and American propagandists shamelessly lifted the term Huns out of context, this is another example of his unfortunate propensity for impolitic public utterances. This weakness made him vulnerable to manipulation by interests within the German foreign policy elite, as subsequent events were to prove. Wilhelm had much disdain for his uncle, King Edward VII of the United Kingdom, who was much more popular as a sovereign in Europe.

One of the few times Wilhelm succeeded in personal "diplomacy" was when with he supported Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria in marrying Sophie Chotek in 1900 against the wishes of Emperor Franz Joseph. Deeply in love, Franz Ferdinand refused to consider marrying anyone else. Pope Leo XIII, Tsar Nicholas II of Russia, and Wilhelm all made representations on Franz Ferdinand's behalf to the Emperor Franz Joseph, arguing that the disagreement between Franz Joseph and Franz Ferdinand was undermining the stability of the monarchy.

One "domestic" triumph for Wilhelm was when his daughter Victoria Louise married the Duke of Brunswick in 1913; this helped heal the rift between the House of Hanover and the House of Hohenzollern after the 1866 annexation of Hanover by Prussia. In 1914, William's son Prince Adalbert of Prussia married a Princess of the Ducal House of Saxe-Meiningen. However the rifts between the House of Hohenzollern and the two leading Royal dynasties of Europe—the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha and House of Romanov—would only get worse.

Inconsistency

Following his dismissal of Bismarck, Wilhelm and his new chancellor Caprivi became aware of the existence of the secret Reinsurance Treaty with the Russian Empire, which Bismarck had concluded in 1887. Wilhelm's refusal to renew this agreement which guaranteed Russian neutrality in the event of an attack by France was seen by many historians as the worst blunder committed by Wilhelm in terms of foreign policy. In reality, the decision to allow the lapse of the treaty was largely the responsibility of Caprivi, though Wilhelm supported his chancellor's actions. It is important not to overestimate the influence of the Emperor in matters of foreign policy after the dismissal of Bismarck, but it is certain that his erratic meddling contributed to the general lack of coherence and consistency in the policy of the German Empire toward other powers.

In December 1897, Wilhelm visited Bismarck for the last time. On many occasions, Bismarck had expressed grave concerns about the dangers of improvising government policy based on the intrigues of courtiers and militarists. Bismarck’s last warning to William was:

"Your Majesty, so long as you have this present officer corps, you can do as you please. But when this is no longer the case, it will be very different for you."[4]

Subsequently, just before he died, Bismarck made these dire and accurate predictions:

"Jena came twenty years after the death of Frederick the Great; the crash will come twenty years after my departure if things go on like this"—a prophecy fulfilled almost to the month.[5]

<blockquote|One day the great European War will come out of some damned foolish thing in the Balkans."[6]

Ironically Bismarck had warned in February 1888 of a Balkan Crisis turning into a World War—although when the war came about-the Balkan country was Serbia-not Bulgaria and that it was only after World War I that war would turn into the global World War II from Moscow to the Pyrenees:

He warned of the imminent possibility that Germany will have to fight on two fronts; he spoke of the desire for peace; then he set forth the Balkan case for war and demonstrates its futility: Bulgaria, that little country between the Danube and the Balkans, is far from being an object of adequate importance… for which to plunge Europe from Moscow to the Pyrenees, and from the North Sea to Palermo, into a war whose issue no man can foresee. At the end of the conflict we should scarcely know why we had fought.[7]

A typical example of this was his "love-hate" relationship with the United Kingdom and in particular with his British cousins. He returned to England in January 1901 to be at the bedside of his grandmother, Queen Victoria, and was holding her in his arms at the moment of her death.[8] Open armed conflict with Britain was never what Wilhelm had in mind—"a most unimaginable thing," as he once quipped—yet he often gave in to the generally anti-British sentiments within the upper echelons of the German government, conforming as they did to his own prejudices toward Britain which arose from his youth. When war came about in 1914, Wilhelm sincerely believed that he was the victim of a diplomatic conspiracy set up by his late uncle, Edward VII, in which Britain had actively sought to "encircle" Germany through the conclusion of the Entente Cordiale with France in 1904 and a similar arrangement with Russia in 1907. This is indicative of the fact that Wilhelm had a highly unrealistic belief in the importance of "personal diplomacy" between European monarchs, and could not comprehend that the very different constitutional position of his British cousins made this largely irrelevant. A reading of the Entente Cordiale shows that it was actually an attempt to put aside the ancient rivalries between France and Great Britain rather than an "encirclement" of Germany.

Similarly, he believed that his personal relationship with his cousin-in-law Nicholas II of Russia (see The Willy-Nicky Correspondence) was sufficient to prevent war between the two powers. At a private meeting at Björkö in 1905, Wilhelm concluded an agreement with his cousin, which amounted to a treaty of alliance, without first consulting with Bülow. A similar situation confronted Czar Nicholas on his return to St. Petersburg, and the treaty was, as a result, a dead letter. But Wilhelm believed that Bülow had betrayed him, and this contributed to the growing sense of dissatisfaction he felt towards the man he hoped would be his foremost servant. In broadly similar terms to the "personal diplomacy" at Björkö, his attempts to avoid war with Russia by an exchange of telegrams with Nicholas II in the last days before the outbreak of the First World War came unstuck due to the reality of European power politics. His attempts to woo Russia were also seriously out of step with existing German commitments to Austria-Hungary. In a chivalrous fidelity to the Austro-Hungarian/German alliance, William informed the Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria in 1889 that "the day of Austro-Hungarian mobilization, for whatever cause, will be the day of German mobilization too." Given that Austrian mobilization for war would most likely be against Russia, a policy of alliance with both powers was obviously impossible.

The Moroccan Crisis

In some cases, Wilhelm II's diplomatic "blunders" were often part of a wider reaching policy emanating from the German governing élite. One such action sparked the Moroccan Crisis of 1905, when Wilhelm was persuaded (largely against his wishes) to make a spectacular visit to Tangier, in Morocco. Wilhelm's presence was seen as an assertion of German interests in Morocco and in a speech he even made certain remarks in favor of Moroccan independence. This led to friction with France, which had expanding colonial interests in Morocco, and led to the Algeciras Conference, which served largely to further isolate Germany in Europe.

Britain and France's alliance fortified as a corollary, namely due to the fact that Britain advocated France's endeavors to colonies Morocco, whereas Wilhelm supported Moroccan self-determination: and so, the German Emperor became even more resentful.

Daily Telegraph affair

Perhaps Wilhelm's most damaging personal blunder in the arena of foreign policy had a far greater impact in Germany than internationally. The Daily Telegraph Affair of 1908 stemmed from the publication of some of Wilhelm's opinions in edited form in the British daily newspaper of that name. Wilhelm saw it as an opportunity to promote his views and ideas on Anglo-German friendship, but instead, due to his emotional outbursts during the course of the interview, William ended up further alienating not only the British people, but also the French, Russians, and Japanese all in one fell swoop by implying, inter alia, that the Germans cared nothing for the British; that the French and Russians had attempted to incite Germany to intervene in the Second Boer War; and that the German naval buildup was targeted against the Japanese, not Britain. (One memorable quote from the interview is "You English are mad, mad, mad as March hares."[9]) The effect in Germany was quite significant, with serious calls for his abdication being mentioned in the press. Quite understandably, William kept a very low profile for many months after the Daily Telegraph fiasco, and later exacted his revenge by enforcing the resignation of Prince Bülow, who had abandoned the Emperor to public criticism by publicly accepting some responsibility for not having edited the transcript of the interview before its publication.

The Daily Telegraph crisis had deeply wounded Wilhelm's previously unimpaired self-confidence, so much so that he soon suffered a severe bout of depression from which he never really recovered (photographs of William in the post-1908 period show a man with far more haggard features and graying hair), and he in fact lost much of the influence he had previously exercised in terms of both domestic and foreign policy.

Nothing Wilhelm II did in the international arena was of more influence than his decision to pursue a policy of massive naval construction. In 1895 he opened the Kiel Canal, an event that was captured by British director Birt Acres in his film The Opening of the Kiel Canal. [10]

A powerful navy was Wilhelm's pet project. He had inherited, from his mother, a love of the British Royal Navy, which was at that time the world's largest. He once confided to his uncle, Edward VII, that his dream was to have a "fleet of my own some day." Wilhelm's frustration over his fleet's poor showing at the Fleet Review at his grandmother Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee celebrations, combined with his inability to exert German influence in South Africa following the dispatch of the Kruger telegram, led to Wilhelm taking definitive steps toward the construction of a fleet to rival that of his British cousins. Wilhelm was fortunate to be able to call on the services of the dynamic naval officer Alfred von Tirpitz, whom he appointed to the head of the Imperial Naval Office in 1897.

The new admiral had conceived of what came to be known as the "Risk theory" or the Tirpitz Plan, by which Germany could force Britain to accede to German demands in the international arena through the threat posed by a powerful battle fleet concentrated in the North Sea. Tirpitz enjoyed Wilhelm's full support in his advocacy of successive naval bills of 1897 and 1900, by which the German navy was built up to contend with that of the United Kingdom. Naval expansion under the Fleet Acts eventually led to severe financial strains in Germany by 1914, as by 1906 Wilhelm had committed his navy to construction of the much larger, more expensive dreadnought type of battleship.

World War I

The Sarajevo crisis

Wilhelm was a friend of Franz Ferdinand, Archduke of Austria-Este, and he was deeply shocked by his assassination on June 28, 1914. Wilhelm offered to support Austria-Hungary in crushing the Black Hand, the secret organization that had plotted the killing, and even sanctioned the use of force by Austria against the perceived source of the movement—Serbia (this is often called "the blank check"). He wanted to remain in Berlin until the crisis was resolved, but his courtiers persuaded him instead to go on his annual cruise of the North Sea on July 6, 1914. It was perhaps realized that Wilhelm's presence would be more of a hindrance to those elements in the government who wished to use the crisis to increase German prestige, even at the risk of general war—something of which Wilhelm, for all his bluster, was extremely apprehensive.

Wilhelm made erratic attempts to stay on top of the crisis via telegram, and when the Austro-Hungarian ultimatum was delivered to Serbia, he hurried back to Berlin. He reached Berlin on July 28, read a copy of the Serbian reply, and wrote on it:

"A brilliant solution—and in barely 48 hours! This is more than could have been expected. A great moral victory for Vienna; but with it every pretext for war falls to the ground, and [the Ambassador] Giesl had better have stayed quietly at Belgrade. On this document, I should never have given orders for mobilization."[11]

Unknown to the Emperor, Austro-Hungarian ministers and generals had already convinced the 84-year-old Francis Joseph I of Austria to sign a declaration of war against Serbia.

July 30–31, 1914

On the night of July 30–31, when handed a document stating that Russia would not cancel its mobilization, Wilhelm wrote a lengthy commentary containing the startling observations:

- "For I no longer have any doubt that England, Russia and France have agreed among themselves—knowing that our treaty obligations compel us to support Austria - to use the Austro-Serb conflict as a pretext for waging a war of annihilation against us. ... Our dilemma over keeping faith with the old and honorable Emperor has been exploited to create a situation which gives England the excuse she has been seeking to annihilate us with a spurious appearance of justice on the pretext that she is helping France and maintaining the well-known Balance of Power in Europe, i.e. playing off all European States for her own benefit against us."[12]

When it had become clear that the United Kingdom would enter the war if Germany attacked France through neutral Belgium, the panic-stricken Wilhelm attempted to redirect the main attack against Russia. When Helmuth von Moltke (the younger) told him that this was impossible, Wilhelm said: "Your uncle would have given me a different answer!!."[13]

Wilhelm is a controversial issue in historical scholarship and this period of German history. Until the late 1950s he was seen as an important figure in German history during this period. For many years after that, the dominant view was that he had little or no influence on German policy. This has been challenged since the late 1970s, particularly by Professor John C. G. Röhl, who saw Wilhelm II as the key figure in understanding the recklessness and subsequent downfall of Imperial Germany.[14]

The Great War

It is difficult to argue that Wilhelm actively sought to unleash the First World War. Though he had ambitions for the German Empire to be a world power, it was never Wilhelm's intention to conjure a large-scale conflict to achieve such ends. As soon as his better judgment dictated that a world war was imminent, he made strenuous efforts to preserve the peace—such as The Willy-Nicky Correspondence mentioned earlier, and his optimistic interpretation of the Austro-Hungarian ultimatum that Austro-Hungarian troops should go no further than Belgrade, thus limiting the conflict. But by then it was far too late, for the eager military officials of Germany and the German Foreign Office were successful in persuading him to sign the mobilization order and initiate the Schlieffen Plan. The contemporary British reference to the First World War as "the Kaiser's War" in the same way that the Second was "Hitler's War" is not wholly accurate in its suggestion that Wilhelm was deliberately responsible for unleashing the conflict. "He may not have been 'the father of war' but he was certainly its godfather' (A. Woodcock-Clarke). His own love of the culture and trappings of militarism and push to endorse the German military establishment and industry (most notably the Krupp corporation), which were the key support which enabled his dynasty to rule helped push his empire into an armaments race with competing European powers. Similarly, though on signing the mobilization order, William is reported as having said "You will regret this, gentlemen,"[15] he had encouraged Austria to pursue a hard line with Serbia, was an enthusiastic supporter of the subsequent German actions during the war and reveled in the title of "Supreme War Lord."

The Shadow-Kaiser

The role of ultimate arbiter of wartime national affairs proved too heavy a burden for Wilhelm to sustain. As the war progressed, his influence receded and inevitably his lack of ability in military matters led to an ever-increasing reliance upon his generals, so much that after 1916 the Empire had effectively become a military dictatorship under the control of Paul von Hindenburg and Erich Ludendorff. Increasingly cut-off from reality and the political decision-making process, Wilhelm vacillated between defeatism and dreams of victory, depending upon the fortunes of "his" armies. He remained a useful figurehead, and he toured the lines and munitions plants, awarded medals and gave encouraging speeches.

Nevertheless, Wilhelm still retained the ultimate authority in matters of political appointment, and it was only after his consent had been gained that major changes to the high command could be effected. William was in favor of the dismissal of Helmuth von Moltke the Younger in September 1914 and his replacement by Erich von Falkenhayn. Similarly, Wilhelm was instrumental in the policy of inactivity adopted by the High Seas Fleet after the Battle of Jutland in 1916. Likewise, it was largely owing to his sense of grievance at having been pushed into the shadows that Wilhelm attempted to take a leading role in the crisis of 1918. At least in the end he realized the necessity of capitulation and did not insist that the German nation should bleed to death for a dying cause. Upon hearing that his cousin George V had changed the name of the British royal house to Windsor, Wilhelm remarked that he planned to see Shakespeare's play The Merry Wives of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha.[16]

Attempt to use Lenin

Following the 1917 February Revolution in Russia which saw the overthrow of Great War adversary Emperor Nicholas II, Wilhelm arranged for the exiled Russian Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin to return home from Switzerland via Germany, Sweden and Finland. Wilhelm hoped that Lenin would create political unrest back in Russia, which would help to end the war on the Eastern front, allowing Germany to concentrate on defeating the Western allies. The Swiss communist Fritz Platten managed to negotiate with the German government for Lenin and his company to travel through Germany by rail, on the so-called "sealed train." Lenin arrived in Petrograd on April 16, 1917, and seized power seven months later in the October Revolution. Wilhelm's strategy paid off when the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was signed on March 3, 1918, marking the end of hostilities with Russia. On Lenin's orders, Nicholas II, William's first cousin Empress Alexandra, their five children, and their few servants were executed by firing squad in Yekaterinburg on July 17, 1918.

Abdication and flight

Wilhelm was at the Imperial Army headquarters in Spa, Belgium, when the uprisings in Berlin and other centers took him by surprise in late 1918. Mutiny among the ranks of his beloved Kaiserliche Marine, the imperial navy, profoundly shocked him. After the outbreak of the German Revolution, Wilhelm could not make up his mind whether or not to abdicate. Up to that point, he was confident that even if he were obliged to vacate the German throne, he would still retain the Prussian kingship. The unreality of this claim was revealed when, for the sake of preserving some form of government in the face of anarchy, Wilhelm's abdication both as German Emperor and King of Prussia was abruptly announced by the Chancellor, Prince Max of Baden, on November 9, 1918. (Prince Max himself was forced to resign later the same day, when it became clear that only Friedrich Ebert, leader of the SPD could effectively exert control).

Wilhelm consented to the abdication only after Ludendorff's replacement, General Wilhelm Groener, had informed him that the officers and men of the army would march back in good order under Paul von Hindenburg's command, but would certainly not fight for William's throne on the home front. The monarchy's last and strongest support had been broken, and finally even Hindenburg, himself a lifelong royalist, was obliged, with some embarrassment, to advise the Emperor to give up the crown. For his act of telling Wilhelm the truth, Groener would not be forgiven by German Arch-conservatives.

The following day, the now-former German Emperor Wilhelm II crossed the border by train and went into exile in the Netherlands, which had remained neutral throughout the war. Upon the conclusion of the Treaty of Versailles in early 1919, Article 227 expressly provided for the prosecution of Wilhelm "for a supreme offence against international morality and the sanctity of treaties," but Queen Wilhelmina refused to extradite him, despite appeals from the Allies. The erstwhile Emperor first settled in Amerongen, and then subsequently purchased a small castle in the municipality of Doorn on August 16, 1919 and moved in May 15, 1920, which was to be his home for the remainder of his life. From this residence, Huis Doorn, Wilhelm absolved his officers and servants of their oath of loyalty to him; however he himself never formally relinquished his titles, and hoped to return to Germany in the future. The Weimar Republic allowed Wilhelm to remove 23 railway wagons of furniture, 27 containing packages of all sorts, one bearing a car and another a boat, from the New Palace at Potsdam.

October 1918 Telegrams

The telegrams that were exchanged between the General Headquarters of the Imperial High Command, Berlin, and President Woodrow Wilson are discussed in Czernin's Versailles, 1919 (1964).

The following telegram was sent through the Swiss government and arrived in Washington, D.C., on 5 October 1918:[17]

- "The German Government requests the President of the United States of America to take steps for the restoration of peace, to notify all belligerents of this request, and to invite them to delegate positions for the purpose of taking up negotiations. The German Government accepts, as a basis of peace negotiations, the Program laid down by the President of the United States in his message to Congress of 8 January 1918, and his subsequent pronouncements, particularly in his address of 27 September 1918.

- In order to avoid further bloodshed the German Government requests to bring about the immediate conclusion of an armistice on land, on water, and in the air.

- Max, Prince of Baden, Imperial Chancellor"

In the subsequent two exchanges, Wilson's allusions "failed to convey the idea that the Kaiser's abdication was an essential condition for peace. The leading statesmen of the Reich were not yet ready to contemplate such a monstrous possibility." [18]

The third German telegram was sent on October 20. Wilson's reply on October 23 contained the following:

- "If the Government of the United States must deal with the military masters and the monarchical autocrats of Germany now, or if it is likely to have to deal with them later in regard to the international obligations of the German Empire, it must demand not peace negotiations but surrender. Nothing can be gained by leaving this essential thing unsaid."[19]

According to Czernin:

- "... Prince Hohenlohe, serving as councilor in the German Legation in Berne, Switzerland, cabled the German Foreign Office that 'a confidential informant has informed me that the conclusion of the Wilson note of 23 October refers to nothing less than the abdication of the Kaiser as the only way to a peace which is more or less tolerable."[20]

The abdication of Wilhelm was necessitated by the popular perceptions that had been created by the Entente propaganda against him, which had been picked and further refined when the United States declared war in April 1917.

A much bigger obstacle, which contributed to the five-week delay in the signing of the armistice and to the resulting social deterioration in Europe, was the fact that the Entente Powers had no desire to accept the Fourteen Points and Wilson's subsequent promises. As Czernin points out

- "The Allied statesmen were faced with a problem: so far they had considered the 'fourteen commandments' as a piece of clever and effective American propaganda, designed primarily to undermine the fighting spirit of the Central Powers, and to bolster the morale of the lesser Allies. Now, suddenly, the whole peace structure was supposed to be built up on that set of 'vague principles', most of which seemed to them thoroughly unrealistic, and some of which, if they were to be seriously applied, were simply unacceptable."[21]

Life in exile

On December 2, 1919, Wilhelm wrote to General August von Mackensen denouncing his abdication as the "deepest, most disgusting shame ever perpetrated by a people in history, the Germans have done to themselves," "egged on and misled by the tribe of Juda…. Let no German ever forget this, nor rest until these parasites have been destroyed and exterminated from German soil!"[22] He advocated a "regular international all-worlds pogrom à la Russe" as "the best cure" and further believed that Jews were a "nuisance that humanity must get rid of some way or other. I believe the best would be gas!"[22]

In 1922 Wilhelm published the first volume of his memoirs—a disappointingly slim volume which nevertheless revealed the possession of a remarkable memory (Wilhelm had no archive on which to draw). In them, he asserted his claim that he was not guilty of initiating the Great War, and defended his conduct throughout his reign, especially in matters of foreign policy. For the remaining 20 years of his life, the aging Emperor regularly entertained guests (often of some standing) and kept himself updated on events in Europe. Much of his time was spent chopping wood (a hobby he discovered upon his arrival at Doorn) and observing the life of a country gentleman.[23] It would seem that his attitude towards Britain and the British finally coalesced in this period into a warm desire to ape British custom. On his arrival from Germany at Amerongen Castle in the Netherlands in 1918, the first thing Wilhelm said to his host was, "So what do you say, now give me a nice cup of hot, good, real English tea."[24] No longer able to call upon the services of a court barber, and partly out of a desire to disguise his features, Wilhelm grew a beard and allowed his famous moustache to droop. Wilhelm even learned the Dutch language.

Wilhelm developed a penchant for archaeology during his vacations on Corfu, a passion he harbored into his exile. He had bought the former Greek residence of Austrian Empress Elisabeth after her murder in 1898. He also sketched plans for grand buildings and battleships when he was bored, although experts in construction saw his ideas as grandiose and unworkable. One of Wilhelm's greatest passions was hunting, and he bagged thousands of animals, both beast and bird. During his years in Doorn, he largely deforested his estate, the land only now beginning to recover.

In the early 1930s, Wilhelm apparently hoped that the successes of the German Nazi Party would stimulate interest in the revival of the monarchy. His second wife, Hermine (see below), actively petitioned the Nazi government on her husband's behalf, but the scorn which Adolf Hitler felt for the man whom he believed contributed to Germany's greatest defeat, and his own desire for power would prevent Wilhelm's restoration. Though he hosted Hermann Göring at Doorn on at least one occasion, Wilhelm grew to mistrust Hitler. He heard about the Night of the Long Knives of 30 June 1934 by wireless and said of it, "What would people have said if I had done such a thing?"[25] and hearing of the murder of the wife of former Chancellor Schleicher, "We have ceased to live under the rule of law and everyone must be prepared for the possibility that the Nazis will push their way in and put them up against the wall!"[26] Wilhelm was also appalled at the Kristallnacht of 9-10 November 1938 saying, "I have just made my views clear to Auwi [Wilhelm's fourth son] in the presence of his brothers. He had the nerve to say that he agreed with the Jewish pogroms and understood why they had come about. When I told him that any decent man would describe these actions as gangsterisms, he appeared totally indifferent. He is completely lost to our family ..."[27]

In the wake of the German victory over Poland in September 1939, Wilhelm's adjutant, General von Dommes, wrote on his behalf to Hitler, stating that the House of Hohenzollern "remained loyal" and noted that nine Prussian Princes (one son and eight grandchildren) were stationed at the front, concluding "because of the special circumstances that require residence in a neutral foreign country, His Majesty must personally decline to make the aforementioned comment. The Emperor has therefore charged me with making a communication." William stayed in regular contact with Hitler through General von Dommes, who represented the family in Germany.[28] William greatly admired the success which Hitler was able to achieve in the opening months of the Second World War, and personally sent a congratulatory telegram on the fall of Paris stating "Congratulations, you have won using my troops." Nevertheless, after the Nazi conquest of the Netherlands in 1940, the aging Wilhelm retired completely from public life.

During his last year at Doorn, Wilhelm believed that Germany was the land of monarchy and therefore of Christ and that England was the land of Liberalism and therefore of Satan and the Anti-Christ. He argued that the English ruling classes were "Freemasons thoroughly infected by Juda." Wilhelm asserted that the "British people must be liberated from Antichrist Juda. We must drive Juda out of England just as he has been chased out of the Continent."[29] He believed the Freemasons and Jews had caused the two world wars, aiming at a world Jewish empire with British and American gold, but that "Juda's plan has been smashed to pieces and they themselves swept out of the European Continent!" Continental Europe was now, Wilhelm wrote, "consolidating and closing itself off from British influences after the elimination of the British and the Jews!" The end result would be a "U.S. of Europe!"[29] In a letter to his sister Princess Margaret in 1940, Wilhelm wrote: "The hand of God is creating a new world & working miracles.... We are becoming the U.S. of Europe under German leadership, a united European Continent." He added: "The Jews [are] being thrust out of their nefarious positions in all countries, whom they have driven to hostility for centuries."[28] Also in 1940 came what would have been his mother's 100th birthday, of which he ironically wrote to a friend "Today the 100th birthday of my mother! No notice is taken of it at home! No 'Memorial Service' or... committee to remember her marvelous work for the...welfare of our German people...Nobody of the new generation knows anything about her." [30]

The entry of the German army into Paris stirred painful, deep-seated emotions within him. In a letter to his daughter Victoria Louise, the Duchess of Brunswick, he wrote:

- "Thus is the pernicious entente cordial of Uncle Edward VII brought to naught."[31]

Concerning Hitler's persecutions of the Jews:

- "The Jewish persecutions of 1938 horrified the exile. 'For the first time, I am ashamed to be a German.'"[32]

Death

Wilhelm II died of a pulmonary embolus in Doorn, the Netherlands on June 4, 1941 aged 82, with German soldiers at the gates of his estate. Hitler, however, was reportedly angry that the former monarch had an honor guard of German troops and nearly fired the general who ordered them there when he found out. Despite his personal animosity toward Wilhelm, Hitler nonetheless hoped to bring Wilhelm's body back to Berlin for a State funeral for propaganda purposes, as Wilhelm was a symbol of Germany and Germans during World War I. (Hitler felt this would demonstrate to Germans the direct succession of the Third Reich from the old Kaiserreich.)[33] However, Wilhelm's wishes of never returning to Germany until the restoration of the monarchy were nevertheless respected, and the Nazi occupation authorities granted a small military funeral with a few-hundred people present, the mourners at which included the hero of the First World War August von Mackensen, along with a few other military advisers. Wilhelm's request that the swastika and other Nazi regalia not be displayed at the final rites was ignored, however, and they feature in the photos of the funeral that were taken by a Dutch photographer. [34]

He was buried in a mausoleum in the grounds of Huis Doorn, which has since become a place of pilgrimage for German monarchists. To this day, small but enthusiastic numbers of German monarchists gather at Huis Doorn every year on the anniversary of his death to pay their homage to the last German Emperor.

First marriage and issue

Wilhelm and his first wife, Princess Augusta Viktoria of Schleswig-Holstein, were married on February 27, 1881. They had seven children:

- Crown Prince Wilhelm (1882–1951) married Duchess Cecilie of Mecklenburg-Schwerin (September 20, 1886 - May 6, 1954) in Berlin on June 6, 1905. Cecilie was the daughter of Grand Duke Frederick Francis III of Mecklenburg-Schwerin (1851-1897) and his wife, Grand Duchess Anastasia Mikhailovna of Russia (1860-1922). They had six children. Ironically his eldest son was killed in 1940 in World War II-as a result of political decisions by his own father and grandfather.

- Prince Eitel Friedrich (1883–1942). On February 27, 1906 Prince Eitel married Duchess Sophie Charlotte Holstein-Gottorp of Oldenburg (February 2, 1879 Oldenburg, Germany - March 29, 1964 Westerstede, Germany) in Berlin, Germany. They were divorced 20 October 1926 and had no children.

- Prince Adalbert (1884–1948). He married Princess Adelheid "Adi" Arna Karoline Marie Elisabeth of Saxe-Meiningen (August 16, 1891- April 25, 1971) on August 3, 1914 in Wilhelmshaven, Germany. They had three children.

- Prince August Wilhelm (1887–1949). He married Princess Alexandra Victoria of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg (April 21, 1887 Germany - April 15, 1957 France), on October 22, 1908. They had one child.

- Prince Oskar (1888–1958). He was married on July 31, 1914 to Countess Ina-Marie Helene Adele Elise von Bassewitz (January 27, 1888 - September 17, 1973). This marriage was morganatic, and so upon marriage Ina-Marie was created Countess von Ruppin. In 1920, she and her children were granted the rank of Prince/ss of Prussia with the style Royal Highness. They had four children. His eldest son was killed in 1939 in World War II—like his cousin—as a result of political decisions by his uncle and grandfather.

- Prince Joachim (1890–1920) married Princess Marie-Auguste of Anhalt (June 1898 – May 22, 1983), on March 11, 1916. The couple had one son. Joachim's great grandson Grand Duke George Mikhailovich of Russia, Prince of Prussia (born 1981) is a claimant to the Russian throne.

- Princess Viktoria Luise (1892–1980); married 1913 to Ernest Augustus, Duke of Brunswick {1887-1953}. Victoria Louise and Ernest Augustus had five children.

Augusta, known affectionately as "Dona," was a close and constant companion to Wilhelm throughout his life, and her death on April 11, 1921 was a devastating blow. It also came less than a year after their son, Joachim, had committed suicide, unable to accept his lot after the abdication of his father, the failure of his own marriage to Princess Marie-Auguste of Anhalt, and the heavy depression felt after his service in the Great War.

Remarriage

The following January, Wilhelm received a birthday greeting from a son of the deceased Prince Johann George Ludwig Ferdinand August Wilhelm of Schönaich-Carolath (September 11, 1873 – April 7, 1920). The 63-year-old William invited the boy and his widowed mother, Princess Hermine Reuss (December 17, 1887 – August 7, 1947), to Doorn. Princess Hermine was the daughter of Prince Henry XXII Reuss. Wilhelm found her very attractive, and greatly enjoyed her company. By early 1922, he was determined to marry the 34-year-old mother of five, and the couple was eventually wed on November 9, 1922, despite grumblings from Wilhelm's monarchist supporters and the objections of his children. Hermine's daughter, Henriette, eventually married Wilhelm's grandson, Prince Joachim's son, Karl Franz Josef, (Wilhelm's stepdaughter and grandson respectively). Hermine remained a constant companion to the aging Emperor until his death.

Alleged extramarital affairs

Wilhelm was implicated in some 30 degrees in the scandal over his aide and great friend, Philipp, Prince of Eulenburg-Hertefeld, which revealed homosexual activities (then illegal under German law) within Wilhelm's inner circle (the Harden-Eulenburg Affair). Bismarck, among others, suggested that there was an inappropriate relationship between Wilhelm and Eulenburg. There is no conclusive evidence to prove that the Emperor and Eulenburg's relationship went beyond friendship, but there was suspicion that he was homosexual.

Legacy

Wilhem did not leave behind the legacy he would have wished for. He wanted Germany to march across the stage of history as a world power with an empire to compete with or to excel those of Europe's other imperial powers. His militancy contributed led to World War I. On the one hand, he was surrounded by advisers who favored war; on the other hand, "the First World War did not have to come." Röhl argues that public opinion in Germany did not support war but that those who had the power to take decisions were not bound by public opinion, pointing out that the government did not depend "on the will of a majority in the Reichstag." Röhl says that if Germany had developed a constitutional monarchy with "a collective cabinet responsible to parliament" the war would not have happened.[35] At a time when other European monarchies were becoming or had become constitutional monarchies, Wilhelm was exercising

As King of Prussia, Wilhelm possessed and exercised absolute power in military matters; he set up a system in which he also exercised ultimate decision-making power in domestic matters too.[36] It was, says Röhl the Kaiser and his "court, rather than the Chancellor and his 'men" who exercised political power and decision-making" from the 1890s on. Germany's enemies in World War I thought that by winning the war they would end all war, then use the opportunity to build a new world order in which non-violent resolution of disputes would replace armed conflict. However, they punished Germany with such heavy war reparations and other measures that their own victory became one of the causes of another World War. Wilhelm had presided over what has been called less a state with an army than an army with a state;[37] war for such a state is very tempting. In the period between the two world wars, Germany under Adolf Hitler began to rearm on an massive scale, again becoming an army with a state, making war almost inevitable. Germany's weak democratic tradition, which owes much to the Kaiser's rule, was also a factor in Hitler's rise to power; he became Chancellor despite having only achieved 37 percent of the popular vote in any "honest elections."[38] The ultimate lesson that Wilhelm II's life teaches humanity is that countries that equip for war end up at war, while countries that make trade, not military capability, their priority value peace and work to make peace a permanent reality. In the post World War II space, Germany joined with its former foes to make war "unthinkable and materially impossible"[39] with Germany's own Chancellor, Konrad Adenauer, among the pioneers and leaders of what has been called the new Europe.

Ancestry

Patrilineal descent

Wilhelm's patriline is the line from which he is descended father to son.

Patrilineal descent is the principle behind membership in royal houses, as it can be traced back through the generations—which means that if Wilhelm II were to have chosen a historically accurate house name it would have been House of Hohenzollern, as all his male-line ancestors were of that house.

House of Hohenzollern

- Burkhard, Count of Zollern

- Frederick I, Count of Zollern, d. 1125

- Frederick II of Zollern and Hohenberg, d. 1145

- Frederick I, Burgrave of Nuremberg, 1139–1200

- Conrad I, Burgrave of Nuremberg, 1186–1261

- Frederick III, Burgrave of Nuremberg, 1220–1297

- Frederick IV, Burgrave of Nuremberg, 1287–1332

- John II, Burgrave of Nuremberg, 1309–1357

- Frederick V, Burgrave of Nuremberg, 1333–1398

- Frederick I, Elector of Brandenburg, 1371–1440

- Albert III Achilles, Elector of Brandenburg, 1414–1486

- John Cicero, Elector of Brandenburg, 1455–1499

- Joachim I Nestor, Elector of Brandenburg, 1484–1535

- Joachim II Hector, Elector of Brandenburg, 1505–1571

- John George, Elector of Brandenburg, 1525–1598

- Joachim Frederick, Elector of Brandenburg, 1546–1608

- John Sigismund, Elector of Brandenburg, 1572–1619

- George William, Elector of Brandenburg, 1595–1640

- Frederick William, Elector of Brandenburg, 1620–1688

- Frederick I of Prussia, 1657–1713

- Frederick William I of Prussia, 1688–1740

- Prince Augustus William of Prussia, 1722–1758

- Frederick William II of Prussia, 1744–1797

- Frederick William III of Prussia, 1770–1840

- Wilhelm I, German Emperor, 1797–1888

- Frederick III, German Emperor, 1831–1888

- Wilhelm II, German Emperor, 1859–1941

Titles and styles

- January 27, 1859 - March 9, 1888: His Royal Highness Prince Wilhelm of Prussia

- March 9, 1888 - June 15, 1888: His Imperial and Royal Highness The German Crown Prince, Crown Prince of Prussia

- June 15, 1888 – June 4, 1941: His Imperial and Royal Majesty The German Emperor, King of Prussia

Full title as German Emperor

His Imperial and Royal Majesty Wilhelm the Second, by the Grace of God, German Emperor and King of Prussia, Margrave of Brandenburg, Burgrave of Nuremberg, Count of Hohenzollern, Duke of Silesia and of the County of Glatz, Grand Duke of the Lower Rhine and of Posen, Duke of Saxony, of Angria, of Westphalia, of Pomerania and of Lunenburg, Duke of Schleswig, of Holstein and of Crossen, Duke of Magdeburg, of Bremen, of Guelderland and of Jülich, Cleves and Berg, Duke of the Wends and the Kashubians, of Lauenburg and of Mecklenburg, Landgrave of Hesse and in Thuringia, Margrave of Upper and Lower Lusatia, Prince of Orange, of Rugen, of East Friesland, of Paderborn and of Pyrmont, Prince of Halberstadt, of Münster, of Minden, of Osnabrück, of Hildesheim, of Verden, of Kammin, of Fulda, of Nassau and of Moers, Princely Count of Henneberg, Count of the Mark, of Ravensberg, of Hohenstein, of Tecklenburg and of Lingen, Count of Mansfeld, of Sigmaringen and of Veringen, Lord of Frankfurt. [40]

Ancestors

| Ancestors of Wilhelm II, German Emperor | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

- ↑ Balfour 1964, 132.

- ↑ Kohut 1991, 194.

- ↑ Balfour 1964, 226–227

- ↑ Palmer 1978, 267.

- ↑ Taylor. 1963, 264.

- ↑ Winston Churchill, and Harry V. Jaffa, 1981, Statesmanship: essays in honor of Sir Winston Spencer Churchill. Studies in statesmanship of the Winston S. Churchill Association. Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press. ISBN 9780890891650. 119. attributed to Bismarck by Albert Ballin.

- ↑ Ludwig and Mayne 1927, 73.

- ↑ Giles St. Aubyn, 1992, Queen Victoria: a portrait. New York, NY: Atheneum. ISBN 9780689121418. 598.

- ↑ The interview of the Emperor Wilhelm II on 28 October 1908 (excerpt). London Daily Telegraph, World War I Archive. Retrieved December 20, 2008.

- ↑ The Opening of the Kiel Canal. Screenonline. Retrieved December 20, 2008.

- ↑ Ludwig and Mayne 1927, 444.

- ↑ Balfour 1964, 350–51.

- ↑ Ludwig and Mayne 1927, 453.

- ↑ Röhl 1994, 10.

- ↑ Taylor 1963, 228.

- ↑ MacDonogh 2001, 392.

- ↑ Czernin 1964, 6.

- ↑ Czernin 1964, 7.

- ↑ Ludwig and Mayne 1927, 489.

- ↑ Czernin 1964, 9.

- ↑ Czernin 1964, 23.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Röhl 1994, 210.

- ↑ MacDonogh 2001, 457.

- ↑ MacDonogh 2001, 419.

- ↑ MacDonogh 2001, 452.

- ↑ MacDonogh 2001, 452–452.

- ↑ MacDonogh 2001, 456.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Petropoulos 2006, 170.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Röhl 1996, 211.

- ↑ Pakula 1995, 602.

- ↑ Palmer 1978, 226.

- ↑ Balfour 1964, 419.

- ↑ Jack Sweetman, 1973, The Unforgotten Crowns: The German Monarchist Movements, 1918-1945. Emory University dissertation. 654–655.

- ↑ Sweetman 1973, 459.

- ↑ Röhl 1996, 8.

- ↑ Röhl 1996, 4.

- ↑ William L. Shirer, 1990, The rise and fall of the Third Reich. (New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9780671728694), 93.

- ↑ Steve Kangas (ed.), Myth: Democracy elected Hitler to power. huppi.com. Retrieved December 20, 2008.

- ↑ Declaration of May 9. Europe Day. Retrieved December 20, 2008.

- ↑ Titles and styles of William II. web.archive.org. Retrieved December 20, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Balfour, Michael. 1964. The Kaiser and His Times. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin. ISBN 9780140217964.

- Benson, E.F. 1936. The Kaiser and English Relations. London, UK: Longmans, Green.

- Cecil, Lamar. 1989. Wilhelm II: Prince and Emperor, 1859-1900. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9780807818282

- Cecil, Lamar. 1996. Wilhelm II: Emperor and Exile, 1900-1941. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9780807818282.

- Czernin, Ferdinand. 1964. Versailles, 1919: the forces, events, and personalities that shaped the treaty. New York, UK: Putnam.

- Hull, Isabel V. 1982. The Entourage of Kaiser Wilhelm II, 1888-1918. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521236652.

- Kohut, Thomas A. 1991. Wilhelm II and the Germans: A Study in Leadership. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195061727.

- Ludwig, Emil, and Ethel Colburn Mayne. 1927. Wilhelm Hohenzollern, the last of the Kaisers. Whitefish, MT: Kessinger. ISBN 0766143414.

- MacDonogh, Giles. 2001. The Last Kaiser: William the Impetuous. London, UK: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 9780297817765.

- Mombauer, Annika and Wilhelm Deist (eds.). 2003. The Kaiser: New Research on Wilhelm II's Role in Imperial Germany. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780511062186.

- Pakula, Hannah. 1995. An uncommon woman: the Empress Frederick, daughter of Queen Victoria, wife of the Crown Prince of Prussia, mother of Kaiser Wilhelm. New York, UK: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9780684808185.

- Palmer, Alan. 1978. The Kaiser: Warlord of the Second Reich. London, UK: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 9780684156378.

- Petropoulos, Jonathan. 2006. Royals and the Reich: the princes von Hessen in Nazi Germany. New York, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195161335.

- Retallack, James. 1996. Germany in the Age of Kaiser Wilhelm II. Basingstoke, UK: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 9780312160319.

- Röhl, John C.G. 1996. The Kaiser and his court: Wilhelm II and the government of Germany. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521565042.

- Röhl, John C.G. 1998. Young Wilhelm: The Kaiser's Early Life, 1859-1888. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521497527. (Volume I of Röhl's massive new biography).

- Röhl, John C.G. 2004. The Kaiser's Personal Monarchy, 1888-1900. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521819206. (Volume II of Röhl's massive new biography).

- Röhl, John C.G. and Nicholaus Sombart eds. 2005. Kaiser Wilhelm II: New Interpretations _ the Corfu Papers. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521019903.

- Taylor, Edmond. 1963. The fall of the dynasties; the collapse of the old order, 1905-1922. Garden City, NY: Doubleday.

- Taylor, Alan John Percivale. 1978. Bismarck: the man and the statesman. London, UK: Hamish Hamilton.

- Van der Kiste, John. 1999. Kaiser Wilhelm II: Germany's last emperor. Stroud, UK: Sutton. ISBN 9780750927369.

- Whittle, Tyler. 1977. The Last Kaiser: A Biography of William II, Emperor of Germany and King of Prussia. London, UK: Heinemann. ISBN 9780812907162.

External links

All links retrieved May 5, 2023.

- The German Emperor as shown in his public utterances.

- My Memoirs: 1878-1918 by William II, London: Cassell & Co., 1922.

- The German emperor's speeches: being a selection from the speeches, edicts, letters, and telegrams of the Emperor William II.

- Wilhelm II (WWI Biographical Dictionary).

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.