| Books of the |

The Book of Numbers is the fourth of the books of the Pentateuch, included in both Jewish and Christian scriptures. It continues the story of the Israelites' journey toward Canaan, which was begun in the Book of Exodus. Its name comes from the the Septuagint Greek version of the Hebrew Bible in which it is called Arithmoi ("Numbers") because it begins with the numbering of the people at Sinai (Chapters 1-4) and later tells of a census on the plain of Moab (Chapter 26). In the Hebrew version it is titled Ba-Midbar (במדבר) ("In the Desert") a name taken from its opening lines.

The main theme running through the Book of Numbers is the people's lack of faith as they confront the harsh trials of wilderness life. Time and again they complain and murmur as they wander through the wilderness, disbelieving in Moses and despairing of ever reaching the land of Canaan. In incident after incident the faithless and rebels are weeded out, leaving only a faithful remnant—the second generation—to enter the Promised Land. The book contains several of the Bible's most memorable episodes:

- The story of the Israelite spies in Canaan.

- God's decision to have the Israelites wander for 40 years in the wilderness.

- The rebellion of Korah and his followers against Aaron's priesthood.

- The story of Aaron's rod that budded.

- Moses' sin of striking the rock at Kadesh.

- The construction of the bronze serpent that healed the Israelites.

- The deaths of Miriam and Aaron.

- The episode of the Moabite prophet Balaam and his talking donkey.

- The seduction of the Israelites into sexual and religious sin at Baal Peor.

- The conquest of Moabite and Midianite lands east of the Jordan.

It also provides details as to the route of the Israelites in the wilderness and their principal encampments, as well as a number of laws governing the conduct of sacrifices, procedures for criminal offensives, and the proper conduct of holy war.

Summary

Overview

Numbers takes up the story that ended in Exodus with the successful construction of the Tabernacle. The Book of Leviticus provides a lengthy interlude between the two narratives, dealing primarily with religious regulations. After a tragic false start due to the episode of the Golden Calf, the Israelites are now strongly united, with Moses and Aaron as their leaders and the Tabernacle as their sacred sanctuary. God is visibly present with them, showing them when to camp by settling in a cloud over the Tabernacle and signaling when to leave by causing the cloud to rise. A short journey is initially envisioned as the Israelites march north toward Canaan.

The book goes on to describe their initial faith, their subsequent complaints about the gift of manna, their failure to act with confidence after hearing the reports of spies sent to survey the land of Canaan, and their consequent 40 years of dreary wandering when God determines to punish the first generation of Israelites for their faithlessness by having them gradually die in the wilderness. By the book's end, all of those who were adults at the time of the initial Exodus except Moses, Joshua, and Caleb, have perished. The new generation, though far from perfect spiritually, demonstrates substantial military strength, and the Israelites are finally poised for conquest.

Numbering the tribes

The book opens as God orders Moses, in the wilderness of Sinai, to take the number of those able to bear arms among the men "from 20 years old and upward"—the tribe of Levi being excepted—and to appoint chiefs over each tribe. The result of the numbering is that 603,550 Israelites are found to be fit for military service. The Levites are assigned exclusively the service of the Tabernacle (Chapter 1). The Levites are to camp immediately outside of the Tabernacle, with the other tribes encamped around the Levites, each tribe being distinguished by its chosen banner. Judah, Issachar, and Zebulen encamp to the east of the Tabernacle; Reuben, Simeon, and Gad to the south; Ephraim and Manasseh to the west; and Dan, Asher, and Naphtali to the north. The same order is to be preserved for the march. (Chapter 2)

Priests, Levites and laws

Because of the death of Aaron's sons Nadab and Abihu, only his remaining sons Eleazar and Ithamar serve as priests during his lifetime.[1] The Levites are formally ordained, taking the place of the first-born Israelite, who were hitherto claimed by God as his.

The Levites are also divided into three families, the Gershonites, the Kohathites, and the Merarites, each under a chief, and all headed by a supreme leader, Eleazar, the son of Aaron. The death penalty is stipulated for any unauthorized person approaching the sanctuary, and a redemption fee is instituted for first-born Israelites who would otherwise have to serve at the Tabernacle (Chapter 3). Each of the three branches of Levites from 30 to 50 years of age is numbered, and their special duties are defined. The total number of Levites eligible to serve comes to 8,580 (Chapter 4).

People with certain skin diseases and other ritually unclean persons are excluded from the camp. Restitution must be made for wrongs committed against another person. Also: "Each man's sacred gifts are his own, but what he gives to the priest will belong to the priest."

If a man suspects his wife of infidelity, he is to bring her to the priest with an offering. The priest will then perform a ritual in which the woman swears an oath and drinks "bitter water." She will suffer a horrible curse if her oath is false (Chapter 5).[2]

Ordinances are instituted concerning the taking of the vow of a Nazirite.[3] The famous priestly blessing is formally pronounced:

- The Lord bless you and keep you;

- the Lord make his face shine upon you and be gracious to you;

- the Lord turn his face toward you and give you peace. (Num. 6:24-27)

The Tabernacle is finished, and each of the chiefs of the 12 tribes brings a rich offering. The golden Menorah is lit, and the Levites are formally consecrated to begin their duties. The retirement age for Levites is set at 50 years. The Passover holiday is instituted and celebrated. The penalty for not celebrating Passover is to be "cut off." Aliens are permitted to celebrate Passover under the same regulations as Israelites.

The Israelites prepare to continue on their journey. The will camp when the holy cloud of God settles over the Tabernacle, and move on when the cloud lifts (Chapters 7-9).

Moses makes two silver trumpets for convoking the congregation and announcing the recommencement of a journey, and the various occasions for the use of the trumpets are stipulated.

The Israelites begin their first journey after the construction of the Tabernacle, stopping at the Desert of Paran. Moses invites his brother-in-law, Hobab the Midianite to join them. He declines at first, but agrees after Moses implores him to act as their guide through the desert (Chapter 10).

Complaints bring God's anger

At Taberah, God becomes angry upon hearing the complaints of the people and sends fire to consume some of those on the outskirts of the camp. The continued grumbling of the people over the monotony of having to eat only manna, causes Moses to lose patience. He complains to God that his burden of leadership is too heavy. God tells him to choose 70 elders to assist him in the government of the people. God also promises quail for the people to eat. The 70 elders are brought close to the sacred tent. They are touched by the Spirit that was formerly only with Moses, and immediately prophesy. At Kibroth Hattaavah, God provides abundant quail as promised, but smites the people with a plague for having complained about his earlier gift of manna (Chapter 11).

At Hazeroth, Miriam and Aaron criticize Moses for having married a Chushite woman, claiming that they, too, are prophets. God calls them to the sacred tent and explains that, while Moses' siblings indeed are prophets, Moses' authority is not to be challenged, because he speaks with God "face to face." Miriam is punished with a skin disease and is shut out of camp for seven days, at the end of which the Israelites proceed again to the wilderness of Paran (Chapter 12).

Spying in Canaan

God commands Moses to send spies into Canaan, one leader from each of the tribes. After 40 days, the spies return and report to Moses, Aaron, and to the whole assembly at Kadesh in the wilderness of Paran. They report the land to be rich and "flowing with milk and honey." However, they also bring intelligence that the towns are walled and heavily fortified. Caleb urges an aggressive course, confident that the land can be taken. The other spies, however, counsel caution, spreading a "bad report" about giant Nephilim and other formidable foes that inhabit the land (Chapter 13).

That night, treason against Moses and Aaron spreads in the camp, and there is talk of electing a new leader who will lead the Israelites back to Egypt. Joshua and Caleb remain loyal, imploring the people to have faith that God will deliver victory to them. Their speeches, however, are to no avail. God again becomes angry and tells Moses that he plans to kill all of the Israelites and begin a new nation descended from Moses. Arguing that the Egyptians and Canaanites will think that Yahweh is powerless to fulfill his promises and will think badly of him, Moses convinces God to relent. God is apparently moved by Moses' entreaties and agrees to forgive. However, his mercy is limited, as he tells Moses and Aaron that he will cause all of the generation who witnessed the early miracles of the Exodus to die in the wilderness, the two exceptions being Joshua and Caleb alone.

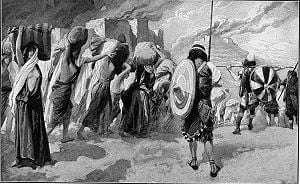

God sentences the Israelites to 40 years of wandering, one year for each day of spying. The fickle Israelites quickly repent and determine to march immediately into Canaan. Moses forbids this and refuses either to join them or to allow the Ark of the Covenant to serve as their standard. Without divine support, the army is badly beaten by a coalition force of Canaanites and Amalekites, and the Israelites are forced to retreat to Hormah (Chapter 14).

God reveals various ordinances regarding future life in Canaan. Non-Israelites are allowed to participate in the sacrificial worship of Yahweh, but are required to follow the same standards as Israelites. Sin offerings are provided for the atonement of those who sin unintentionally. But those who sin willfully are guilty of blasphemy and must be "cut off." An immediate demonstration is provided as a man is caught carrying wood on the sabbath. God commands Moses to have him stoned to death, and the man is taken outside the camp and executed for his crime (Chapter 15).

Korah's rebellion

Korah, a grandson of the Levite chief Kohath, leads a movement that attempts to democratize the priesthood, claiming: "The whole community is holy, every one of them, and the Lord is with them. Why then do you set yourselves above the Lord's assembly?" Supporting him are 250 well respected members of the community. Moses challenges them to meet at the sacred altar the next morning and let God decide the matter, claiming the Korah and his followers have rebelled not against Aaron's priesthood but against God himself. Moses prays that God will not accept the offering of the would-be priests.

In the morning, God commands Moses and Aaron to have the rest of the assembly move away from the tents of Korah and his followers. The families of the rebels are promptly killed as the ground opens up to swallow them. God then sends fire to slay the usurper-priests at the altar. When some the remaining people hold Moses responsible for the slaughter, God sends a plague upon the entire camp, killing and additional 14,700 people until Aaron succeeds in placating God with an offering of incense (Chapter 16). God confirms his support of Aaron's priesthood by having Moses gather one rod from each of the tribes and miraculously causing Aaron's rod alone, representing the tribe Levi, to bloom (Chapter 17).

Aaron and his family are declared by God to be responsible for any iniquity committed in connection with the sanctuary. The Levites are again appointed to help Aaron and his sons, the priests, in the keeping of the Tabernacle. The priestly portions and tithes given to the Levites are specified. The Levites must in turn tithe to the priests (Chapter 18). Aaron's son Eleazer models a rite of purification through the sacrifice of a red heifer. Other laws of purification are also instituted (Chapter 19).

The Sin of Moses

After Miriam's death at Kadesh, the Israelites complain to Moses and Aaron because of a lack of water. Moses, ordered by God to speak to the rock, grows furious with the Israelites and disobeys God by striking the rock instead of speaking to it. Water is produced, but Moses and Aaron are punished by God's announcement that they will not be allowed to enter Canaan: "Because you did not trust in me enough to honor me as holy in the sight of the Israelites, you will not bring this community into the land I give them."

Why was it a sin when Moses struck the rock twice? Some Christians speculate that as "the Rock was Christ" (1 Cor. 10:4), when Moses struck it twice in anger he symbolically struck Christ and dishonored him, thus prefiguring the opposition Jesus would face from his own people.

As the Israelites near Canaan, the king of Edom refuses permission for them to pass through his land. Aaron dies on Mount Hor in the territory of Edom, and is succeeded as high priest by his son Eleazer[4] (Chapter 20).

The bronze serpent

King Arad of Canaan is defeated at Hormah and several Canaanite towns are utterly destroyed by the Israelites. Having been denied passage through Edom, the Israelites retrace their route from Mount Hor to the Red Sea.

On the way, they are bitten by a horde of "fiery serpents" after speaking against God and Moses. When the people repent, God commands Moses to fashion and uplift a bronze statue of a serpent, which heals any Israelite who gazes at it.[5]

Moving north toward the valley of Moab, the Israelites ask permission of Sihon, king of the Amorites, to pass through his land. When he refuses, they defeat him and take over his lands. They also conquer another Amorite king, Og of Bashan, and take control of his territories (Chapter 21).

The legend of Balaam

As the Israelites continue their conquest of Moabite towns the Moabite king Balak hires the prophet Balaam son of Beor to curse the approaching Israelite army. Balaam communicates not with a pagan god but with Yahweh himself, who commands him not to curse the Israelites, because "they are blessed." Balak sends other princes to Balaam, offering him rich bribes, but he resists on the grounds that he must not disobey "Yahweh my God."

In a humorous episode, God sends an angel to block Balaam's path as he travels to meet Balak. Balaam's donkey lays down in the road under her master, who does not see the angel. After being strongly urged to continue, the donkey—suddenly able to speak—complains, saying; "What have I done to you to make you beat me these three times?" The dialog between Balaam and his ass continues until Balaam finally notices the angel, who informs him that if were it not for donkey's reticence, Balaam would have surely been killed.

The angel repeats God's previous instructions to Balaam, who then continues his journey and meets Balak as planned. Balak prepares seven altars at Kiriath Huzoth, and he and Balaam together sacrifice a bull and a ram on each altar. God inspires Balaam with the following prophetic message:

Undeterred, Balak erects new altars on a different high place, at Pisgah, and offers new sacrifices there, but Balaam prophesies: "There is no sorcery against Jacob, no divination against Israel." Balak tries again at Peor, with similar results, as Balaam looks over the approaching Israelite horde and declares: "How beautiful are your tents, O Jacob, your dwelling places, O Israel! …May those who bless you be blessed and those who curse you be cursed!"

The disappointed Balak finally dismisses Balaam, who returns home, pronouncing a prophecy of doom against Moab as he does so.

Moabite women

Despite Balaam's declaration of God's blessing, the Israelites themselves earn God's curse. Encamped at Shittim, they commit sexual sin with the women of Moab and join them in worshiping the Baal of Peor. God commands Moses to execute all the participants in this episode. A plague destroys 24,000 Israelites until it is put to a stop when Aaron's grandson, the priest Phinehas, takes a spear and with one mighty thrust gruesomely slays both an Israelite leader and his Midianite wife, a local princess. Impressed by Phinehas' zeal, God promises his lineage "a covenant of a lasting priesthood." God commands Moses to treat the Midianites as "enemies and kill them." (Chapter 25)

A new census, taken just before the entry into the land of Canaan, gives the total number of males from 20 years and upward as 601,730. The number of the Levites from a month old and upward is 23,000. The land shall be divided by lot. The daughters of Zelophehad, their father having no sons, share in the allotment, establishing a precedent for Israelite females to inherit land. On God's orders, Moses commissions Joshua as his successor (Chapters 26-27).

Prescriptions are given for the observance of various feasts and offerings. Laws are instituted concerning the vows of men and of both married and unmarried women (Chapters 28-30).

War against Midan

God commands a war of "vengeance" against Midan. An Israelite force of 12,000 carries out the task with Phinehas as their standard-bearer. They kill "every man," of the opposition, including five Midianite kings and the unfortunate Balaam, the prophet who had previously refused to curse them at the risk of his life.

The Israelites plunder and burn the Midianite towns, taking their women and children captive. Moses scolds them for letting the women and boys live and blames Balaam for the seduction of the Israelites into Baal worship. He orders the commanders: "Now kill all the boys. And kill every woman who has slept with a man, but save for yourselves every girl who has never slept with a man." Other laws of wartime plunder are also instituted and the sizable Midianite booty is enumerated (Chapter 31).

The Reubenites and the Gadites request that Moses assign them the land east of the Jordan. After exacting their promise to join in the conquest of the land west of the Jordan before settling, Moses grants their request. The land east of the Jordan is divided among the tribes of Reuben, Gad, and the half-tribe of Manasseh. Cities are rebuilt and renamed by these tribes (Chapter 32).

The final chapters

A detailed list is given of the Israelites' stopping points during their 40 years' wanderings in the wilderness, many of which have not been previously mentioned. On in the plains of Moab the Israelites are told that, after crossing the Jordan, they should expel the Canaanites and destroy their idols.

The boundaries of the land of which the Israelites are about to take is specified. The land is to be divided among the tribes—other than Gad, Reuben, and Mannasseh—by lot. The Levites, however, are to live throughout the country in 48 specified towns.[6] They are also to receive pasture land for their flocks. Laws are instituted concerning murder, cities of refuge, and female inheritance (Chapters 33-36).

Modern Views

Modern scholars find ample evidence to suggest that the Book of Numbers was not written by Moses as tradition holds, but was compiled from several sources long after the events it describes. The book repeats itself, contradicts other parts of the the five "books of Moses," and contains several distinct, identifiable styles, which implies multiple authors with varying outlooks and interests. Only one passage—namely the section beginning with "At the Lord's command Moses recorded the stages in their journey…" (Chapter 33:2)—actually claims to have Moses as its author. But even this passage is met with skepticism and is considered to be one of the latest in the Pentateuch.

The consensus of critical scholarship holds to the view of the documentary hypothesis, namely that three primary sources—designated as "J," (Yahwist) "E," (Elohist) and "P," (Priestly)—furnished the basic material for the Book of Numbers, and also for much of the rest of the Pentateuch. The influence of the later Deuteronomist ("D") is also seen to a lesser degree as well as that of an even more recent Redactor ("R"). According to this theory, the earliest sources were written, edited, and combined in stages starting around the ninth century B.C.E., and the book did not reach its final form until at least the sixth century and possibly not until after the Babylonian exile.

The first section of the book (Chapters 1-10), covering the last several days at Sinai, comes mostly from P. Beginning with chapter 11, the sources become more complex, with J, E, and P being each represented. The hand of J is detected in the account of Moses' father-in-law being called Reuel instead of Jethro. The story of the quails, in which Yahweh behaves so mercurially, is also thought to be typical of J. On the other hand, sections of chapters 11 and 12, as evidenced by their particular descriptions of the tent of meeting lying away from the camp, are thought to be from E. The priestly source is again evident in the narratives dealing with sacrificial laws and the tradition of fringes on priestly garments, the story of the execution of the man found gathering wood on the Sabbath, the account of the budding of Aaron's rod, etc. E, which takes a dimmer view of Aaron, is thought to have supplied the story of Aaron and Miriam's criticism of Moses as well as the narrative of the origin of the brazen serpent. [7]

The story of Balaam, containing several repetitions and variations, seems to have been woven together from J and E. In the J sections, Balaam is a prophet of Yahweh who refuses to practice sorcery. In the E passages. it is not Yahweh but Elohim who speaks to Balaam. The prophetic poems of Balaam may be older than either J or E, and the story of Balaam's being blamed for Israel's seduction by the Moabite women is clearly discordant with J's view of the prophet as courageously devoted to Yahweh.

Tantalizing hints of early traditions are found in certain places in the Book of Numbers. For example, the story of Miriam and Aaron opposing Moses has given rise to speculation of competing traditions in which the figures of Miriam, Aaron, and Moses played leading roles.[8] In this vein, the bronze serpent of Moses is particularly interesting. Housed for centuries in the Temple of Jerusalem, this statue was eventually condemned as an idol in the time of King Hezekiah and consequently destroyed. Some scholars hold that the serpent, associated with the goddess Ashera, originally the consort of Yahweh, may once have been seen as compatible with Yahweh worship, but later, as the "Yahweh-only" movement came to the fore, became unacceptable. J's portrayal of Balaam as a prophet of Yahweh operating in Moab also offers food for thought as to the possibility that the God of Israel was worshiped early on by the Moabites, identified in biblical tradition as descendants of Abraham's nephew Lot. The reference to a now lost "book of the wars of the Lord," occurring in Numbers 21:14, has given rise to much discussion.

Notes

- ↑ This account contradicts that of Leviticus 10:4, which specifies that Mishael and Elzaphan, cousins of Moses and Aaron, replaced Nadab and Abihu as priests.

- ↑ The penalty for adultery, if a woman were to admit to it, is death by stoning.

- ↑ Famous Nazirites include Samson in the Hebrew Bible and John the Baptist in the New Testament.

- ↑ In the Book of Deuteronomy, Aaron dies much earlier in the saga, shortly after the episode of the Golden Calf.

- ↑ Later referred to as the Nehushtan, this bronze serpent icon was reportedly an object of worship for centuries in the Temple of Jerusalem until it was declared to be idolatrous during the time of King Hezekiah (2 Kings 18:4). The story of a bronze image of a snake crafted by Moses at God's command has led some scholars to speculate that the commandment against "graven images" may have originated in a later period.

- ↑ The Book of Deuteronomy, on the other hand, encourages Levites to move to the capital, where they will be recognized as priests. It also bans them from performing sacrifices outside of the central sanctuary.

- ↑ Book of Numbers. JewishEncyclopedia.com. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- ↑ Frank Moore Cross, Canaanite Myth and Hebrew Epic (Harvard University Press, 1973, ISBN 978-0674091764), 203.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Carmy, Shalom, (ed.) Modern Scholarship in the Study of Torah: Contributions and Limitations. Jason Aronson, 1996. ISBN 978-1568214504

- Cross, Frank Moore. Canaanite Myth and Hebrew Epic. Harvard University Press 1973. ISBN 978-0674091764

- Dever, William G. What Did the Biblical Writers Know and When Did They Know It?: What Archeology Can Tell Us About the Reality of Ancient Israel.. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2002. ISBN 978-0802821263

- Friedman, Richard E. Who Wrote the Bible? Harper, San Francisco, 1997. ISBN 978-0060630355

- Kaufmann, Yehezkel, Greenberg, Moishe (translator). The Religion of Israel, from Its Beginnings to the Babylonian Exile. University of Chicago Press, 1960. ISBN 978-0226427287

- Mendenhall, George E. Ancient Israel's Faith and History: An Introduction to the Bible in Context. Westminster: John Knox Press, 2001. ISBN 0664223133

- Van Seters, Jonathan. The Life of Moses: The Yahwist as Historian in Exodus-Numbers. Westminster: John Knox Press, 1994. ISBN 978-0664223632

External links

All links retrieved November 16, 2022.

- New Revised Standard Version. bible.oremus.org.

- Book of Numbers www.JewishEncyclopedia.com.

| |||||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.