| Category |

| Jews · Judaism · Denominations |

|---|

| Orthodox · Conservative · Reform |

| Haredi · Hasidic · Modern Orthodox |

| Reconstructionist · Renewal · Rabbinic · Karaite |

| Jewish philosophy |

| Principles of faith · Minyan · Kabbalah |

| Noahide laws · God · Eschatology · Messiah |

| Chosenness · Holocaust · Halakha · Kashrut |

| Modesty · Tzedakah · Ethics · Mussar |

| Religious texts |

| Torah · Tanakh · Talmud · Midrash · Tosefta |

| Rabbinic works · Kuzari · Mishneh Torah |

| Tur · Shulchan Aruch · Mishnah Berurah |

| Ḥumash · Siddur · Piyutim · Zohar · Tanya |

| Holy cities |

| Jerusalem · Safed · Hebron · Tiberias |

| Important figures |

| Abraham · Isaac · Jacob/Israel |

| Sarah · Rebecca · Rachel · Leah |

| Moses · Deborah · Ruth · David · Solomon |

| Elijah · Hillel · Shammai · Judah the Prince |

| Saadia Gaon · Rashi · Rif · Ibn Ezra · Tosafists |

| Rambam · Ramban · Gersonides |

| Yosef Albo · Yosef Karo · Rabbeinu Asher |

| Baal Shem Tov · Alter Rebbe · Vilna Gaon |

| Ovadia Yosef · Moshe Feinstein · Elazar Shach |

| Lubavitcher Rebbe |

| Jewish life cycle |

| Brit · B'nai mitzvah · Shidduch · Marriage |

| Niddah · Naming · Pidyon HaBen · Bereavement |

| Religious roles |

| Rabbi · Rebbe · Hazzan |

| Kohen/Priest · Mashgiach · Gabbai · Maggid |

| Mohel · Beth din · Rosh yeshiva |

| Religious buildings |

| Synagogue · Mikvah · Holy Temple / Tabernacle |

| Religious articles |

| Tallit · Tefillin · Kipa · Sefer Torah |

| Tzitzit · Mezuzah · Menorah · Shofar |

| 4 Species · Kittel · Gartel · Yad |

| Jewish prayers |

| Jewish services · Shema · Amidah · Aleinu |

| Kol Nidre · Kaddish · Hallel · Ma Tovu · Havdalah |

| Judaism & other religions |

| Christianity · Islam · Catholicism · Christian-Jewish reconciliation |

| Abrahamic religions · Judeo-Paganism · Pluralism |

| Mormonism · "Judeo-Christian" · Alternative Judaism |

| Related topics |

| Criticism of Judaism · Anti-Judaism |

| Antisemitism · Philo-Semitism · Yeshiva |

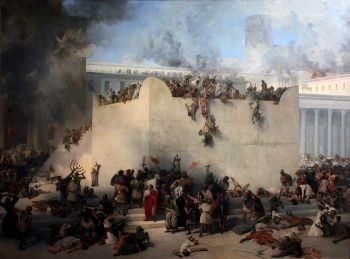

Joshua ben Hananiah (Hebrew: יהושע בן חנניה d. 131 C.E.), also known as Rabbi Joshua was a leading rabbinical sage of the first half-century following the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem as a result of the First Jewish Revolt, 66-70 C.E.

A disciple of Johanan ben Zakkai, he was an opponent of asceticism who represented the more liberal school of Hillel against the strict legalism of the house of Shammai, especially in disputes with Johanan's other leading pupil, Eliezer ben Hyrcanus. Rabbi Joshua also worked in concert with Gamaliel II, the president of the emerging rabbinical academy at Jamnia, to promote Hillel's views, but he ran afoul of Gamaliel on issues of authority. He went on to become president of the rabbinical council after Gamaliel's death. A rich tradition has developed concerning Rabbi Joshua's interactions with Emperor Hadrian, although the historicity of some of these conversations is dubious.

Joshua's character was that of a peacemaker who respected and forgave even his strongest opponents. His influence is thought to have prevented the Jews from a second violent rebellion against Rome. After his death, however, his own most prominent disciple, Rabbi Akiba, became a supporter of the messianic revolt led by Simon Bar Kochba against Rome, which led to tragic results.

Together with Johanan ben Zakkai, Gamaliel II, and Akiba, Joshua ben Hananiah was one of the key founders of the rabbinic Judaism, which has been at the center of Jewish life and civilization for the last two millennia. He is one of the most quoted sages of the Mishnah, the Talmud, and other classical Jewish literature.

Early years

Rabbi Joshua was of Levitical descent (Ma'as. Sh. v. 9), and had served in the Temple of Jerusalem as a member of the class of singers. His mother intended him for a life of study and reportedly carried Joshua in his cradle into the synagogue, so that his ears might become accustomed to the sounds of the words of the Torah.

Joshua became one of the inner circle of the pupils of Rabbi Johanan ben Zakkai (Ab. ii. 8). Rabbi Johanan praised him in the words from Ecclesiastes 4:12: "A threefold cord is not quickly broken," thought to mean in Joshua, the three branches of traditional Jewish learning at the time—Midrash, Halakah, and Aggadah—were united in a firm whole. Tradition places him at the head of Johanan's disciples along with Rabbi Eliezer ben Hyrcanus. These two are frequently mentioned as upholders of opposite views, with Joshua representing the house of Hillel and Eliezer representing that of Shammai. Eliezer and Joshua cooperated together, however, to rescue their teacher Johanan from the besieged city of Jerusalem in the closing days of the Jewish Revolt, reportedly smuggling him out of the city in a coffin.

An opponent of asceticism

After the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem Joshua opposed the exaggerated asceticism with which many wished to show their grief, such as going without meat and wine because the sacred altar, on which they had sacrificed animals and poured libations of wine, had been destroyed. He argued that to carry this policy to its logical conclusion, they ought to eat no figs or grapes either, since no more first-fruits were offered, and that they ought even to refrain from bread, since the loaves of the feast of first-fruits could no longer be sacrificed (Tosef., Sotah, end; B. B. 60b).

Joshua's opposition to asceticism is also thought to be due to his mild and temperate nature. In regard to the severe regulations which had been adopted by the school of Shammai shortly before the destruction of the Temple, he said: "On that day they overstepped the boundary."

Joshua saw the greatest danger to the community in the sickly offshoots of supposed piety. Classes of people he condemned as "enemies of general prosperity" included:

- Foolishly pious men

- Sly sinners who appear pious

- Women who show an over-pious bearing

- Hypocrites who pretend to be saints (Sotah iii. 4, 21b; Yer. Sotah 21b)

When Johanan ben Zakkai asked his pupils concerning the best standard of conduct, Joshua answered that one should seek association with a good companion and avoid a bad one. He recommended temperance and the love of humankind as the best assurance of individual happiness. On the other hand, holding grudges, lustful passion, and hatred of humankind brings only loss and ultimately death (Ab. ii. 11).

Various anecdotes illustrate the opposition between Joshua, who represented the teachings of Hillel, and his colleague Eliezer, who represented the teachings of Shammai, much in the same way as the opposition between Hillel and Shammai is depicted elsewhere (Gen. R. lxx; Eccl. R. i. 8; Kid. 31a).

Relations with Gamaliel II

Joshua's permanent residence was located between Jamnia and Lydda, where he was a sewer by trade (Yer. Ber. 7d). This seemingly menial occupation, however, did not diminish the respect paid to him as one of the influential members of the emerging rabbinical academy at Jamnia.

After the death of Johanan ben Zakkai (c. 90 C.E.), Rabbi Joshua was a supporter of the efforts of Gamaliel II, the president of the academy, to promote the views of Hillel's followers over those of Shammai's and bring to an end the discord which had so long existed between the schools. Nevertheless, he and Gamaliel clashed severely on questions of authority, with Joshua apparently feeling that Gamaliel was too heavy-handed. On one occasion, Gamaliel humiliated Joshua when the authority of the president was in question (R. H. 25a; Yer. R. H. 58b). A subsequent similar mistreatment of Joshua by Gamaliel was so offensive to the rabbinical assembly that it occasioned Gamaliel's temporary removal from office. He soon obtained Joshua's forgiveness, and this opened the way for his reinstatement. However, Gamaliel was now obliged to share his office with Eleazar ben Azariah (not to be confused with Eliezer ben Hyrcanus]]), who had earlier been appointed his successor (Ber. 28a).

In order to plead the case of the Palestinian Jews at Rome, the co-presidents, Gamaliel and Eleazar, went as their primary representatives, with rabbis Joshua and Akiba accompanying them. This journey of the "elders" to Rome furnished material for many narratives and legends. In one of these, the Romans called on Rabbi Joshua to give proofs from the Bible of the resurrection of the dead and of the foreknowledge of God (Sanh. 90b). In another, Joshua came to the aid of Gamaliel when the latter was unable to answer the question of a philosopher (Gen. R. xx.). In one anecdote, Joshua's astronomical knowledge enabled him to calculate that a comet would appear in the course of a sea voyage in which he and Gamaliel were involved (Hor. 10a).

Council president

After Gamaliel's death, the presidency of the rabbinical council fell to Joshua, since Eleazar ben Azariah had apparently already died, and Eliezer ben Hyrcanus was under a ban of excommunication due to his irascible opposition to the will of the majority and his sewing the seeds of disunity. Later, Joshua, hearing of Eliezer's mortal illness, went to his deathbed despite the ban against him, and sought to console him: "O master, thou art of more value to Israel than God's gift of the rain," he declared, "since the rain gives life in this world only, whereas thou givest life both in this world and in the world to come" (Mek., Yitro, Bachodesh, 10; Sifre, Deut. 32). After Eliezer's death, Joshua rescinded the excommunication against his old colleague and opponent. Later, when other scholars contested some of Eliezer's legal rulings, Joshua said to them: "One should not oppose a lion after he is dead" (Gittin 83a; Yer. Git. 50a).

Under Hadrian

In the beginning of Hadrian's rule, Joshua, as council president, acted as the leader of the Jewish people and a proponent of peace. When permission to rebuild the Temple of Jerusalem was refused, he turned the people away from thoughts of revolt against Rome by a speech in which he skillfully made use of Aesop's fable of the lion and the crane (Gen. R. lxiv., end). About the same time, Joshua—ever the Hillelite—used his eloquence to prevent the whole area of the Temple from being pronounced unclean because one human bone had been found in it (Tosef., 'Eduy. iii. 13; Zeb. 113a). Joshua lived to witness Hadrian's visit to Palestine, and in 130 C.E., he followed the emperor to Alexandria.

The conversations between Joshua and Hadrian, as they have been preserved in the Talmud and the Midrash, have been greatly exaggerated by tradition, but they nevertheless present a fair picture of the intercourse between the witty Jewish scholar and the active, inquisitive emperor. In Palestinian sources, Joshua answers various questions of the emperor about how God created the world (Gen. R. x.), the nature of the angels (ib. lxxviii., beginning; Lam. R. iii. 21), the resurrection of the body (Gen. R. xxviii.; Eccl. R. xii. 5), and with regard to the Ten Commandments (Pesiḳ. R. 21). In the Babylonian Talmud three conversations are related, in which Joshua silences the emperor's mockery of the Jewish conception of God by proving to him God's incomparable greatness and majesty (Ḥul. 59b, 60a). Joshua also rebukes the emperor's daughter when she makes a mocking comment about the God of the Jews (ibid. 60a). In another place, she is made to repent for having made fun of Joshua's appearance (Ta'an. on Ned. 50b). In a dispute with a Jewish Christian, Joshua dramatically maintained that God's protective hand was still stretched over Israel (Hagigah 5b). Some of the questions addressed to Joshua by the Athenian wise men, found in a long story in the Babylonian Talmud (Bek. 8b et seq.), contain polemical expressions against Christianity.

Teachings

Joshua's controversies with his prominent contemporaries occupy an important place in Jewish tradition. The differences of opinion between Joshua and Eliezer ben Hyrcanus are especially notable, dealing with cosmology, eschatology, the advent and role of the Messiah, the world to come, the resurrection, and biblical interpretation.

One of their disagreements—reflecting the difference between the schools of Hillel and Shammai—relates to the Jewish attitude toward Gentiles. Commenting on Psalm 9:18, Joshua taught there are pious people among the Gentiles who will have a share in the life everlasting (Tosef., Sanh. xiii. 2; comp. Sanh. 105a). Joshua also represented the liberal attitude of Hillel's school regarding life in general. Jewish religious holidays, he said, are not meant to be droll affairs devoid of joy, but are intended to be employed one-half for worldly enjoyment, one-half for study (Pes. 68b; Betzah 15b). From Ruth 2:19 he concluded that the poor person who receives does more for the giver than the giver does for the recipient (Lev. R. xxxiv.; Ruth R. ad loc.).

Rabbi Joshua is regarded by posterity as a man always ready with an answer, and as the representative of Jewish wit and wisdom. Others of his sayings and teachings include:

- "Why is a man easy, and a woman difficult, to persuade?"

- Man was created out of earth, which easily dissolves in water, but woman was created from bone, which is not affected by water.

- "No one ever overcame me except a woman, a boy, and a maid" (Er. 53b).

Death and legacy

It is related that when Rabbi Joshua was about to die, the scholars standing around his bed mourned, saying: "How shall we maintain ourselves against the unbelievers?" After his death, Joshua's importance was extolled in the words: "Since Rabbi Joshua died, good counsel has ceased in Israel" (Baraita, Sotah, end).

Not long after Joshua's death his peace-making spirit gave way to the men of violent action. The messianic leader Simon Bar Kochba raised a revolt against Rome that was enthusiastically greeted by Joshua's most influential pupil, Rabbi Akiba. The rebellion ended tragically with more than 100,000 Jewish lives lost and the Jews banned from Jerusalem. That such a rebellion had not been undertaken earlier is thought by many to be due to Rabbi Joshua's influence.

The work of rabbis Johanan ben Zakkai, Gamaliel II, Joshua ben Hananiah, and Akiba set the tone of rabbinic Judaism for the next two millennia. Facing a crisis in which the destruction of the Temple of Jerusalem had destroyed the physical and spiritual center of Jewish religious life, they adopted the flexible and broad-minded principles of Hillel and rejected the narrow legalism of Shammai, creating a tradition which welcomes debate and tolerates a broad range of opinion as authentically Jewish. That Judaism was able not only to survive but to create a rich and diverse intellectual tradition—despite the relatively hostile environments of Christian and Muslim civilization—is a testimony to the wisdom and inspiration of Rabbi Joshua and his colleagues and disciples.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Duker, Jonathan. The Spirits Behind the Law: The Talmudic Scholars. Jerusalem: Urim, 2007. ISBN 9789657108970.

- Green, William Scott. The Traditions of Joshua Ben Ḥananiah. Studies in Judaism in late antiquity, v. 29. Leiden: Brill, 1981. ISBN 9789004063198.

- —. Persons and Institutions in Early Rabbinic Judaism. Brown Judaic studies, no. 3. Missoula, Mont: Published by Scholars Press for Brown University, 1977. ISBN 9780891301318.

- Kalmin, Richard Lee. The Sage in Jewish Society of Late Antiquity. New York: Routledge, 1999. ISBN 978-0415196956.

- Neusner, Jacob. First-Century Judaism in Crisis: Yohanan Ben Zakkai and the Renaissance of Torah. New York: Ktav Pub. House, 1982. ISBN 9780870687280.

- Podro, Joshua. The Last Pharisee; The Life and Times of Rabbi Joshua Ben Hananyah, a First-Century Idealist. London: Vallentine, Mitchell, 1959. OCLC 781902.

This article incorporates text from the 1901–1906 Jewish Encyclopedia, a publication now in the public domain.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.