| Western Philosophers Medieval Philosophy | |

|---|---|

| |

| Name: Thomas Aquinas | |

| Birth: c. January 28, 1225 (Castle of Roccasecca, near Aquino, Italy) | |

| Death: March 7, 1274 (Fossanova Abbey, Lazio, Italy) | |

| School/tradition: Scholasticism, Founder of Thomism | |

| Main interests | |

| Metaphysics (incl. Theology), Logic, Mind, Epistemology, Ethics, Politics | |

| Notable ideas | |

| Five Proofs for God's Existence, Principle of double effect | |

| Influences | Influenced |

| Aristotle, Albertus Magnus, Paul the Apostle, Boethius, Eriugena, Anselm, Averroes, Maimonides, St. Augustine, Algazel, Avicenna, John of Damascus | Giles of Rome, Godfrey of Fontaines, Jacques Maritain, G. E. M. Anscombe, Meister Eckhart, John Locke, Dante, G. K. Chesterton |

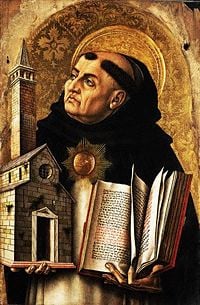

Saint Thomas Aquinas, O.P. (also Thomas of Aquin, or Aquino; c. 1225 – March 7, 1274) was an Italian Roman Catholic priest in the Order of Preachers (more commonly known as the Dominican Order), a philosopher and theologian in the scholastic tradition, known as Doctor Angelicus, Doctor Universalis and Doctor Communis. He is the foremost classical proponent of natural theology, and the father of the Thomistic school of philosophy and theology.

Saint Thomas Aquinas is held in the Roman Catholic Church to be the model teacher for those studying for the priesthood (Code of Canon Law, Can. 252, §3). The work for which he is best-known is the Summa Theologica. One of the 33 Doctors of the Church, he is considered by many Roman Catholics to be the Catholic Church's greatest theologian. Consequently, many institutions of learning have been named after him.

Biography

Early life

Thomas Aquinas was born around 1225 at his father Count Landulf's castle of Roccasecca in the kingdom of Naples. Today, this castle is in the Province of Frosinone, in the Regione Lazio. Through his mother, Theodora Countess of Theate, Aquinas was related to the Hohenstaufen dynasty of Holy Roman emperors.[1] Landulf's brother Sinibald was abbot of the original Benedictine monastery at Monte Cassino. The family intended for Aquinas to follow his uncle into that position. This would have been a normal career path for a younger son of southern Italian nobility.[1]

At the age of five, Aquinas began his early education at the monastery. When he was 16, he left the University of Naples, where he studied for six years. Aquinas had come under the influence of the Dominicans, who wished to enlist the ablest young scholars of the age. The Dominicans and the Franciscans represented a revolutionary challenge to the well-established clerical systems of Medieval Europe.[1]

Aquinas's change of heart did not please his family. On the way to Rome, his brothers seized him and took him back to his parents at the castle of San Giovanni. He was held captive for a year so he would renounce his new aspiration. According to Aquinas's earliest biographers, the family even brought a woman to tempt him, but he drove her away. Finally, Pope Innocent IV intervened, and Aquinas assumed the habit of Saint Dominic in his seventeenth year.[1]

His superiors saw his great aptitude for theological study. In late 1244, they sent him to the Dominican school in Cologne, where Albertus Magnus was lecturing on philosophy and theology. In 1245, Aquinas accompanied Albertus to the University of Paris, where they remained for three years. During this time, Aquinas threw himself into the controversy between the university and the Friar-Preachers about the liberty of teaching. Aquinas actively resisted the university's speeches and pamphlets. When the Pope was alerted of this dispute, the Dominicans selected Aquinas to defend his order. He did so with great success. He even overcame the arguments of Guillaume de St Amour, the champion of the university, and one of the most celebrated men of the day.[1]

Aquinas then graduated as a bachelor of theology. In 1248, he returned to Cologne, where he was appointed second lecturer and magister studentium. This year marks the beginning of his literary activity and public life.[1]

For several years, Aquinas remained with Albertus Magnus. Aquinas's long association with this great philosopher-theologian was the most important influence in his development. In the end, he became a comprehensive scholar who permanently utilized Aristotle's method.[1]

Career

In 1252, Aquinas went to Paris for his master's degree. He had some difficulty because the professoriate of the university was attacking the mendicant orders, but ultimately, he received the degree.

In 1256, Aquinas, along with his friend Bonaventura, was named doctor of theology and began to lecture on theology in Paris and Rome and other Italian towns. From this time on, his life was one of incessant toil. Aquinas continually served in his order, frequently made long and tedious journeys, and constantly advised the reigning pontiff on affairs of state.[1]

In 1259, Aquinas was present at an important meeting of his order at Valenciennes. At the solicitation of Pope Urban IV, he moved to Rome no earlier than late 1261. In 1263, he attended the London meeting of the Dominican order. In 1268, he lectured in Rome and Bologna. Throughout these years, he remained engaged in the public business of the Catholic Church.[2]

From 1269 to 1271, Aquinas was again active in Paris. He lectured to the students, managed the affairs of the Catholic Church, and advised the king, Louis VIII, his kinsman, on affairs of state.[3] In 1272, the provincial chapter at Florence empowered him to begin a new studium generale at a location of his choice. Later, the chief of his order and King Charles II brought him back to the professor's chair at Naples.[4]

All this time, Aquinas preached every day, and he wrote homilies, disputations, and lectures. He also worked diligently on his great literary work, the Summa Theologica. The Catholic Church offered to make him archbishop of Naples and abbot of Monte Cassino, but he refused both.[3]

It should be noted that, as a Dominican Friar, Aquinas was supposed to participate in the mortification process. He did not; a remarkable thing considering how devoted to his faith he was known to be. At his canonization trial, it became evident he did not practice such rites. "The forty-two witnesses at the canonization trial had little to report concerning extraordinary acts of penance, sensational deeds, and mortifications… they could only repeat unanimously, again and again: Thomas had been a pure person, humble, simple, peace-loving, given to contemplation, moderate, a lover of poetry." These endearing qualities helped him in his beatification. The witnesses praised Thomas for his rational thought.

Aquinas had a mystical experience while celebrating Mass on December 6, 1273. At this point, he set aside his Summa. When asked why he had stopped writing, Aquinas replied, "I cannot go on …. All that I have written seems to me like so much straw compared to what I have seen and what has been revealed to me." Later, others reported that Aquinas heard a voice from a cross that told him he had written well. On one occasion, monks claimed to have found him levitating. The twentieth century Roman Catholic writer/convert G. K. Chesterton describes these and other stories in his work on Aquinas, Thomas Aquinas: The Dumb Ox, a title based on early impressions that Aquinas was not proficient in speech.[5] Chesterton quotes Albertus Magnus' refutation of these impressions: "You call him 'a dumb ox,' but I declare before you that he will yet bellow so loud in doctrine that his voice will resound through the whole world."[6]

Aquinas had a dark complexion, large head and receding hairline, and he was of large stature. His manners showed his breeding, for people described him as refined, affable, and lovable. In arguments, he maintained self-control and won over his opponents by his personality and great learning. His tastes were simple. He impressed his associates with his power of memory. When absorbed in thought, he often forgot his surroundings, but he was able to express his thoughts systematically, clearly, and simply. Because of his keen grasp of his materials, Aquinas does not, like Duns Scotus, make the reader his companion in the search for truth. Rather, he teaches authoritatively. On the other hand, he felt dissatisfied by the insufficiency of his works as compared to the divine revelations he had received.[4]

Death and canonization

In January 1274, Pope Gregory X directed Aquinas to attend the Second Council of Lyons. Aquinas's task was to investigate and, if possible, settle the differences between the Greek and Latin churches. Far from healthy, he undertook the journey. On the way, he stopped at the castle of a niece and there became seriously ill. Aquinas desired to end his days in a monastery. However, he was unable to reach a house of the Dominicans, so he was taken to the Cistercian monastery of Fossa Nuova. After a lingering illness of seven weeks, Aquinas died on March 7, 1274.[4]

Dante (Purg. xx. 69) asserts that Aquinas was poisoned by the order of Charles of Anjou. Villani (ix. 218) quotes this belief, and the Anonimo Fiorentino describes the crime and its motive. But the historian Muratori reproduced the account of one of Aquinas's friends, and this version of the story gives no hint of foul play.[3]

Aquinas made a remarkable impression on all who knew him. He received the title doctor angelicas (Angelic Doctor).[4] In The Divine Comedy, Dante sees the glorified spirit of Aquinas in the Heaven of the Sun with the other great exemplars of religious wisdom.

In 1319, the Roman Catholic Church began preliminary investigations to Aquinas's canonization. On July 18, 1323, Pope John XXII pronounced Aquinas's sainthood at Avignon.[4] In 1567, Pope Pius V ranked the festival of Saint Thomas Aquinas with those of the four great Latin fathers: Ambrose, Augustine, Jerome, and Gregory.

Aquinas's Summa Theologica was deemed so important that at the Council of Trent, it was placed upon the altar beside the Bible and the Decretals.[7] Only Augustine has had an equal influence on the theological thought and language of the Western Catholic church. In his Encyclical of August 4, 1879, Pope Leo XIII stated that Aquinas's theology was a definitive exposition of Roman Catholic doctrine. Thus, he directed the clergy to take the teachings of Aquinas as the basis of their theological positions. Also, Leo XIII decreed that all Roman Catholic seminaries and universities must teach Aquinas's doctrines, and where Aquinas did not speak on a topic, the teachers were "urged to teach conclusions that were reconcilable with his thinking."

In 1880, Aquinas was declared patron of all Roman Catholic educational establishments. In a monastery at Naples, near the cathedral of Saint Januarius, a cell in which he supposedly lived is still shown to visitors. Aquinas's feast day was changed after Vatican II to January 28. Until then, and still observed by traditionalists, his feast day was on the day of his death, March 7. His remains were placed in the Church of the Jacobins in Toulouse in 1369. Between 1789 and 1974, they were held in Saint Sernin basilica of Toulouse. In 1974, they were returned to the Church of the Jacobins, where they have remained ever since.

Influences

Margaret Smith writes in her book Al-Ghazali: The Mystic (London: 1944): "There can be no doubt that Al-Ghazali’s works would be among the first to attract the attention of these European scholars" (220). Then she emphasizes, "The greatest of these Christian writers who was influenced by Al-Ghazali was St. Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274), who made a study of the Arabic writers and admitted his indebtedness to them. He studied at the University of Naples where the influence of Arab literature and culture was predominant at the time."

"A careful study of Ghazali's works will indicate how penetrating and widespread his influence was on the Western medieval scholars. A case in point is the influence of Ghazali on St. Thomas Aquinas—who studied the works of Islamic philosophers, especially Ghazali's, at the University of Naples. In addition, Aquinas' interest in Islamic studies could be attributed to the infiltration of ‘Latin Averroism’ in the 13th century, especially [at the University of] Paris."[8]

Philosophy

- "Nihil est in intellectu quod non sit prius in sensu." (Nothing is in the intellect that was not first in the senses) – Aquinas's peripatetic axiom

The philosophy of Aquinas has exerted enormous influence on subsequent Christian theology, especially that of the Roman Catholic Church, extending to Western philosophy in general, where he stands as a vehicle and modifier of Aristotelianism. Philosophically, his most important and enduring work is the Summa Theologica, in which he expounds his systematic theology of the quinquae viae.

Epistemology

Aquinas believed "that for the knowledge of any truth whatsoever man needs Divine help, that the intellect may be moved by God to its act." However, he believed that human beings have the natural capacity to know many things without special divine revelation, even though such revelation occurs from time to time, "especially in regard to [topics of] faith."[9] Aquinas was also an Aristotelian and an empiricist. He substantially influenced these two streams of Western thought.

Revelation

Aquinas believed that truth is known through reason (natural revelation) and faith (supernatural revelation). Supernatural revelation is revealed through the prophets, Holy Scripture, and the Magisterium, the sum of which is called "tradition." Natural revelation is the truth available to all people through their human nature; certain truths all men can attain from correct human reasoning. For example, he felt this applied to rational proofs for the existence of God.

|

Part of the Politics series on |

| Parties |

|

Christian Democratic parties |

| Ideas |

|

Social conservatism |

| Important documents |

|

Rerum Novarum (1891) |

| Important figures |

|

Thomas Aquinas · John Calvin |

| Politics Portal · edit |

Though one may deduce the existence of God and His Attributes (One, Truth, Good, Power, Knowledge) through reason, certain specifics may be known only through special revelation (Like the Trinity). In Aquinas's view, special revelation is equivalent to the revelation of God in Jesus Christ. The major theological components of Christianity, such as the Trinity and the Incarnation, are revealed in the teachings of the Roman Catholic Church and the Scriptures and may not otherwise be deduced.

Special revelation (faith) and natural revelation (reason) are complementary rather than contradictory in nature, for they pertain to the same unity: truth.

Analogy

An important element in Aquinas's philosophy is his theory of analogy. Aquinas noted three forms of descriptive language: univocal, analogical, and equivocal.[10]

- Univocality is the use of a descriptor in the same sense when applied to two objects.

- Analogy, Aquinas maintained, occurs when a descriptor changes some but not all of its meaning. Analogy is necessary when talking about God, for some of the aspects of the divine nature are hidden (Deus absconditus) and others revealed (Deus revelatus) to finite human minds. In Aquinas's mind, we can know about God through his creation (general revelation), but only in an analogous manner. We can speak of God's goodness only by understanding that goodness as applied to humans is similar to, but not identical with, the goodness of God.[11]

- Equivocation is the complete change in meaning of the descriptor and is an informal fallacy.

Ethics

Aquinas's ethics are based on the concept of "first principles of action."[12] In his Summa Theologica he wrote:

Virtue denotes a certain perfection of a power. Now a thing's perfection is considered chiefly in regard to its end. But the end of power is act. Wherefore power is said to be perfect, according as it is determinate to its act.[13]

Aquinas defined the four cardinal virtues as prudence, temperance, justice, and fortitude. The cardinal virtues are natural and revealed in nature, and they are binding on everyone. There are, however, three theological virtues: faith, hope, and charity. These are supernatural and are distinct from other virtues in their object, namely, God:

Now the object of the theological virtues is God Himself, Who is the last end of all, as surpassing the knowledge of our reason. On the other hand, the object of the intellectual and moral virtues is something comprehensible to human reason. Wherefore the theological virtues are specifically distinct from the moral and intellectual virtues.[14]

Furthermore, Aquinas distinguished four kinds of law: eternal, natural, human, and divine. Eternal law is the decree of God that governs all creation. Natural law is the human "participation" in the eternal law and is discovered by reason.[15] Natural law is based on "first principles":

… this is the first precept of the law, that good is to be done and promoted, and evil is to be avoided. All other precepts of the natural law are based on this ….[16]

The desire to live and to procreate are counted by Aquinas among those basic (natural) human values on which all human values are based.

Human law is positive law: the natural law applied by governments to societies. Divine law is the specially revealed law in the scriptures.

Aquinas also greatly influenced Roman Catholic understandings of mortal and venial sins.

Aquinas denied that human beings have any duty of charity to animals because they are not persons. Otherwise, it would be unlawful to use them for food. But this does not give us license to be cruel to them, for "cruel habits might carry over into our treatment of human beings."[17]

Theology

| Part of a series of articles on Christianity | ||||||

| ||||||

|

Foundations Bible Christian theology History and traditions

Topics in Christianity Important figures | ||||||

Aquinas viewed theology, or the sacred doctrine, as a science, the raw material data of which consists of written scripture and the tradition of the Catholic church. These sources of data were produced by the self-revelation of God to individuals and groups of people throughout history. Faith and reason, while distinct but related, are the two primary tools for processing the data of theology. Aquinas believed both were necessary - or, rather, that the confluence of both was necessary - for one to obtain true knowledge of God. Aquinas blended Greek philosophy and Christian doctrine by suggesting that rational thinking and the study of nature, like revelation, were valid ways to understand God. According to Aquinas, God reveals himself through nature, so to study nature is to study God. The ultimate goals of theology, in Aquinas’ mind, are to use reason to grasp the truth about God and to experience salvation through that truth.

Nature of God

Aquinas felt that the existence of God is neither self-evident nor beyond proof. In the Summa Theologica, he considered in great detail five rational proofs for the existence of God. These are widely known as the quinquae viae, or the "Five Ways."

Concerning the nature of God, Aquinas felt the best approach, commonly called the via negativa, is to consider what God is not. This led him to propose five positive statements about the divine qualities:[18]

- God is simple, without composition of parts, such as body and soul, or matter and form.

- God is perfect, lacking nothing. That is, God is distinguished from other beings on account of God's complete actuality.

- God is infinite. That is, God is not finite in the ways that created beings are physically, intellectually, and emotionally limited. This infinity is to be distinguished from infinity of size and infinity of number.

- God is immutable, incapable of change on the levels of God's essence and character.

- God is one, without diversification within God's self. The unity of God is such that God's essence is the same as God's existence. In Aquinas's words, "in itself the proposition 'God exists' is necessarily true, for in it subject and predicate are the same."

In this approach, he is following, among others, the Jewish philosopher Maimonides.[19]

Nature of the Trinity

Aquinas argued that God, while perfectly united, also is perfectly described by three interrelated persons. These three persons (Father, Son, and Holy Spirit) are constituted by their relations within the essence of God. The Father generates the Son (or the Word) by the relation of self-awareness. This eternal generation then produces an eternal Spirit "who enjoys the divine nature as the Love of God, the Love of the Father for the Word."

This Trinity exists independently from the world. It transcends the created world, but the Trinity also decided to communicate God's self and God's goodness to human beings. This takes place through the Incarnation of the Word in the person of Jesus Christ and through the indwelling of the Holy Spirit (indeed, the very essence of the Trinity itself) within those who have experienced salvation by God.[20]

Nature of Jesus Christ

In the Summa Theologica, Aquinas begins his discussion of Jesus Christ by recounting the biblical story of Adam and Eve and by describing the negative effects of original sin. The purpose of Christ's Incarnation was to restore human nature by removing "the contamination of sin," which humans cannot do by themselves. "Divine Wisdom judged it fitting that God should become man, so that thus one and the same person would be able both to restore man and to offer satisfaction."[21]

Aquinas argued against several specific contemporary and historical theologians who held differing views about Christ. In response to Photinus, Aquinas stated that Jesus was truly divine and not simply a human being. Against Nestorius, who suggested that God merely inhabited the body of Christ, Aquinas argued that the fullness of God was an integral part of Christ's existence. However, countering Apollinaris' views, Aquinas held that Christ had a truly human (rational) soul, as well. This produced a duality of natures in Christ, contrary to the teachings of Arius. Aquinas argued against Eutyches that this duality persisted after the Incarnation. Aquinas stated that these two natures existed simultaneously yet distinguishably in one real human body, unlike the teachings of Manichaeus and Valentinus.[22]

In short, "Christ had a real body of the same nature of ours, a true rational soul, and, together with these, perfect deity." Thus, there is both unity (in his one hypostasis) and diversity (in his two natures, human and divine) in Christ.[23]

Goal of human life

In Aquinas's thought, the goal of human existence is union and eternal fellowship with God. Specifically, this goal is achieved through the beatific vision, an event in which a person experiences perfect, unending happiness by comprehending the very essence of God. This vision, which occurs after death, is a gift from God given to those who have experienced salvation and redemption through Christ while living on earth.

This ultimate goal carries implications for one's present life on earth. Aquinas stated that an individual's will must be ordered toward right things, such as charity, peace, and holiness. He sees this as the way to happiness. Aquinas orders his treatment of the moral life around the idea of happiness. The relationship between will and goal is antecedent in nature "because rectitude of the will consists in being duly ordered to the last end [that is, the beatific vision]." Those who truly seek to understand and see God will necessarily love what God loves. Such love requires morality and bears fruit in everyday human choices.[24]

Modern influence

Many modern ethicists both within and outside the Roman Catholic church (notably Philippa Foot and Alasdair MacIntyre) have recently commented on the possible use of Aquinas's virtue ethics as a way of avoiding utilitarianism or Kantian deontology. Through the work of twentieth century philosophers such as Roman Catholic convert Elizabeth Anscombe (especially in her book Intention), Aquinas's principle of double effect specifically and his theory of intentional activity generally have been influential.

It is remarkable that Aquinas's aesthetic theories, especially the concept of claritas, deeply influenced the literary practice of modernist writer James Joyce, who used to extol Aquinas as being second only to Aristotle among Western philosophers. The influence of Aquinas's aesthetics also can be found in the works of the Italian semiotician Umberto Eco, who wrote an essay on aesthetic ideas in Aquinas [25](published in 1956 and republished in 1988 in a revised edition).

See also

- Dominican Order

- Thomism

- Aristotelianism

- Etienne Gilson, Jacques Maritain, G.E.M. Anscombe, and Alasdair MacIntyre (all recent Thomists)

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 Philip Schaff, The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House, 1953), vol. XI, The New Schaff-Herzog, Calvin College. Retrieved November 12, 2007.

- ↑ Schaff, The New Schaff-Herzog, Calvin College. Christian Classics Ethereal Library. Retrieved November 12, 2007.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Daniel Kennedy, "Aquinas, Thomas," Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th ed., [1] NewAdvent.org. (1912). Retrieved November 17, 2007.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Religious Encyclopedia, Christian Classics Ethereal Library. Retrieved November 12, 2007.

- ↑ G.K. Chesterton. Saint Thomas Aquinas: The Dumb Ox. (Image, [1933] 1974. ISBN 0385090021)

- ↑ Fr. Placid Conway, O.P., Saint Thomas Aquinas (London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1911), HIS STUDIES AT COLOGNE AND PARIS., Jacques Maritain Center. Retrieved November 12, 2007.

- ↑ Will Durant, The Age of Faith (Simon and Schuster, 1950), 978.

- ↑ R. E. A. Shanab, 1974. "Ghazali and Aquinason Causation." The Monist: The International Quarterly Journal of General Philosophical Inquiry 58(1): 140

- ↑ "Whether without grace man can know any truth?" Summa Theologica. First Part of the Second Part, Question 109. Christian Classics Ethereal Library. Retrieved 26 August 2006.

- ↑ R. C. Sproul, Renewing Your Mind: Basic Christian Beliefs You Need to Know. (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 1998), 33

- ↑ Norman L. Geisler (ed). Baker Encyclopedia of Christian Apologetics. (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 1999), 726

- ↑ Geisler, 727.

- ↑ Whether human virtue is a habit? Summa, Q55a1.. Christian Classics Ethereal Library. Retrieved November 12, 2007.

- ↑ Summa, Q62a2. Christian Classics Ethereal Library. Retrieved November 4, 2007.

- ↑ Louis Pojman, Ethics (Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Company, 1995).

- ↑ Whether the natural law contains several precepts, or only one? Summa, Q94a2. Christian Classics Ethereal Library. Retrieved November 4, 2007.

- ↑ Peter Singer, "Animals" in The Oxford Companion to Philosophy. Retrieved November 12, 2007.

- ↑ Peter Kreeft, Summa of the Summa (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1990), 74-77, 86-87, 97-99, 105, 111-112.

- ↑ Aquinas, Thomas, Jewish Encyclopedia. Retrieved November 12, 2007.

- ↑ Aidan Nichols. Discovering Aquinas. (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2002), 173-174

- ↑ Thomas Aquinas, Aquinas's Shorter Summa (Manchester, NH: Sophia Institute Press, 2002), 228-229

- ↑ Aquinas 2002, 231-239.

- ↑ Aquinas 2002, 241, 245-249. Emphasis is the author's.

- ↑ Kreeft, 383.

- ↑ Umberto Eco, and James V. Wertsch. The Aesthetics of Thomas Aquinas, revised ed. (Santa Fe, NM: Radius Books, 1989. ISBN 0091823595)

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Adler, Mortimer J. (Ed.) "Bibliography of Additional Readings." In Great Books of the Western World, 2nd ed., v. 2, 987-988. Chicago: Encyclopedia Britannica, 1990.

- Aquinas, Thomas. Aquinas's Shorter Summa. Manchester, NH: Sophia Institute Press, 2002. ASIN: B001B190D0

- Aquinas, Thomas, Saint. On the truth of the Catholic faith. Summa contra Gentiles. Garden City, NY: Image Books, 1955-1957.

- Aquinas, Thomas; and Anton Charles Pegis. Basic writings of Saint Thomas Aquinas …. New York: Random House, 1945.

- Aquinas, Thomas. Summa of the Summa. Ignatius Press, 1990. in English. ISBN 089870300X

- Aquinas, Thomas Saint; and Daniel J. Sullivan; Dominicans. The Summa theologica. Chicago: Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1955.

- Boland, Vivian. St Thomas Aquinas: Continuum Library of Educational Thought. Continuum, 2007. ISBN 082648400X.

- Carroll, James. Constantine's sword: the church and the Jews: a history. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2001. ISBN 0395779278

- Chesterton, G.K. Saint Thomas Aquinas: The Dumb Ox. Image, (original 1933) 1974. ISBN 0385090021

- Copleston, F.C. Aquinas. Penguin, 1955.

- Copleston, Frederick Charles. Thomas Aquinas. London: Search Press ; New York: Barnes and Noble, 1976. ISBN 9780064912778

- Durant, Will. The Age of Faith. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1950.

- Eco, Umberto, and James V. Wertsch. The Aesthetics of Thomas Aquinas, rev. ed. Santa Fe, NM: Radius Books, 1989. ISBN 0091823595

- Geisler, Norman L., ed. Baker Encyclopedia of Christian Apologetics. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 1999. ISBN 0801021510

- Kreeft, Peter J. A Shorter Summa: The Essential Philosophical Passages of Saint Thomas Aquinas' Summa Theologica. (translated from the Latin) Ignatius Press, 1993. ISBN 0898704383

- McInerny, Ralph M. St. Thomas Aquinas. Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1977. ISBN 0805762485

- Nichols, Aidan. Discovering Aquinas: An Introduction to His Life, Work, and Influence. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2002. ISBN 0802805140

- O'Meara, Thomas F. Thomas Aquinas theologian. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1997. ISBN 0268018987

- Paterson, Craig, & Matthew S. Pugh (eds.). Analytical Thomism: Traditions in Dialogue. Ashgate, 2006. Introduction to Thomism. Retrieved November 17, 2007.

- Pojman, Louis. Ethics, fifth ed. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Company, [1995] 2005. ISBN 0534619363

- Shanab, R.E.A., 1974. "Ghazali and Aquinason Causation." The Monist: The International Quarterly Journal of General Philosophical Inquiry 58(1): 140

- Sproul, R.C. Renewing Your Mind: Basic Christian Beliefs You Need to Know, third ed. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 1998. ISBN 0801058155

- Torrell, Jean-Pierre. Saint Thomas Aquinas. Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press, 2003. ISBN 0813208521

External links

By Aquinas

All links retrieved April 30, 2023.

- Summa Theologica.

- On Being and Essence (De Ente et Essentia).

- Catena Aurea (partial).

- Corpus Thomisticum - the works of St. Thomas Aquinas (Latin).

- Works by Thomas Aquinas. Project Gutenberg.

- Bibliotheca Thomistica IntraText: texts, concordances and frequency lists.

- St Thomas' Multilanguage Opera Omnia.

About Aquinas

- Biography of Aquinas by G. K. Chesterton (Warning: protected by copyright outside of Australia).

- Aquinas on Intelligent Extra-Terrestrial Life.

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry.

- Aquinas's Moral, Political and Legal Philosophy.

- Thomistica.net news and newsletter devoted to the academic study of Thomas Aquinas.

General Philosophy Sources

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Paideia Project Online.

- Project Gutenberg.

| |||||

| This article is part of the Doctors of the Church series |

|

St. Gregory the Great | St.Ambrose | St. Augustine | St. Jerome | St. John Chrysostom | St. Basil | St. Gregory Nazianzus | St. Athanasius | St. Thomas Aquinas | St. Bonaventure | St. Anselm | St. Isidore | St. Peter Chrysologus | St. Leo the Great | St. Peter Damian | St. Bernard | St. Hilary of Poitiers | St. Alphonsus Liguori | St. Francis de Sales | St. Cyril of Alexandria | St. Cyril of Jerusalem | St. John Damascene | St. Bede the Venerable | St. Ephrem | St. Peter Canisius | St. John of the Cross | St. Robert Bellarmine | St. Albertus Magnus | St. Anthony of Padua | St. Lawrence of Brindisi | St. Teresa of Avila | St. Catherine of Siena | St. Thérèse of Lisieux |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.