Japanese art

| Art history |

| Eastern art history |

| Japanese art history |

| General |

|

Japanese Art Main Page |

| Historical Periods |

|

Jōmon and Yayoi periods |

| Japanese Artists |

|

Artists (chronological) |

| Schools, Styles and Movements |

|

Schools category |

| The Art World |

|

Art museums |

| Anime and Manga |

|

Anime -

Manga -

Animators |

| Japan WikiProject |

Japanese art covers a wide range of art styles and media, including ancient pottery, sculpture in wood and bronze, ink painting on silk and paper, calligraphy, ceramics, architecture, oil painting, literature, drama and music. The history of Japanese art begins with the production of ceramics by early inhabitants sometime in the tenth millennium B.C.E. The earliest complex art is associated with the spread of Buddhism in the seventh and eighth centuries C.E. The arts in Japan were patronized and sustained for centuries by a series of imperial courts and aristocratic clans, until urbanization and industrialization created a popular market for art. Both religious and secular artistic traditions developed, but even the secular art was imbued with Buddhist and Confucian aesthetic principles, particularly the Zen concept that every aspect of the material world is part of an all-encompassing whole.

Over its long history, Japanese art absorbed many foreign artistic traditions and carried on intermittent exchanges with China and Korea. When Japan came into contact with the Western world during the nineteenth century, Japanese woodblock prints, paintings and ceramics had a considerable influence on European art, particularly on cubism and impressionism. Japanese aesthetic principles of simplicity and understatement influenced Western architecture and design during the twentieth century. Japanese artists also absorbed Western techniques and materials and gained international audiences. Contemporary Japanese art is concerned with themes such as self-identity and finding fulfillment in a world dominated by technology. Since the 1990s, Japanese animation, known as anime, has become widely popular with young people in the West.

| This article contains Japanese text. Without proper rendering support, you may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols instead of kanji and kana. |

Overview

Historically, Japan has been subject to sudden introductions of new and alien ideas followed by long periods of minimal contact with the outside world during which foreign elements were assimilated, adapted to Japanese aesthetic preferences, and sometimes developed into new forms.

Like China and Korea, Japan developed both religious and secular artistic traditions. The earliest complex art in Japan was produced in the seventh and eighth centuries C.E. in connection with Buddhism. In the ninth century, as the Japanese began to turn away from China, and indigenous forms of expression were developed, the secular arts became increasingly important. A social and intellectual elite refined ink painting, calligraphy, poetry, literature and music as forms of self-expression and entertainment. Until the late fifteenth century, both religious and secular arts flourished. After the Ōnin War (1467-1477), Japan entered a period of political, social, and economic disruption that lasted for over a century. In the state that emerged under the leadership of the Tokugawa shogunate, organized religion played a much less important role in people's lives, and the arts that became primarily secular. The Japanese, in this period, found sculpture a much less sympathetic medium for artistic expression; most Japanese sculpture is associated with religion, and the medium's use declined with the lessening importance of traditional Buddhism.

During the sixteenth century, the emergence of a wealthy merchant class and urban areas centered around industries such as the production of textiles created a demand for popular entertainment and for mass-produced art such as wood block prints and picture books. In the Edo period (1603 – 1868), a style of woodblock prints called ukiyo-e became an important art form, used to produce colorfully printed post cards, theater programs, news bulletins and text books.

Painting is the preferred artistic expression in Japan, practiced by amateurs and professionals alike. Ink and water color painting were an outgrowth of calligraphy; until modern times, the Japanese wrote with a brush rather than a pen. Oil painting was introduced when Japan came into contact with the West during the sixteenth century, along with Western aesthetic concepts such as the use of perspective in landscapes. Contemporary Japanese painters work in all genres including traditional ink and water color painting, classical oil painting, and modern media.

Japanese ceramics are among the finest in the world and include the earliest known artifacts of Japanese culture. In architecture, Japanese preferences for natural materials and an interaction of interior and exterior space are clearly expressed.

Japan's contributions to contemporary art, fashion and architecture, are creations of a modern, global, and multi-cultural (or acultural) bent.

History of Japanese art

Jōmon art

The first settlers of Japan, the Jōmon people (c 11,000?–c 300 B.C.E.), named for the cord markings that decorated the surfaces of their clay vessels, were nomadic hunter-gatherers who later practiced organized farming and built cities with substantial populations. They built simple houses of wood and thatch set into shallow earthen pits to provide warmth from the soil, and crafted lavishly decorated pottery storage vessels, clay figurines called dogu, and crystal jewels.

Yayoi art

The Yayoi people, named for the district in Tokyo where remnants of their settlements first were found, arrived in Japan about 350 B.C.E., bringing their knowledge of wetland rice cultivation, the manufacture of copper weapons and bronze bells (dōtaku), and wheel-thrown, kiln-fired ceramics. Dōtaku (|銅鐸), smelted from relatively thin bronze and richly decorated, were probably used only for rituals. The oldest dōtaku found date from the second or third century B.C.E. (corresponding to the end of the Yayoi era). Historians believe that dōtaku were used to pray for good harvests because they are decorated with animals such as the dragonfly, praying mantis and spider, that are natural enemies of insect pests that attack paddy fields.

Kofun art

The third stage in Japanese prehistory, the Kofun, or Tumulus, period (ca. 250–552 C.E.), (named for the tombs) represents a modification of Yayoi culture, attributable either to internal development or external force. In this period, diverse groups of people formed political alliances and coalesced into a nation. Typical artifacts are bronze mirrors, symbols of political alliances, and clay sculptures called haniwa which were erected outside tombs.

Asuka and Nara art

During the Asuka and Nara periods, so named because the seat of Japanese government was located in the Asuka Valley from 552 to 710 and in the city of Nara until 784, the first significant introduction of Asian continental culture took place in Japan.

The transmission of Buddhism provided the initial impetus for contacts between China, Korea and Japan. The earliest Japanese sculptures of the Buddha are dated to the sixth and seventh century. In 538, the ruling monarch of Baekche, King Sông, sent an official diplomatic mission to formally introduce Buddhism to the Japanese court, and presented Buddhist images and sutras to the emperor.[1]

During the second half of the sixth century, Korean priests played an important role in the propagation of Buddhism, and the influence of Korean sculptors can be traced in Buddhist works of the Asuka period (538–710) from the Nara area.[2] After defeating the anti-Buddhist Mononobe and Nakatomi Clans in a battle in 587, the leader of the Soga Clan, Soga no Umako, ordered the construction of the first full scale Buddhist monastery in Japan, the Asuka-dera. An entry from the year 588 in the Nihon Shoki, a Japanese historical chronology, describes the numerous craftsmen who came from Baekche to Japan to supervise work on the Asuka-dera.[3]

During this period the Japanese adapted other foreign concepts and practices which had a profound effect on Japanese culture, including the use of Chinese written language; historiography; complex theories of centralized government with an effective bureaucracy; the use of coins; and the standardization of weights and measures. New technologies, new building techniques, more advanced methods of casting in bronze, and new techniques and media for painting brought about innovations in Japanese art.

Horyu-ji

The earliest Buddhist structures still extant in Japan, and the oldest wooden buildings in the Far East are found at the Hōryū-ji to the southwest of Nara. First built in the early seventh century as the private temple of Crown Prince Shotoku, it consists of 41 independent buildings. The most important ones, the main worship hall, or Kondo (Golden Hall), and Goju-no-to (Five-story Pagoda), stand in the center of an open area surrounded by a roofed cloister. The Kondo, in the style of Chinese worship halls, is a two-story structure of post-and-beam construction, capped by an irimoya, or hipped-gabled roof of ceramic tiles.

Inside the Kondo, on a large rectangular platform, are some of the most important sculptures of the period. The central image is a Shaka Trinity (623), the historical Buddha flanked by two bodhisattvas, sculpture cast in bronze by the sculptor Tori Busshi (flourished early seventh century) in homage to the recently deceased Prince Shotoku. At the four corners of the platform are the Guardian Kings of the Four Directions, carved in wood around 650. Also housed at Hōryū-ji is the Tamamushi Shrine, a wooden replica of a Kondo, which is set on a high wooden base that is decorated with figural paintings executed in a medium of mineral pigments mixed with lacquer.

Pagoda and Kondo at Horyu-ji, eighth century

The Pagoda has certain characteristics unique to Hōryū-ji

Replica of Kudara Kannon in the British Museum, Hōryū-ji, late seventh century

Tōdai-ji

Constructed in the eighth century as the headquarters for a network of temples in each of the provinces, the Tōdai-ji in Nara is the most ambitious religious complex erected in the early centuries of Buddhist worship in Japan. Appropriately, the 16.2-m (53-ft) Buddha (completed 752) enshrined in the main Buddha hall, or Daibutsuden, is a Rushana Buddha, the figure that represents the essence of Buddhahood, just as the Tōdaiji represented the center for Imperially sponsored Buddhism and its dissemination throughout Japan. Only a few fragments of the original statue survive, and the present hall and central Buddha are reconstructions from the Edo period.

Clustered around the Daibutsuden on a gently sloping hillside are a number of secondary halls: the Hokkedo (Lotus Sutra Hall), with its principal image, the Fukukenjaku Kannon (the most popular bodhisattva), crafted of dry lacquer (cloth dipped in lacquer and shaped over a wooden armature); the Kaidanin (Ordination Hall) with its magnificent clay statues of the Four Guardian Kings; and the storehouse, called the Shosoin. This last structure is of great importance as a historical cache, because contains the utensils that were used in the temple's dedication ceremony in 752, the eye-opening ritual for the Rushana image, as well as government documents and many secular objects owned by the Imperial family.

Tōdai-ji: Openwork playing flute Bodisatva in Octagonal Lantern Tower, eighth century

Heian art

In 794 the capital of Japan was officially transferred to Heian-kyo (present-day Kyoto), where it remained until 1868. The term Heian period refers to the years between 794 and 1185, when the Kamakura shogunate was established at the end of the Genpei War. The period is further divided into the early Heian and the late Heian, or Fujiwara era, which began in 894, the year imperial embassies to China were officially discontinued.

Early Heian art: In reaction to the growing wealth and power of organized Buddhism in Nara, the priest Kūkai (best known by his posthumous title Kōbō Daishi, 774-835) journeyed to China to study Shingon, a form of Vajrayana Buddhism, which he introduced into Japan in 806. At the core of Shingon worship are mandalas, diagrams of the spiritual universe, which began to influence temple design. Japanese Buddhist architecture also adopted the stupa, originally an Indian architectural form, in the style of a Chinese-style pagoda.

The temples erected for this new sect were built in the mountains, far away from the Court and the laity in the capital. The irregular topography of these sites forced Japanese architects to rethink the problems of temple construction, and in so doing to choose more indigenous elements of design. Cypress-bark roofs replaced those of ceramic tile, wood planks were used instead of earthen floors, and a separate worship area for the laity was added in front of the main sanctuary.

The temple that best reflects the spirit of early Heian Shingon temples is the Muro-ji (early ninth century), set deep in a stand of cypress trees on a mountain southeast of Nara. The wooden image (also early 9th c.) of Shakyamuni, the "historic" Buddha, enshrined in a secondary building at the Muro-ji, is typical of the early Heian sculpture, with its ponderous body, covered by thick drapery folds carved in the hompa-shiki (rolling-wave) style, and its austere, withdrawn facial expression.

Fujiwara art: In the Fujiwara period, Pure Land Buddhism, which offered easy salvation through belief in Amida (the Buddha of the Western Paradise), became popular. This period is named after the Fujiwara family, then the most powerful in the country, who ruled as regents for the Emperor, becoming, in effect, civil dictators. Concurrently, the Kyoto nobility developed a society devoted to elegant aesthetic pursuits. So secure and beautiful was their world that they could not conceive of Paradise as being much different. They created a new form of Buddha hall, the Amida hall, which blends the secular with the religious, and houses one or more Buddha images within a structure resembling the mansions of the nobility.

The Ho-o-do (Phoenix Hall, completed 1053) of the Byodoin, a temple in Uji to the southeast of Kyoto, is the exemplar of Fujiwara Amida halls. It consists of a main rectangular structure flanked by two L-shaped wing corridors and a tail corridor, set at the edge of a large artificial pond. Inside, a single golden image of Amida (c. 1053) is installed on a high platform. The Amida sculpture was executed by Jocho, who used a new canon of proportions and a new technique (yosegi), in which multiple pieces of wood are carved out like shells and joined from the inside. Applied to the walls of the hall are small relief carvings of celestials, the host believed to have accompanied Amida when he descended from the Western Paradise to gather the souls of believers at the moment of death and transport them in lotus blossoms to Paradise. Raigō (来迎, "welcoming approach") paintings and sculptures, depicting Amida Buddha descending on a purple cloud at the time of a person’s death, became very popular among the upper classes.Raigo paintings on the wooden doors of the Ho-o-do, depicting the Descent of the Amida Buddha, are an early example of Yamato-e, Japanese-style painting, and contain representations of the scenery around Kyoto.

E-maki: In the last century of the Heian period, the horizontal, illustrated narrative handscroll, the e-maki, became well-established. Dating from about 1130, the illustrated 'Tale of Genji' represents one of the high points of Japanese painting. Written about the year 1000 by Murasaki Shikibu, a lady-in-waiting to the Empress Akiko, the novel deals with the life and loves of Genji and the world of the Heian court after his death. The twelfth-century artists of the e-maki version devised a system of pictorial conventions that visually convey the emotional content of each scene. In the second half of the century, a different, livelier style of continuous narrative illustration became popular. The Ban Dainagon Ekotoba (late twelfth century), a scroll that deals with an intrigue at court, emphasizes figures in active motion depicted in rapidly executed brush strokes and thin but vibrant colors.

E-maki also serve as some of the earliest and greatest examples of the otoko-e (Men's pictures) and onna-e (Women's pictures) styles of painting. Of the many fine differences in the two styles intended to appeal to the aesthetic preferences of each gender, the most easily noticeable are the differences in subject matter. Onna-e, epitomized by the Tale of Genji handscroll, typically dealt with court life, particularly the court ladies, and with romantic themes. Otoko-e, on the other hand, often recorded historical events, particularly battles. The Siege of the Sanjō Palace (1160), depicted in the painting "Night Attack on the Sanjō Palace" is a famous example of this style.

Heian literature: The term “classical Japanese literature” is generally applied to literature produced during the Heian Period.

The Tale of Genji is considered the pre-eminent masterpiece of Heian fiction and an early example of a work of fiction in the form of a novel. Other important works of this period include the Kokin Wakashū (905, Waka Poetry Anthology) and The Pillow Book (990s), an essay about the life, loves, and pastimes of nobles in the Emperor's court written by Sei Shonagon. The iroha poem, now one of two standard orderings for the Japanese syllabary, was also written during the early part of this period. During this time, the imperial court patronized poets, many of whom were courtiers or ladies-in-waiting, and editing anthologies of poetry was a national pastime. Reflecting the aristocratic atmosphere, the poetry was elegant and sophisticated and expressed emotions in a rhetorical style.

Kamakura art

In 1180 a war broke out between the two most powerful warrior clans, the Taira and the Minamoto; five years later the Minamoto emerged victorious and established a de facto seat of government at the seaside village of Kamakura, where it remained until 1333. With the shift of power from the nobility to the warrior class, the arts had a new audience: men devoted to the skills of warfare, priests committed to making Buddhism available to illiterate commoners, and conservatives, the nobility and some members of the priesthood who regretted the declining power of the court. Thus, realism, a popularizing trend, and a classical revival characterize the art of the Kamakura period.

Sculpture: The Kei school of sculptors, particularly Unkei, created a new, more realistic style of sculpture. The two Niō guardian images (1203) in the Great South Gate of the Tōdai-ji in Nara illustrate Unkei's dynamic suprarealistic style. The images, about 8 m (about 26 ft) tall, were carved of multiple blocks in a period of about three months, a feat indicative of a developed studio system of artisans working under the direction of a master sculptor. Unkei's polychromed wood sculptures (1208, Kōfuku-ji, Nara) of two Indian sages, Muchaku and Seshin, the legendary founders of the Hosso sect, are among the most accomplished realistic works of the period.

Calligraphy and painting: The Kegon Engi Emaki, the illustrated history of the founding of the Kegon sect, is an excellent example of the popularizing trend in Kamakura painting. The Kegon sect, one of the most important in the Nara period, fell on hard times during the ascendancy of the Pure Land sects. After the Genpei War (1180-1185), Priest Myōe of Kōzan-ji temple sought to revive the sect and also to provide a refuge for women widowed by the war. The wives of samurai had been discouraged from learning more than a syllabary system for transcribing sounds and ideas (see kana), and most were incapable of reading texts that employed Chinese ideographs (kanji). The Kegon Engi Emaki combines passages of text, written in easily readable syllables, and illustrations with the dialog between characters written next to the speakers, a technique comparable to contemporary comic strips. The plot of the e-maki, the lives of the two Korean priests who founded the Kegon sect, is swiftly paced and filled with fantastic feats such as a journey to the palace of the Ocean King, and a poignant love story.

A more conservative work is the illustrated version of Murasaki Shikibu's diary. E-maki versions of her novel continued to be produced, but the nobility, attuned to the new interest in realism yet nostalgic for past days of wealth and power, revived and illustrated the diary in order to recapture the splendor of the author's times. One of the most beautiful passages illustrates the episode in which Murasaki Shikibu is playfully held prisoner in her room by two young courtiers, while, just outside, moonlight gleams on the mossy banks of a rivulet in the imperial garden.

Muromachi art

During the Muromachi period (1338-1573), also called the Ashikaga period, a profound change took place in Japanese culture. The Ashikaga clan took control of the shogunate and moved its headquarters back to Kyoto, to the Muromachi district of the city. With the return of government to the capital, the popularizing trends of the Kamakura period came to an end, and cultural expression took on a more aristocratic, elitist character. Zen Buddhism, the Ch'an sect traditionally thought to have been founded in China in the sixth century C.E., was introduced for a second time into Japan and took root.

Painting: Because of secular ventures and trading missions to China organized by Zen temples, many Chinese paintings and objects of art were imported into Japan and profoundly influenced Japanese artists working for Zen temples and the shogunate. Not only did these imports change the subject matter of painting, but they also modified the use of color; the bright colors of Yamato-e yielded to the monochromes of painting in the Chinese manner, where paintings are generally only in black and white or different tones of a single color.

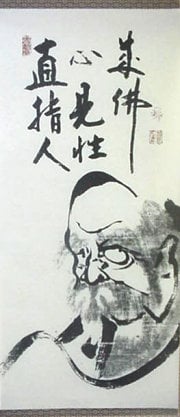

Typical of early Muromachi painting is the depiction by the priest-painter Kao (active early fifteenth century) of the legendary monk Kensu (Hsien-tzu in Chinese) at the moment he achieved enlightenment. This type of painting was executed with quick brush strokes and a minimum of detail. Catching a Catfish with a Gourd (early fifteenth century, Taizo-in, Myoshin-ji, Kyoto), by the priest-painter Josetsu (active c. 1400), marks a turning point in Muromachi painting. Executed originally for a low-standing screen, it has been remounted as a hanging scroll with inscriptions by contemporary figures above, one of which refers to the painting as being in the "new style." In the foreground a man is depicted on the bank of a stream holding a small gourd and looking at a large slithery catfish. Mist fills the middle ground, and the background mountains appear to be far in the distance. It is generally assumed that the "new style" of the painting, executed about 1413, refers to a more Chinese sense of deep space within the picture plane.

The foremost artists of the Muromachi period are the priest-painters Shubun and Sesshu. Shubun, a monk at the Kyoto temple of Shokoku-ji, created in the painting Reading in a Bamboo Grove (1446) a realistic landscape with deep recession into space. Sesshu, unlike most artists of the period, was able to journey to China and study Chinese painting at its source. The Long Handscroll is one of Sesshu's most accomplished works, depicting a continuing landscape through the four seasons.

Azuchi-Momoyama art

In the Momoyama period (1573-1603), a succession of military leaders, including Oda Nobunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and Tokugawa Ieyasu, attempted to bring peace and political stability to Japan after an era of almost 100 years of warfare. Oda, a minor chieftain, acquired power sufficient to take de facto control of the government in 1568 and, five years later, to oust the last Ashikaga shogun. Hideyoshi took command after Oda's death, but his plans to establish hereditary rule were foiled by Ieyasu, who established the Tokugawa shogunate in 1603.

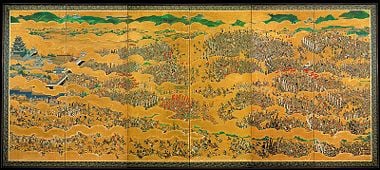

Painting: The most important school of painting in the Momoyama period was that of the Kanō school. Kanō painters often worked on a large scale, painting nature scenes of birds, plants, water, or other animals on sliding doors or screens, covering the background with gold leaf. The school is equally renowned for its monochrome ink-on-silk landscapes, flat pictures that balance impeccably detailed realistic depictions of animals and other subjects in the foreground with abstract, often entirely blank, clouds and other background elements. The greatest innovation of the period was the formula, developed by Kano Eitoku, for the creation of monumental landscapes on the sliding doors enclosing a room. The decoration of the main room facing the garden of the Juko-in, a subtemple of Daitoku-ji (a Zen temple in Kyoto), is perhaps the best extant example of Eitoku's work. A massive ume tree and twin pines are depicted on pairs of sliding screens in diagonally opposite corners, their trunks repeating the verticals of the corner posts and their branches extending to left and right, unifying the adjoining panels. Eitoku's screen, Chinese Lions, also in Kyoto, reveals the bold, brightly colored style of painting preferred by the samurai.

Hasegawa Tohaku, a contemporary of Eitoku, developed a somewhat different and more decorative style for large-scale screen paintings. In his Maple Screen, now in the temple of Chishaku-in, Kyoto, he placed the trunk of the tree in the center and extended the limbs nearly to the edge of the composition, creating a flatter, less architectonic work than Eitoku, but a visually gorgeous painting. His sixfold screen Pine Wood is a masterly rendering in monochrome ink of a grove of trees enveloped in mist.

Art of the Edo period

The Tokugawa shogunate of the Edo period gained undisputed control of the government in 1603 and was largely successful in bringing peace and economic and political stability to the country. The shogunate survived until 1867, when it was forced to capitulate because of its failure to deal with pressure from Western nations to open the country to foreign trade. One of the dominant themes in the Edo period was the repressive policies of the shogunate and the attempts of artists to escape these strictures. The foremost of these was the closing of the country to foreigners and the accoutrements of their cultures, and the imposition of strict codes of behavior affecting every aspect of life, including the clothes that could be worn, the choice of a marriage partner, and the activities that could be pursued by members of each social class.

In the early years of the Edo period, before the full impact of Tokugawa policies had been felt, some of Japan's finest expressions in architecture and painting were produced: Katsura Palace in Kyoto and the paintings of Tawaraya Sōtatsu, pioneer of the Rimpa school.

Architecture: Katsura Detached Palace, built in imitation of Genji's palace, contains a cluster of shoin buildings that combine elements of classic Japanese architecture with innovative restatements. The whole complex is surrounded by a beautiful garden with paths for walking.

Painting: The Rimpa (琳派), also romanized as Rinpa, one of the principal schools of Japanese decorative painting, was created by the calligrapher and designer Hon'ami Kōetsu (1558-1637) and the painter Tawaraya Sōtatsu (died c. 1643). Kōetsu’s painting style recalled the flamboyant aristocratic genre of the Heian period. Tawaraya Sōtatsu evolved a superb decorative style by re-creating themes from classical literature. Sōtatsu and Kōetsu collaborated to revive Yamato-e with contemporary innovations, creating richly embellished, intimate depictions of simple natural subjects like birds, plants and flowers, on a background of gold leaf. Many of these paintings were used on the sliding doors and walls (fusuma) of noble homes.

Sōtatsu popularized a technique called tarashikomi, which was carried out by dropping one color onto another while the first was still wet. He also developed an original style of monochrome painting, where the ink was used sensuously, as if it were color. Roughly 50 years later, the style was consolidated by brothers Ōgata Kōrin and Kenzan. The Rimpa school reached its peak during the Genroku period (1688-1704).

Spring Landscape, unknown Rimpa school painter, eighteenth century, six-screen ink and gold on paper.

Sculpture The Buddhist monk Enkū wandered all over Japan, carving 120,000 wooden statues of the Buddha in a rough, individual style. No two were alike. Many of the statues were crudely carved from tree stumps or scrap wood with a few strokes of a hatchet. Some were given to comfort those who had lost family members, others to guide the dying on their journeys to the afterlife. Thousands of these wooden statues remain today all over Japan, especially in Hida and Gifu.

Woodblock prints: The school of art best known in the West is that of the ukiyo-e ("floating world") paintings and woodblock prints of the demimonde, the world of the kabuki theater and the brothel district. Ukiyo-e prints began to be produced in the late seventeenth century, but the first polychrome print was produced by Harunobu in 1764. Print designers of the next generation, including Torii Kiyonaga and Utamaro, created elegant and sometimes insightful depictions of courtesans and geisha, with emphasis on their hair styles, makeup and fashion. Hokusai features scenic views such as his 36 views of Mount Fuji. In the nineteenth century the dominant figure was Hiroshige, a creator of romantic and somewhat sentimental landscape prints. The odd angles and shapes through which Hiroshige often viewed landscape, and the work of Kiyonaga and Utamaro, with its emphasis on flat planes and strong linear outlines, had a profound impact on such Western artists as Edgar Degas and Vincent van Gogh.

Bunjinga: Another school of painting contemporary with ukiyo-e was Nanga (南画, "Southern painting"), also known as Bunjinga (文人画, "literati painting"), a style based on paintings executed by Chinese scholar-painters. Bunjin artists considered themselves literati, or intellectuals, and shared an admiration for traditional Chinese culture. Their paintings, usually in monochrome black ink, sometimes with light color, and nearly always depicting Chinese landscapes or similar subjects, were patterned after Chinese literati painting, called wenrenhua (文人画) in Chinese. Since the Edo period policy of isolation (sakoku) restricted contact with China, the bunjin artists had access only to Chinese woodblock-printed painting manuals and an assortment of imported paintings ranging widely in quality. They developed their own unique form of painting, defined to a great extent by its rejection of other major Japanese schools of art, such as the Kano school and Tosa school. Bunjinga paintings almost always depicted traditional Chinese subjects such as landscapes and birds and flowers, and poetry or other inscriptions were also an important element.

Unlike other schools of art in which the founders passed on a specific style to their students or followers, nanga concerned the individual painter’s attitude towards art and his love of Chinese culture. Every bunjin artist displayed unique elements in his creations, and many diverged greatly from the stylistic elements employed by their forebears and contemporaries. The exemplars of this style are Ike no Taiga, Yosa Buson, Tanomura Chikuden, and Yamamoto Baiitsu. As Japan became exposed to Western culture at the end of the Edo period, bunjin began to incorporate stylistic elements of Western art into their own, though they nearly always avoided Western subjects.

Meiji art

After 1867, when Emperor Meiji ascended the throne, the introduction of Western cultural values led to a dichotomy in Japanese art between traditional values and attempts to duplicate and assimilate a variety of new ideas. This division remained evident in the late twentieth century, although much synthesis had already occurred, and resulted in an international cultural atmosphere and ever-increasing innovation in contemporary Japanese art.

By the early twentieth century, European architectural forms had been introduced and their marriage with principles of traditional Japanese architecture produced notable buildings like the Tokyo Train Station and the National Diet Building.

Manga were first drawn in the Meiji period, influenced greatly by English and French political cartoons.

Painting: The first response of the Japanese to Western art forms was open acceptance, and in 1876 the Technological Art School was opened, employing Italian instructors to teach Western methods. The second response was a pendulum swing in the opposite direction spearheaded by art critics Okakura Kakuzo and the American Ernest Fenollosa, who encouraged Japanese artists to retain traditional themes and techniques while creating works more in keeping with contemporary taste. Out of these two poles of artistic theory developed Yōga (Western-style painting) and Nihonga (Japanese painting), categories that remain valid to the present day.

The impetus for reinvigorating traditional painting by developing a more modern Japanese style came largely from Okakura Tenshin and Ernest Fenollosa who attempted to combat Meiji Japan's infatuation with Western culture by emphasizing to the Japanese the importance and beauty of native Japanese traditional arts. These two men played important roles in developing the curricula at major art schools, and actively encouraged and patronized artists.

Nihonga (日本画) was not simply a continuation of older painting traditions. In comparison with Yamato-e the range of subjects was broadened, and stylistic and technical elements from several traditional schools, such as the Kano-ha, Rinpa and Maruyama Okyo were blended together. The distinctions that had existed among schools in the Edo period were minimized. In many cases Nihonga artists also adopted realistic Western painting techniques, such as perspective and shading.

Nihonga are typically executed on washi (Japanese paper) or silk, using brushes. The paintings can be either monochrome or polychrome. If monochrome, typically sumi (Chinese ink) made from soot mixed with a glue from fishbone or animal hide is used. If polychrome, the pigments are derived from natural ingredients: minerals, shells, corals, and even semi-precious stones like garnets or pearls. The raw materials are powdered into ten gradations from fine to sand grain textures and hide glue is used as fixative. In both cases, water is used in the mixture. In monochrome nihonga, ink tones are modulated to obtain a variety of shadings from near white, through grey tones to black. In polychrome nihonga, great emphasis is placed on the presence or absence of outlines; typically outlines are not used for depictions of birds or plants. Occasionally, washes and layering of pigments are used to provide contrasting effects, and even more occasionally, gold or silver leaf may also be incorporated into the painting.

Yōga (洋画) in its broadest sense encompasses oil painting, watercolors, pastels, ink sketches, lithography, etching and other techniques developed in western culture. In a more limited sense, Yōga is sometimes used specifically to refer to oil painting. Takahashi Yuichi, a student of English artist Charles Wirgman, is regarded by many as the first true Yōga painter.

In 1876, when the Kobu Bijutsu Gakko (Technical Art School) was established by the Meiji government, foreign advisors, such as the Italian artist Antonio Fontanesi, were hired by the government to teach Western techniques to Japanese artists, such as Asai Chu. In the 1880s, a general reaction against Westernization and the growth in popularity and strength of the Nihonga movement caused the temporary decline of Yōga. The Kobu Bijutsu Gakko was forced to close in 1883, and when the Tokyo Bijutsu Gakko (the forerunner of the Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music) was established in 1887, only Nihonga subjects were taught. However, in 1889, Yōga artists established the Meiji Bijutsukai (Meiji Fine Arts Society), and in 1893, the return of Kuroda Seiki from his studies in Europe gave fresh impetus to the Yōga genre. From 1896, a Yōga department was added to the curriculum of the Tokyo Bijutsu Gakko. Since that time, Yōga and Nihonga have been the two main divisions of modern Japanese painting, reflected in education, the mounting of exhibitions, and the identification of artists.

Postwar period

After World War II, many artists moved away from local artistic developments into international artistic traditions. But traditional Japanese conceptions endured, particularly in the use of modular space in architecture, certain spacing intervals in music and dance, a propensity for certain color combinations and characteristic literary forms. The wide variety of art forms available to the Japanese reflect the vigorous state of the arts, widely supported by the Japanese people and promoted by the government. In the 1950s and 1960s, Japan's artistic avant garde included the internationally influential Gutai group, an artistic movement and association of artists founded by Jiro Yoshihara and Shozo Shimamoto in 1954. The manifesto for the Gutai group, written by Yoshihara in 1956, expresses a fascination with the beauty that arises when things become damaged or decayed. The process of damage or destruction is celebrated as a way of revealing the inner "life" of a given material or object. The work of the Gutai group originated or anticipated various postwar genres such as performance art, installation art, conceptual art, and wearable art.

Contemporary art in Japan

Contemporary Japanese art takes many forms and expressions ranging from painting, drawing, sculpture, architecture, film and photography to advertisements, anime, and video games. The realities of life in modern Japan, which include intensely urbanized areas in which millions of people live in tiny spaces and have little contact with nature, and a vacuum caused by the gradual disappearance of traditional family structures and religious practices, have produced a new context for art, and a new set of artistic requirements and themes. Painters, sculptors, photographers and film makers strive to give meaning to daily existence, or simply to give expression to the conflicts and anxieties of modern life. Many attempt to reconcile traditional values with modern realities, and some draw from ancient artistic principles to bring beauty and fulfillment into modern urban life. Japanese designers, sculptors and architects are committed to creating living environments in which the public can experience some kind of spiritual satisfaction, or re-connect with nature in the midst of the city.

Artists continue to paint in the traditional manner, with black ink and color on paper or silk. Some depict traditional subject matter, while others use traditional media to explore new and different motifs and styles. Other painters work in oil and eschew traditional styles. Japan’s rapid technological and economic advancement have provided artists with an endless supply of new media and new concepts, and with the financial resources to develop them. Contemporary Japanese artists have a worldwide audience. Japanese artists also excel in the fields of graphic design, commercial art (billboards, magazine advertisements), and in video game graphics and concept art.

Anime (アニメ), or Japanese animation, first appeared around 1917,[4] inspired by cartoons imported from America. During the 1930s, Osamu Tezuka adapted and simplified Disney animation techniques to allow him to produce animated films on a tight schedule with inexperienced staff. Animated films Anime and television shows experienced a surge of popularity in Japan during the 1980s and adaptations for Western audiences became highly successful in the 1990s. Anime studios abound in Japan. Among the best known anime artists are Hayao Miyazaki and the artists and animators of his Studio Ghibli.

Superflat, a self-proclaimed postmodern art movement influenced by manga and anime[5], is characterized by flat planes of color and graphic images involving a character style derived from anime and manga. It was founded by the artist Takashi Murakami, who uses the term “superflat” to refer to various flattened forms in Japanese graphic art, animation, pop culture and fine arts, as well as the "shallow emptiness of Japanese consumer culture."[6] Superflat blends art with commerce, packaging and selling art in the form of paintings, sculptures, videos, T-shirts, key chains, mouse pads, plush dolls, cell phone caddies, and designs for well-known brand names. Artists whose work is considered “Superflat” include Chiho Aoshima, Mahomi Kunikata, Yoshitomo Nara, Aya Takano, and Koji Morimoto.

Performing arts

A remarkable number of the traditional forms of Japanese music, dance, and theater have survived in the contemporary world, enjoying some popularity through identification with Japanese cultural values. Traditional music and dance, which trace their origins to ancient religious use - Buddhist, Shintō, and folk - have been preserved in the dramatic performances of Noh, Kabuki, and bunraku theater.

Ancient court music and dance forms deriving from continental sources were preserved through Imperial household musicians and temple and shrine troupes. Some of the oldest musical instruments in the world have been in continuous use in Japan from the Jōmon period, as shown by finds of stone and clay flutes and zithers having between two and four strings, to which Yayoi period metal bells and gongs were added to create early musical ensembles. By the early historical period (sixth to seventh centuries C.E.), there were a variety of large and small drums, gongs, chimes, flutes, and stringed instruments, such as the imported mandolin-like biwa and the flat six-stringed zither, which evolved into the thirteen-stringed koto. These instruments formed the orchestras for the seventh-century continentally derived ceremonial court music (gagaku), which, together with the accompanying bugaku (a type of court dance), are the most ancient of such forms still performed at the Imperial court, ancient temples, and shrines. Buddhism introduced the rhythmic chants, still used, that underpin shigin (a form of chanted poetry), and that were joined with native ideas to underlay the development of vocal music, such as in Noh.

Ceramics

Ceramics, one of Japan's oldest art forms, dates back to the Neolithic period (ca. 10,000 B.C.E.), when the earliest soft earthenware was coil-made, decorated by hand-impressed rope patterns (Jomon ware), and baked in the open. The pottery wheel was introduced in the third century B.C.E.. and in the third and fourth centuries C.E., a tunnel kiln in which stoneware, embellished with natural ash glaze, was fired at high temperatures. The production of stoneware was refined during the medieval period and continues today especially in central Honshu around the city of Seto. Korean potters brought to Japan after Toyotomi Hideyoshi's Korean campaigns in 1592 and 1597 introduced a variety of new techniques and styles and discovered the ingredients needed to produce porcelain in northern Kyushu.

The modern masters of these famous traditional kilns still employ the ancient formulas in pottery and porcelain, creating new techniques for glazing and decoration. Ancient porcelain kilns around Arita in Kyushu are still maintained by the lineage of the famous Sakaida Kakiemon XIV and Imaizume Imaiemon XIII, hereditary porcelain makers to the Nabeshima clan. In the old capital of Kyoto, the Raku family continues to produce the famous rough tea bowls that were made there in the sixteenth century. At Mino, the classic formulas of Momoyama-era Seto-type tea wares, such as the famous Oribe copper-green glaze and Shino ware's prized milky glaze, have been reconstructed. At the Kyoto and Tokyo arts universities, artist potters have experimented endlessly to recreate traditional porcelain and its decorations.

By the end of the 1980s, many master potters were making classic wares in various parts of Japan or in Tokyo, instead of working at major or ancient kilns. Some artists were engaged in reproducing famous Chinese styles of decoration or glazes, especially the blue-green celadon and the watery-green qingbai. One of the most beloved Chinese glazes in Japan is the chocolate-brown tenmoku glaze that covered the peasant tea bowls brought back from Southern Song China (in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries) by Zen monks. For their Japanese users, these chocolate-brown wares embodied the Zen aesthetic of wabi (rustic simplicity).

A folk movement in the 1920s by such master potters as Hamada Shoji and Kawai Kanjiro revived interest in the art of the village potter. These artists studied traditional glazing techniques to preserve native wares in danger of disappearing. The kilns at Tamba, overlooking Kobe, continued to produce the daily wares used in the Tokugawa period, while adding modern shapes. Most of the village wares were made anonymously by local potters for utilitarian purposes and local styles tended to be maintained without alteration. Kilns set up in Kyushu by Korean potters in the sixteenth century perpetuated sixteenth-century Korean peasant wares. In Okinawa, the production of village ware continued under several leading masters.[7]

Textiles

For centuries Japan has produced beautiful textiles decorated using a variety of techniques including resist-dyeing, tie-dyeing and embroidery. In early Confucian society, clothing was an important indicator of rank and social status. Members of the upper classes wore elaborately decorated clothing made of silk, while peasants wore clothing made of coarse homespun. During the Edo period, when urbanization and the rise of industry and a merchant class made textiles and clothing an even more important form of social identification. The motif, color and shape of a garment indicated an individual’s age, geographical origin, rank, gender, social, political and religious affiliation, and even occupation or association with a particular group. Textiles were also used for banners, doorway curtains (noren), and advertisements.

Tsujigahana (辻ヶ花) textiles, made using a stitched tie-dyed process enhanced with painting that developed during the Muromachi period (1336 – 1573), are considered to have reached the height of the Japanese textile arts. During the Edo (1603 to 1868) and succeeding Meiji period (1868 – 1912), textiles achieved a high degree of cultural distinction and artistic appreciation and evolved a greater range of artistic expression based on centuries-old traditions. Away from the palace workshops, weavers, dyers and needle workers added to local traditions by adapting foreign techniques, and revitalized existing patterns by absorbing exotic motifs and creating innovative designs. Elite classes commissioned complicated and diverse fabrics in silk brocades and filmy gauze weaves. The lower classes, remaining within strictly regulated feudal guidelines for material, patterns and colors, created new forms with bold images. Indigo dye was in common use. Dyeing emerged as an art form in its own right, and the use of brighter colors increased.[8]

A young woman wearing a kimono (Furisode).

Bonsai

Bonsai (盆栽, literally “tray-planted” or "potted plant") is the art of aesthetic miniaturization of trees by training them and growing them in containers. Bonsai are developed from seeds or cuttings, from young trees, or from naturally occurring stunted trees transplanted into containers. The trees are manipulated by pruning roots and branches, wiring and shaping, watering, and repotting in various styles of containers. The bonsai artist does not duplicate nature, but rather expresses a personal aesthetic philosophy by manipulating it. Japanese bonsai are meant to evoke the essential spirit of the plant being used. In all cases, they must look natural and never show the intervention of human hands.

The cultivation of bonsai, like other Japanese arts such as tea ceremony and flower arranging, is considered a form of Zen practice. The combination of natural elements with the controlling hand of humans evokes meditation on life and the mutability of all things. A bonsai artist seeks to create a triangular pattern which gives visual balance and expresses the relationship shared by a universal principle (life-giving energy, or deity), the artist, and the tree itself. According to tradition, three basic virtues, shin-zen-bi (standing for truth, goodness and beauty) are necessary to create a bonsai.[9]

The Japanese prize an aged appearance of the trunk and branches, and weathered-looking exposed upper roots, expressing the aesthetic concept of wabi-sabi, “nothing lasts, nothing is finished, and nothing is perfect.” There are several aesthetic principles which are for the most part unbroken, such as the rule that tree branches must never cross and trees should bow slightly forward, never lean back.[10]

Japanese gardens

Japanese gardens were originally modeled after the distinctive and stylized Chinese gardens. Ruins of gardens from the Asuka period (538-710) indicate that they were intended to reproduce the effect of the mountainous regions in China, expressing Buddhist and Daoist ideals. During the Heian period (794-1185), gardens became settings for ceremonies, amusement, and contemplation, and began to surround residences of the upper class. Japanese gardens are designed for a variety of purposes. Some gardens invite quiet contemplation, but may have also been intended for recreation, the display of rare plant specimens, or the exhibition of unusual rocks.

Typical Japanese gardens have a residence at their center from which the garden is viewed. In addition to residential architecture, Japanese gardens often contain several of these elements:

- Water, real or symbolic.

- Rocks.

- A lantern, typically of stone.

- A teahouse or pavilion.

- An enclosure device such as a hedge, fence, or wall of traditional character.

Karesansui gardens (枯山水) or "dry landscape” gardens were influenced by Zen Buddhism and can be found at Zen temples. No water is presents in Karesansui gardens; instead, raked gravel or sand simulates the feeling of water. The rocks used are chosen for their artistic shapes, and complemented with mosses and small shrubs. The rocks and moss represent ponds, islands, boats, seas, rivers, and mountains in an abstract landscape. Kanshoh-style gardens are designed to be viewed from a residence; pond gardens are intended for viewing from a boat; and strolling gardens (kaiyū-shiki), for viewing a sequence of effects from a path which circumnavigates the garden.

Aesthetic concepts

Japan's aesthetic conceptions, deriving from diverse cultural traditions, have been formative in the production of unique art forms. Over the centuries, a wide range of artistic motifs were refined and developed, becoming imbued with symbolic significance and acquiring many layers of meaning. Japanese aesthetic principles are significantly different from those of Western traditions. Shinto animism and the Buddhist perception that man and nature are one harmonious entity (ichi genron, monism) resulted in the concept that art is a natural expression of the essential relationship between the artist and the greater whole. Successful art is an expression of truth.

The media used for early art forms, ink and watercolor on silk or paper, required spontaneity and the training of the hand to produce brushstrokes effortlessly. These qualities, which originated with calligraphy, became essential to success in painting and the production of ceramics.

Art forms introduced from China were emulated and eventually adapted into unique Japanese styles. The monumental, symmetrically balanced, rational approach of Chinese art forms became miniaturized, irregular, and subtly suggestive in Japanese hands. The diagonal, reflecting a natural flow, rather than the fixed triangle, became the favored structural device, whether in painting, architectural or garden design, dance steps, or musical notations. Odd numbers replaced even numbers in the regularity of Chinese master patterns, and a pull to one side allowed a motif to turn the corner of a three-dimensional object, adding continuity and motion that was lacking in a static frontal design. By the twelfth century Japanese painters were using the cutoff, close-up, and fade-out in yamato-e scroll painting.

The Japanese had begun defining aesthetic ideas in a number of evocative phrases by the tenth or eleventh century. Shibui (|渋い) (adjective), or shibumi (渋み) (noun), refers to simple, subtle, and unobtrusive beauty, the essence of good taste. Wabi-sabi (侘寂), an aesthetic centered on the acceptance of transience, comes from two terms used to describe degrees of tranquility in Zen Buddhist meditative practices: (wabi), the repose found in humble melancholy, and (sabi), the serenity accompanying the enjoyment of subdued beauty. Characteristics of wabi-sabi include asymmetry, asperity, simplicity, modesty, intimacy, and suggestion of a natural process.[11] Wabi now connotes rustic simplicity, freshness or quietness, or understated elegance. Sabi is beauty or serenity that comes with age, when the life of the object and its impermanence are evidenced in its patina and wear, or in any visible repairs. Mono no aware (|物の哀れ, "the pathos of things") also translated as "an empathy toward things," is a Japanese term used to describe the awareness of mujo or the transience of things and a bittersweet sadness at their passing. The term was coined in the eighteenth century by the Edo-period Japanese cultural scholar Motoori Norinaga, to describe a central theme running through Japanese literature and art.

Zen thought also contributed the use of the unexpected to jolt the observer’s consciousness toward the goal of enlightenment. In art, this approach was expressed in combinations of such unlikely materials as lead inlaid in lacquer and in clashing poetic imagery. Unexpectedly humorous and sometimes grotesque images and motifs also stem from the Zen koan (conundrum). Miniature Zen rock gardens, diminutive plants (bonsai), and ikebana (flower arrangements), in which a few selected elements represented a garden, were the favorite pursuits of refined aristocrats for a millennium, and have remained a part of contemporary cultural life.

In Japanese aesthetics, suggestion is used rather than direct statement; oblique poetic hints and allusive and inconclusive melodies and thoughts are appreciated subconsciously, and their deeper symbolisms are understood by the trained eye and ear.

Japanese art is characterized by unique contrasts. In the ceramics of the prehistoric periods, for example, exuberance was followed by disciplined and refined artistry. The flamboyance of folk music and dance was a direct contrast to the self-restrained dignity and elegance of court music. Another example is two sixteenth-century structures: the Katsura Detached Palace is an exercise in simplicity, with an emphasis on natural materials, rough and untrimmed, and an affinity for beauty achieved by accident; Nikkō Tōshō-gū is a rigidly symmetrical structure replete with brightly colored relief carvings covering every visible surface.

Influence on other artistic traditions

Japanese art, valued not only for its simplicity but also for its colorful exuberance, considerably influenced nineteenth-century Western painting. Ukiyo-e woodcut prints reached Europe in the mid-nineteenth century where they became a source of inspiration for cubism and for many impressionist painters, such as Vincent van Gogh, Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Gustav Klimt. This movement was called Japonism. Especially influential were the works of Katsshika Hokusai and of Kitagawa Utamaro, with his use of partial views and emphasis on light and shade. Japanese aesthetic principles of simplicity and understatement had an impact on Western art and design during the twentieth century.

Japanese architecture influenced twentieth century Western architecture with its emphasis on simplicity, horizontal lines, and flexible spaces. American architect Frank Lloyd Wright was strongly influenced by Japanese spatial arrangements and the concept of interpenetrating exterior and interior space, long achieved in Japan by using walls made of sliding doors that opened onto covered verandas and gardens. Japanese filmmakers such as Akira Kurosawa, Kenji Mizoguchi, and Yasujiro Ozu won international acclaim and influenced Western cinematography with their use of natural beauty and symbolism, their attention to detail, original techniques, and the artistic composition of even the most mundane shots.

Since the 1990s, Japanese animation has become widely popular in the West, stimulating young artists to develop their own anime art, and becoming part of the daily television fare of millions of young children.

Social position of artists

Traditionally, the artist was a vehicle for expression and was personally reticent, in keeping with the role of an artisan or entertainer of low social status. There was often a distinction between professional artists employed by the court and amateur artists of the educated aristocracy who produced literature, poetry and paintings as a form of self-expression. Calligraphers were typically members of the Confucian literati class, or noble samurai class. At court, both men and women participated in poetry-writing contests. During the Heian period, women produced literature concerning life at court, while men were commissioned to write histories and chronologies, and to compile anthologies.

During the Kamakura period, artists of great genius were often recognized by feudal lords who bestowed names on them, allowing them to rise socially. The performing arts, however, were generally held in less esteem. The purported immorality of actresses of the early Kabuki theater caused the Tokugawa government to bar women from the stage; female roles in Kabuki and Noh thereafter were played by men.

After World War II, Japanese artists typically gathered in arts associations, some of which were long-established professional societies while others reflected the latest arts movements. The Japan Artists League was responsible for the largest number of major exhibitions, including the prestigious annual Nitten (Japan Art Exhibition). The P.E.N. Club of Japan (P.E.N. stands for prose, essay, and narrative), a branch of an international writers' organization, was the largest of some 30 major authors' associations. Actors, dancers, musicians, and other performing artists boasted their own societies, including the Kabuki Society, organized in 1987 to maintain kabuki’s traditional high standards, which were thought to be endangered by modern innovation. By the 1980s, however, avant-garde painters and sculptors had eschewed all groups and were "unattached" artists.

Art schools

There are a number of specialized universities for the arts in Japan, led by the national universities. The most important is the Tokyo Arts University, one of the most difficult of all national universities to enter. Another seminal center is Tama Arts University in Tokyo, which produced many of Japan's innovative young artists duing the late twentieth century. Traditional apprenticeship training in the arts remains, in which experts teach at their homes or schools within a master-pupil relationship. A pupil does not experiment with a personal style until achieving the highest level of training, or graduating from an arts school, or becoming head of a school. Many young artists have criticized this system for stifling creativity and individuality. A new generation of the avant-garde has broken with this tradition, often receiving its training in the West. In the traditional arts, however, the master-pupil system preserves the secrets and skills of the past. Some master-pupil lineages can be traced to the Kamakura period, from which they continue to use a great master's style or theme. Japanese artists consider technical virtuosity as the sine qua non of their professions, a fact recognized by the rest of the world as one of the hallmarks of Japanese art.

Support for the arts

The Japanese government actively supports the arts through the Agency for Cultural Affairs, set up in 1968 as a special body of the Ministry of Education. The agency's Cultural Properties Protection Division protects Japan’s cultural heritage. The Cultural Affairs Division is responsible for the promotion of art and culture within Japan and internationally, arts copyrights, and improvements in the national language. It supports both national and local arts and cultural festivals, and funds traveling cultural events in music, theater, dance, art exhibitions, and film-making. Special prizes and grants are offered to encourage artists and enable them to train abroad. The agency funds national museums of modern art in Kyoto and Tokyo and the Museum of Western Art in Tokyo. The agency also supports the Japan Academy of Arts, which honors eminent persons of arts and letters. Awards are made in the presence of the Emperor, who personally bestows the highest accolade, the Cultural Medal.

A growing number of large Japanese corporations have collaborated with major newspapers in sponsoring exhibitions and performances and in giving yearly prizes. The most important of the many literary awards are the venerable Naoki Prize and the Akutagawa Prize, equivalent to the Pulitzer Prize in the United States. In 1989, an effort to promote cross-cultural exchange led to the establishment of a Japanese "Nobel Prize" for the arts, the Premium Imperiale, by the Japan Art Association. This prize is funded largely by the mass media conglomerate Fuji-Sankei and winners are selected from a worldwide base of candidates.

A number of foundations promoting the arts arose in the 1980s, including the Cultural Properties Foundation set up to preserve historic sites overseas, especially along the Silk Road in Inner Asia and at Dunhuang in China. Another international arrangement was made in 1988 with the United States' Smithsonian Institution for cooperative exchange of high-technology studies of Asian artifacts. The government plays a major role by funding the Japan Foundation, which provides both institutional and individual grants, effects scholarly exchanges, awards annual prizes, supported publications and exhibitions, and sends traditional Japanese arts groups to perform abroad.

Major cities also provides substantial support for the arts; a growing number of cities in the 1980s had built large centers for the performing arts and, stimulated by government funding, were offering prizes such as the Lafcadio Hearn Prize initiated by the city of Matsue. A number of new municipal museums were also built. In the late 1980s, Tokyo added more than 20 new cultural halls, notably, the large Cultural Village built by Tokyo Corporation and the reconstruction of Shakespeare's Globe Theatre. All these efforts reflect a rising popular enthusiasm for the arts. Japanese art buyers swept the Western art markets in the late 1980s, paying record highs for impressionist paintings and US$51.7 million alone for one blue period Picasso.

See also

- Bonsai

- Japanese architecture

- Japanese literature

- Japanese philosophy

- Japanese tea ceremony

- Kabuki

- Landscape painting

- Noh

- Rakugo

- Shan shui

- Ukiyo-e

Notes

- ↑ Korea, 500–1000 C.E. Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Retrieved December 27, 2019.

- ↑ Asuka and Nara Periods (538–794) Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Retrieved December 27, 2019.

- ↑ Korean Influence on Early Japanese Buddhism. Japanese Buddhist Statuary. Retrieved December 27, 2019.

- ↑ Frederick S. Litten, Animated Film in Japan Until 1919: Western Animation and the Beginnings of Anime (Books on Demand, 2017, ISBN 978-3744830522).

- ↑ Natalie Avella, Graphic Japan: From Woodblock and Zen to Manga and Kawaii (Rotovision, 2004, ISBN 2880467713), 11.

- ↑ Hunter Drohojowska-Philp, "Superflat". artnet.com. Retrieved December 27, 2019.

- ↑ Ronald E. Dolan and Robert L. Worden (eds.), Ceramics Japan: A Country Study (Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, 1994). Retrieved December 27, 2019.

- ↑ Japanese textiles Asia-art.net Retrieved December 27, 2019.

- ↑ An Introduction to Bonsai The Bonsai Site. Retrieved December 27, 2019.

- ↑ Penjing, Chinese Potted Landscapes – Chinese Bonsai Plot55.com Retrieved December 27, 2019.

- ↑ Leonard Koren, Wabi-Sabi for Artists, Designers, Poets and Philosophers (Stone Bridge Press, 1994, ISBN 1880656124).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Alphen, Jan Van et al. Enku 1632-1695. Timeless Images from 17th Century Japan. Antwerpen: Etnografisch Museum., 1999.

- Avella, Natalie. Graphic Japan: From Woodblock and Zen to Manga and Kawaii. Rotovision, 2004. ISBN 2880467713.

- Boardman, John. "The Diffusion of Classical Art in Antiquity." Princeton University Press. 1994. ISBN 0691036802

- Briessen, Fritz van. The Way of the Brush: Painting Techniques of China and Japan. Tuttle, 1999. ISBN 0804831947.

- Conant, Ellen P., Rimer, J. Thomas, Owyoung, Stephen. Nihonga: Transcending the Past: Japanese-Style Painting, 1868-1968. Weatherhill, 1996. ISBN 0834803631.

- Errington, Elizabeth, Joe Cribb, and Maggie Claringbull. 1992. The Crossroads of Asia: transformation in image and symbol in the art of ancient Afghanistan and Pakistan. Cambridge: Ancient India and Iran Trust. ISBN 0951839918.

- Keene, Donald. Dawn to the West. New York: Columbia University Press, 1998. ISBN 0231114354.

- Koren, Leonard. Wabi-Sabi for Artists, Designers, Poets and Philosophers. Stone Bridge Press, 1994. ISBN 1880656124.

- Litten, Frederick S. Animated Film in Japan Until 1919: Western Animation and the Beginnings of Anime. Books on Demand, 2017. ISBN 978-3744830522

- Mason, Penelope. History of Japanese Art. Prentice Hall, 2005. ISBN 0131176021.

- Murakami, Takashi. Little boy: the arts of Japan's exploding subculture. New York: Japan Society, 2005. ISBN 9780300102857.

- Sadao, Tsuneko. Discovering the Arts of Japan: A Historical Overview. Kodansha International, 2003. ISBN 477002939X.

- Schaarschmidt-Richter, Irmtraud. Japanese modern art: painting from 1910 to 1970. Zurich: Edition Stemmle, 2000. ISBN 9783908161868.

- Tapié, Michel. 1957. L'aventure informelle. Nishinomiya, Japan: S. Shimamoto, 1957.

- Tiampo, Ming. 2003. Gutai and Informel Post-war art in Japan and France, 1945—1965. (Dissertation Abstracts International. 65-01.) Thesis (Ph.D.)—Northwestern University, 2003. ISBN 0496660470.

- Tōkyō Kokuritsu Hakubutsukan, Hyōgo Kenritsu Bijutsukan, NHK., & NHK Puromōshon. Alexander the Great: East-West cultural contacts from Greece to Japan = Arekusandorosu Daiō to tōzai bunmei no Kōryū-ten. (Tokyo National Museum) Tokyo: NHK Puromōshon, 2003.

- Weisenfeld, Gennifer S. Mavo: Japanese artists and the avant-garde, 1905-1931. Twentieth-century Japan. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002. ISBN 0520223381.

External links

All links retrieved December 17, 2024.

- The Art of Bonsai Project

- Ruth and Sherman Lee Institute for Japanese Art Collection, online collection of images from the Online Archive of California/University of California Merced

- Japonisme Artists at tricera.net

- Japan - This article contains material from the Library of Congress Country Studies, which are United States government publications in the public domain.

- This article was originally based on material from WebMuseum Paris - Famous Artworks exhibition.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Japanese_art history

- Dōtaku history

- Yayoi_period history

- Haniwa history

- Tōdai-ji history

- Raigō history

- Josetsu history

- Sesshū_Tōyō history

- Kanō_Eitoku history

- Hasegawa_Tōhaku history

- Tawaraya_Sōtatsu history

- Ogata_Kōrin history

- Enkū history

- Nanga_(Japanese_Painting history

- Tanomura_Chikuden history

- National_Diet_Building history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.