Difference between revisions of "Clinical psychology" - New World Encyclopedia

| Line 466: | Line 466: | ||

{{reflist|2}} | {{reflist|2}} | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | |||

===Organizations=== | ===Organizations=== | ||

Revision as of 06:26, 3 February 2007

Clinical psychology is the application of psychology to prevent and relieve psychologically-based distress or dysfunction and to promote subjective well-being. Clinical psychologists assess mental health problems, conduct and use scientific research to understand mental health problems, and develop, provide and evaluate psychological care and interventions (psychotherapy). Although different countries require various educational qualifications to practice clinical psychology, it has traditionally required a Doctorate degree—such as the PhD or PsyD in America[1] or the DClinPsy in Britain—although the U.S. now has accredited Masters-level programs as well. Clinical psychology’s therapeutic practices can address issues with individuals, couples, children, families, small groups, and communities.

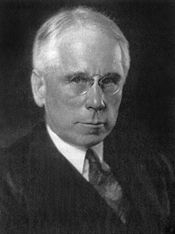

The term was introduced in a 1907 paper by the American psychologist Lightner Witmer, who specifically defined it as the study of individuals, by observation or experimentation, with the intention of promoting change.[1] The American Psychological Association offers a more modern definition of clinical psychology:[2]

- The field of Clinical Psychology integrates science, theory, and practice to understand, predict, and alleviate maladjustment, disability, and discomfort as well as to promote human adaptation, adjustment, and personal development. Clinical Psychology focuses on the intellectual, emotional, biological, psychological, social, and behavioral aspects of human functioning across the life span, in varying cultures, and at all socioeconomic levels.

| Psychology |

| History |

| Psychologists |

| Divisions |

|---|

| Abnormal |

| Applied |

| Biological |

| Clinical |

| Cognitive |

| Comparative |

| Developmental |

| Differential |

| Industrial |

| Parapsychology |

| Personality |

| Positive |

| Religion |

| Social |

| Approaches |

| Behaviorism |

| Depth |

| Experimental |

| Gestalt |

| Humanistic |

| Information processing |

History

Clinical psychology developed partly as a result of a need for additional clinicians to treat mental health problems, and partly as psychological science advanced to the stage where the fruits of psychological research could be successfully applied in clinical settings. The field as it exists today can be said to have begun with Witmer's establishment of the first psychological clinic in 1896 at the University of Pennsylvania. He also founded the first journal of clinical psychology, Psychological Clinic.

Witmer's call for clinical involvement by psychologists was slow to gain acceptance, but by 1914 there were twenty-six more clinics in the United States. While Whitmer focused on individuals with intellectual deficits, others focused on those in mental distress, and clinical psychology was developing in mental hospitals as psychologists gained staff positions, often working alongside psychiatrists.

In the early 20th century, the work of Sigmund Freud and Josef Breuer—whilst not explicitly clinical psychology—gave great impetus to psychological understandings of mental distress and disorder. The assessment-based focus of early clinical psychology came fully into its own during World War I when the U.S. military required clinical psychologists to assess thousands of new soldiers.

It wasn't until 1917 that clinical psychologists began to organize under that name, when the American Association of Clinical Psychology was organized, leading to the Section on Clinical Psychology of the American Psychological Association. This section certified clinical psychologists until 1927, but would not allow clinical psychologists full membership in APA.

Slow growth of the field continued in the 1930s as several scattered, applied psychological organizations in the U.S. formed an alliance under the American Association of Applied Psychology. This group became the primary forum for clinical and applied psychology in the U.S. until APA reorganized in 1945, creating its division of clinical psychology, today known as Division 12.

Before the 1940s, individual psychotherapy was mostly conducted by psychiatrists, leaving clinical psychologists to focus on assessment. This changed during World War II, however, when the military gave greater recognition to the condition they termed "shell shock" which eventually came to be called Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). The need for treatment was such that military called upon clinical psychologists to assist.

After WWII, a similar problem was faced when tens of thousands of soldiers came home needing psychological care. To meet this challenge in the U.S., the Veterans Administration made an enormous investment to set up programs to train doctoral-level clinical psychologists. As a consequence, the U.S. went from having no formal university programs in clinical psychology in 1946 to over half of all PhDs in psychology in 1950 being awarded in clinical psychology.[1] In 1947, a report was drafted that led to the scientist/practitioner model of clinical psychology, known today as the Boulder Model. This called on clinical psychologists to train as scientific psychologists as well as focusing on interpersonal clinical skills. Similar organizational and theoretical developments took place in other countries in the 1950s. The number of clinical psychologists and academic journals proliferated.

Different waves of theory influenced the field after WWII. First Freudian and neo-freudian (or psychodynamic), then humanistic, and finally orientations founded in behaviorism and cognitivism, eventually leading to Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. More recently, orientations founded in transpersonal psychology are becoming more common. Clinical psychology has remained inclusive of an eclectic range of theoretical perspectives and practical methods.

Training

Doctoral level training

Clinical psychologists typically undergo many hours of postgraduate training—usually 4 to 6 years post-Bachelors—under supervision in order to gain demonstrable competence and experience. Today, in America, about half of the licensed psychologists are being trained in the Scientist-Practitioner Model of Clinical Psychology (PhD)—a model that emphasizes research and is usually housed in universities. The other half are being trained within a Practitioner-Scholar Model of Clinical Psychology (PsyD), which has more focus on practice (similar to professional degrees for medicine and law).[3] Both models envision practicing Clinical Psychology in a research-based, scientifically valid manner. The American Psychological Association, among many English-speaking psychological societies, supports both models and encourages accreditation of PhD and PsyD programs that meet its strict academic standards.[4]

Doctorate (PhD and PsyD) programs usually involve some variation on the following 4 to 6 year, 90-unit curriculum:

- Bases of behavior—biological, cognitive-affective, and cultural-social

- Individual differences—personality, lifespan development, psychopathology

- History and systems—development of psychological theories, practices, and scientific knowledge

- Clinical practice—diagnostics, psychological assessment, psychotherapeutic interventions, psychopharmacology, ethical and legal issues

- Clinical experience

- Practicum—usually one or two years of working with clients under supervision in a clinical setting

- Doctoral Internship—usually an intensive one or two year placement in a clinical setting

- Dissertation—PhD programs usually require original quantitative empirical research, while PsyD dissertations often address qualitative research, theoretical scholarship, program evaluation or development, critical literature analysis, or clinical application and analysis

- Specialized electives—many programs offer sets of elective courses for specializations, such as health, child, family, community, or neuropsychology

- Personal psychotherapy—many programs require students to undertake a certain number of hours of personal psychotherapy (with a non-faculty therapist)

Masters level training

There are a number of U.S. schools offering accredited programs in clinical psychology resulting in a Masters degree. These programs require supervised academic training in psychological theory and practice—usually 2 to 3 years post-Bachelors—with a focus on treatment rather than research (similar to the PsyD). Depending on the state, Masters-level graduates are eligible for a license to practice psychotherapy, such as the Licensed Professional Counselor (LPC) or Marriage and Family Therapist (MFT) licenses, usually under the supervision of a licensed psychologist. These programs are usually accredited by the state using guidelines supplied by an organization like the American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy, rather than the APA (which currently only accredits doctoral-level programs).

| Sample Curriculum for MA in Clinical Psychology | ||

| State Required | School Required | Electives |

|

Chemical Dependency: 3 |

Process and Psychotherapy: 4 |

Gay and Lesbian Issues: 2 |

Where subject is required by both the state and the school, it is shown under the school's required column. Similar courses have been lumped together, for example "Group Treatment Techniques" and "Couples Counseling" were combined, their units added together and called "Group and Couples Treatment"—just to keep the table of manageable size.

A typical Masters-level program is 72 units or 84 units with a specialization (such as a focus on child or geriatric psychology).[5] In addition, many programs require students to undertake a minimum number of hours of personal psychotherapy with an approved therapist, which is also a requirement in some states (depending upon the school, the therapy may or may not qualify for academic credit).

Training in Britain

In Britain, clinical psychologists undertake a DClinPsy (or similar) which is a taught doctorate with both clinical and research components. This is a three-year full-time course, taken after a three-year undergraduate degree and some form of experience, usually in either the National Health Service as an Assistant Psychologist or in academia as a Research Assistant. Previously the training required obtaining an MSc and/or MPhil degree, with some also undertaking a PhD and some going on to academic study.[6]

Professional practice

Clinical psychologists can offer a range of professional services, including:[1]

- Provide psychological treatment (psychotherapy)

- Administer and interpret psychological assessment and testing

- Conduct psychological research

- Teach

- Development of prevention programs

- Consultation (especially with schools and businesses)

- Program administration

- Provide expert testimony (forensics)

In practice, clinical psychologists may work with individuals, couples, families, or groups in a variety of settings, including private offices, hospitals, private and public mental health organizations, schools, businesses, and non-profit agencies. Many also are active in academia, teaching, conducting research, or both. Clinical psychologists may choose to specialize in a particular field. Common areas of specialization, some of which can earn board certification,[7] include:

- Specific disorders (trauma, addiction, eating, sleep, sex, depression, anxiety, phobias, etc.)

- Neuropsychological disorders

- Child and adolescent

- Family and relationship counseling

- Health

- Sport

- Forensic

- Organization and business

- School

Clinical Psychology and Psychiatry

Although clinical psychologists and psychiatrists share the same fundamental aim—the alleviation of mental distress—their training, outlook, and methodologies are often quite different. Perhaps the most significant difference is that psychiatrists are medical doctors with 4 years of medical school and another 4 years of residency in a medical setting where they can often choose to specialize, such as working with children or people with specific conditions. As such, they tend to use the medical model to assess psychological problems (i.e. those they treat are seen as patients with an illness) and rely on psychotropic medications as the chief method of addressing them (although many also employ psychotherapy as well). Their medical training does give them an advantage in terms of being able to conduct physical examinations, order and interpret laboratory tests and EEGs, and may order brain imaging studies such as CT or CAT, MRI, and PET scanning.

Clinical psychologists do not usually prescribe medication, although there is a growing movement for psychologists to have limited prescribing privileges. Such privileges require additional, supervised training and education, and would mostly be limited to psychotropic medications. To date, psychologists who obtain additional training in clinical psychopharmacology may prescribe psychotropic medications in Guam, New Mexico, and Louisiana. In general, however, when medication is warranted many psychologists will work in cooperation with psychiatrists so that clients get all their therapeutic needs met.

Unless a psychiatrist voluntarily chooses to get extra training, such as at a psychoanalytic institute, they will have less training in the theory and practice of psychotherapy than will a licensed clinical psychologist. Even though many psychiatrists do seek out such training, the majority of them increasingly focus on medication management, possibly because insurance tends to pay far more for this service than for psychotherapy.[8] Further, psychologists tend to have far more training in psychological assessment.

Licensure

The practice of clinical psychology requires a license in the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and many other countries. Although each of the U.S. states is somewhat different in terms of requirements and licenses, there are three common elements:[9]

- Graduation from an accredited school with the appropriate degree

- Completion of supervised clinical experience

- Passing a written examination and, in some states, an oral examination

| Comparison of Professionals in Clinical Psychology | ||||

| Occupation | Degree | Common Licenses | Prescription Privilege | Ave. 2004 Income |

| Clinical Psychologist | PhD/PsyD | Psychologist | Mostly no | $75,000 |

| Counselor/Psychotherapist (Doctorate) | PhD | MFT/LPC | No | $65,000 |

| School Psychologist | EdD | LEP | No | $78,000 |

| Counselor/Psychotherapist (Masters) | MA/MS/MC | MFT/LPC/LPA | No | $49,000 |

| Psychiatrist | MD/DO | Psychiatrist | Yes | $145,600 |

| Clinical Social Worker | PhD/MSW | LCSW | No | $36,170 |

| Psychiatric Nurse | PhD/MSN | APRN/PMHN | No | $53,450 |

| Expressive/Art Therapist | MA | ATR | No | $45,000 |

Most states also require a certain number of continuing education credits per year in order to renew a license, which can be obtained though various means, such as taking audited classes and attending approved workshops.

Exact requirements vary by license and by state, and are commonly quite complex (see [1] and [2] for examples).

All U.S. state and Canada province licensing boards are members of the Association of State and Provincial Psychology Boards (ASPPB) which created and maintains the Examination for Professional Practice in Psychology (EPPP). Many states require other examinations in addition to the EPPP, such as a jurisprudence (i.e. mental health law) examination and/or an oral examination.[9]

There are several licenses that allow one to practice clinical psychology in various forms, usually awarded in relation to one's educational degree.

- Psychologist. To practice with the title of Psychologist, in almost all cases a Doctorate degree is required (a PhD or PsyD in the U.S.). In addition to finishing 3 to 5 years of coursework, other requirements generally include finishing a dissertation, completing a pre-doc internship, fulfilling a certain number of supervised postdoctoral hours (usually taking 1 to 2 years), and passing the EPPP and any other provincial exams.[15]

- Marriage and Family Therapist (MFT). An MFT license requires a Doctorate or Masters degree (which usually takes 2 to 3 years after a Bachelors and includes an internship and sometimes completion of a thesis). In addition, it usually involves 2 years of post-degree clinical experience under supervision, and licensure requires passing a written exam, commonly the National Examination for Marriage and Family Therapists which is maintained by the American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy. In addition, most state require an oral exam. MFTs, as the title implies, work mostly with families and couples, addressing a wide range of common psychological problems.[16]

- Licensed Professional Counselor (LPC). Similar to the MFT, the LPC license requires a Masters or Doctorate degree, a minimum number of hours of supervised clinical experience in a pre-doc practicum, and the passing of the National Counselor Exam. Similar licenses are the Licensed Mental Health Counselor (LMHC), Licensed Clinical Professional Counselor (LCPC), and Clinical Counselor in Mental Health (CCMH). In some states, after passing the exam, a temporary LPC license is awarded and the clinician may begin the normal 3000-hour supervised internship leading to the full license allowing for the practice as a counselor or psychotherapist, usually under the supervision of a licensed psychologist.[17]

- Licensed Psychological Associate. (LPA) About twenty-six states offer a Masters-only license, a common one being the LPA, which allows for the therapist to either practice independently or (more commonly) under the supervision of a licensed psychologist, depending on the state.[18] Common requirements are 2 to 4 years of post-Masters supervised clinical experience and passing a Psychological Associates Examination. Other titles for this level of licensing include Psychological Technician (Alabama), Psychological Assistant (California), Licensed Clinical Psychotherapist (Kansas), Licensed Psychological Practitioner (Minnesota), Licensed Behavioral Practitioner (Oklahoma), or Psychological Examiner (Tennessee).

Assessment

An important area of expertise for many clinical psychologists is psychological assessment. Such evaluation is usually done in service to gaining insight into and forming hypotheses about psychological or behavioral problems.[19] As such, the results of such assessments are usually used to create generalized impressions rather than diagnoses.

Useful psychological measures must be both valid (i.e., actually measures what it claims to measure) and reliable (i.e., is consistent—internally, over time, and regardless of administrator). Measures that are both highly valid and reliable are usually normed, meaning that they have been given to enough people in a controlled manner so as to produce a statistically meaningful baseline for understanding results compared to a specific group. For example, a score of 100 on the WISC intelligence test is based on the average performance of the norming group, indicating that the testee's overall intelligence probably falls within the average range compared with other children her own age.

There exists literally hundreds of various assessment tools, although only a few have been shown to have high validity and reliability. These measures generally fall within one of several categories, including the following:

- Intelligence & achievement tests. These tests are designed to measure certain specific kinds of cognitive functioning (often refered to as IQ) in comparison to a norming-group. Commonly used today are the Weschler tests (the WAIS-III for adults, the WISC-IV for children, and the WIAT-II achievement test), the Woodcock-Johnson-III, and the Stanford-Binet-5. These tests generally measure areas such as verbal skills (e.g. comprehention and vocabulary), memory (short and long term), attention span, arithmatic, and non-verbal performance (e.g. visual/spacial perception, hand-eye coordination, problem solving, and logical reasoning). These tests have been shown to accurately predict certain kinds of performance, especially scholastic.[19]

- Personality tests. Tests of personality aim to describe characteristic patterns of behavior, thoughts, and feelings that remain relatively stable throughout a person's lifetime. They generally fall within two categories: objective (offering restricted, measured responses, such as yes/no, true/false, or a rating scale) and projective (which allow a person to respond to ambiguous stimuli, presumably revealing non-conscious psychological dynamics). Typical objective tests used today are the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory, the Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory-III, and the California Psychological Inventory. Common projective tests include the Rorschach inkblot test and the Thematic Apperception Test.

- Neuropsychological tests. Neuropsychological tests consist of specifically designed tasks used to measure psychological functions known to be linked to a particular brain structure or pathway. They are typically used to assess impairment after an injury or illness known to affect neurocognitive functioning, or when used in research, to contast neuropsychological abilities across experimental groups. Examples include the Stroop test, the Bender-Gestalt Test, the Trail Making task, and finger tapping.

- Clinical observation. Clinical psychologists are also trained to gather data by observing behavior. The clinical interview is a vital part of assessment, even when using other formalized tools, which can employ either a structured or unstructered format. Such assessment looks at certain areas, such as general appearance and behavior, mood and affect, perception, comprehension, orientation, insight, memory, and content of communication. One common example of a formal interview is the mental status examination, which is often used as a screening tool for treatment or further testing.[19]

Diagnostic impressions

After assessment, clinical psychologists often provide a diagnostic impression. In the U.S., many psychologists use the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (the DSM version IV-TR)—especially when working with an HMO or insurance company—whereas many other countries are more likely to use the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems. Both assume medical concepts and terms, and state that there are categorical disorders that can be diagnosed by set lists of criteria, which serves psychologists by providing a familiar frame of reference for discussing and understanding the clinical experience and for guiding treatment.[20]

The DSM organizes psychological disorders in five axes:

- Axis I: Clinical disorders; Other conditions that may be a focus of clinical attention

- Typical disorders include autism, ADHD, dementia, substance abuse, schizophrenia, depression, bipolar, phobias, PTSD, amnesia, anorexia, insomnia, and adjustment disorder

- Axis II: Personality disorders (generally rigid and self-defeating traits that are persistent over time and affect day to day living)

- Typical disorders include obsessive-compulsive PD, paranoid PD, borderline PD, and narcissistic PD. Mental retardation is also placed on Axis II.

- Axis III: medical conditions contributing to the disorder

- Axis IV: psychosocial and environmental factors contributing to the disorder

- Axis V: Global Assessment of Functioning (on a scale from 100 to 0)

The DSM uses the medical model and views psychological problems in terms of discrete illnesses that can be defined by a minimum set of criteria (such as presenting problems, intensity, behaviors, duration, onset, etc.). While convenient for prescribing medications, there is a growing awareness that this model is not the only way to understand psychological functioning and the various causes of mental distress. As such, there are many debates in the field regarding alternative methods of diagnosing psychological problems.

One such debate is the position of adopting a dimensional model in addition to the current categorical model. Although it is disadvantaged at the moment by a lack of an empirical metric for measuring change or establishing degrees of variation, a dimensional model, according to Jablensky (2005), would have several major advantages, including—addressing quantitative variation and shifts (between various disorders as well as between what is considered normal and pathological); dealing with the presence of multiple conditions; and a more constructive way of looking at otherwise 'sub-threshold' conditions.[20]

Mundt and Backenstrass (2005) describe another variation they call the psychosocial model, which they claim would be far more relevant for the practice of psychotherapy (as opposed to medicine).[21] While the medical model of the DSM is based on assumptions of biology, stability of diagnosis, and objective traits, the psychosocial model is more psychological, intersubjective, and diagnostically flexible over the course of therapy. Like Jablensky, they also suggest that this model be used in conjunction with the medical model, both of which should only be used in the relevant contexts.

British clinical psychologists do not tend to diagnose, but rather use formulation—an individualized map of the difficulties that the patient or client faces, encompassing predisposing, precipitating and perpetuating (maintaining) factors. [citation needed]

Psychotherapy

The central intervention used by clinical psychologists is psychotherapy, which uses a wide range of techniques to change thoughts, feelings, or behaviors in service to enhancing subjective well-being, mental health, and life functioning. There are many theories about the nature and process of psychological change, and it is impossible to articulate them all within one definition. Generally speaking, however, psychotherapy involves a formal relationship between professional and client—usually an individual, couple, family, or small group—that employs a set of procedures to accomplish mutually agreed upon goals. These procedures are intended to form a therapeutic alliance, explore the nature of psychological problems, and encourage new ways of thinking or behaving.

Although there are literally dozens of recognized therapeutic orientations, their differences can often be categorized on two dimensions: insight vs. action and in-session vs. out-session. In the first dimension, some therapies—such as Psychodynamic—place a large emphasis on insight, based on the idea that greater understanding of the motivations underlying one's thoughts and feelings will lead to change. Others—such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy—have more of a focus on making changes in how one acts (which can include the act of mental self-talk), which assumes that insight is not necessary for improvement. On the other dimension, certain orientations—such as Humanistic therapies—emphasize the here-and-now relationship between client and therapist, whereas others—like Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy—recognize the importance of the relationship but place more of a focus on making changes outside of the session (which is reflected in the common technique of giving "homework" assignments). It is common for clinicians to choose one theoretical orientation as their model for understanding the foundations of cognition, behavior, motivation, and the nature of psychological problems, although many develop an eclectic set of therapeutic interventions drawn from multiple orientations.

The methods used are also different in regards to the population being served as well as the context and nature of the problem. Therapy will look very different between, say, a traumatized child, a depressed but high-functioning adult, a group of people recovering from substance dependence, and a ward of the state suffering from terrifying delusions. Other elements that play a critical role in the process of psychotherapy include the environment, culture, age, cognitive functioning, motivation, and duration (i.e. brief or long-term).

The Big Three perspectives

The field generally recognizes three major perspectives regarding the practice of clinical psychology: Psychodynamic, Cognitive Behavioral, and Humanistic (while a growing debate exists about including the Transpersonal perspective, which recognizes a spiritual dimension in psychological well-being).[22]

Psychodynamic

The Psychodynamic perspective developed out of the Psychoanalysis of Sigmund Freud. The core object of Psychoanalysis is to make the unconscious conscious—to make the client aware of his or her own primal drives (namely those relating to sex and aggression) and the various defenses used to keep them in check. The essential tools of the psychoanalytic process are the use of free association and an examination of the client's transference towards the therapist, defined as the tendency to take unconscious thoughts or emotions about a significant person (e.g. a parent) and apply them to another person who is similar in some way.

Many theorists built upon Freud's fundamental ideas, including Anna Freud, Alfred Adler, Carl Jung, Heinz Hartmann, Karen Horney, Erik Erikson, Ronald Fairbairn, Otto Kernberg, Melanie Klein, Heinz Kohut, Margaret Mahler, David Rapaport, Donald Winnicott, and Harry Stack Sullivan. Major variations on Freudian psychoanalysis include Self Psychology, Ego Psychology, and Object Relations Theory. However, there are still common themes that appear within psychodynamic psychology (as the general perspective is now called, although psychoanalysis in its orthodox form is still practiced), including examination of transference and defenses, an appreciation of the power of the unconscious, and a focus on how early developments in childhood have shaped the client's current psychological state.[23]

Cognitive Behavioral

In the 1950s and 1960s, theorists Albert Ellis and Aaron T. Beck independently began combining the perspectives of Cognitive psychology and Behaviorism to create Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT). Essentially, it is based on the idea that how we think (cognition), how we feel (emotion), and how we act (behavior) all interact together. In this hypothesis, certain thoughts or ways of interpreting the world (called schemas) can cause emotional distress or result in behavioral problems. The object of CBT is to discover the biased and irrational thinking that leads to emotional problems and to help the client take control over his or her thinking processes in such a way that will lead to increased well-being.[24] There are various approaches along the lines of CBT, such as Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy and Dialectic Behavior Therapy, both of which have been shown to be effective in treating certain conditions, such as depression and phobias.[25]

These theories are informed by a scientific, empirical perspective; clear operationalization of the "problem" or "issue"; an emphasis on measurement (and measurable changes in cognition and behavior); and measurable goal-attainment.

Humanistic

Humanistic psychology was developed in the 1950s in reaction to both behaviorism and psychoanalysis, largely due to the Person-Centered Therapy of Carl Rogers (often referred to as Rogerian Therapy). Rogers believed that a client needed only three things from a clinician to experience therapeutic improvement—congruence, unconditional positive regard, and empathetic understanding. The aim of much humanistic therapy is to give a holistic description of the person. By using Phenomenology, Intersubjectivity and first-person categories, the humanistic psychologist hopes to get a glimpse of the whole person and not just the fragmented parts of the personality.[26] This aspect of holism links up with another aim of humanistic psychology, which is to seek an integration of the whole person, also called self-actualization. According to humanistic thinking, each individual person already has inbuilt potentials and resources that might help them to build a stronger personality and self-concept. The mission of the humanistic psychologist is to help the individual employ these resources via the therapeutic relationship.

Other major therapeutic orientations

There exists literally dozens of recognized schools or orientations of psychotherapy—the list below represents those that have been pivotal in the development of clinical psychology. Although they all have some typical set of techniques practitioners employ, they are generally better known for providing a framework of theory and philosophy that guides a therapist in his or her working with a client.

Systems or Family Therapy

Systems or Family therapy works with couples and families, and emphasizes family relationships as an important factor in psychological health. The central focus tends to be on interpersonal dynamics, especially in terms of how change in one person will affect the entire system.[27] Therapy is therefore conducted with as many significant members of the "system" as possible. In this way, the psychologist will be able to assess and treat client issues within the broader context in which the clients live. There are several different views within Systems therapy depending on the general therapeutic orientation, all of which have somewhat different methodologies and goals. These can include improving communication, establishing healthy roles, creating alternative narratives, and addressing problematic behaviors.

Gestalt

Gestalt Therapy—co-founded by Fritz Perls, Laura Perls and Paul Goodman in the 1940s–1950s—uses a phenomenological approach to increase awareness of the here-and-now interaction between the self and the environment. There is a strong focus on how and what a client is thinking, feeling, and doing, especially in the immediate therapeutic encounter. Additional influences come from existentialism, particularly the I-thou relationship as it applies to therapy, and the notion of personal choice and responsibility. The objective of Gestalt Therapy, in addition to helping the client overcome symptoms, is to enable him or her to become more fully authentic and creatively alive and to be free from contact blocks and unfinished issues which may diminish optimum satisfaction, fulfillment, and growth. [28]

Gestalt Therapy is well known for techniques called "experiments". These interventions are designed to increase various kinds of self-awareness. While they tend to be spontaneous and created to address immediate issues, there are some standards, the best-known perhaps being the empty chair technique. They are generally intended to explore resistance to authentic contact, which often takes the form of internal conflict. When used well, these experiments can serve to resolve such conflicts and help the client complete unfinished business.[28]

Existential

Existential psychotherapy—which is more of an orientation than any set of techniques—recognizes that to a certain degree, people are largely free to choose who we are and how we interpret and interact with the world. It intends to help the client find deeper meaning in life and to accept responsibility for living. As such, it addresses fundamental issues of life, such as death, aloneness, and freedom. Therapy focuses on the development of a client’s self-awareness by looking deeply into these existential issues. The therapist emphasizes the client’s ability to be self-aware, freely make choices in the present, establish personal identity and social relationships, create meaning, and cope with the natural anxiety of living.[29]

Important writers in existential therapy include Rollo May, Victor Frankl, and Irvin Yalom.

Postmodern

Postmodern psychology says that the experience of reality is a subjective construction built upon language, social context, and history, with no essential truths.[30] Since "mental illness" and "mental health" are not recognized as objective, definable realities, the postmodern psychologist instead sees the goal of therapy as something constructed by the client and therapist.[31] Forms of postmodern psychotherapy include Narrative Therapy, Solution-Focused Therapy, and Coherence Therapy.

Transpersonal

Transpersonal therapy is a relatively new orientation that places a stronger focus on the spiritual facet of human experience.[32] Similar to Existential therapy, it is not a set of techniques so much as a willingness to help a client explore spirituality and/or transcendent states of consciousness. It also is concerned with helping clients achieve his or her highest potential. The orientation is largely informed by Eastern theories on the spiritual and mystical nature of humans, and often focus on enhancing immediate awareness, a fundamental component of meditation.

Important writers in this area include Ken Wilber, Abraham Maslow, Stanislav Grof, John Welwood, and David Brazier.

Integration

In the last couple of decades, there has been a growing movement to integrate the various therapeutic approaches, especially with an increased understanding of cultural, gender, spiritual, and sexual-orientation issues. Clinical psychologists are beginning to look at the various strengths and weaknesses of each orientation while also working with related fields, such as neuroscience, genetics, evolutionary biology, and psychopharmacology. The result is a growing practice of eclecticism, with psychologists learning various systems and the most efficacious methods of therapy with the intent to provide the best solution for any given problem.[33]

Other perspectives

Multiculturalism

Although the theoretical foundations of psychology are rooted in European culture, there is a growing recognition that there exist profound differences between various ethnic and social groups and that systems of psychotherapy need to take those differences into greater consideration.[34] Further, the generations following immigrant migration will have some combination of two or more cultures—with aspects coming from the parents and from the surrounding society—and this process of acculturation can play a strong role in therapy (and might itself be the presenting problem). Culture influences ideas about change, help-seeking, locus of control, authority, and the importance of the individual versus the group, all of which can potentially clash with certain givens in psychotherapeutic theory and practice.[35] As such, more psychologists and training programs are integrating knowledge of various cultural groups in order to inform therapeutic practice in a more culturally sensitive and effective way.

Positive Psychology

Positive psychology is the scientific study of human happiness and well-being, which started to gain momentum in 2000 due to the call of Martin Seligman, then president of the APA. The history of psychology shows that the field has been primarily dedicated to addressing mental illness rather than mental wellness. Applied positive psychology's main focus is on developing positive character strengths and virtues rather than focusing solely on negative problems such as mental disorders.[36]

Feminism

Feminist therapy is an orientation arising from the disparity between the origin of most psychological theories (which have male authors) and the majority of people seeking counseling being female. It focuses on societal, cultural, and political causes and solutions to issues faced in the counseling process. It openly encourages the client to participate in the world in a more social and political way.[37]

Clinical psychology journals

The following represents an (incomplete) listing of significant journals in the field of clinical psychology.

|

|

People who influenced the theory and practice of clinical psychology

|

|

Criticisms and controversies

- Clinical Psychology is sometimes subject to the criticisms leveled at psychiatry, for example by the anti-psychiatry movement. This may be the case, for example, when using categorical medical diagnoses such as in the DSM—which views the client as having an illness—an attitude that some see as demeaning or disempowering.

- Clinical Psychologists are sometimes criticized by psychiatrists for not having the same degree of training or knowledge in general medicine or in medication, or as not being as scientific. There has been controversy over attempts by clinical psychologists to obtain prescribing privileges.

- Although some research has offered evidence that most forms of therapy are equally effective, there remains much debate about the efficacy of various forms of treatment (especially humanistic and Transpersonal therapies). This debate often extends into the comparison between therapy and medication.

- Alternatively, some methods have been criticized as overly-reductionistic, mechanical, and dehumanizing; for example those originating in behaviorism.

See also

|

|

Related lists

- List of psychotherapies

- List of Clinical Psychologists

- List of credentials in psychology

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Compass, B. & Gotlib, I. (2002). Introduction to Clinical Psychology. New York, NY : McGraw Hill. ISBN 0-07-012491-4

- ↑ American Psychological Association, Division 12, "About Clinical Psychology"

- ↑ Norcross, J. & Castle, P. (2002). "Appreciating the PsyD: The Facts." Eye on Psi Chi, 7(1), 22-26.

- ↑ APA. (2005). Guidelines and Principles for Accreditation of Programs in Professional Psychology: Quick Reference Guide to Doctoral Programs.

- ↑ Antioch University. (2006). Master of Arts in Psychology Program Options & Requirements.

- ↑ Cheshire, K. & Pilgrim, D. (2004). A short introduction to clinical psychology. London ; Thousand Oaks, CA : Sage Publications. ISBN 076194768X

- ↑ American Board of Professional Psychology, Specialty Certification in Professional Psychology

- ↑ Downs, Martin. (2005). "Psychology vs. Psychiatry: Which Is Better?" WebMD.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Association of State and Provincial Psychology Boards

- ↑ APA. (2003). Salaries in Psychology 2003: Report of the 2003 APA Salary Survey

- ↑ NIH: Office of Science Education. (2006). Lifeworks: Psychiatrist

- ↑ U.S. Department of Labor: Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2004). Occupational Outlook Handbook: Social Workers

- ↑ U.S. Department of Labor: Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2004). Occupational Outlook Handbook: Registered Nurses

- ↑ NIH: Office of Science Education. (2006). Lifeworks: Art Therapist

- ↑ Kerewsky, Shoshana. (2000). Beyond Internship: Helpful Resources for Obtaining Licensure.

- ↑ American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy, Frequently Asked Questions on Marriage and Family Therapists

- ↑ National Board for Certified Counselors

- ↑ Northamerican Association of Masters in Psychology. (2004). Licensure Information Retrieved Jan. 7, 2007.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Groth-Marnat, G. (2003). Handbook of Psychological Assessment, 4th ed. Hoboken, NJ : John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0471419796

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Jablensky, Assen. (2005). Categories, dimensions and prototypes: Critical issues for psychiatric classification. Psychopathology, 38(4), 201

- ↑ Mundt, Christoph & Backenstrass, Matthias. (2005). Psychotherapy and classification: Psychological, psychodynamic, and cognitive aspects. Psychopathology, 38(4), 219

- ↑ Keutzer, Carolin. (1984). Transpersonal psychotherapy: Reflections on the genre. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 15(6), 868

- ↑ Gabbard, Glen. (2005). Psychodynamic Psychiatry in Clinical Practice, 4th Ed. Washington, DC : American Psychiatric Press. ISBN 1-58562-185-4

- ↑ Beck, A., Davis, D., and Freeman, A. (2007). Cognitive Therapy of Personality Disorders, 2nd Ed. New York : Guilford Press. ISBN 978-1-59385-476-8

- ↑ Lynch, Thomas and Robins, Clive. (1997). Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder Using Dialectical Behavior Therapy. The Journal, 8(1).

- ↑ Rowan, John. (2001). Ordinary Ecstasy : The Dialectics of Humanistic Psychology. London, UK : Brunner-Routledge. ISBN 0415236339

- ↑ Bitter, J. & Corey, G. (2001). "Family Systems Therapy" in Gerald Corey (ed.), Theory and Practice of Counseling and Psychotherapy. Belmost, CA : Brooks/Cole.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Woldt, Ansel and Toman, Sarah. (2005). Gestalt Therapy: History, Theory, and Practice. Thousand Oaks, CA. : Sage Publications. ISBN 0761927913

- ↑ Van Deurzen, Emmy. (2002). Existential Counselling & Psychotherapy in Practice. London; Thousand Oaks : Sage Publications. ISBN 0761962239

- ↑ Slife, B., Barlow, S. and Williams, R. (2001). Critical issues in psychotherapy : translating new ideas into practice. London : SAGE. ISBN 0761920803

- ↑ Blatner, Adam. (1997). The Implications of Postmodernism for Psychotherapy. Individual Psychology, 53(4), 476-482.

- ↑ Boorstein, Seymour. (1996). Transpersonal Psychotherapy. Albany : State University of New York Press. ISBN 0791428354

- ↑ Norcross, John and Goldfried, Marvin. (2005). The Future of Psychotherapy Integration: A Roundtable. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 15(4), 392

- ↑ La Roche, Martin. (2005). The cultural context and the psychotherapeutic process: Toward a culturally sensitive psychotherapy. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 15(2), 169–185

- ↑ Young, Mark. (2005). Learning the Art of Helping, 3rd ed. Ch. 4, "Helping Someone Who is Different." Upper Saddle River, NJ : Pearson Education. ISBN 013111753X

- ↑ Snyder, C. and Lopez, S. (2001). Handbook of Positive Psychology. New York ; Oxford : Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195135334

- ↑ Hill, Marcia and Ballou, Mary. (2005). The foundation and future of feminist therapy. New York : Haworth Press. ISBN 0789002019

Organizations

- APA Society of Clinical Psychology (Division 12)

- American Academy of Clinical Psychology

- American Board of Professional Psychology

- American Counseling Association

- American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy

- Association of State and Provincial Psychology Boards (ASPPB)

- Society for the Exploration of Psychotherapy Integration

- National Institute of Mental Health

Information

- Info on the field of psychology form the U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics

- The Psychology Wiki

- Classics in the History of Psychology

- All About Psychotherapy

Career & Education

- Careers in Psychology

- Careers in Clinical and Counseling Psychology

- Graduate School Programs in Clinical Psychology

- Getting into Graduate School, APA

International

- International Society of Clinical Psychology

- International PSY Congresses

- Canadian Psychological Society

- British Psychological Society

- Psychology Societies Outside the U.S.

Finding a therapist

- Find A Psychologist, APA

- Find A Therapist, Psychology Today

- TherapistLocator.net, American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.