The story of Cain and Abel, written in the Torah and the Bible at Genesis 4, and Qur'an at 5:27-32, tells of the first human murder when Cain killed his brother Abel. They were the sons of Adam and Eve and the murder a result of their Fall. Many religious faiths view this as the prototypical murder and paradigm for conflict and violence. While some view this story as merely a story of the origin of humanity, and others as a justification of murder, it is generally interpreted as a tragedy in human relationships. Cain and Abel often represent different personality types or social positions. Cain represents the firstborn, sinful, worldly, privileged, a farmer, a city-builder and bad son. Abel represents the junior, faithful, spiritual, herdsman, and good son.

The Cain and Abel story is set in the Ancient Near East about 6,000 years ago. Many modern scholars believe the biblical account derived from earlier stories of conflict between the traditional nomadic way of life of the Israelites and the agricultural way of life which was developing in the Fertile Crescent.

Christian theology derived from St. Augustine sees a constant separation of Cain and Abel, the former destined for hell and the latter bound for heaven. Social psychologists would view Cain's action as an example of the frustration-aggression hypothesis and advocate teaching non-violent responses to frustration. In basic disagreement with the Augustinian view, many today argue that God equally loves both sons and desires the reconciliation of Cain and Abel as the brothers they are. Successful strategies for the resolution of Cain-Abel conflicts can be seen as a paradigms for conflict resolution generally.

The Scriptures

Genesis 4 presents a brief account of the brothers. It states that Cain was a tiller of the land while his younger brother Abel was a shepherd, and that one day they both offered sacrifice to God. Cain offered fruit and grain, and Abel offered fresh meat from his flock. For an unspecified reason, God favored Abel's sacrifice, and reject's Cain's. Cain became very angry. God does not judge Cain but asks him why he is angry giving him the opportunity to reflect and change his attitude. God then tells Cain that it is up to him what happens. If he changes, he will be able to control his anger and not sin. If one the other hand he does not, his anger will overcome him and he will commit a terrible crime. Subsequently Cain murders Abel for an unspecified reason, often assumed simply to be jealousy over God's favoritism. The account continues with God apparently unable to find either Abel or his body, and then questioning Cain about Abel's location. Again God gives Cain an opportunity to take responsibility for what he has done and repent. However in a response that has become a well-known saying, Cain denies that he has done anything wrong or even that he knows anything about it saying, "Am I my brother's keeper?"

Finally, seeing through Cain's deception, as "the voice of [Abel's] blood is screaming to [God] from the ground," God curses Cain to a life of wandering the earth. Cain is overwhelmed by this and appeals in fear of being killed by other men, and so God places a "mark" on Cain so that he would not be killed, stating that "whomsoever kills Cain, vengeance shall be upon him sevenfold." Cain then departs, "to the land wandering." Early translations instead stated that he departed "to the Land of Nod," which is generally considered a mistranslation of the Hebrew word Nod, meaning "wandering." Despite his curse, Cain is later mentioned as fathering a lineage of children, and founding a city, which he named Enoch after the name of his son.

Names

Cain and Abel are English renderings of the Hebrew names קַיִן / קָיִן and הֶבֶל / הָבֶל, respectively, from the Bible. In the modern Hebrew transliteration, these are rendered Qáyin and Hével. In the Qur'an, Abel is named as Hābīl (هابيل), but Cain is not named, though Islamic tradition records his name as Qābīl (قابيل).

The word Hevel (Abel) appears in Ecclesiastes in a context implying it should be translated "pointless" (the King James Version translates it as "vanity"), and also appears in the masoretic text at 1 Samuel 6:18, apparently with the meaning "lamentation." Both biblical uses are traditionally taken to imply that Abel's name is word play, in reference to Abel's brief life.

The Bible gives a folk etymology for Cain's name; "And Adam knew Eve his wife, and she conceived and bare Cain, and said I have gotten a man from the Lord." The word here translated "gotten" being qanithi in the original Hebrew, a word derived from qanah ("to get"), and hence a word-play on qayin, though there is no etymological relationship between these two words.

Academic considerations have produced a more direct pun. Abel is here thought to derive from a word meaning "herdsman", with the modern Arabic cognate ibil, which now more specifically means "camels." Cain (qayin / qyn), on the other hand, is thought to be cognate to the mid-first millennium B.C.E. South Arabian word qyn, meaning "metal smith."[1] Hence their names are merely descriptions of the roles they take in the story—Abel as a pastoral farmer, and Cain as an agriculturist.

A once common, but false, English etymology held that Abel was composed from ab and el, effectively meaning source of God. However, this is a fallacy, as the original Hebrew only contains the three letters HVL (הָבֶל), which is quite different from ABEL (אבאל).

Theological Explanations

To explain God's preference for Abel's offering, Judaism has traditionally pointed to the blood sacrifices (korbanot) as ordained in Leviticus, Deuteronomy, and elsewhere. The New Testament, on the other hand, says that Abel made his offering one of faith (Hebrews 11:4), whereas Cain was inherently evil (1 John 3:12). Classical Christian theology notes that Abel's sacrifice was acceptable to God because it was a blood sacrifice. Christians further extend this to the shedding of Abel's own blood, both observations made so as to argue how they prefigure Jesus Christ, and his "shedding blood" for our "salvation." St. Augustine developed the classical Christian view in The City of God. He used Cain and Abel as a metaphor for two types of people and the cities they build. According to Augustine, the Cain-type earthly city and the Abel-type heavenly city were respectively founded based on "love of self" to the point of a contempt of God, on one hand, and "love of God" to the point of self-contempt, on the other. Mormonism adds that Cain loved Satan more than God, and made the sacrifice because Satan told him to.

Although most groups have interpreted Cain's motive in killing Abel as simply being one of jealousy concerning God's favoritism of Abel, this is not always the only view. The Midrash, as well as the Qur'an, records that the real motive involved rivalry over a woman. According to Midrashic tradition, Cain and Abel each had twin sisters, whom they were to marry. The Midrash and Qur'an record that Abel's promised wife was the more beautiful, and hence Cain desired to rid himself of Abel, whose presence was inconvenient. In the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and the Community of Christ, there is a different view, found in the Book of Moses (part of the Joseph Smith Translation of the Bible), which describes Cain's motive as jealousy of Abel's livestock.

Vengeance, pacifism, dualistic separation, or reconciliation?

In the Torah, God is frustrated by the violent and unfaithful society descended from Cain, and the story of the flood judgment describes God's attempt to start the human race afresh with Noah's family. Noah was a faithful descendant of Seth, a younger brother of Cain and Abel. God vowed never to use that approach to eliminate evil from the world again (Gen. 8:20-22).

In classical times, as well as more recently, Abel was regarded as the first innocent victim of the power of evil, and hence the first martyr. In the esoteric Book of Enoch (22:7), the soul of Abel is described as having been appointed as the chief of martyrs in Sheol, crying for vengeance through the destruction of the seed of Cain. This theme is later repeated in the Testament of Abraham, where Abel has been raised to the position of judge of the souls:

…an awful man sitting upon the throne to judge all creatures, and examining the righteous and the sinners. He being the first to die as martyr, God brought him hither [to the place of judgment in the nether world] to give judgment, while Enoch, the heavenly scribe, stands at his side writing down the sin and the righteousness of each. For God said: I shall not judge you, but each man shall be judged by man. Being descendants of the first man, they shall be judged by his son until the great and glorious appearance of the Lord, when they will be judged by the twelve tribes of Israel, and then the last judgment by the Lord Himself shall be perfect and unchangeable. (A:13/B:11)

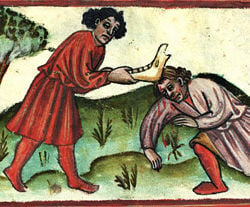

While the Torah simply states that Cain killed Abel, the Midrash records the tradition that the two brothers fought, until Abel, who was the stronger of the two, overcame Cain, but mercifully spared his life. Cain, however, took Abel unawares and, overpowering him, killed him. The exact method of murder varies with some traditions proposing a stone, others a cane, and others by strangulation. Medieval traditions viewed the murder weapon as being a plow. The Qur'anic version is similar, stating that Abel refused to defend himself against Cain, and hence, in the view of some liberal movements within Islam, Abel is the primary Qur'anic proponent of pacifism and non-violence.

In Christianity, comparisons are sometimes made between the death of Abel and that of Jesus. In the Gospel of Matthew (at 23:35), Jesus speaks of Abel as “righteous.” The Epistle to the Hebrews, however, states that “The blood of sprinkling ... [speaks] better things than that of Abel” (Hebrews 12:24), i.e., the blood of Jesus is interpreted as demanding mercy (as per Christian belief about Jesus' death) but that of Abel as demanding vengeance (hence the curse and mark).

In The City of God, St. Augustine wrote of two types of men forming two types of cities: the way of Babylon (Cain) and the way of Jerusalem (Abel). The earthly cities of Cain-type were corrupt and hopeless and destined for hell, whereas as God's chosen people, those represented by the Church, which inherited the mantle from Jerusalem, Abel-type believers were pilgrims on this earth moving toward a higher and more perfect eternal life in heaven. This frequently led to the view that God's chosen people were more important than others, and hence a basis for religious bigotry. This often meant that the Abel-type people could use the earth and run roughshod over Cain-type people and their social institutions to promote their pilgrimage to heaven. This promoted a dualistic worldview in which of the spheres of Church and State in Western civilization would never be reconciled. Some scholars attribute the dualistic outlook of Augustine to his prior affiliation with Manichaeism with its cosmic dualism of good and evil.

But, many people from different quarters critique Augustine's argument, saying that one brother cannot be in heaven without the other. Loving parents can never rest in peace when their children are not at peace. It develops a paradigm of peaceful reconciliation of the two brothers, whose unity provides a foundation for the entire family to be restored. Thus one of the goals of God's providence is for Abel-type and Cain-type people to overcome their fallen nature and live together harmoniously, perfecting the balance of internal and external in each person's character and in the character of society.

This position on the need for reconciliation has been particularly echoed by Rabbi Arthur Waskow[2] of the Jewish Renewal movement and Jeff Dietrich[3] of the Los Angeles Catholic Worker. Waskow acknowledges God's parental care for Cain, by saying that God actually called and invited Cain to "what is a redemptive choice" of becoming a genuine adult in front of God by not murdering Abel. Although Cain ended up murdering Abel, continues Waskow, later sagas such as that of the embrace between Esau and Jacob and that of the reconciliation between Joseph and his eleven brothers clearly tell the main thesis of the Book of Genesis, which is brotherly reconciliation, as the path to "reopen" the way to the Garden of Eden.

In modern times this Cain-Abel division is seen in religion, politics, and the economy, all of which are maturing to create a better social environment. In religion, Western Christianity, with its emphasis on a personal relationship with God and personal responsibility, is in an Abel position; in politics, democracy, with its emphasis on freedom, provides an environment where people have an opportunity to achieve fulfillment; and in economics, free-market forces are an engine for the production of goods and services that can improve life for all. However, these Abel-type social institutions are not perfected, but must be further developed through unity with their Cain-type counterparts that emphasize reason, convergent values, and mutual prosperity. According to Jeff Dietrich, the key to this growth of society through mutual reconciliation of Abel and Cain is Abel's awareness of his own imperfection — symbolized by Jacob's experience of "woundedness" on the Jabbok where his thigh was wounded by the angel with whom he wrestled throughout the night. This kind of awareness of his own imperfection or woundedness on the part of Abel can help him develop a feeling of compassion for and reconciliation with Cain.[3]

The mark of Cain

Much has been written about the curse and "mark" of Cain, and Cain being condemned to a life of wandering. Although most scholars believe the writer of this part of the story had a clear reference in mind that readers would understand, there is little consensus as to exactly what the mark meant. The word translated as "mark" could mean a sign, omen, warning, or remembrance. In the Torah, the same word is used to describe the stars as signs or omens, circumcision as a token of God's covenant with Abraham, and the signs performed by Moses before Pharaoh.

Early Syriac Christianity interpreted the mark as a permanent change in skin color, namely that Cain was turned black. This re-emerged amongst Protestant groups, and the curse was often used by them in some attempts to justify racism of one form or another, such as the slave trade, banning interracial marriage, and apartheid. These views have since been disowned by most Protestant groups, many now pointing to the tale of Snow-white Miriam as a counter argument.

It is significant to note that these interpretations were not, and are not, recognized by Orthodox Christianity, Roman Catholicism, or Coptic Christianity. Baptist and Catholic groups both consider the idea of God cursing an individual to be out of character, and hence take a different stance. Catholics officially view the curse being brought by the ground itself refusing to yield to Cain, whereas some Baptists view the curse as Cain's own aggression, something already present that God merely pointed out rather than added.

Burial

Although not explicit, God's apparent inability to identify the corpse of Abel has led many to speculate that Abel was buried, or at least hidden. Since at this point in the Genesis account, no one had ever died, the concept of burial was unknown. In the Talmud, the corpse remained unburied for some time, with Abel's dog keeping away predators and scavengers, until at God's command, two turtledoves flew down in front of Adam and Eve, one dying when it landed. The other dug a hollow place and moved the dead one into it, hence Adam and Eve did likewise to Abel's body. The Midrash records the opinion that the place of murder was cursed to be desolate forever, with later Jewish tradition identifying it as Damascus.

According to the Coptic Book of Adam and Eve (at 2:1-15), and the Syriac Cave of Treasures, Abel's body, after many days of mourning, was placed in the Cave of Treasures, before which Adam and Eve, and descendants, offered their prayers. In addition, the Sethite line of the Generations of Adam swear by Abel's blood to segregate themselves from the unrighteous.

In the Qur'an, it was Cain who buried Abel, and he was prompted to do so by a single raven scratching the ground, on God's command. The Qur'an states that upon seeing the raven, Cain regretted his action. Instead of cursing Cain, God chose to create a law against murder since he had not done so before:

- If anyone slew a person—unless it be for murder or for spreading mischief in the land—it would be as if he slew the whole people; and if anyone saved a life, it would be as if he saved the life of the whole people.

Critical Scholarship and Sumerian Parallels

In critical scholarship, the prevailing theory is that the story is composed of a number of layers, with the original layer deriving from the Sumerian tale of the wooing of Inanna. In the tale, seen as representing the ancient conflict between nomadic herders and settled agrarian farmers, Dumuzi, the god of shepherds, and Enkimdu, the god of farmers, are competing for the attention of Inanna, chief goddess. Dumuzi is brash and aggressive, but Enkimdu is placid and easy going, so Inanna favors Enkimdu. However, on hearing this, Dumuzi starts boasting about how great he is, and exhibits such strong charisma that Enkimdu tells Inanna to marry Dumuzi and then wanders away.

The biblical correspondence in this theory being God to Inanna, Abel, the shepherd, to Dumuzi, and Cain, the farmer, to Enkimdu, and equating only to the competitive part of the story, Cain wandering away, and the extra-biblical traditions concerning the involvement of a beautiful woman. The presence of sacrifices, rather than mere words, in the biblical story, is sometimes seen as simply the priesthood's spin on the story, to emphasize that one form of sacrifice is better than the other.

In later mythology, though still prior to 1500 B.C.E.., Dumuzi had become conflated with Enkimdu, and so acted as a general agricultural deity, though still retaining some of the earlier myths. In his more general role, since he was responsible for the yearly crop-cycle, Dumuzi became seen as a life-death-rebirth deity. Exactly how the myth fits in with the marriage of Dumuzi to Inanna is not clear, since the surviving copies abruptly begin with Inanna descending to the underworld for an unknown reason. Innana can only escape by exchanging herself for a god not in the underworld, and so considers each of them in turn. Dumuzi is only too glad she has gone, and so, in anger, she sends demons upon him, and he dies, thus releasing her. She then changes her mind, showing favor, and bringing Dumuzi back by persuading his sister to take his place for six months each year (hence starting the annual cycle).

This murder of Dumuzi is thought, critically, to be the source of the murder of Abel. Since God, unlike Inanna, was seen as being powerful enough not to get stuck in the underworld, he would have had no need to escape, and so no motive to kill Abel, hence the blame shifting to the jealous Cain/Enkimdu. The part of the story involving perpetual annual resurrection and death is not given to Abel, who is supposedly merely mortal.

There are parallels to Cain being viewed as a city-builder and agriculturalist, and the condemnation of the city-builders of Babylon which derived its power from agricultural life in Genesis 11 or the worldly ways of Sodom and Gomorrah, and God's displeasure with such ways of life (Gen. 19). The biblical writers in Babylonian captivity may have sought theological justification for the pastoral life of their ancestors while cursing the worldly ways of their Babylonian captors.

Notes

- ↑ Richard S. Hess, Studies in the Personal Names of Genesis 1-11 (Neukirchener Verlag, 1993), 24-25.

- ↑ Rabbi Arthur Waskow, "Brothers Reconciled," Retrieved November 6, 2007.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Jeff Dietrich, "Wrestling and Reconciling," Retrieved November 6, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Algeo, John. "Cain and Abel: A Theosophical Midrash." Quest January-February 1997. Retrieved May 16, 2013.

- Aronson, Elliot. "Human Aggression" in The Social Animal. San Francisco, CA: W. H. Freeman, 1965. ISBN 071671230X

- Augustine of Hippo. The City of God. New York, NY: Image Books, 1958. ISBN 0385029101

- The Book of Jubilees iv. 1-12. R. H. Charles, tr. Retrieved May 16, 2013.

- "Cain and Abel in the Qur'an" Answering Islam. Retrieved May 16, 2013.

- Divine Principle. New York, NY: Holy Spirit Association for the Unification of World Christianity, 1977. ISBN 978-0910621038

- The Jewish Encyclopaedia 1st ed., vol. 1. New York, NY: KTAV Publishing House, 1901.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.