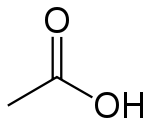

Acetic acid

| Acetic acid | |

|---|---|

| |

| General | |

| Systematic name | Acetic acid Ethanoic acid |

| Other names | Methanecarboxylic acid Acetyl hydroxide (AcOH) Hydrogen acetate (HAc) |

| Molecular formula | CH3COOH |

| SMILES | CC(=O)O |

| Molar mass | 60.05 g/mol |

| Appearance | Colorless liquid or crystals |

| CAS number | [64-19-7] |

| Properties | |

| Density and phase | 1.049 g cm−3, liquid 1.266 g cm−3, solid |

| Solubility in water | Fully miscible |

| In ethanol, acetone In toluene, hexane In carbon disulfide |

Fully miscible Fully miscible Practically insoluble |

| Melting point | 16.5 °C (289.6 ± 0.5 K) (61.6 °F)[1] |

| Boiling point | 118.1 °C (391.2 ± 0.6 K) (244.5 °F)[1] |

| Acidity (pKa) | 4.76 at 25°C |

| Viscosity | 1.22 mPa·s at 25°C |

| Dipole moment | 1.74 D (gas) |

| Hazards | |

| MSDS | External MSDS |

| EU classification | Corrosive (C) |

| NFPA 704 | |

| Flash point | 43°C |

| R-phrases | R10, R35 |

| S-phrases | S1/2, S23, S26, S45 |

| U.S. Permissible exposure limit (PEL) |

10 ppm |

| Supplementary data page | |

| Structure & properties |

n, εr, etc. |

| Thermodynamic data |

Phase behaviour Solid, liquid, gas |

| Spectral data | UV, IR, NMR, MS |

| Related compounds | |

| Related carboxylic acids |

Formic acid Propionic acid Butyric acid |

| Related compounds | Acetamide Ethyl acetate Acetyl chloride Acetic anhydride Acetonitrile Acetaldehyde Ethanol thioacetic acid |

| Except where noted otherwise, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25°C, 100 kPa) | |

Acetic acid, also known as ethanoic acid, is an organic chemical compound best recognized for giving vinegar its sour taste and pungent smell. It is one of the simplest carboxylic acids (the second-simplest, after formic acid) and has the chemical formula CH3COOH. In its pure, water-free state, called glacial acetic acid, it is a colorless, hygroscopic liquid that freezes below 16.7°C (62°F) to a colorless crystalline solid. It is corrosive, and its vapor irritates the eyes, produces a burning sensation in the nose, and can lead to a sore throat and lung congestion. The term acetate is used when referring to the carboxylate anion (CH3COO-) or any of the salts or esters of acetic acid.

This acid is an important chemical reagent and industrial chemical useful for the production of various synthetic fibers and other polymeric materials. These polymers include polyethylene terephthalate, used mainly in soft drink bottles; cellulose acetate, used mainly for photographic film; and polyvinyl acetate, for wood glue. In households, diluted acetic acid is often used in descaling agents. The food industry uses it (under the food additive code E260) as an acidity regulator.

The global demand for acetic acid has been estimated at around 6.5 million metric tons per year (Mt/a). Of that amount, approximately 1.5 Mt/a is met by recycling; the remainder is manufactured from petrochemical feedstocks or biological sources.

Nomenclature

The trivial name acetic acid is the most commonly used and officially preferred name by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC). This name derives from acetum, the Latin word for vinegar. The synonym ethanoic acid is a systematic name that is sometimes used in introductions to chemical nomenclature.

Glacial acetic acid is a trivial name for water-free acetic acid. Similar to the German name Eisessig (literally, ice-vinegar), the name comes from the ice-like crystals that form slightly below room temperature at 16.7°C (about 62°F).

The most common and official abbreviation for acetic acid is AcOH or HOAc where Ac stands for the acetyl group CH3−C(=O)−;. In the context of acid-base reactions the abbreviation HAc is often used where Ac instead stands for the acetate anion (CH3COO−), although this use is regarded by many as misleading. In either case, the Ac is not to be confused with the abbreviation for the chemical element actinium.

Acetic acid has the empirical formula CH2O and the molecular formula C2H4O2. The latter is often written as CH3-COOH, CH3COOH, or CH3CO2H to better reflect its structure. The ion resulting from loss of H+ from acetic acid is the acetate anion. The name acetate can also refer to a salt containing this anion or an ester of acetic acid.

History

Vinegar is as old as civilization itself, perhaps older. Acetic acid-producing bacteria are present throughout the world, and any culture practicing the brewing of beer or wine inevitably discovered vinegar as the natural result of these alcoholic beverages being exposed to air.

The use of acetic acid in chemistry extends into antiquity. In the third century B.C.E., Greek philosopher Theophrastos described how vinegar acted on metals to produce pigments useful in art, including white lead (lead carbonate) and verdigris, a green mixture of copper salts including copper(II) acetate. Ancient Romans boiled soured wine in lead pots to produce a highly sweet syrup called sapa. Sapa was rich in lead acetate, a sweet substance also called sugar of lead or sugar of Saturn, which contributed to lead poisoning among the Roman aristocracy. The eighth-century Persian alchemist Jabir Ibn Hayyan (Geber) concentrated acetic acid from vinegar through distillation.

In the Renaissance, glacial acetic acid was prepared through the dry distillation of metal acetates. The sixteenth-century German alchemist Andreas Libavius described such a procedure, and he compared the glacial acetic acid produced by this means to vinegar. The presence of water in vinegar has such a profound effect on acetic acid's properties that for centuries many chemists believed that glacial acetic acid and the acid found in vinegar were two different substances. The French chemist Pierre Adet proved them to be identical.

In 1847, the German chemist Hermann Kolbe synthesized acetic acid from inorganic materials for the first time. This reaction sequence consisted of chlorination of carbon disulfide to carbon tetrachloride, followed by pyrolysis to tetrachloroethylene and aqueous chlorination to trichloroacetic acid, and concluded with electrolytic reduction to acetic acid.

By 1910, most glacial acetic acid was obtained from the "pyroligneous liquor" from distillation of wood. The acetic acid was isolated from this by treatment with milk of lime, and the resultant calcium acetate was then acidified with sulfuric acid to recover acetic acid. At this time Germany was producing 10,000 tons of glacial acetic acid, around 30 percent of which was used for the manufacture of indigo dye.[2][3]

Chemical properties

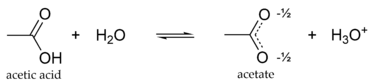

- Acidity

The hydrogen (H) atom in the carboxyl group (−COOH) in carboxylic acids such as acetic acid can be given off as an H+ ion (proton), giving them their acidic character. Acetic acid is a weak, effectively monoprotic acid in aqueous solution, with a pKa value of 4.8. Its conjugate base is acetate (CH3COO−). A 1.0 M solution (about the concentration of domestic vinegar) has a pH of 2.4, indicating that merely 0.4 percent of the acetic acid molecules are dissociated.

- Cyclic dimer

The crystal structure of acetic acid[4] shows that the molecules pair up into dimers connected by hydrogen bonds. The dimers can also be detected in the vapour at 120 °C. They also occur in the liquid phase in dilute solutions in non-hydrogen-bonding solvents, and to some extent in pure acetic acid,[5] but are disrupted by hydrogen-bonding solvents. The dissociation enthalpy of the dimer is estimated at 65.0–66.0 kJ/mol, and the dissociation entropy at 154–157 J mol–1 K–1.[6] This dimerization behavior is shared by other lower carboxylic acids.

- Solvent

Liquid acetic acid is a hydrophilic (polar) protic solvent, similar to ethanol and water. With a moderate dielectric constant of 6.2, it can dissolve not only polar compounds such as inorganic salts and sugars, but also non-polar compounds such as oils and elements such as sulfur and iodine. It readily mixes with many other polar and non-polar solvents such as water, chloroform, and hexane. This dissolving property and miscibility of acetic acid makes it a widely used industrial chemical.

- Chemical reactions

Acetic acid is corrosive to many metals including iron, magnesium, and zinc, forming hydrogen gas and metal salts called acetates. Aluminum, when exposed to oxygen, forms a thin layer of aluminum oxide on its surface which is relatively resistant, so that aluminium tanks can be used to transport acetic acid. Metal acetates can also be prepared from acetic acid and an appropriate base, as in the popular "baking soda + vinegar" reaction. With the notable exception of chromium(II) acetate, almost all acetates are soluble in water.

Acetic acid undergoes the typical chemical reactions of a carboxylic acid, such producing ethanoic acid when reacting with alkalis, producing a metal ethanoate when reacted with a metal, and producing an metal ethanoate, water and carbon dioxide when reacting with carbonates and hydrogen carbonates. Most notable of all its reactions is the formation of ethanol by reduction, and formation of derivatives such as acetyl chloride by what is called "nucleophilic acyl substitution." Other substitution derivatives include acetic anhydride; this anhydride is produced by loss of water from two molecules of acetic acid. Esters of acetic acid can likewise be formed via Fischer esterification, and amides can also be formed. When heated above 440 °C, acetic acid decomposes to produce carbon dioxide and methane, or ketene and water.

- Detection

Acetic acid can be detected by its characteristic smell. A color reaction for salts of acetic acid is iron(III) chloride solution, which results in a deeply red color that disappears after acidification. Acetates when heated with arsenic trioxide form cacodyl oxide, which can be detected by its malodorous vapors.

Biochemistry

The acetyl group, derived from acetic acid, is fundamental to the biochemistry of virtually all forms of life. When bound to coenzyme A it is central to the metabolism of carbohydrates and fats. However, the concentration of free acetic acid in cells is kept at a low level to avoid disrupting the control of the pH of the cell contents. Unlike some longer-chain carboxylic acids (the fatty acids), acetic acid does not occur in natural triglycerides. However, the artificial triglyceride triacetin (glycerin triacetate) is a common food additive, and is found in cosmetics and topical medicines.

Acetic acid is produced and excreted by certain bacteria, notably the Acetobacter genus and Clostridium acetobutylicum. These bacteria are found universally in foodstuffs, water, and soil, and acetic acid is produced naturally as fruits and some other foods spoil. Acetic acid is also a component of the vaginal lubrication of humans and other primates, where it appears to serve as a mild antibacterial agent.[7]

Production

Acetic acid is produced both synthetically and by bacterial fermentation. Today, the biological route accounts for only about 10 percent of world production, but it remains important for vinegar production, as many of the world food purity laws stipulate that vinegar used in foods must be of biological origin. About 75 percent of acetic acid made for use in the chemical industry is made by methanol carbonylation, explained below. Alternative methods account for the rest.[8]

Total worldwide production of virgin acetic acid is estimated at 5 Mt/a (million metric tons per year), approximately half of which is produced in the United States. European production stands at approximately 1 Mt/a and is declining, and 0.7 Mt/a is produced in Japan. Another 1.5 Mt are recycled each year, bringing the total world market to 6.5 Mt/a.[9] The two biggest producers of virgin acetic acid are Celanese and BP Chemicals. Other major producers include Millennium Chemicals, Sterling Chemicals, Samsung, Eastman, and Svensk Etanolkemi.

Methanol carbonylation

Most virgin acetic acid is produced by methanol carbonylation. In this process, methanol and carbon monoxide react to produce acetic acid according to the chemical equation:

The process involves iodomethane as an intermediate, and occurs in three steps. A catalyst, usually a metal complex, is needed for the carbonylation (step 2).

- (1) CH3OH + HI → CH3I + H2O

- (2) CH3I + CO → CH3COI

- (3) CH3COI + H2O → CH3COOH + HI

By altering the process conditions, acetic anhydride may also be produced on the same plant. Because both methanol and carbon monoxide are commodity raw materials, methanol carbonylation long appeared to be an attractive method for acetic acid production. Henry Drefyus at British Celanese developed a methanol carbonylation pilot plant as early as 1925.[10] However, a lack of practical materials that could contain the corrosive reaction mixture at the high pressures needed (200 atm or more) discouraged commercialisation of these routes for some time. The first commercial methanol carbonylation process, which used a cobalt catalyst, was developed by German chemical company BASF in 1963. In 1968, a rhodium-based catalyst (cis−[Rh(CO)2I2]−) was discovered that could operate efficiently at lower pressure with almost no by-products. The first plant using this catalyst was built by U.S. chemical company Monsanto in 1970, and rhodium-catalysed methanol carbonylation became the dominant method of acetic acid production (see Monsanto process). In the late 1990s, the chemicals company BP Chemicals commercialised the Cativa catalyst ([Ir(CO)2I2]−), which is promoted by ruthenium. This iridium-catalysed process is greener and more efficient[11] and has largely supplanted the Monsanto process, often in the same production plants.

Acetaldehyde oxidation

Prior to the commercialisation of the Monsanto process, most acetic acid was produced by oxidation of acetaldehyde. This remains the second most important manufacturing method, although it is uncompetitive with methanol carbonylation. The acetaldehyde may be produced via oxidation of butane or light naphtha, or by hydration of ethylene.

When butane or light naphtha is heated with air in the presence of various metal ions, including those of manganese, cobalt and chromium, peroxides form and then decompose to produce acetic acid according to the chemical equation

Typically, the reaction is run at a combination of temperature and pressure designed to be as hot as possible while still keeping the butane a liquid. Typical reaction conditions are 150 °C and 55 atm. Several side products may also form, including butanone, ethyl acetate, formic acid, and propionic acid. These side products are also commercially valuable, and the reaction conditions may be altered to produce more of them if this is economically useful. However, the separation of acetic acid from these by-products adds to the cost of the process.

Under similar conditions and using similar catalysts as are used for butane oxidation, acetaldehyde can be oxidised by the oxygen in air to produce acetic acid

Using modern catalysts, this reaction can have an acetic acid yield greater than 95%. The major side products are ethyl acetate, formic acid, and formaldehyde, all of which have lower boiling points than acetic acid and are readily separated by distillation.

Ethylene oxidation

Fermentation

- Oxidative fermentation

For most of human history, acetic acid, in the form of vinegar, has been made by bacteria of the genus Acetobacter. Given sufficient oxygen, these bacteria can produce vinegar from a variety of alcoholic foodstuffs. Commonly used feeds include apple cider, wine, and fermented grain, malt, rice, or potato mashes. The overall chemical reaction facilitated by these bacteria is

A dilute alcohol solution inoculated with Acetobacter and kept in a warm, airy place will become vinegar over the course of a few months. Industrial vinegar-making methods accelerate this process by improving the supply of oxygen to the bacteria.

The first batches of vinegar produced by fermentation probably followed errors in the winemaking process. If must is fermented at too high a temperature, acetobacter will overwhelm the yeast naturally occurring on the grapes. As the demand for vinegar for culinary, medical, and sanitary purposes increased, vintners quickly learned to use other organic materials to produce vinegar in the hot summer months before the grapes were ripe and ready for processing into wine. This method was slow, however, and not always successful, as the vintners did not understand the process.

One of the first modern commercial processes was the "fast method" or "German method," first practised in Germany in 1823. In this process, fermentation takes place in a tower packed with wood shavings or charcoal. The alcohol-containing feed is trickled into the top of the tower, and fresh air supplied from the bottom by either natural or forced convection. The improved air supply in this process cut the time to prepare vinegar from months to weeks.

Most vinegar today is made in submerged tank culture, first described in 1949 by Otto Hromatka and Heinrich Ebner. In this method, alcohol is fermented to vinegar in a continuously stirred tank, and oxygen is supplied by bubbling air through the solution. Using this method, vinegar of 15 percent acetic acid can be prepared in only two to three days.

- Anaerobic fermentation

Some species of anaerobic bacteria, including several members of the genus Clostridium, can convert sugars to acetic acid directly, without using ethanol as an intermediate. The overall chemical reaction conducted by these bacteria may be represented as:

- C6H12O6 → 3 CH3COOH

More interestingly from the point of view of an industrial chemist, many of these acetogenic bacteria can produce acetic acid from one-carbon compounds, including methanol, carbon monoxide, or a mixture of carbon dioxide and hydrogen:

This ability of Clostridium to utilise sugars directly, or to produce acetic acid from less costly inputs, means that these bacteria could potentially produce acetic acid more efficiently than ethanol-oxidisers like Acetobacter. However, Clostridium bacteria are less acid-tolerant than Acetobacter. Even the most acid-tolerant Clostridium strains can produce vinegar of only a few per cent acetic acid, compared to some Acetobacter strains that can produce vinegar of up to 20 percent acetic acid. At present, it remains more cost-effective to produce vinegar using Acetobacter than to produce it using Clostridium and then concentrating it. As a result, although acetogenic bacteria have been known since 1940, their industrial use remains confined to a few niche applications.

Applications

Acetic acid is a chemical reagent for the production of many chemical compounds. The largest single use of acetic acid is in the production of vinyl acetate monomer, closely followed by acetic anhydride and ester production. The volume of acetic acid used in vinegar is comparatively small.

Vinyl acetate monomer

The major use of acetic acid is for the production of vinyl acetate monomer (VAM). This application consumes approximately 40 to 45 percent of the world's production of acetic acid. The reaction is of ethylene and acetic acid with oxygen over a palladium catalyst.

- 2 H3C-COOH + 2 C2H4 + O2 → 2 H3C-CO-O-CH=CH2 + 2 H2O

Vinyl acetate can be polymerised to polyvinyl acetate or to other polymers, which are applied in paints and adhesives.

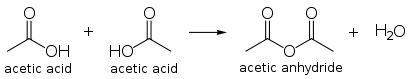

Acetic anhydride

The condensation product of two molecules of acetic acid is acetic anhydride. The worldwide production of acetic anhydride is a major application, and uses approximately 25 to 30 percent of the global production of acetic acid. Acetic anhydride may be produced directly by methanol carbonylation bypassing the acid, and Cativa plants can be adapted for anhydride production.

Acetic anhydride is a strong acetylation agent. As such, its major application is for cellulose acetate, a synthetic textile also used for photographic film. Acetic anhydride is also a reagent for the production of aspirin, heroin, and other compounds.

Vinegar

In the form of vinegar, acetic acid solutions (typically 5 to 18 percent acetic acid, with the percentage usually calculated by mass) are used directly as a condiment, and also in the pickling of vegetables and other foodstuffs. Table vinegar tends to be more dilute (5 to 8 percent acetic acid), while commercial food pickling generally employs more concentrated solutions. The amount of acetic acid used as vinegar on a worldwide scale is not large, but historically, this is by far the oldest and most well-known application.

Use as solvent

Glacial acetic acid is an excellent polar protic solvent, as noted above. It is frequently used as a solvent for recrystallisation to purify organic compounds. Pure molten acetic acid is used as a solvent in the production of terephthalic acid (TPA), the raw material for polyethylene terephthalate (PET). Although currently accounting for 5–10 percent of acetic acid use worldwide, this specific application is expected to grow significantly in the next decade, as PET production increases.

Acetic acid is often used as a solvent for reactions involving carbocations, such as Friedel-Crafts alkylation. For example, one stage in the commercial manufacture of synthetic camphor involves a Wagner-Meerwein rearrangement of camphene to isobornyl acetate; here acetic acid acts both as a solvent and as a nucleophile to trap the rearranged carbocation. Acetic acid is the solvent of choice when reducing an aryl nitro-group to an aniline using palladium-on-carbon.

Glacial acetic acid is used in analytical chemistry for the estimation of weakly alkaline substances such as organic amides. Glacial acetic acid is a much weaker base than water, so the amide behaves as a strong base in this medium. It then can be titrated using a solution in glacial acetic acid of a very strong acid, such as perchloric acid.

Other applications

Dilute solutions of acetic acids are also used for their mild acidity. Examples in the household environment include the use in a stop bath during the development of photographic films, and in descaling agents to remove limescale from taps and kettles. The acidity is also used for treating the sting of the box jellyfish by disabling the stinging cells of the jellyfish, preventing serious injury or death if applied immediately, and for treating outer ear infections in people in preparations such as Vosol. Equivalently, acetic acid is used as a spray-on preservative for livestock silage, to discourage bacterial and fungal growth.

Glacial acetic acid is also used as a wart and verruca remover. A ring of petroleum jelly is applied to the skin around the wart to prevent spread, and one to two drops of glacial acetic acid are applied to the wart or verruca. Treatment is repeated daily. This method is painless and has a high success rate, unlike many other treatments. Absorption of glacial acetic acid is safe in small amounts.

Several organic or inorganic salts are produced from acetic acid, including:

- Sodium acetate—used in the textile industry and as a food preservative (E262).

- Copper(II) acetate—used as a pigment and a fungicide.

- Aluminium acetate and iron(II) acetate—used as mordants for dyes.

- Palladium(II) acetate—used as a catalyst for organic coupling reactions such as the Heck reaction.

Substituted acetic acids produced include:

- Monochloroacetic acid (MCA), dichloroacetic acid (considered a by-product), and trichloroacetic acid. MCA is used in the manufacture of indigo dye.

- Bromoacetic acid, which is esterified to produce the reagent ethyl bromoacetate.

- Trifluoroacetic acid, which is a common reagent in organic synthesis.

Amounts of acetic acid used in these other applications together (apart from TPA) account for another 5–10 percent of acetic acid use worldwide. These applications are, however, not expected to grow as much as TPA production.

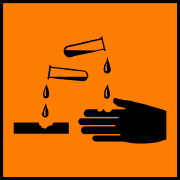

Safety

Concentrated acetic acid is corrosive and must therefore be handled with appropriate care, since it can cause skin burns, permanent eye damage, and irritation to the mucous membranes. These burns or blisters may not appear until several hours after exposure. Latex gloves offer no protection, so specially resistant gloves, such as those made of nitrile rubber, should be worn when handling the compound. Concentrated acetic acid can be ignited with some difficulty in the laboratory. It becomes a flammable risk if the ambient temperature exceeds 39 °C (102 °F), and can form explosive mixtures with air above this temperature (explosive limits: 5.4–16 percent).

The hazards of solutions of acetic acid depend on the concentration. The following table lists the EU classification of acetic acid solutions:

| Concentration by weight |

Molarity | Classification | R-Phrases |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10%–25% | 1.67–4.16 mol/L | Irritant (Xi) | R36/38 |

| 25%–90% | 4.16–14.99 mol/L | Corrosive (C) | R34 |

| >90% | >14.99 mol/L | Corrosive (C) | R10, R35 |

Solutions at more than 25 percent acetic acid are handled in a fume hood because of the pungent, corrosive vapor. Dilute acetic acid, in the form of vinegar, is harmless. However, ingestion of stronger solutions is dangerous to human and animal life. It can cause severe damage to the digestive system, and a potentially lethal change in the acidity of the blood.

See also

- Vinegar

- Acetobacter

- Carboxylic acid

- Fatty acid

- Formic acid

- Propionic acid

- Acetaldehyde

- Acetic anhydride

- Ethyl acetate

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Acetic Acid. NIST. Retrieved April 3, 2018.

- ↑ Geoffrey Martin, Industrial and Manufacturing Chemistry, Part 1, Organic (London: Crosby Lockwood, 1917), 330–331.

- ↑ Helmut Schweppe, "Identification of dyes on old textiles," J. Am. Inst. Conservation 19(1) (1979): 14–23. Retrieved April 3, 2018.

- ↑ R. E. Jones and D. H. Templeton, "The crystal structure of acetic acid." Acta Crystallogr. 11(7) (1958): 484–487.

- ↑ James M. Briggs, Toan B. Nguyen, and William L. Jorgensen, "Monte Carlo simulations of liquid acetic acid and methyl acetate with the OPLS potential functions," J. Phys. Chem. 95 (1991): 3315-3322.

- ↑ James B. Togeas, "Acetic Acid Vapor: 2. A Statistical Mechanical Critique of Vapor Density Experiments," J. Phys. Chem. A 109 (2005): 5438-5444. Digital object identifier (DOI): 10.1021/jp058004j

- ↑ John Buckingham and Fiona Macdonald (eds.), Dictionary of Organic Compounds, 6th Ed. Vol. 1. (London: Chapman and Hall, 1995, ISBN 978-0849300073).

- ↑ Noriyki Yoneda, Satoru Kusano, Makoto Yasui, Peter Pujado, and Steve Wilcher, Appl. Catal. A: Gen. 221 (2001): 253–265.

- ↑ "Production report." Chem. Eng. News (July 11, 2005), 67–76.

- ↑ Frank S. Wagner, "Acetic acid." Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology, 3rd edition, edited by Martin Grayson, (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1978).

- ↑ Mike Lancaster, Green Chemistry, an Introductory Text. (Cambridge: Royal Society of Chemistry, 2002, ISBN 0854046208), 262–266.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Agreda, Victor H., and Joseph R. Zoeller (eds.). Acetic Acid and Its Derivatives. CRC Press, 1992. ISBN 0824787927.

- Bloch, D.R. Organic Chemistry Demystified. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2006. ISBN 0071459200.

- Buckingham, John, and Fiona Macdonald (eds.). Dictionary of Organic Compounds, 6th Ed. London: Chapman and Hall, 1995. ISBN 978-0849300073.

- Grayson, Martin (ed.). Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology, 3rd edition. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1978.

- Lancaster, Mike. Green Chemistry, an Introductory Text. Cambridge: Royal Society of Chemistry, 2002. ISBN 0854046208.

- Martin, Geoffrey. Industrial and Manufacturing Chemistry, Part 1, Organic. London: Crosby Lockwood, 1917.

- McMurry, John. Organic Chemistry, 6th ed. Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole, 2004. ISBN 0534420052.

- Morrison, Robert T., and Robert N. Boyd. Organic Chemistry, 6th ed. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1992. ISBN 0136436692.

- Solomons, T.W. Graham, and Craig B. Fryhle. Organic Chemistry, 8th ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley, 2004. ISBN 0471417998.

External links

All links retrieved June 14, 2023.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.