| Ho-Chunk |

|---|

|

| Total population |

| 7,000 - 10,000 |

| Regions with significant populations |

| United States (Iowa, Nebraska, Wisconsin) |

| Languages |

| English, Hocąk |

| Religions |

| Christianity, other |

| Related ethnic groups |

| Ioway, Omaha, and other Siouan peoples |

Ho-Chunk or Winnebago (as they are commonly called) are a tribe of Native Americans, native to what are now Wisconsin and Illinois. The term "Winnebago" originally came from a name given to them by neighboring Algonquian tribes, which meant something like "people of the stagnant water" (c.f. Ojibwe: Wiinibiigoo), though the exact translation is disputed. The French called them the Puans, translated into English as "Stinkards," based on the information given by rival groups of natives. The more correct, but less common English name for the tribe is "Ho-Chunk," from their original native name Hotcâŋgara, meaning "big fish people" [1] The big fish in this case is probably sturgeon, once abundant in Lake Winnebago.

The Winnebago were farmers of corn, hunters and fishers, who believed in spiritual beings and a reverence for nature. They had rituals dedicated to war, and were quite dangerous enemies. They were involved in the Winnebago War in 1827 and the Black Hawk War of 1832. Contemporary Ho-Chunk live in primarily in Wisconsin, as the Ho-Chunk Sovereign Nation. Another group, known as the Winnebago tribe, has a reservation in Nebraska that extends into Iowa.

Language

The Ho-Chunk language is part of the Siouan language family, and is closely related to the languages of the Iowa, Missouri, and Oto. Although the language is highly endangered, there are vigorous efforts underway to keep it alive, primarily through the Hocąk Wazija Haci Language Division.

The language can be written using the "Pa-Pe-Pi-Po" syllabics, although as of 1994 the official orthography of the Ho-Chunk Nation is an adaptation of the Roman alphabet. The current official orthography derives from an Americanist version of the International Phonetic Alphabet. As such its graphemes broadly resemble those of IPA, and there is a close one-to-one correspondence between graphemes and phonemes.

History

The written history of the Ho-Chunk/Winnebago begins with the records made from the reports of Jean Nicolet, who was the first white man to establish contact with this people in 1634. At that time the Winnebago/Ho-Chunk occupied the area around Green Bay in Wisconsin, reaching beyond Lake Winnebago to the Wisconsin River and to the Rock River in Illinois. The tribe traditionally practiced corn agriculture in addition to hunting. They were not advanced in agriculture but living on Green Bay they would fish, collect wild rice, gather sugar from maple trees, and would hunt game.

Although their Siouan language indicates either contact or common origin with the other peoples of this language group, the oral traditions of the Ho-Chunk/Winnebago speak of no other homeland other than what is now large portions of Wisconsin, Iowa, and Minnesota. These traditions suggest that they were a very populous people, and the dominant group in Wisconsin in the century before Nicolet's visit. While their language was Siouan, their culture was very similar to the Algonquian peoples. Current elders suggest that their pre-history is connected to the mound builders of the region.[2] The oral history also indicates that in the mid-1500s, the influx of Ojibwa peoples in the northern portion of their range caused some movement to the south and some friction with the Illinois, as well as a division of the people as the Chiwere group (Iowa, Missouri, Ponca, and Oto tribes) moved west because the reduced range made it difficult to sustain such a large population.[3]

Nicolet reported a gathering of approximately 5,000 warriors as the Ho-Chunk/Winnebago entertained him, and so estimates of their total population range from 8,000 to more than 20,000 in 1634. Between that time and the first return of French trappers and traders in the late 1650s, the written history of the Ho-Chunk/Winnebago is virtually a blank page. What is known, however, is that in that time period the population was reduced drastically, with some reporting it dropped below a total of only 500 people. The result of this was the loss of dominance in the region, which enabled the influx of numerous Algonquian tribes as they were fleeing the problems caused by the Iroquois in the Beaver Wars.

The reasons given for this drop in population vary, but three causes are repeatedly referred to and it is likely that all three played a part. The first is the loss of several hundred warriors in a storm on a lake in the course a military effort.[4] One report says it happened on Lake Michigan after repulsing the first wave of Potawatomi from what is now Door County, Wisconsin.[5] Another says it was 500 lost in a storm on Lake Winnebago during a failed campaign against the Fox,[6] while still another says it was in a battle against the Sauk.[7]

It is unlikely that such a loss could by itself result in the near decimation of the whole people, and other causes should be included.[8] The Winnebago during this time apparently also suffered greatly from a disease, perhaps one of the European plagues like smallpox (although the Winnebago say it resulted in the victims turning yellow, which is not a trait of smallpox).[3] Finally, it appears that a sizable contingent of their historic enemies, the Illinois, came on a mission of mercy to help the Winnebago at time of suffering and famine - what one might expect after the loss of 600 men who were also their hunters. Perhaps remembering former hostilities, however, the Winnebago repaid the kindness by adding their benefactors to their diet. The Illinois were enraged and in the ensuing retaliation they almost totally wiped out the Winnebago. With reasonable speculation, one might conclude there is a connection between the loss of 600 warriors and the origin of the name of Porte des Morts at the tip of Door County, Wisconsin. After peace was established between the French and Iroquois in 1701, many of the Algonquian people returned to their homelands and the Ho-Chunk/Winnebago once again had access to their traditional lands.

From a low of, perhaps, less than 500, the population of the people gradually recovered, aided by intermarriage with neighboring tribes and even with some of the French traders. A count from 1736 gives a population of 700. In 1806, they numbered 2,900 or more. A census in 1846 reported 4,400, but in 1848 the number given is only 2,500. With other native Americans, the Ho-Chunk/Winnebago were affected by the smallpox epidemics of 1757-1758 and 1836, in the latter of which one out of four died.[3] Today the total population of Ho-Chunk/Winnebago people is about 12,000.

Glory of the Morning (Hoe-poe-kaw in Ho-chunk) was the first woman ever described in the written history of Wisconsin. She became chief of the Ho-Chunk tribe in the year 1727, when she was 18. In 1728 she married a French fur trader named Sabrevoir Descaris. During the time she was chief, the Ho-Chunk and their French trading partners were being harassed by the Fox tribe. Under Glory of the Morning's leadership, the Ho-Chunk allied themselves with the French and fought the Fox tribe in several battles during the 1730s and 1740s.

Red Bird was a war chief of the Ho-Chunk. He was born in 1788 and his name derived from the two preserved red birds that he wore as badges on each shoulder. He was a leader in the Winnebago War against the United States, which began when two of his tribesmen were unjustly punished by the government. He attacked white settlers in the area of Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin, and was soon captured, brought to trial, and imprisoned. He died while in prison in 1828.

Yellow Thunder (Ho-chunk name Wahkanjahzeegah also given as Wakunchakookah, born in 1774) was a chief of the Ho-Chunk tribe. Historians state that he and his fellow chiefs were persuaded to sign their lands over to whites without realizing what they were doing. After signing over their lands, in what is now the area of Green Bay, Wisconsin, the tribe was given eight months to leave. Yellow Thunder and other chiefs traveled to Washington D.C. in 1837 to assert their claims, but President Andrew Jackson would not meet with them.

Yellow Thunder and his people refused to move, and in 1840, troops arrived to force them to do so. Yellow Thunder was briefly chained, but released, as he and his fellow chiefs realized that further resistance would lead to violence against their people and agreed to cooperate. Yellow Thunder eventually moved off the Iowa reservation and onto a 40-acre farm in Wisconsin, where he died in 1874.

The tribe at one point asked to be moved near to the Oto tribe but were not accommodated.

Through a series of moves imposed by the U.S. government in the nineteenth century, the tribe was moved to reservations in Wisconsin, Minnesota, South Dakota, and finally in Nebraska. Through these moves, many tribe members returned to previous homes, especially to Wisconsin despite repeated roundups and removals. The U.S. government finally allowed the Wisconsin Winnebago to homestead land there. The Nebraska tribe members are today the separate Winnebago tribe.

Winnebago War

A treaty of peace had been signed at Prairie du Chien in Wisconsin on August 19, 1825, by the terms of which all the common boundaries between the white settlers, the Winnebago, Potawatomi, Sioux, Sauk, Fox and other tribes, were defined. While the situation remained generally tense but peaceful between settlers who arrived in Wisconsin during the lead boom and the local Native Americans, violence eventually broke out. The different tribes not only commenced a warfare among themselves in regard to their respective territorial limits, but they extended their hostilities to the white settlements as response to the increasing occupation of their lands.

The Winnebago War has its immediate roots in the alleged murder of the Method family of Prairie du Chien in spring, 1826, when the family was gathering Maple syrup near the Yellow River in present day Iowa. Following the discovery of the deaths, six Winnebago men were arrested in Prairie du Chien and accused of the murders. While four of the men were soon released, two were jailed in Prairie du Chien's Fort Crawford. Later during the same year, Col. Josiah Snelling, commander of Fort Snelling, Minnesota, ordered the garrison at Fort Crawford to relocate to Fort Snelling, leaving Prairie du Chien undefended by federal troops. During the relocation, the two Winnebago prisoners were also moved to Fort Snelling, but misinformation spread among the Winnebago that the men had been killed. This further heightened the tensions between the Winnebago and the white settlers of southwest Wisconsin.

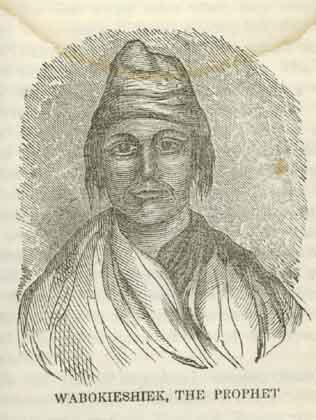

On June 27, 1827, a band of Winnebago led by war chief Red Bird and a Prophet called White Cloud (Wabokieshiek, who would later have an important role in the events surrounding the Black Hawk War) entered Prairie du Chien seeking revenge for what they believed were the executions of the Winnebago prisoners by the U.S. Army. Red Bird, White Cloud, and their followers first entered the home of local merchant James Lockwood, but finding him not home, they proceeded to the home of Registe Gagnier, a few miles southwest of Prairie du Chien. The Gagnier family knew Red Bird, and welcomed him and his companions into the house, offering them a meal. Soon, though, the Winnebago men turned violent. They first shot Rigeste Gagnier, and then turned their attention towards Solomon Lipcap, a hired man who was working in a garden outside the home. Gagnier's wife took this opportunity to take her three year old son and flee to the home of a neighbor. Still inside the house was the Gagnier's one year old daughter. After the Winnebagos had succeeded in killing and scalping both Rigeste Gagnier and Solomon Lipcap, they returned to the house and found the infant, whom they scalped and left for dead. Then they quickly fled the scene, for an alarm had been raised in the town and a crowd of men were on their way to the house. By the time they arrived, Red Bird and his companions were long gone. Remarkably, the infant girl was found alive, and she was brought to the village to recover.

Following these murders at Prairie du Chien, widespread fear spread among white settlers in the region, and a volunteer militia was formed to protect the town against further attack. Meanwhile, Red Bird and his men went north to what is now La Crosse, Wisconsin. In early July, they attacked two keel-boats carrying supplies to Fort Snelling up the Mississippi River, killing two of the crew and wounding four white men. Seven Winnebago also perished in the attack. A series of further attacks against the local white population ensued. Red Bird and his followers killed some settlers along the lower Wisconsin River and struck the lead mines near Galena. Several members of other local tribes joined the actions, including the Potawatomi and the Sauk.

Over the next two months, Lewis Cass, the governor of Michigan Territory, ordered the mustering of troops and militias to prepare the meet the Winnebago. The force began its way up the Wisconsin River towards Portage, Wisconsin, hoping that the show of force would force the Winnebago to surrender.

On September 27, the uprising came to an end before the arrival of the American troops in Indian country when Red Bird, White Cloud, and five other leading warriors surrendered in Portage, rather than facing the threat of open warfare with the U. S. military. Red Bird died while in confinement and a few local leaders who had taken part in the actions were executed on December 26. White Cloud and other chiefs and warriors, including Black Hawk, were pardoned by the President and released. Later, in August, 1828, in a treaty signed at Green Bay the Winnebago (along with other tribes) ceded northern Illinois for $540,000.

The general sense of unease among the local Native American population was severely increased due to the Winnebago War and the treaty that was forced upon the tribe afterwards. The hostilities, as well as the surmounting immigration of white settlers that ensued, made the possibilities of reaching a peaceful agreement extremely difficult. The resulting tension inevitably led to another armed conflict, the Black Hawk War of 1832, this time with the neighboring Sauk and Fox, and in which many members of the local tribes who had been involved at the Winnebago War would take part.

Culture

The Winnebago culture was comprised of three basic facets: the antiquated culture (dating back to before 1000 C.E.), a hefty portion of cultural borrowing from the Central Algonquian tribes sometime right after 1400, and several cultural adaptations of Christianity which started in the mid-seventeenth century.

The Winnebago believed in a vast amount of spirits, some lesser, others vitally revered, and many depicted as animals and supernatural beings with animal features. These spirits were considered to be shape-shifters, and could assume the physical manifestation of any sentient or non-sentient object. The superstitious Winnebago made offerings of small game, tools, decorations, food, feathers, bones, and tobacco. Earthmaker was the supreme being, and goes back to the earliest Winnebago beliefs, although it is believed that the concept of Earthmaker was later influenced by seventeenth century European Christian missionaries.

Every child in a Winnebago village would traditionally fast between the ages of nine and eleven, preparing for a more spiritually-heightened sense of awakening, and to form a closer bond with their personal guardian spirit, upon whom they could call upon throughout life. According to this Native American philosophy, without the aid of a guardian spirit, humans were completely at the mercy of natural, societal, and supernatural events. Visions were often granted to those who fasted the most, and certain children were chosen for a shamanic path from an early age.

The three basic types of ritual consisted of those performed by certain individuals who had all shared the same vision, those which were only in a specific clan, and those whose membership was based upon personal merit and achievement, other than warring efforts. The latter was known as the Medicine Rite.

The Warbundle Rite (or Feast) was presided over by both the Thunderbird and the Night Spirits. All Winebago spirits were present however, and acknowledged accordingly through rituals, sacrifices, and offerings. The Warbundle ritual was dedicated to glorifying war and conquest, and though many warring deities were worshiped during this ceremony, many pacifist spirits were also revered, such as the Earthmaker, Earth, Moon, and Water. The Turtle and the Hare were considered to be hero-deities. One other noteworthy deity includes Kokopelli, the humpbacked god worshiped in many tribes and usually depicted playing his war flute.

The warbundle was a possession prized above all others, and its contents consisted of a deerskin wrap, containing a superstitious and practical bundle of assorted objects. Typical findings in a Winnebago warbundle could include anything from the rotting corpse of an eagle or black hawk, a snake skin, wolf and deer tails, war-clubs, feathers, flutes, and medicinal paint (warpaint with topical and subdermal hallucinogenic properties). It was believed that when the paint was smeared over the body, the warrior would become invisible and impervious to fatigue, and that if the flutes were blown during a fight, the powers of fight and flight would be annihilated in their enemies, making them easy prey for the wrath of the war-clubs. The warbundles were carefully concealed and approached, because of the supernatural energy associated with it, and the only thing that could vanquish its powers was contact with menstrual blood.

Contemporary Winnebago

As of 2003 there are two Ho-Chunk/Winnebago tribes officially recognized by the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs: The Ho-Chunk Nation of Wisconsin (formerly the Wisconsin Winnebago Tribe) and the Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska (Thurston County, Nebraska, and Woodbury County, Iowa).

Ho-Chunk Sovereign Nation

The tribe located primarily in Wisconsin changed its official name in 1994 to the Ho-Chunk Sovereign Nation (meaning People of the Big Voice). There were 6,159 tribe members as of 2001. The tribe does not have a formal reservation; however, the tribe owns 4,602 acres (18.625 km²) scattered across parts of 12 counties in Wisconsin and one county in Minnesota. The largest concentrations are in Jackson County, Clark County, and Monroe County in Wisconsin. Smaller areas lie in Adams, Crawford, Dane, Juneau, La Crosse, Marathon, Sauk, Shawano, and Wood Counties in Wisconsin, as well as Houston County, Minnesota. The administrative center is in Black River Falls, Wisconsin, in Jackson County. The tribe also operates several casinos.

Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska

Through a series of moves imposed by the U.S. government in the nineteenth century, the Winnebago were relocated to reservations in Wisconsin, Minnesota, South Dakota and finally in Nebraska. Through these moves, many tribe members returned to previous homes, especially to Wisconsin, despite repeated roundups and removals. The U.S. government finally allowed the Wisconsin Winnebago to homestead land there. The Nebraska tribe members are today the separate Winnebago tribe.

The tribe has a reservation in northeastern Nebraska and western Iowa. The Winnebago Indian Reservation lies primarily in the northern part of Thurston County, but small parts extend into southeastern Dixon County and Woodbury County, Iowa. There is even a small plot of off-reservation land of 116.75 acres in southern Craig Township in Burt County, Nebraska. The total land area is 457.857 km² (176.78 sq mi). The 2000 census reported a population of 2,588 persons living on these lands. The largest community is the village of Winnebago.

The Omaha also has a reservation in Thurston County. Together, both tribes cover the whole land area of Thurston County. The Winnebago tribe operates the WinnaVegas Casino in the Iowa portion of the reservation. This land was west of the Missouri, but due to the U.S Army Corp. of Engineers channeling the Missouri, changing the course of the Missouri River, the reservation land was divided into Iowa and Nebraska. So, although the state of Iowa is east of the Missouri River, the tribe successfully argued that this land belonged to them under the terms of a predated deed. This land has a postal address of Sloan, Iowa, as rural addresses are normally covered by the nearest post office.

Famous Ho-Chunk People

- Glory of the Morning

- Hononegah

- Mountain Wolf Woman

- Red Bird

- Mitchell Red Cloud, Jr.

- Chief Waukon Decorah

- Yellow Thunder

Notes

- ↑ Paul Radin. The Winnebago Tribe. (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1990), 5

- ↑ Ho Chunk: People of the Sacred Language Ho-Chunk Nation. Retrieved October 13, 2007.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Winnebago History dickshovel.com. Retrieved October 13, 2007.

- ↑ Carol I. Mason. Introduction to Wisconsin Indians. (Salem, WI: Sheffield Publishing Co.), 66

- ↑ R. David Edmunds. The Potawatomis: Keepers of the Fire. (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1978), 5

- ↑ Lee Sultzman Potawatomi History tolatsga.org. Retrieved October 13, 2007.

- ↑ James A. Clifton. The Prairie People: Continuity and Change in Potawatomi Indian Culture 1665-1965. (Lawrence, KS: The Regents Press of Kansas, 1977), 37

- ↑ Edmunds, 5

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Clifton, James A. The Prairie People: Continuity and Change in Potawatomi Indian Culture, 1665-1965. University of Iowa Press, 1998. ISBN 978-0877456445

- Diedrich, Mark. Ho-Chunk Chiefs. Coyote Books, 2001. ISBN 978-1892415028

- Edmunds, R. David. The Potawatomis: Keepers of the Fire. University of Oklahoma Press, 1987. ISBN 978-0806120690

- Mason, Carol I. Introduction to Wisconsin Indians: Prehistory to Statehood. Sheffield Publishing Co., 1988. ISBN 978-0881333084

- Radin, Paul. The Winnebago Tribe. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1990. ISBN 0803257104

- Smith, David Lee. Folklore of the Winnebago Tribe. University of Oklahoma Press, 1997. ISBN 978-0806129761

- Waldman, Carl. Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes. Checkmark Books, 2006. ISBN 978-0816062744

External links

All links retrieved May 15, 2023.

- Ho-Chunk Nation web site

- The Encyclopedia of Hotcâk (Winnebago) Mythology

- Catholic Encyclopedia entry

- Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska

- Paul Radin's Winnebago Notebooks at the American Philosophical Library

- First Nations Histories: Winnebago

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Ho-Chunk history

- Winnebago_language history

- Ho-Chunk_mythology history

- Winnebago_War history

- Yellow_Thunder history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.