| Term of office | January 20, 1961 â November 22, 1963 |

| Preceded by | Dwight D. Eisenhower |

| Succeeded by | Lyndon B. Johnson |

| Date of birth | May 29, 1917 |

| Place of birth | Brookline, Massachusetts |

| Date of death | November 22 1963 (aged 46) |

| Place of death | Dallas, Texas |

| Spouse | Jacqueline Lee Bouvier Kennedy |

| Political party | Democratic |

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917âNovember 22, 1963), was the thirty-fifth President of the United States, serving from 1961 until his assassination in 1963.

After Kennedy's leadership as commander of the USS PT-109 during World War II in the South Pacific, his aspirations turned political. Kennedy represented Massachusetts in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1947 to 1953 as a Democrat, and in the U.S. Senate from 1953 until 1961. Kennedy defeated former Vice President and Republican candidate Richard Nixon in the 1960 U.S. presidential election, one of the closest in American history. He was the first practicing Roman Catholic to be elected President and the first to have won a Pulitzer Prize. His administration witnessed the Bay of Pigs Invasion, the Cuban Missile Crisis, the building of the Berlin Wall, the space race, the Civil Rights Movement and early events of the Vietnam War.

Kennedy was assassinated on November 22, 1963, in Dallas, Texas. With the murder two days later of the prime suspect, Lee Harvey Oswald, the circumstances surrounding the death of Kennedy have been controversial. The event proved to be a poignant moment in U.S. history due to its impact on the nation and the ensuing political fallout.

Kennedy was not perfect. There are considerable allegations about womanizing and some controversy related to the counting of votes in Chicago for his election as President. However, many regard him as an icon of American hopes and aspirations. Kennedy continues to rank highly in public opinion ratings of former U.S. presidents.

Early life and education

John Fitzgerald Kennedy was born in Brookline, Massachusetts on May 29, 1917, the second son of Joseph P. Kennedy, Sr., and Rose Fitzgerald. Kennedy lived in Brookline for his first ten years. He attended Brookline's public Edward Devotion School from kindergarten through the beginning of third grade, then Noble and Greenough Lower School and its successor, the Dexter School, a private school for boys, through fourth grade. In September 1927, Kennedy moved with his family to a rented 20-room mansion in Riverdale, Bronx, New York City, then two years later moved to a six-acre estate in Bronxville, New York. He was a member of Scout Troop 2 at Bronxville from 1929 to 1931 and was to be the first Scout to become President.[1] Kennedy spent summers with his family at their home in Hyannisport, Massachusetts and Christmas and Easter holidays with his family at their winter home in Palm Beach, Florida.

He graduated from the Choate School in June 1935. Kennedy's superlative in his yearbook was "Most likely to become President." In September 1935, he sailed on the SS Normandie on his first trip abroad with his parents and his sister Kathleen to London with the intent of studying for a year with Professor Harold Laski at the London School of Economics as his older brother Joe had done, but after a brief hospitalization with jaundice after less than a week at LSE, he sailed back to America only three weeks after he had arrived. In October 1935, Kennedy enrolled late and spent six weeks at Princeton University, but was then hospitalized for two months observation for possible leukemia in Boston in January and February 1936, recuperated at the Kennedy winter home in Palm Beach in March and April, spent May and June working as a ranch hand on a 40,000 acre (160 km²) cattle ranch outside Benson, Arizona, then July and August racing sailboats at the Kennedy summer home in Hyannisport.

In September 1936 he enrolled as a freshman at Harvard College, again following two years behind his older brother Joe. In early July 1937, Kennedy took his convertible, sailed on the SS Washington to France, and spent ten weeks driving with a friend through France, Italy, Germany, Holland and England. In late June 1938, Kennedy sailed with his father and brother Joe on the SS Normandie to spend July working with his father, recently appointed U.S. Ambassador to the United Kingdom by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, at the American embassy in London, and August with his family at a villa near Cannes. From February through September 1939, Kennedy toured Europe, the Soviet Union, the Balkans and the Middle East to gather background information for his Harvard senior honors thesis. He spent the last ten days of August in Czechoslovakia and Germany before returning to London on September 1, 1939, the day Germany invaded Poland. On September 3, 1939, Kennedy, along with his brother Joe, his sister Kathleen, and his parents were in the Strangers Gallery of the House of Commons to hear speeches in support of the United Kingdom's declaration of war on Germany. Kennedy was sent as his father's representative to help with arrangements for American survivors of the SS Athenia, before flying back to the U.S. on his first transatlantic flight at the end of September.

In 1940, Kennedy completed his thesis, "Appeasement in Munich," about British participation in the Munich Agreement. He initially intended his thesis to be private, but his father encouraged him to publish it as a book. He graduated cum laude from Harvard with a degree in international affairs in June 1940, and his thesis was published in July 1940 as a book entitled Why England Slept.[2]

From September to December 1940, Kennedy was enrolled and audited classes at the Stanford University Graduate School of Business. In early 1941, he helped his father complete the writing of a memoir of his three years as ambassador. In May and June 1941, Kennedy traveled throughout South America.

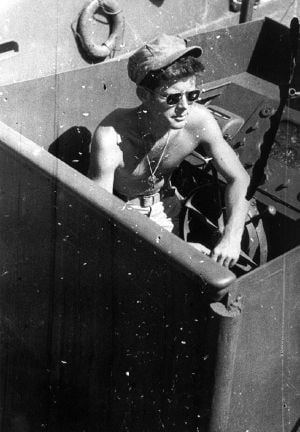

Military service

In the spring of 1941, Kennedy volunteered for the U.S. Army, but was rejected, mainly because of his troublesome back. Nevertheless, in September of that year, the U.S. Navy accepted him, due to the influence of the director of the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI), a former naval attachĂŠ to the Ambassador, his father. As an ensign, Kennedy served in the office which supplied bulletins and briefing information for the Secretary of the Navy. It was during this assignment that the attack on Pearl Harbor occurred. He attended the Naval Reserve Officers Training School and Motor Torpedo Boat Squadron Training Center before being assigned for duty in Panama and eventually the Pacific theater. He participated in various commands in the Pacific theater and earned the rank of lieutenant, commanding a patrol torpedo (PT) boat.

On August 2, 1943, Kennedy's boat, the PT-109, was taking part in a nighttime patrol near New Georgia in the Solomon Islands. in the course of action, it was rammed by the Japanese destroyer Amagiri.[3] Kennedy was thrown across the deck, injuring his already-troubled back. Nonetheless, he swam, towing a wounded man, to an island and later to a second island where his crew was subsequently rescued. For these actions, Kennedy received the Navy and Marine Corps Medal under the following citation:

| â | For extremely heroic conduct as Commanding Officer of Motor Torpedo Boat 109 following the collision and sinking of that vessel in the Pacific War Theater on August 1-2, 1943. Unmindful of personal danger, Lieutenant (then Lieutenant, Junior Grade) Kennedy unhesitatingly braved the difficulties and hazards of darkness to direct rescue operations, swimming many hours to secure aid and food after he had succeeded in getting his crew ashore. His outstanding courage, endurance and leadership contributed to the saving of several lives and were in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service. | â |

Kennedy's other decorations in World War II included the Purple Heart, Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal and the World War II Victory Medal. He was honorably discharged in early 1945, just a few months before Japan surrendered. The incident was popularized when he became president and would be the subject of several magazine articles, books, comic books, TV specials and a feature length movie, making the PT-109 one of the most famous U.S. Navy ships of the war. The coconut which was used to scrawl a rescue message given to Solomon Islander scouts who found him was kept on his presidential desk and is still at the John F. Kennedy Library.

During his presidency, Kennedy privately admitted to friends that he didn't feel that he deserved the medals he had received, because the PT-109 incident had been the result of a botched military operation that had cost the lives of two members of his crew. When asked by a reporter how he became a war hero, Kennedy joked: "It was involuntary. They sank my boat."

Early political career

After World War II, John Fitzgerald Kennedy considered becoming a journalist before deciding to run for political office. Prior to the war, he had not really considered becoming a politician because the family had already pinned its political hopes on his older brother, Joseph P. Kennedy, Jr. Joseph, however, was killed in World War II, making John the eldest brother. When in 1946 U.S. Representative James Michael Curley vacated his seat in an overwhelmingly Democratic district to become mayor of Boston, Kennedy ran for the seat, beating his Republican opponent by a large margin. He was a congressman for six years but had a mixed voting record, often diverging from President Harry S. Truman and the rest of the Democratic Party. In 1952, he defeated incumbent Republican Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr. for the U.S. Senate.

Kennedy married Jacqueline Lee Bouvier on September 12, 1953. He underwent several spinal operations over the following two years, nearly dying (in all he received the Catholic Church's "last rites" four times during his life), and was often absent from the Senate. During his convalescence, he wrote Profiles in Courage, a book describing eight instances in which U.S. Senators risked their careers by standing by their personal beliefs. The book was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Biography in 1957.[4]

In 1956, presidential nominee Adlai Stevenson left the choice of a vice presidential nominee to the Democratic convention, and Kennedy finished second in that balloting to Senator Estes Kefauver of Tennessee. Despite this defeat, Kennedy received national exposure from that episode that would prove valuable in subsequent years. His father, Joseph Kennedy, Sr., pointed out that it was just as well that John did not get that nomination, as some people sought to blame anything they could on Catholics, even though it was privately known that any Democrat would have trouble running against Eisenhower in 1956.

John F. Kennedy voted for final passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1957 after having earlier voted for the "Jury Trial Amendment," which effectively rendered the Act toothless because convictions for violations could not be obtained. Staunch segregationists such as senators James Eastland and John McClellan and Mississippi Governor James Coleman were early supporters of Kennedy's presidential campaign.[5] In 1958, Kennedy was re-elected to a second term in the United States Senate, defeating his Republican opponent, Boston lawyer Vincent J. Celeste, by a wide margin.

Years later it was revealed that in September 1947 when he was 30 years old and during his first term as a congressman, Kennedy had been diagnosed with Addison's disease, a rare endocrine disorder. The nature of this and other medical problems were kept secret from the press and public throughout Kennedy's lifetime.[6]

Republican Senator Joseph McCarthy was a friend of the Kennedy family: Joe Kennedy was a leading McCarthy supporter; Robert F. Kennedy worked for McCarthy's subcommittee, and McCarthy dated Patricia Kennedy. In 1954, when the Senate was poised to condemn McCarthy, John Kennedy drafted a speech calling for McCarthy's censure, but never delivered it. When on December 2, 1954, the Senate rendered its highly publicized decision to censure McCarthy, Senator Kennedy was in the hospital. Though absent, Kennedy could have "paired" his vote against that of another senator, but chose not to; neither did he ever indicate then nor later how he would have voted. The episode seriously damaged Kennedy's support in the liberal community, especially with Eleanor Roosevelt, as late as the 1960 election.[7]

1960 presidential election

On January 2, 1960, Kennedy declared his intention to run for President of the United States. In the Democratic primary elections, he faced challenges from Senator Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota and Senator Wayne Morse of Oregon. Kennedy defeated Humphrey in Wisconsin and West Virginia and Morse in Maryland and Oregon, although Morse's candidacy is often forgotten by historians. He also defeated token opposition (often write-in candidates) in New Hampshire, Indiana and Nebraska. In West Virginia, Kennedy visited a coal mine and talked to mine workers to win their support; most people in that conservative, mostly Protestant state were deeply suspicious of Kennedy's Catholicism. His victory in West Virginia cemented his credentials as a candidate with broad popular appeal.

With Humphrey and Morse out of the race, Kennedy's main opponent at the convention in Los Angeles was Senator Lyndon B. Johnson of Texas. Adlai Stevenson, the Democratic nominee in 1952 and 1956, was not officially running but had broad grassroots support inside and outside the convention hall. Senator Stuart Symington of Missouri was also a candidate, as were several favorite sons. On July 13, 1960, the Democratic convention nominated Kennedy as its candidate for President. Kennedy asked Johnson to be his Vice Presidential running mate, despite opposition from many liberal delegates and Kennedy's own staff, including Robert Kennedy. He needed Johnson's strength in the South to win what was considered likely to be the closest election since 1916. Major issues included how to get the economy moving again, Kennedy's Catholicism, Cuba, and whether the Soviet space and missile programs had surpassed those of the U.S. To address fears that his Catholicism would impact his decision-making, he famously told the Greater Houston Ministerial Association on September 12, 1960, "I am not the Catholic candidate for President. I am the Democratic Party's candidate for President who also happens to be a Catholic. I do not speak for my Church on public mattersâand the Church does not speak for me."[8] Kennedy also brought up the point of whether one-quarter of Americans were relegated to second-class citizenship just because they were Catholic.

In September and October, Kennedy debated Republican candidate and Vice President Richard Nixon in the first televised U.S. presidential debates in U.S. history. During these programs, Nixon, nursing an injured leg and sporting "five o'clock shadow," looked tense and uncomfortable, while Kennedy appeared relaxed, leading the huge television audience to deem Kennedy the winner. Radio listeners, however, either thought Nixon had won or that the debates were a draw. Nixon did not wear make-up during the initial debate, unlike Kennedy. The debates are now considered a milestone in American political historyâthe point at which the medium of television began to play a dominant role in national politics. After the first debate Kennedy's campaign gained momentum and he pulled slightly ahead of Nixon in most polls. On November 8, Kennedy defeated Nixon in one of the closest presidential elections of the twentieth century. In the national popular vote Kennedy led Nixon by just two-tenths of one percent (49.7 percent to 49.5 percent), while in the Electoral College he won 303 votes to Nixon's 219 (269 were needed to win). Another 14 electors from Mississippi and Alabama refused to support Kennedy because of his support for the civil rights movement; they voted for Senator Harry F. Byrd, Sr. of Virginia.

Controversial Aspects

Allegations about use of mobster contacts in Chicago to fix the election result, and also about the use of his father's money during the campaign surrounded the election. However, the result was unchallenged by the Republican Party.[9]

Presidency (1961â1963)

John F. Kennedy was sworn in as the 35th President on January 20, 1961. In his famous inaugural address he spoke of the need for all Americans to be active citizens, saying, "Ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country." He also asked the nations of the world to join together to fight what he called the "common enemies of man: tyranny, poverty, disease, and war itself." In closing, he expanded on his desire for greater internationalism: "Finally, whether you are citizens of America or citizens of the world, ask of us the same high standards of strength and sacrifice which we ask of you."[10]

Foreign policy

Cuba and the Bay of Pigs Invasion

Prior to Kennedy's election to the presidency, the Eisenhower Administration created a plan to overthrow the Fidel Castro regime in Cuba. Central to such a plan, which was structured and detailed by the CIA with minimal input from the U.S. State Department, was the arming of a counter-revolutionary insurgency composed of anti-Castro Cubans.[11] U.S.-trained Cuban insurgents were to invade Cuba and instigate an uprising among the Cuban people in hopes of removing Castro from power. On April 17, 1961, Kennedy ordered the previously planned invasion of Cuba to proceed. With support from the CIA, in what is known as the Bay of Pigs Invasion, 1500 U.S.-trained Cuban exiles, called "Brigade 2506," returned to the island in the hope of deposing Castro. However, Kennedy ordered the invasion to take place without U.S. air support. By April 19, 1961, the Cuban government had captured or killed the invading exiles, and Kennedy was forced to negotiate for the release of the 1,189 survivors. The failure of the plan originated in a lack of dialog among the military leadership, a result of which was the complete lack of naval support in the face of artillery troops on the island who easily incapacitated the exile force as it landed on the beach.[11] After 20 months, Cuba released the captured exiles in exchange for $53 million worth of food and medicine. The incident was a major embarrassment for Kennedy, but he took full personal responsibility for the debacle. Furthermore, the incident made Castro wary of the U.S. and led him to believe that another invasion would occur.

Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis began on October 14, 1962, when American U-2 spy planes took photographs of a Soviet intermediate-range ballistic missile site under construction in Cuba. The photos were shown to Kennedy on October 16, 1962. America would soon be posed with a serious nuclear threat. Kennedy faced a dilemma: if the U.S. attacked the sites, it might lead to nuclear war with the U.S.S.R., but if the U.S. did nothing, it would endure the threat of nuclear weapons being launched from close range. Because the weapons were in such proximity, the U.S. might have been unable to retaliate if they were launched preemptively. Another consideration was that the U.S. would appear to the world as weak in its own hemisphere.

Many military officials and cabinet members pressed for an air assault on the missile sites, but Kennedy ordered a naval quarantine in which the U.S. Navy inspected all ships arriving in Cuba. He began negotiations with the Soviets and ordered the Soviets to remove all defensive material being built in Cuba. Without doing so, the Soviet and Cuban peoples would face naval quarantine. A week later, he and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev reached an agreement. Khrushchev agreed to remove the missiles subject to U.N. inspections if the U.S. publicly promised never to invade Cuba and quietly remove US missiles stationed in Turkey. Following this crisis, which likely brought the world closer to nuclear war than at any point before or since, Kennedy was more cautious in confronting the Soviet Union.

Latin America and communism

Arguing that "those who make peaceful revolution impossible, make violent revolution inevitable," Kennedy sought to contain communism in Latin America by establishing the Alliance for Progress, which sent foreign aid to troubled countries in the region and sought greater human rights standards in the region. He worked closely with Puerto Rico Governor Luis MuĂąoz MarĂn for the development of the Alliance of Progress, as well as in the autonomy of the island itself.

Peace Corps

As one of his first presidential acts, Kennedy created the Peace Corps. Through this program, Americans volunteered to help underdeveloped nations in areas such as education, farming, health care and construction.

Vietnam

In Southeast Asia, Kennedy followed Eisenhower's lead by using limited military action to fight the North Vietnamese communist forces led by Ho Chi Minh. Proclaiming a fight against the spread of communism, Kennedy enacted policies providing political, economic, and military support for the unstable French-installed South Vietnamese government, which included sending 16,000 military advisers and U.S. Special Forces to the area. Kennedy also agreed to the use of free-fire zones, napalm, defoliants and jet planes. U.S. involvement in the area continually escalated until regular U.S. forces were directly fighting in the Vietnam War by the Lyndon B. Johnson administration. The Kennedy Administration increased military support, but the South Vietnamese military was unable to make headway against the pro-independence Viet-Minh and Viet Cong forces. By July 1963, Kennedy faced a crisis in Vietnam. The Administration's response was to assist in the coup d'Êtat of the president of South Vietnam, Ngo Dinh Diem.[12] In 1963, South Vietnamese generals overthrew the Diem government, arresting Diem and later killing him[13] Kennedy sanctioned Diem's overthrow. One reason for the support was a fear that Diem might negotiate a neutralist coalition government which included communists, as had occurred in Laos in 1962. Dean Rusk, Secretary of State, remarked "This kind of neutralism⌠is tantamount to surrender."

It remains a point of speculation and controversy among historians whether or not Vietnam would have escalated to the point it did had Kennedy served out his full term and been re-elected in 1964.[14] Fueling this speculation are statements made by Kennedy's and Johnson's Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara that Kennedy was strongly considering pulling out of Vietnam after the 1964 election. In the documentary film The Fog of War, not only does McNamara say this, but a tape recording of Lyndon Johnson confirmed that Kennedy was planning to withdraw from Vietnam, a position Johnson stated he disapproved. Additional evidence is Kennedy's National Security Action Memorandum (NSAM) #263 on October 11, 1963 that gave the order for withdrawal of 1,000 military personnel by the end of 1963. Nevertheless, given the stated reason for the overthrow of the Diem government, such action would have been a dramatic policy reversal, but Kennedy was generally moving in a less hawkish direction in the Cold War since his acclaimed speech about world peace at American University the previous June 10, 1963.[15]

After Kennedy's assassination, President Johnson immediately reversed Kennedy's order to withdraw 1,000 military personnel with his own NSAM #273 on November 26, 1963.

West Berlin speech

At the end of World War II in 1945, Germany was divided into four zones administered by each of the allies. The Soviet built Berlin Wall divided West and East Berlin, the latter being under the control of the Soviet Union. On June 26, 1963, Kennedy visited West Berlin and gave a public speech criticizing communism. Kennedy used the construction of the Berlin Wall as an example of the failures of communism:

"Freedom has many difficulties and democracy is not perfect, but we have never had to put a wall up to keep our people in." The speech is known for its famous phrase "Ich bin ein Berliner" ("I am a Berliner").

Nearly five-sixths of the population was on the street when Kennedy said the famous phrase. He remarked to aides afterwards: "We'll never have another day like this one."[16]

Nuclear Test Ban Treaty

Troubled by the long-term dangers of radioactive contamination and nuclear weapons proliferation, Kennedy pushed for the adoption of a Limited or Partial Test Ban Treaty, which prohibited atomic testing on the ground, in the atmosphere, or underwater, but did not prohibit testing underground. The United States, the United Kingdom and the Soviet Union were the initial signatories to the treaty; Kennedy signed the treaty into law in August 1963.

Ireland

On the occasion of his visit to Ireland in 1963, President Kennedy and Irish President Ăamon de Valera agreed to form the American Irish Foundation. The mission of this organization was to foster connections between Americans of Irish descent and the country of their ancestry. Kennedy furthered these connections of cultural solidarity by accepting a grant of armorial bearings from the Chief Herald of Ireland. Kennedy had near-legendary status in Ireland, as the first person of Irish heritage to have a position of world power. Irish citizens who were alive in 1963 often have very strong memories of Kennedy's momentous visit.[17] He also visited the original cottage where previous Kennedys had lived before emigrating to America, and said: "This is where it all began âŚ"

Iraq

In 1963, the Kennedy administration backed a coup against the government of Iraq headed by General Abdel Karim Kassem, who five years earlier had deposed the Western-allied Iraqi monarchy. The C.I.A. helped the new Baath Party government in ridding the country of suspected leftists and communists. In a Baathist bloodbath, the government used lists of suspected communists and other leftists provided by the C.I.A., to systematically murder untold numbers of Iraq's educated eliteâkillings in which Saddam Hussein, later Iraq's dictator, is said to have participated. The victims included hundreds of doctors, teachers, technicians, lawyers and other professionals as well as military and political figures.[18][19]

Domestic policy

Kennedy called his domestic program the "New Frontier." It ambitiously promised federal funding for education, medical care for the elderly, and government intervention to halt the recession. Kennedy also promised an end to racial discrimination. In 1963, he proposed a tax reform which included income tax cuts, but this was not passed by Congress until 1964, after his death. Few of Kennedy's major programs passed Congress during his lifetime, although, under his successor, President Johnson, Congress did vote them through in 1964â65.

Civil rights

The turbulent end of state-sanctioned racial discrimination was one of the most pressing domestic issues of Kennedy's era. The United States Supreme Court had ruled in 1954 that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional. However, many schools, especially in southern states, did not obey the Supreme Court's judgment. Segregation on buses, in restaurants, movie theaters, public toilets, and other public places remained. Kennedy supported racial integration and civil rights, and during the 1960 campaign he telephoned Coretta Scott King, wife of the jailed Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., which perhaps drew some additional black support to his candidacy. John and U.S. Attorney General Robert Kennedy's intervention secured the early release of King from jail.[20]

In 1962, James Meredith tried to enroll at the University of Mississippi, but he was prevented from doing so by white students. Kennedy responded by sending some 400 federal marshals and 3,000 troops to ensure that Meredith could enroll in his first class. Kennedy also assigned federal marshals to protect Freedom Riders.

As President, Kennedy initially believed the grassroots movement for civil rights would only anger many Southern whites and make it even more difficult to pass civil rights laws through Congress, which was dominated by Southern Democrats, and he distanced himself from it. As a result, many civil rights leaders viewed Kennedy as non-supportive of their efforts.

On June 11, 1963, President Kennedy intervened when Alabama Governor George Wallace blocked the doorway to the University of Alabama to stop two African American students, Vivian Malone and James Hood, from enrolling. George Wallace moved aside after being confronted by federal marshals, Deputy Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach and the Alabama National Guard. That evening Kennedy gave his famous civil rights address on national television and radio.[21] Kennedy proposed what would become the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Immigration

John F. Kennedy initially proposed an overhaul of American immigration policy that later was to become the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, sponsored by Kennedy's youngest brother, Senator Edward Kennedy. It dramatically shifted the source of immigration from Northern and Western European countries towards immigration from Latin America and Asia and shifted the emphasis of selection of immigrants towards facilitating family reunification.[22] Kennedy wanted to dismantle the selection of immigrants based on country of origin and saw this as an extension of his civil rights policies.[23]

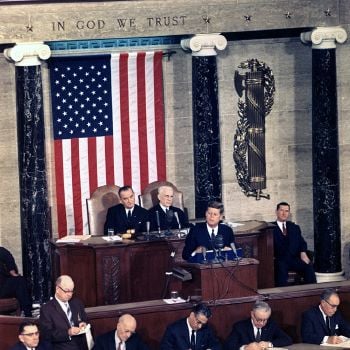

Space program

Kennedy was eager for the United States to lead the way in the space race. Sergei Khrushchev has said that Kennedy approached his father, Nikita, twice about a "joint venture" in space explorationâin June 1961 and autumn 1963. On the first occasion, Russia was far ahead of America in terms of space technology. Kennedy first made the goal for landing a man on the Moon in speaking to a Joint Session of Congress on May 25, 1961, saying

First, I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him back safely to the earth. No single space project in this period will be more impressive to mankind, or more important for the long-range exploration of space; and none will be so difficult or expensive to accomplish.[24]

Kennedy later made a speech at Rice University on September 12, 1962, in which he said

No nation which expects to be the leader of other nations can expect to stay behind in the race for space. ... We choose to go to the Moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard.[25]

On the second approach to Khrushchev, the Soviet leader was persuaded that cost-sharing was beneficial and American space technology was forging ahead. The U.S. had launched a geostationary satellite and Kennedy had asked Congress to approve more than $25 billion for the Apollo Project.

Khrushchev agreed to a joint venture in late 1963, but Kennedy died before the agreement could be formalized. On July 20, 1969, almost six years after JFK's death, Project Apollo's goal was finally realized when men landed on the Moon.

Supreme Court appointments

Kennedy appointed two Justices, Byron R. White and Arthur J. Goldberg, in 1962 to the Supreme Court of the United States.

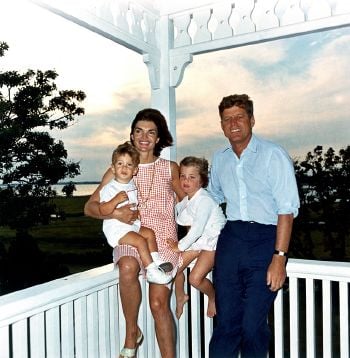

Image, social life and family

Kennedy and his wife "Jackie" were very young in comparison to earlier presidents and first ladies, and were both extraordinarily popular in ways more common to pop singers and movie stars than politicians, influencing fashion trends and becoming the subjects of numerous photo spreads in popular magazines. Jacqueline bought new art and furniture, and eventually restored all the rooms in the White House.

John F. Kennedy had two children that survived infancy. Caroline was born in 1957 and John, Jr. was born in 1960, just a few weeks after his father was elected. John died in a plane crash in 1999. Caroline is currently the only surviving member of JFK's immediate family.

Outside the White House lawn the Kennedys established a preschool, swimming pool and tree house. Jacqueline allowed very few photographs of the children to be taken but when she was gone, the President would allow the White House photographer, Cecil Stoughton, to take pictures of the children. The resulting photos are probably the most famous of the children, and especially of John, Jr., after he was photographed playing underneath the Presidentâs desk.

Behind the glamorous facade, the Kennedys also suffered many personal tragedies. Jacqueline suffered a miscarriage in 1955 and gave birth to a stillborn daughter, Arabella Kennedy, in 1956. The death of their newborn son, Patrick Bouvier Kennedy, in August 1963, was a great loss.

In October 1951, during his third term as Massachusetts 11th district congressman, the then 34-year-old Kennedy embarked on a seven-week Asian trip to Israel, India, Vietnam and Japan with his then 25-year-old brother Robert (who had just graduated from law school four months earlier) and his then 27-year-old sister Patricia. Because of their eight-year separation in age, the two brothers had previously seen little of each other. This trip was the first extended time they had spent together and resulted in their becoming best friends in addition to being brothers. Robert was campaign manager for Kennedy's successful 1952 Senate campaign and successful 1960 Presidential campaign. The two brothers worked closely together from 1957 to 1959 on the Senate Select Committee on Improper Activities in the Labor and Management Field (Senate Rackets Committee) when Robert was its chief counsel. During Kennedy's presidency, Robert served in his Cabinet as Attorney General and was his closest adviser.

Kennedy gained a reputation as a womanizer, most famously for an alleged affair with Marilyn Monroe. For some, Kennedy's association with show business personalities added to the glamor that was attached to his name. For others, this detracted from his image as a family man and role model for the next generation of American leaders.

Assassination

President Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas, Texas, at 12:30 p.m. Central Standard Time on November 22, 1963, while on a political trip through Texas. He was pronounced dead at 1:00 p.m.

Lee Harvey Oswald was arrested in a theater about 80 minutes after the assassination and charged by Dallas police for the murder of Dallas policeman, J. D. Tippit, before eventually being charged for the murder of Kennedy. Oswald denied shooting anyone, claiming he was a patsy, and two days later was killed by Jack Ruby before he could be indicted or tried.

On November 29, 1963, President Lyndon B. Johnson created the Warren Commissionâchaired by Chief Justice Earl Warrenâto investigate the assassination. After a ten-month investigation, the commission concluded that Oswald was the lone assassin. However, this remains widely disputed by some scholars and eyewitnesses of the assassination. Contrary to the Warren Commission, the United States House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA) in 1979 concluded that President Kennedy was probably assassinated as a result of a conspiracy.[26] The HSCA did not identify any additional gunmen or groups involved in the conspiracy.

Although the conclusions of the Warren Commission were initially supported by the American public, opinion polls conducted from 1966 to 2004 found that as many as 80 percent of Americans do not believe that Oswald acted alone and have suspected that there was a plot or cover-up.[27]

The assassination is still the subject of widespread debate and has spawned numerous conspiracy theories and alternative scenarios.

Burial

On March 14, 1967, Kennedy's body was moved to a permanent burial place and memorial at Arlington National Cemetery. He is buried with his wife and their deceased minor children, and his brother, the late Senator Robert Kennedy is also buried nearby. His grave is lit with an "Eternal Flame." In the film The Fog of War, then Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara claims that he picked the location in the cemeteryâa location which Jackie agreed was suitable. Kennedy and William Howard Taft are the only two U.S. Presidents buried at Arlington.

Legacy

Television became the primary source by which people were kept informed of events surrounding John F. Kennedy's assassination. Newspapers were kept as souvenirs rather than sources of updated information. All three major U.S. television networks suspended their regular schedules and switched to all-news coverage from November 22 through November 25, 1963. Kennedy's state funeral procession and the murder of Lee Harvey Oswald were all broadcast live in America and in other places around the world. The state funeral was the first of three in a span of 12 months: The other two were for General Douglas MacArthur and President Herbert Hoover.

The assassination had an effect on many people, not only in the U.S. but also among the world population. Many vividly remember where they were when first learning of the news that Kennedy was assassinated, like with the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941 before it and the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and Pentagon on September 11, 2001 after it. U.S. ambassador to the U.N. Adlai Stevenson said of the assassination, "all of us... will bear the grief of his death until the day of ours."

Coupled with the murder of his own brother, Senator Robert F. Kennedy, and that of Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., the five tumultuous years from 1963 to 1968 signaled a growing disillusionment within the well of hope for political and social change which so defined the lives of those who lived through the 1960s. Ultimately, the death of President Kennedy and the ensuing confusion surrounding the facts of his assassination are of political and historical importance insofar as they marked a decline in the faith of the American people in the political establishment â a point made by commentators from Gore Vidal to Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr.. Kennedy's continuation of Presidents Truman's and Eisenhower's policies of giving economic and military aid to the Vietnam War preceded President Johnson's escalation of the conflict. This contributed to a decade of national difficulties and disappointment on the political landscape.

Many of Kennedy's speeches (especially his inaugural address) are considered iconic; and despite his relatively short term in office and lack of major legislative changes during his term, Americans regularly vote him as one of the best presidents, in the same league as Abraham Lincoln, George Washington and Franklin D. Roosevelt.[28]

Some excerpts of Kennedy's inaugural address are engraved on a plaque at his grave at Arlington.

He was posthumously awarded the Pacem in Terris Award. It was named after a 1963 encyclical letter by Pope John XXIII that calls upon all people of goodwill to secure peace among all nations. Pacem in Terris is Latin for "Peace on Earth."

Notes

- â Bryan Wendell, Remembering John F. Kennedy, the first president to have been a Boy Scout Scouting Magazine. November 22, 2013. Retrieved April 30, 2023.

- â John F. Kennedy, Why England Slept (Ishi Press, 2016 (original 1940), ISBN 978-4871877671).

- â Duane T. Hove, American Warriors: Five Presidents in the Pacific Theater of WWII (Burd Street Press, 2003, ISBN 1572493070).

- â Biography and Autobiography Pulitzer.org. Retrieved April 30, 2023.

- â Thomas C. Reeves, A Question of Character: A Life of John F. Kennedy (New York: Free Press, 1991, ISBN 9780029259658), 140.

- â President Kennedyâs Health Secrets PBS Online News Hour, with Ray Suarez, November 18, 2002. Retrieved April 30, 2023.

- â Michael O'Brien, John F. Kennedy A Biography (New York: Thomas Dunne Books/St. Martin's Press, 2005, ISBN 9780312281298), 274-279, 394-399.

- â Address to the Greater Houston Ministerial Association aAmerican Rhetoric. Retrieved April 30, 2023.

- â Edmund F. Kalina, Courthouse over White House, Chicago and the Presidential Election of 1960 (Orlando: University of Central Florida Press, 1988, ISBN 9780813008646).

- â President John F. Kennedy's Inaugural Address (1961) National Archives. Retrieved April 30, 2023.

- â 11.0 11.1 Arthur Meier Schlesinger, Robert Kennedy and His Times (Mariner Books, 2002, ISBN 9780618219285)

- â Walter LaFeber, America, Russia, and the Cold War, 1945-1966 (New York: Wiley, 1967), 233.

- â Press Version of How Diem and Nhu Died George Washington University. Retrieved April 30, 2023.

- â Joseph Ellis, "Making Vietnam History," review of: David Kaiser, American Tragedy: Kennedy, Johnson, and the Origins of the Vietnam War (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000) in Reviews in American History 28 (4) (2000): 625â629.

- â John F. Kennedy, Commencement Address, American University, June 10, 1963 John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. Retrieved April 30, 2023.

- â Jean Edward Smith, The Defense of Berlin (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Press, 1963).

- â 1963: Warm welcome for JFK in Ireland BBC News. Retrieved April 30, 2023.

- â Hanna Batatu, The Old Social Classes and the Revolutionary Movements of Iraq (Saqi Books, 2004, ISBN 0863565204).

- â Peter Sluglett and Marion Farouk-Sluglett, Iraq Since 1958: From Revolution to Dictatorship (London: I.B. Taurus, 2001, ISBN 1860646220).

- â Martin Luther King, Jr. Biographical Sketch Louisiana State University Library. Retrieved April 30, 2023.

- â John F. Kennedy, Civil Rights Address delivered June 11, 1963 American Rhetoric. Retrieved April 30, 2023.

- â Jennifer Ludden, Q&A: Sen. Kennedy on Immigration, Then & Now NPR, May 9, 2006. Retrieved April 30, 2023.

- â From Press Office: Senator John F. Kennedy, Immigration and Naturalization Laws, Hyannis Inn Motel, Hyannis, MA Retrieved April 30, 2023.

- â Address to Joint Session of Congress, May 25, 1961 John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. Retrieved April 30, 2023.

- â John F. Kennedy, "We choose to go to the Moon" Rice University, September 12, 1962. Retrieved April 30, 2023.

- â JFK Assassination Records National Archives. Retrieved April 30, 2023.

- â Gary Langer, John F. Kennedyâs Assassination Leaves a Legacy of Suspicion ABC News, November 16, 2003. Retrieved April 30, 2023.

- â American Experience: the Presidents John F. Kennedy, 35th president, American Experience: JFK PBSg, November 12, 2013. Retrieved April 30, 2023.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Batatu, Hanna. The Old Social Classes and The Revolutionary Movement In Iraq. London: Saqi Books, 2004. ISBN 9780863565205

- Brauer, Carl M. John F. Kennedy and the Second Reconstruction. New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 1977. ISBN 9780231038621

- Bugliosi, Vincent. Reclaiming History: The Assassination of President John F. Kennedy. New York, NY: W. W. Norton, 1st edition, 2007. ISBN 0393045250

- Burner, David. John F. Kennedy and a New Generation. The Library of American biography. Boston, MA: Little, Brown, 1988. ISBN 9780316117241

- Collier, Peter, and David Horowitz. The Kennedys An American Drama. New York, NY: Summit Books, 1984. ISBN 9780671447939

- Cottrell, John. Assassination! The World Stood Still. Four square book. London: New English Library, 1964. ASIN B001SS1SP4

- Dallek, Robert. An Unfinished Life: John F. Kennedy, 1917-1963. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company, 2003. ISBN 0316172383

- Freedman, Lawrence. Kennedy's Wars Berlin, Cuba, Laos, and Vietnam. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2000. ISBN 9780195134537

- Fursenko, Aleksandr, and Timothy J. Naftali. One Hell of a Gamble Khrushchev, Castro, and Kennedy, 1958-1964. New York, NY: Norton, 1997. ISBN 9780393040708

- Harper, Paul, and Joann P. Krieg (eds.). John F. Kennedy, the Promise Revisited. New York, NY: Greenwood Press, 1988. ISBN 9780313262012

- Harris, Seymour Edwin. The Economics of the Political Parties, with Special Attention to Presidents Eisenhower and Kennedy. New York, NY: Macmillan, 1962. ASIN B0000CLIHQ

- Hersh, Seymour M. The Dark Side of Camelot. Boston, MA: Little, Brown, 1997. ISBN 9780316359559

- Hove, Duane T. American Warriors: Five Presidents in the Pacific Theater of WWII. Burd Street Press, 2003. ISBN 1572493070

- Kaiser, David. American Tragedy: Kennedy, Johnson, and the Origins of the Vietnam War. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press/Belknap Press, 2002. ISBN 0674006720

- Kalina, Edmund F. Courthouse over White House, Chicago and the Presidential Election of 1960. Orlando, FL: University of Central Florida Press, 1988. ISBN 9780813008646

- Kennedy, John F. Why England Slept. Ishi Press, 2016 (original 1940). ISBN 978-4871877671

- LaFeber, Walter. America, Russia, and the Cold War, 1945-1966. New York, NY: Wiley, 1968. ASIN B000GS7UPY

- O'Brien, Michael. John F. Kennedy A Biography. New York, NY: Thomas Dunne Books/St. Martin's Press, 2005. ISBN 9780312281298

- Parmet, Herbert S. Jack The Struggles of John F. Kennedy. New York, NY: Dial Press, 1980. ISBN 9780803744523

- Parmet, Herbert S. JFK, the Presidency of John F. Kennedy. New York, NY: Dial Press, 1983. ISBN 9780385274197

- Reeves, Richard. President Kennedy Profile of Power. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, 1993. ISBN 9780671648794

- Reeves, Thomas C. A Question of Character A Life of John F. Kennedy. New York, NY: Free Press, 1991. ISBN 9780029259658

- Schlesinger, Arthur M. A Thousand Days; John F. Kennedy in the White House. Mariner Books, 2002. ISBN 9780618219278

- Schlesinger, Arthur Meier. Robert Kennedy and His Times. Mariner Books, 2002. ISBN 9780618219285

- Sluglett, Peter, and Marion Farouk-Sluglett. Iraq Since 1958: From Revolution to Dictatorship. London: I.B. Taurus, 2001. ISBN 1860646220

- Smith, Jean Edward. The Defense of Berlin. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Press, 1963. ASIN B0006D6JJW

- Smith, Jean Edward. The Wall As Watershed. Arlington, VA: Institute for Defense Analyses, Economic and Political Studies Division, 1966. ASIN B0007EGVMU

- United States House of Representatives. The Final Assassinations Report Report. New York, NY: Bantam Books, 1979. ISBN 9780553135008

- Walsh, Kenneth T. Air Force One A History of the Presidents and Their Planes. New York, NY: Hyperion, 2003. ISBN 9781401300043

External links

All links retrieved January 30, 2025.

- American President John F. Kennedy (1917â1963) Miller Center (UVA)

- Video, Audio, Text of John F. Kennedy's Inaugural Address American Rhetoric

- John F. Kennedy Library

- Inaugural Address of John F. Kennedy The Avalon Project

- New video footage released of JFK's last moments BBC News, February 20, 2007.

| |||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.