Decolonization

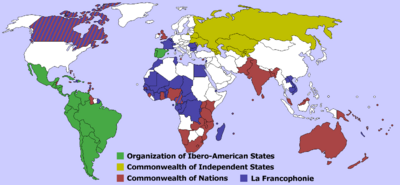

Decolonization refers to the undoing of colonialism, the establishment of governance or authority through the creation of settlements by another country or jurisdiction. The term generally refers to the achievement of independence by the various Western colonies and protectorates in Asia and [Africa]] following World War II. This conforms with an intellectual movement known as Post-Colonialism. A particularly active period of decolonization occurred between 1945 to 1960, beginning with the independence of Pakistan and the Republic of India from Great Britain in 1947 and the First Indochina War. Some national liberation movements were established before the war, but most did not achieve their aims until after it. Decolonization can be achieved by attaining independence, integrating with the administering power or another state, or establishing a "free association" status. The United Nations has stated that in the process of decolonization there is no alternative to the principle of self-determination.

Partly, decolonization was overseen by the United Nations, with UN membership as the prize each newly independent nation cherished as a sign of membership in the community of nations. The United Nations Trusteeship Council was suspended in 1994, after Palau, the last remaining United Nations trust territory, achieved independence. From 1945 and the end of the twentieth century, the number of sovereign nation-states mushroomed from 50 to 192 and few stopped to ask if this was the right direction for human political organization to be moving. Decolonization may involve peaceful negotiation, non-violent protest or violent revolt and armed struggle. Or, one faction pursues one strategy while another pursues the opposite. Some argue because of neocolonialism many former colonies are not truly free but remain dependent on the world's leading nations. No one of principle wants to deny people their freedom, or perpetuate oppression, injustice and inequality. However, while many celebrate decolonization in the name of freedom and realization of the basic human rights of self-determination, others question whether equality, justice, peace, the end of poverty, exploitation and the dependency of some on others can be achieved as long as nation-states promote and protect their own interests, interests that are not always at the expense of others' but which often are. As freedom spreads around the world, as more people gain the liberty to determine their own futures, some people hope that a new world order might develop, with the nation state receding in significance. Instead, global institutions would consider the needs of the planet and of all its inhabitants.

Methods and stages

Decolonization is a political process, frequently involving violence. In extreme circumstances, there is a war of independence, sometimes following a revolution. More often, there is a dynamic cycle where negotiations fail, minor disturbances ensue resulting in suppression by the police and military forces, escalating into more violent revolts that lead to further negotiations until independence is granted. In rare cases, the actions of the native population are characterized by non-violence, India being an example of this, and the violence comes as active suppression from the occupying forces or as political opposition from forces representing minority local communities who feel threatened by the prospect of independence. For example, there was a war of independence in French Indochina, while in some countries in French West Africa (excluding the Maghreb countries) decolonization resulted from a combination of insurrection and negotiation. The process is only complete when the de facto government of the newly independent country is recognized as the de jure sovereign state by the community of nations.

Independence is often difficult to achieve without the encouragement and practical support from one or more external parties. The motives for giving such aid are varied: nations of the same ethnic and/or religious stock may sympathize with oppressed groups, or a strong nation may attempt to destabilize a colony as a tactical move to weaken a rival or enemy colonizing power or to create space for its own sphere of influence; examples of this include British support of the Haitian Revolution against France, and the Monroe Doctrine of 1823, in which the United States warned the European powers not to interfere in the affairs of the newly independent states of the Western Hemisphere.

As world opinion became more pro-emancipation following World War I, there was an institutionalized collective effort to advance the cause of emancipation through the League of Nations. Under Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations, a number of mandates were created. The expressed intention was to prepare these countries for self-government, but the reality was merely a redistribution of control over the former colonies of the defeated powers, mainly Germany and the Ottoman Empire. This reassignment work continued through the United Nations, with a similar system of trust territories created to adjust control over both former colonies and mandated territories administered by the nations defeated in World War II, including Japan. In 1960, the UN General Assembly adopted the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples. This stated that all people have a right to self-determination and proclaimed that colonialism should be speedily and unconditionally brought to an end. When the United Nations was founded, some wanted to place oversight of the decolonization process of all non-self governing territories under the oversight of the Trusteeship Council. Not only was this resisted by the colonial powers, but the UN Charter did not explicitly affirm self-determination as a right; instead, Articles 1, 55 and 56 express "respect for the principle of self-determination." Although the Trusteeship Council was only responsible for supervising progress towards independence of Trust territories, the colonial powers were required to report to the UN Secretary-General on the "educational, social and economic conditions" in their territories, a rather vague obligation that did not specify progress towards independence.[1]

In referendums, some colonized populations have chosen to retain their colonial status, such as Gibraltar and French Guiana. On the other hand, colonial powers have sometimes promoted decolonization in order to shed the financial, military and other burdens that tend to grow in those colonies where the colonial regimes have become more benign.

Empires have expanded and contracted throughout history but, in several respects, the modern phenomenon of decolonization has produced different outcomes. Now, when states surrender both the de facto rule of their colonies and their de jure claims to such rule, the ex-colonies are generally not absorbed by other powers. Further, the former colonial powers have, in most cases, not only continued existing, but have also maintained their status as Powers, retaining strong economic and cultural ties with their former colonies. Through these ties, former colonial powers have ironically maintained a significant proportion of the previous benefits of their empires, but with smaller costs—thus, despite frequent resistance to demands for decolonization, the outcomes have satisfied the colonizers' self-interests.

Decolonization is rarely achieved through a single historical act, but rather progresses through one or more stages of emancipation, each of which can be offered or fought for: these can include the introduction of elected representatives (advisory or voting; minority or majority or even exclusive), degrees of autonomy or self-rule. Thus, the final phase of decolonization may in fact concern little more than handing over responsibility for foreign relations and security, and soliciting de jure recognition for the new sovereignty. But, even following the recognition of statehood, a degree of continuity can be maintained through bilateral treaties between now equal governments involving practicalities such as military training, mutual protection pacts, or even a garrison and/or military bases.

There is some debate over whether or not the United States, Canada and Latin America can be considered decolonized, as it was the colonist and their descendants who revolted and declared their independence instead of the indigenous peoples, as is usually the case. Scholars such as Elizabeth Cook-Lynn (Dakota)[2] and Devon Mihesuah (Choctaw)[3] have argued that portions of the United States still are in need of decolonization.

Decolonization in a broad sense

Stretching the notion further, internal decolonization can occur within a sovereign state. Thus, the expansive United States created territories, destined to colonize conquered lands bordering the existing states, and once their development proved successful (often involving new geographical splits) allowed them to petition statehood within the federation, granting not external independence but internal equality as 'sovereign' constituent members of the federal Union. France internalized several overseas possessions as Départements d'outre-mer.

Even in a state which legally does not colonize any of its 'integral' parts, real inequality often causes the politically dominant component - often the largest and/or most populous part (such as Russia within the formally federal USSR as earlier in the czar's empire), or the historical conqueror (such as Austria, the homelands of the ruling Habsburg dynasty, within an empire of mainly Slavonic 'minorities' from Silesia to the shifting (Ottoman border) - to be perceived, at least subjectively, as a colonizer in all but name; hence, the dismemberment of such a 'prison of peoples' is perceived as decolonization de facto.

To complicate matters even further, this may coincide with another element. Thus, the three Baltic republics - Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania - argue that they, in contrast with other constituent SSRs, could not have been granted independence at the dismemberment of the Soviet Union because they never joined, but were militarily annexed by Stalin, and thus had been illegally colonized, including massive deportations of their nationals and uninvited immigration of ethnic Russians and other soviet nationalities. Even in other post-Soviet states which had formally acceded, most ethnic Russians were so much identified with the Soviet 'colonization,' they felt unwelcome and migrated back to Russia.

When the UN was established, roughly one-third of the world was under some type of colonial rule. At the start of the twenty-first century, less than two million people live under such governance.

Decolonization before 1918

One of the most significant, and early, events in the history of pre-1918 decolonization was the rebellion of the 13 American colonies of the British Empire against British rule. This established the principles that people have the right to rebel against what they perceive to be unjust rule and governance in which they have no participation. Britain recognized the independence of the United States in 1783. Determined not to totally lose other settler colonies (colonies where British people settled in large number, claiming the territory for the British crown regardless of the rights of indigenous people) and developed a system to grant self-rule within the Empire to such colonies as Canada, Australia and New Zealand, which became Dominions in 1867, 1901 and 1907 respectively. At the same time, Britain was much more reluctant to grant non-settler colonies very much participation in governance and after 1919 through the League of Nations mandate system expanded its empire by acquiring Iraq, British Mandate of Palestine and Jordan, territories that the great powers considered required oversight (later, the term Trusteeship was used by the UN]] until they were ready for self-governance.

Decolonization also took place within the Ottoman imperial space, beginning with Greece whose independence was recognized in 1831. The great powers, who had much to say about the "Turkish yoke" and the "Turkish peril" supported Greece but were well aware of the ambiguity of their position. They also possessed Empires and theirs were no less oppressive than that of the Ottomans. Austria-Hungary was especially reluctant to see the collapse of the Ottoman, thinking that the future of their own system, governed by a more or less absolute ruler, might be bound up with that of a similar polity. However, inspired by the new ideal of nationalism stimulated by the French and American revolutions, provinces in the Balkans revived memories of their medieval kingdoms and began freedom struggles. One by one, the Ottoman Empire lost its European possessions until by the start of World War I none were left. After the war, the rest of its empire was distributed among Britain (Iraq, Jordan, Palestine), France (Syria, Lebanon) and Italy (Libya).

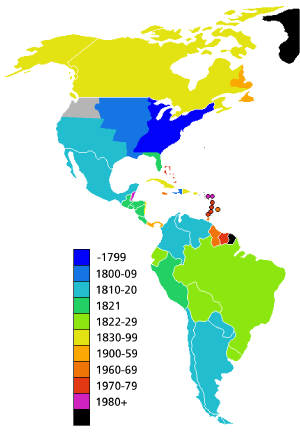

Also spurred on by events further North, the American colonies in the South under mainly Spanish rule with Brazil under Portugal began a series of independence movements. The second county in the region to gain its freedom was Haiti, where a slave uprising started in 1791. The wars for the independence of South America began in 1806 to and continued until 1826.

- Venezuela declared independence from July 5, 1811. It was ten years before Simon Bolivar secured freedom.

- Argentina declared independence from July 9, 1816.

- Bolivia gained independence on August 6, 1822 after a war led by Simon Bolivar, after whom the new republic named itself.

- Chile declared independence September 8, 1811.

- Ecuador gained independence May 34, 1822.

- Colombia ended its independence war on July 20, 1819.

- Brazil became independent September 7, 1822.

- Paraguay became independent on May 15, 1811.

- Peru became independence July 28, 1821.

- Uruguay August 25, 1825.

Most Central American countries gained independence in 1821, namely Costa Rica, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua and Panama. Belize, a British colony, did not become independent until 1981. Guyana, also British, became independent in 1966 and Surinam, a Netherlands colony in 1975.

Decolonization after 1918

Western European colonial powers

The New Imperialism period, with the Scramble for Africa and the Opium Wars, marked the zenith of European colonization. It also marked the acceleration of the trends that would end it. The extraordinary material demands of the conflict had spread economic change across the world (notably inflation), and the associated social pressures of "war imperialism" created both peasant unrest and a burgeoning middle class.

Economic growth created stakeholders with their own demands, while racial issues meant these people clearly stood apart from the colonial middle-class and had to form their own group. The start of mass nationalism, as a concept and practice, would fatally undermine the ideologies of imperialism.

There were, naturally, other factors, from agrarian change (and disaster – French Indochina), changes or developments in religion (Buddhism in Burma, Islam in the Dutch East Indies, marginally people like John Chilembwe in Nyasaland), and the impact of the depression of the 1930s.

The Great Depression, despite the concentration of its impact on the industrialized world, was also exceptionally damaging in the rural colonies. Agricultural prices fell much harder and faster than those of industrial goods. From around 1925 until World War II, the colonies suffered. The colonial powers concentrated on domestic issues, protectionism and tariffs, disregarding the damage done to international trade flows. The colonies, almost all primary "cash crop" producers, lost the majority of their export income and were forced away from the "open" complementary colonial economies to "closed" systems. While some areas returned to subsistence farming (Malaysia) others diversified (India, West Africa), and some began to industrialize. These economies would not fit the colonial strait-jacket when efforts were made to renew the links. Further, the European-owned and -run plantations proved more vulnerable to extended deflation than native capitalists, reducing the dominance of "white" farmers in colonial economies and making the European governments and investors of the 1930s co-opt indigenous elites — despite the implications for the future.

The efforts at colonial reform also hastened their end — notably the move from non-interventionist collaborative systems towards directed, disruptive, direct management to drive economic change. The creation of genuine bureaucratic government boosted the formation of indigenous bourgeoisie. This was especially true in the British Empire, which seemed less capable (or less ruthless) in controlling political nationalism. Driven by pragmatic demands of budgets and manpower the British made deals with the nationalist elites. They dealt with the white Dominions, retained strategic resources at the cost of reducing direct control in Egypt, and made numerous reforms in the Raj, culminating in the Government of India Act (1935).

Africa was a very different case from Asia between the wars. Tropical Africa was not fully drawn into the colonial system before the end of the 19th century, excluding only the complexities of the Union of South Africa (busily introducing racial segregation from 1924 and thus catalyzing the anti-colonial political growth of half the continent) and the Empire of Ethiopia. Colonial controls ranged between extremes. Economic growth was often curtailed. There were no indigenous nationalist groups with widespread popular support before 1939.

The United States

At end of the Spanish-American War, at the end of the nineteenth century, the United States of America held several colonial territories seized from Spain, among them the Philippines and Puerto Rico. Although the United States had initially embarked upon a policy of colonization of these territories (and had fought to suppress local "insurgencies" there, such as in the Philippine-American War), by the 1930s, the U.S. policy for the Philippines had changed toward the direction of eventual self-government. Following the invasion and occupation of the Philippines by Japan during World War II, the Philippines gained independence peacefully from the United States in 1946.

However, other U.S. possessions, such as Puerto Rico, did not gain full independence. Puerto Ricans have held U.S. citizenship since 1917, but do not pay federal income tax. In 2000, a U.S. District judge ruled that Puerto Ricans can vote in U.S. Presidential elections for the first time. Puerto Rico achieved self-government in 1952 and became a commonwealth in association with the United States. Puerto Rico was taken off the UN list of non-sovereign territories in 1953 through resolution 748. In 1967, 1993 and 1998, Puerto Rican voters rejected proposals to grant the territory U.S. statehood or independence. Nevertheless, the island's political status remains a hot topic of debate.

Japan

As the only Asian nation to become a colonial power during the modern era, Japan had gained several substantial colonial concessions in east Asia such as Taiwan and Korea. Pursuing a colonial policy comparable to those of European powers, Japan settled significant populations of ethnic Japanese in its colonies while simultaneously suppressing indigenous ethnic populations by enforcing the learning and use of the Japanese language in schools. Other methods such as public interaction, and attempts to eradicate the use of Korean and Taiwanese (Min Nan) among the indigenous peoples, were seen to be used. Japan also set up the Imperial university in Korea (Keijo Imperial University) and Taiwan (Taihoku University) to compel education.

World War II gave Japan occasion to conquer vast swaths of Asia, sweeping into China and seizing the Western colonies of Vietnam, Hong Kong, the Philippines, Burma, Malaya, Timor and Indonesia among others, albeit only for the duration of the war. Following its surrender to the Allies in 1945, Japan was deprived of all its colonies. Japan further claims that the southern Kuril Islands are a small portion of its own national territory, colonized by the Soviet Union.

French Decolonization

After World War I, the colonized people were frustrated at France's failure to recognize the effort provided by the French colonies (resources, but more importantly colonial troops - the famous tirailleurs). Although in Paris the Great Mosque of Paris was constructed as recognition of these efforts, the French state had no intention to allow self-rule, let alone independence to the colonized people. Thus, nationalism in the colonies became stronger in between the two wars, leading to Abd el-Krim's Rif War (1921-1925) in Morocco and to the creation of Messali Hadj's Star of North Africa in Algeria in 1925. However, these movements would gain full potential only after World War II. The October 27, 1946 Constitution creating the Fourth Republic substituted the French Union to the colonial empire. On the night of March 29, 1947, a nationalist uprising in Madagascar led the French government led by Paul Ramadier (Socialist) to violent repression: one year of bitter fighting, in which 90,000 to 100,000 Malagasy died. On May 8, 1945, the Sétif massacre took place in Algeria.

In 1946, the states of French Indochina withdrew from the Union, leading to the Indochina War (1946-54) against Ho Chi Minh, who had been a co-founder of the French Communist Party in 1920 and had founded the Vietminh in 1941. In 1956, Morocco and Tunisia gained their independence, while the Algerian War was raging (1954-1962). With Charles de Gaulle's return to power in 1958 amidst turmoil and threats of a right-wing coup d'Etat to protect "French Algeria," the decolonization was completed with the independence of Sub-Saharan Africa's colonies in 1960 and the March 19, 1962 Evian Accords, which put an end to the Algerian war. The OAS movement unsuccessfully tried to block the accords with a series of bombings, including an attempted assassination against Charles de Gaulle.

To this day, the Algerian war — officially called until the 1990s a "public order operation" — remains a trauma for both France and Algeria. Philosopher Paul Ricoeur has spoken of the necessity of a "decolonization of memory," starting with the recognition of the 1961 Paris massacre during the Algerian war and the recognition of the decisive role of African and especially North African immigrant manpower in the Trente Glorieuses post-World War II economic growth period. In the 1960s, due to economic needs for post-war reconstruction and rapid economic growth, French employers actively sought to recruit manpower from the colonies, explaining today's multiethnic population.

The Soviet Union and anti-colonialism

The Soviet Union sought to effect the abolishment of colonial governance by Western countries, either by direct subversion of Western-leaning or -controlled governments or indirectly by influence of political leadership and support. Many of the revolutions of this time period were inspired or influenced in this way. The conflicts in Vietnam, Nicaragua, Congo, and Sudan, among others, have been characterized as such.

Most Soviet leaders expressed the Marxist-Leninist view that imperialism was the height of capitalism, and generated a class-stratified society. It followed, then, that Soviet leadership would encourage independence movements in colonized territories, especially as the Cold War progressed. Because so many of these wars of independence expanded into general Cold War conflicts, the United States also supported several such independence movements in opposition to Soviet interests.

During the Vietnam War, Communist countries supported anti-colonialist movements in various countries still under colonial administration through propaganda, developmental and economic assistance, and in some cases military aid. Notably among these were the support of armed rebel movements by Cuba in Angola, and the Soviet Union (as well as the People's Republic of China) in Vietnam.

It is noteworthy that while England, Spain, Portugal, France, and the Netherlands took colonies overseas, the Russian Empire expanded via land across Asia. The Soviet Union did not make any moves to return this land.

The Emergence of the Third World (1945- )

The term "Third World" was coined by French demographer Alfred Sauvy in 1952, on the model of the Third Estate, which, according to the Abbé Sieyès, represented everything, but was nothing: "…because at the end this ignored, exploited, scorned Third World like the Third Estate, wants to become something too" (Sauvy). The emergence of this new political entity, in the frame of the Cold War, was complex and painful. Several tentatives were made to organize newly independent states in order to oppose a common front towards both the US's and the USSR's influence on them, with the consequences of the Sino-Soviet split already at works. Thus, the Non-Aligned Movement constituted itself, around the main figures of Nehru, the leader of India, The Indonesian prime minister, Tito the Communist leader of Yugoslavia, and Nasser, head of Egypt who successfully opposed the French and British imperial powers during the 1956 Suez crisis. After the 1954 Geneva Conference which put an end to the French war against Ho Chi Minh in Vietnam, the 1955 Bandung Conference gathered Nasser, Nehru, Tito, Sukarno, the leader of Indonesia, and Zhou Enlai, Premier of the People's Republic of China. In 1960, the UN General Assembly voted the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples. The next year, the Non-Aligned Movement was officially created in Belgrade (1961), and was followed in 1964 by the creation of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) which tried to promote a New International Economic Order (NIEO). The NIEO was opposed to the 1944 Bretton Woods system, which had benefited the leading states which had created it, and remained in force until after the 1973 oil crisis. The main tenets of the NIEO were:

- Developing countries must be entitled to regulate and control the activities of multinational corporations operating within their territory.

- They must be free to nationalize or expropriate foreign property on conditions favorable to them.

- They must be free to set up voluntary association of primary commodities producers similar to the OPEC (Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, created on September 17, 1960 to protest pressure by major oil companies (mostly owned by U.S., British, and Dutch nationals) to reduce oil prices and payments to producers.); all other States must recognize this right and refrain from taking economic, military, or political measures calculated to restrict it.

- International trade should be based on the need to ensure stable, equitable, and remunerative prices for raw materials, generalized non-reciprocal and non-discriminatory tariff preferences, as well as transfer of technology] to developing countries; and should provide economic and technical assistance without any strings attached.

The UNCTAD however wasn't very effective in implementing this New International Economic Order (NIEO), and social and economic inequalities between industrialized countries and the Third World kept on growing through-out the 1960s until the twenty-first century. The 1973 oil crisis which followed the Yom Kippur War (October 1973) was triggered by the OPEC which decided an embargo against the US and Western countries, causing a fourfold increase in the price of oil, which lasted five months, starting on October 17, 1973, and ending on March 18, 1974. OPEC nations then agreed, on January 7 1975, to raise crude oil prices by ten percent. At that time, OPEC nations—including many who had recently nationalized their oil industries—joined the call for a New International Economic Order to be initiated by coalitions of primary producers. Concluding the First OPEC Summit in Algiers they called for stable and just commodity prices, an international food and agriculture program, technology transfer from North to South, and the democratization of the economic system. But industrialized countries quickly began to look for substitutes to OPEC petroleum, with the oil companies investing the majority of their research capital in the US and European countries or others, politically secure countries. The OPEC lost more and more influence on the world prices of oil.

The second oil crisis occurred in the wake of the 1979 Iranian Revolution. Then, the 1982 Latin American debt crisis exploded in Mexico first, then Argentina and Brazil, who were unable to pay back their debts, jeopardizing the existence of the international economic system.

The 1990s were characterized by the prevalence of the Washington [4] neoliberal policies, "structural adjustment" and "shock therapies" for the former Communist states, to transform command economies into self-sustaining trade-based economies capable of participating in the free-trade world market.

Assassinated anticolonialist leaders

A non-exhaustive list of assassinated leaders includes:

- Ruben Um Nyobé, leader of the Union of the Peoples of Cameroon (UPC), killed by the French army on September 13, 1958

- Barthélemy Boganda, leader of a nationalist Central African Republic movement, who died in a plane-crash on March 29, 1959, eight days before the last elections of the colonial era.

- Félix-Roland Moumié, successor to Ruben Um Nyobe at the head of the UPC, assassinated in Geneva in 1960 by the SDECE (French secret services).[5]

- Patrice Lumumba, the first Prime minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, was assassinated on January 17, 1961.

- Burundi nationalist Louis Rwagasore was assassinated on October 13, 1961, while Pierre Ngendandumwe, Burundi's first Hutu]prime minister, was also murdered on January 15, 1965.

- Sylvanus Olympio, the first president of Togo, was assassinated on January 13, 1963. He would be replaced by Gnassingbé Eyadéma, who ruled Togo for nearly 40 years; he died in 2005 and was succeeded by his son Faure Gnassingbé.

- Mehdi Ben Barka, the leader of the Moroccan National Union of Popular Forces (UNPF) and of the Tricontinental Conference, which was supposed to prepare in 1966 in Havana its first meeting gathering national liberation movements from all continents — related to the Non-Aligned Movement, but the Tricontinental Conference gathered liberation movements while the Non-Aligned were for the most part states — was "disappeared" in Paris in 1965.

- Nigerian leader Ahmadu Bello was assassinated in January 1966.

- Eduardo Mondlane, the leader of FRELIMO and the father of Mozambican independence, was assassinated in 1969, allegedly by Aginter Press, the Portuguese branch of Gladio, NATO's paramilitary organization during the Cold War.

- Pan-Africanist Tom Mboya was killed on July 5, 1969.

- Abeid Karume, first president of Zanzibar, was assassinated in April 1972.

- Amílcar Cabral was murdered on January 20, 1973.

- Outel Bono, Chadian opponent of François Tombalbaye, was assassinated on August 26, 1973, making yet another example of the existence of the Françafrique, designing by this term post-independent neocolonial ties between France and its former colonies.

- Herbert Chitepo, leader of the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU), was assassinated on March 18, 1975.

- Óscar Romero, prelate archbishop of San Salvador and proponent of liberation theology, was assassinated on March 24, 1980

- Dulcie September, leader of the African National Congress (ANC), who was investigating an arms trade between France and South Africa, was murdered in Paris on March 29, 1988, a few years before the end of the apartheid regime.

Many of these assassinations are still unsolved cases as of 2007, but foreign power interference is undeniable in many of these cases — although others were for internal matters. To take only one case, the investigation concerning Mehdi Ben Barka is continuing to this day, and both France and the United States have refused to declassify files they acknowledge having in their possession[6] The Phoenix Program, a CIA program of assassination during the Vietnam War, should also be named.

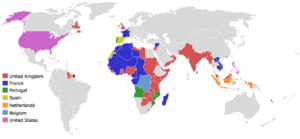

Post-colonial organizations

Due to a common history and culture, former colonial powers created institutions which more loosely associated their former colonies. Membership is voluntary, and in some cases can be revoked if a member state loses some objective criteria (usually a requirement for democratic governance). The organizations serve cultural, economic, and political purposes between the associated countries, although no such organization has become politically prominent as an entity in its own right.

| Former Colonial Power | Organization | Founded |

|---|---|---|

| Britain | Commonwealth of Nations | 1931 |

| Commonwealth Realms | 1931 | |

| Associated states | 1967 | |

| France | French Union | 1946 |

| French Community | 1958 | |

| Francophonie | 1970 | |

| Spain & Portugal | Latin Union | 1954 |

| Organization of Ibero-American States | 1991 | |

| Community of Portuguese Language Countries | 1996 | |

| United States | Commonwealths | 1934 |

| Freely Associated States | 1982 | |

| European Union | ACP countries | 1975 |

Differing perspectives

Decolonization generates debate and controversy. The end goal tends to be universally regarded as good, but there has been much debate over the best way to grant full independence.

Decolonization and political instability

Some say the post–World War II decolonization movement was too rushed, especially in Africa, and resulted in the creation of unstable regimes in the newly independent countries. Thus causing war between and within the new independent nation-states.

Others argue that this instability is largely the result of problems from the colonial period, including arbitrary nation-state borders, lack of training of local populations and disproportional economy. However by the twentieth century most colonial powers were slowly being forced by the moral beliefs of population to increase the welfare of their colonial subjects.

Some would argue a form of colonization still exists in the form of economic colonialism carried out by U.S owned corporations operating across the globe.

Economic effects

Effects on the colonizers

John Kenneth Galbraith (who served as US Ambassador in India) argues that the post-World War II decolonization was brought about for economic reasons. In A Journey Through Economic Time, he writes, "The engine of economic well-being was now within and between the advanced industrial countries. Domestic economic growth — as now measured and much discussed — came to be seen as far more important than the erstwhile colonial trade…. The economic effect in the United States from the granting of independence to the Philippines was unnoticeable, partly due to the Bell Trade Act, which allowed American monopoly in the economy of the Philippines. The departure of India and Pakistan made small economic difference in Britain. Dutch economists calculated that the economic effect from the loss of the great Dutch empire in Indonesia was compensated for by a couple of years or so of domestic post-war economic growth. The end of the colonial era is celebrated in the history books as a triumph of national aspiration in the former colonies and of benign good sense on the part of the colonial powers. Lurking beneath, as so often happens, was a strong current of economic interest — or in this case, disinterest."[7] Galbraith takes the view that the main drive behind colonial expansion was economic - colonies were a "rich source of raw materials" and "a significant market for elementary manufactured goods." Once "domestic economic growth" became a priority as opposed to "colonial trade," the colonial world became "marginalized," so "it was to the advantage of all to let it go." [8]Galbraith says that combined with the cost of waging war to retain colonies, the shift in economical priority meant that the "practical course was to let the brothers go in peace." It was thus somewhat incidental that "erstwhile possessions" also had "a natural right to their own identity" and "to govern themselves." [9]

Part of the reason for the lack of economic impact felt by the colonizer upon the release of the colonized was that costs and benefits were not eliminated, but shifted. The colonizer no longer had the burden of obligation, financial or otherwise, for their colony. The colonizer continued to be able to obtain cheap goods and labor as well as economic benefits (see Suez Canal Crisis) from the former colonies. Financial, political and military pressure could still be used to achieve goals desired by the colonizer. The most obvious difference is the ability of the colonizer to disclaim responsibility for the colonized.

Effects on the former colonies

Settled populations

Decolonization is not an easy adjustment in colonies where a large population of settlers live, particularly if they have been there for several generations. This population, in general, may have to be repatriated, often losing considerable property. For instance, the decolonization of Algeria by France was particularly uneasy due to the large European and Sephardic Jewish population (see also pied noir), which largely evacuated to France when Algeria became independent. In Zimbabwe, former Rhodesia, president Robert Mugabe has, starting in the 1990s, targeted white farmers and forcibly seized their property. In some cases, decolonization is hardly possible or impossible because of the importance of the settler population or where the indigenous population is now in the minority; such is the case of the British population of the Cayman Islands and the Russian population of Kazakhstan, as well as the settler societies of North America.

The Psychology of dependence and decolonizing the mind

Critics of the continued dependence of many former colonies on the developed world sometimes offer this as a defense of colonialism, or of neocolonialism as a necessary evil. The inability of countries in the former colonial empires to create stable, viable economies and democratic systems is blamed on ancient tribal animosities, congenital inability to order their affairs and on a psychology of dependency. In response, others point to how the artificial creation of boundaries, together with the way in which colonial powers played different communities off against each other to justify their rule maintaining peace, as the causes of tension, conflict and authoritarian responses. They point out that the way in which Africa and Africans are depicted in works of fiction, too, perpetuates stereotypes of dependency, primitiveness, tribalism and a copy-cat rather than creative mentality. Those who argue that continued dependency stems in part from a psychology that informs an attitude of racial, intellectual or cultural inferiority are also speaking of the need to decolonize the mind, an expressed used by Ngugi wa Thiong’o. He argued that much that is written about the problems of Africa perpetuates the idea that primitive tribalism lies at their root:

The study of the African realities has for too long been seen in terms of tribes. Whatever happens in Kenya, Uganda, Malawi is because of Tribe A versus Tribe B. Whatever erupts in Zaire, Nigeria, Liberia, Zambia is because of the traditional enmity between Tribe D and Tribe C. A variation of the same stock interpretation is Moslem versus Christian, or Catholic versus Protestant where a people does not easily fall into ‘tribes’. Even literature is sometimes evaluated in terms of the ‘tribal’ origins of the authors or the ‘tribal’ origins and composition of the characters in a given novel or play. This misleading stock interpretation of the African realities has been popularized by the western media which likes to deflect people from seeing that imperialism is still the root cause of many problems in Africa. Unfortunately some African intellectuals have fallen victims—a few incurably so—to that scheme and they are unable to see the divide-and-rule colonial origins of explaining any differences of intellectual outlook or any political clashes in terms of the ethnic origins of the actors …[10]

The Future of the Nation State

Since 1945 and the establishment of the United Nations, the nation-state has been accepted as the ideal form of political organization. In theory, each nation state regardless of size is equal, thus all states have one vote in the United Nations General Assembly. Privilege, however, was built into the UN system as a safeguard by the great powers after World War II, who gave the victors permanent membership and a veto in the United Nations Security Council. Inevitably, the Permanent Five have often acted in their own interests. Non-permanent member states, too, often vote to protect their own interests. Arguably, only a world in which all people regard their interests as inseparable from those of others will be able to overcome injustice, end poverty, war and inequality between people. Few have stopped to ask, as new nation states gained their independence and joined the UN, whether becoming a nation-state was really in their peoples' best interests. Some very small states have been formed. Might some states be more economically viable in partnership with others within con-federal associations. Should some nation-states have been formed in the shape and form they have taken, often a legacy of colonialism when little attention was given to issues of community cohesiveness or traditional community identities or boundaries? Some suggest that only a type of world government—in which the interests of humanity, of the planet, of its ecology and of its non-human inhabitants are considered—can hope to solve the problems that confront the world globally and people locally where they live. Devolution of governance downwards might create more participatory, sustainable communities; devolution upwards to supra-national agencies might overcome the problem of self-interest that causes nations to perpetuate their wealth and power at the expense of others.

A Religious perspective

Some Christians believe that God's intent for the world is a single-nation, into which the wealth, wisdom—but not the weapons—of the many nations will flow, based on an interpretation of Revelations 21: 26. Then the Messianic era of peace and justice promised by such passages as Isaiah 11 and 65 will finally dawn. From a neo-conservative political perspective, Francis Fukuyama has argued that what he calls the "liberal society" is the apex of human achievement. In and between such societies, he argues, war will diminish and eventually fade away. This represents the maturation of human consciousness. Central to Fukuyama's scenario is the concept of thymos which may be described as "an innate human sense of justice," as the "psychological seat of all the noble virtues like selflessness, idealism, morality, self-sacrifice, courage and honorability"[11] In Plato, it was linked with "a good political order".[12] Thymos enables us to firstly assign worth to ourselves, and to feel indignant when our worth is devalued then to assign "worth to other people" and to feel "anger on behalf of others."[13] As an essential feature of what he means by "liberal societies," thymos would result in the end of global injustice, inequality and violent resolution of disputes. Indeed, history as we know it, which mainly comprises the story of wars between and within states, would end; thenceforth, international relations would deal with "the solving of technological problems, environmental concerns and the satisfaction of sophisticated consumer demands."[14] This converging of religious and non-religious thinking about what type of world humans might succeed in constructing suggests that the human conscience will ultimately not tolerate the perpetuation of injustice, the continuation of violence and of inequality between people.

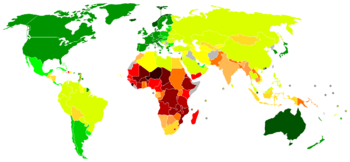

Charts of the Independences

In this chronological overview, not every date is indisputably the decisive moment. Often, the final phase, independence, is mentioned here, though there may be years of autonomy before, e.g. as an Associated State under the British crown.

Furthermore, note that some cases have been included that were not strictly colonized but were rather protectorates, co-dominiums or leases. Changes subsequent to decolonization are usually not included; nor is the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

Eighteenth and nineteenth centuries

| Year | Colonizer | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 1776 | Great Britain | The 13 original colonies of the United States declare independence a year after their insurrection begins. |

| 1783 | Great Britain | The British Crown recognizes the independence of the United States. |

| 1803 | France | Via the Louisiana purchase, the last French territories in North America are handed over to the United States. |

| 1804 | France | Haiti declares independence, the first non-white nation to emancipate itself from European rule. |

| 1808 | Portugal | Brazil, the largest Portuguese colony, achieves a greater degree of autonomy after the exiled king of Portugal establishes residence there. After he returns home in 1821, his son and regent declares an independent "Empire" in 1822. |

| 1813 | Spain | Paraguay becomes independent. |

| 1816 | Spain | Argentina declares independence (Uruguay, then included in Argentina, would achieve its independence in 1828, after periods of Brazilian occupation and of federation with Argentina) |

| 1818 | Spain | Second and final declaration of independence of Chile |

| 1819 | Spain | New Granada attains independence as Gran Colombia (later to become the independent states of Colombia, Ecuador, Panama and Venezuela). |

| 1821 | Spain | The Dominican Republic (then Santo Domingo), Nicaragua, Honduras, Guatemala, El Salvador and Costa Rica all declare independence; Venezuela and Mexico both achieve independence. |

| 1822 | Spain | Ecuador attains independence from Spain (and independence from Colombia 1830). |

| 1824 | Spain | Peru and Bolivia attain independence. |

| 1847 | United States | Liberia becomes a free and independent African state. |

| 1865 | Spain | The Dominican Republic gains its final independence after four years as a restored colony. |

| 1868 | Spain | Cuba declares independence and is reconquered; taken by the United States in 1898; governed under U.S. military administration until 1902. |

| 1898 | Spain | The Philippines declares independence but is taken by the United States in 1899; governed under U.S. military and then civilian administration until 1934. |

Twentieth century

| Year | Colonizer | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 1919 | United Kingdom | End of the protectorate over Afghanistan, when Britain accepts the presence of a Soviet ambassador in Kabul. |

| 1921 | China | The strong empire loses all control over Outer Mongolia but retains the larger, progressively sinified, Inner Mongolia), which has been granted autonomy in 1912 (as well as Tibet), and now becomes a popular republic and, as of 1924, a de facto satellite of the USSR. Formal recognition of Mongolia will follow in 1945. |

| 1922 | United Kingdom | In Ireland, following insurgency by the IRA, most of Ireland separates from the United Kingdom as the Irish Free State, reversing 800 years of British presence. Northern Ireland, the northeast area of the island, remains within the United Kingdom. |

| 1923 | United Kingdom | End of the de facto protectorate over Nepal which was never truly colonized. |

| 1930 | United Kingdom | The United Kingdom returns the leased port territory at Weihaiwei to China, the first episode of decolonization in East Asia. |

| 1931 | United Kingdom | The Statute of Westminster grants virtually full independence to Canada, New Zealand, Newfoundland, the Irish Free State, the Commonwealth of Australia, and the Union of South Africa, when it declares the British Parliament incapable of passing law over these former colonies without their own consent. |

| 1932 | United Kingdom | Ends League of Nations Mandate over Iraq. Britain continues to station troops in the country and influence the Iraqi government until 1958. |

| 1934 | United States | Makes the Philippine Islands a Commonwealth. Abrogates Platt Amendment, which gave it direct authority to intervene in Cuba. |

| 1941 | France | Lebanon declares independence, effectively ending the French mandate (previously together with Syria) - it is recognized in 1943. |

| 1941 | Italy | Ethiopia, Eritrea & Tigray (appended to it), and the Italian part of Somalia are liberated by the Allies after an uneasy occupation of Ethiopia since 1935-1936, and no longer joined as one colonial federal state; the Ogaden desert (disputed by Somalia) remains under British military control until 1948. |

From World War II to the present

| Year | Colonizer | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 1945 | Japan | After surrender of Japan, North Korea was reigned by Soviet Union and South Korea was reigned by United States. |

| Japan | The Republic of China possesses Taiwan | |

| France | Vietnam declares independence but only to be recognized nine years later | |

| 1946 | United States | The sovereignty of the Philippines is recognized by the United States, which conquered the islands during the Philippine-American War. But, the United States continues to station troops in the country as well as influence the Philippine government and economy (through the Bell Trade Act) until the fall of Marcos in 1986, which allowed Filipinos to author a genuinely Filipino constitution. |

| United Kingdom | The former emirate of Transjordan (present-day Jordan) becomes an independent Hashemite kingdom when Britain relinquishes UN trusteeship. | |

| 1947 | United Kingdom | The Republic of India and Muslim State of Pakistan (including present-day Bangladesh) achieve direct independence in an attempt to separate the native Hindus officially from secular and Muslim parts of former British India. The non-violent independence movement led by M. K. Gandhi has been inspirational for other non-violent protests around the world, including the Civil Rights Movement in the United States. |

| 1948 | United Kingdom | In the Far East, Burma and Ceylon (Sri Lanka) become independent. In the Middle East, Israel becomes independent less than a year after the British government withdraws from the Palestine Mandate; the remainder of Palestine becomes part of the Arab states of Egypt and Transjordan. |

| United States | Republic of Korea was established. | |

| Soviet Union | Democratic People's Republic of Korea was established. | |

| 1949 | France | Laos becomes independent. |

| The Netherlands | Independence of United States of Indonesia is recognized by United Nations and subsequently overthrown by the Republic of Indonesia led by Sukarno | |

| 1951 | Italy | Libya becomes an independent kingdom. |

| 1952 | United States | Puerto Rico in the Antilles becomes a self governing Commonwealth associated to the US. |

| 1953 | France | France recognizes Cambodia's independence. |

| 1954 | France | Vietnam's independence recognized, though the nation is partitioned. The Pondichery enclave is incorporated into India. Beginning of the Algerian War of Independence |

| United Kingdom | The United Kingdom withdraws from the last part of Egypt it controls: the Suez Canal zone. | |

| 1956 | United Kingdom | Anglo-Egyptian Sudan becomes independent. |

| France | Tunisia and the sherifian kingdom of Morocco in the Maghreb achieve independence. | |

| Spain | Spain-controlled areas in Morroco become independent. | |

| 1957 | United Kingdom | Ghana becomes independent, initiating the decolonization of sub-Saharan Africa. |

| United Kingdom | The Federation of Malaya becomes independent. | |

| 1958 | France | Guinea on the coast of West-Africa is granted independence. |

| United States | Signing the Alaska Statehood Act by Dwight D. Eisenhower, granting Alaska the possibility of the equal rights of statehood | |

| United Kingdom | UN trustee Britain withdraws from Iraq, which becomes an independent Hashemite Kingdom (like Jordan, but soon to become a republic through the first of several coups d'états. | |

| 1960 | United Kingdom | Nigeria, British Somaliland (present-day Somalia), and most of Cyprus become independent, though the UK retains sovereign control over Akrotiri and Dhekelia. |

| France | Benin (then Dahomey), Upper Volta (present-day Burkina Faso), Cameroon, Chad, Congo-Brazzaville, Côte d'Ivoire, Gabon, the Mali Federation (split the same year into present-day Mali and Senegal), Mauritania, Niger, Togo and the Central African Republic (the Oubangui Chari) and Madagascar all become independent. | |

| Belgium | The Belgian Congo (also known as Congo-Kinshasa, later renamed Zaire and presently the Democratic Republic of the Congo), becomes independent. | |

| 1961 | United Kingdom | Tanganyika (formerly a German colony under UK trusteeship, merged to federal Tanzania in 1964 with the island of Zanzibar, formerly a proper British colony wrested from the Omani sultanate); Sierra Leone, Kuwait and British Cameroon become independent. South Africa declares independence. |

| Portugal | The former coastal enclave colonies of Goa, Daman and Diu are taken over by India. | |

| 1962 | United Kingdom | Uganda in Africa, and Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago in the Caribbean, achieve independence. |

| France | End of Algerian War of Independence, Algeria becomes independent. | |

| Belgium | Rwanda and Burundi (then Urundi) attain independence through the ending of the Belgian trusteeship. | |

| New Zealand | The South Sea UN trusteeship over the Polynesian kingdom of Western Samoa (formerly German Samoa and nowadays called just Samoa) is relinquished. | |

| 1963 | United Kingdom | Kenya becomes independent. |

| United Kingdom | Singapore, together with Sarawak and Sabah on North Borneo, form Malaysia with the peninsular Federation of Malaya. | |

| 1964 | United Kingdom | Northern Rhodesia declares independence as Zambia and Malawi, formerly Nyasaland does the same, both from the United Kingdom. The Mediterranean island of Malta becomes independent. |

| 1965 | United Kingdom | Southern Rhodesia (the present Zimbabwe) declares independence as Rhodesia, a second Apartheid regime, but is not recognized. Gambia is recognized as independent. The British protectorate over the Maldives archipelago in the Indian Ocean is ended. |

| 1966 | United Kingdom | In the Caribbean, Barbados and Guyana; and in Africa, Botswana (then Bechuanaland) and Lesotho become independent. |

| 1967 | United Kingdom | On the Arabian peninsula, Aden colony becomes independent as South Yemen, to be united with formerly Ottoman North Yemen in 1990-1991. |

| 1968 | United Kingdom | Mauritius and Swaziland achieve independence. |

| Portugal | After nine years of organized guerrilla resistance, most of Guinea-Bissau comes under native control. | |

| Spain | Equatorial Guinea (then Rio Muni) is made independent. | |

| Australia | Relinquishes UN trusteeship (nominally shared by the United Kingdom and New Zealand) of Nauru in the South Sea. | |

| 1971 | United Kingdom | Fiji and Tonga in the South Sea are given independence; South Asia East Pakistan achieves independence with the help of India. |

| United Kingdom | Bahrain, Qatar, Oman and seven Trucial States (the same year, six federated together as United Arab Emirates and the seventh, Ras al-Kaimah, joined soon after) become independent Arab monarchies in the Persian Gulf as the British protectorates are lifted. | |

| 1973 | United Kingdom | The Bahamas are granted independence. |

| Portugal | Guerrillas unilaterally declare independence in the Southeastern regions of Guinea-Bissau. | |

| 1974 | United Kingdom | Grenada in the Caribbean becomes independent. |

| Portugal | Guinea-Bissau on the coast of West-Africa is recognized as independent by Portugal. | |

| 1975 | France | The Comoros archipelago in the Indian Ocean off the coast of Africa is granted independence. |

| Portugal | Angola, Mozambique and the island groups of Cape Verde and São Tomé and Príncipe, all four in Africa, achieve independence. East Timor declares independence, but is subsequently occupied and annexed by Indonesia nine days later. | |

| The Netherlands | Suriname (then Dutch Guiana) becomes independent. | |

| Australia | Released from trusteeship, Papua New Guinea gains independence. | |

| 1976 | United Kingdom | Seychelles archipelago in the Indian Ocean off the African coast becomes independent (one year after granting of self-rule). |

| Spain | The Spanish colonial rule de facto terminated over the Western Sahara (then Rio de Oro), when the territory was passed on to and partitioned between Mauritania and Morocco (which annexes the entire territory in 1979), rendering the declared independence of the Saharawi Arab Democratic Republic ineffective to the present day. Since Spain did not have the right to give away Western Sahara, under international law the territory is still under Spanish administration. The de facto administrator is however Morocco. | |

| 1977 | France | French Somaliland, also known as Afar & Issa-land (after its main tribal groups), the present Djibouti, is granted independence. |

| 1978 | United Kingdom | Dominica in the Caribbean and the Solomon Islands, as well as Tuvalu (then the Ellice Islands), all in the South Sea, become independent. |

| 1979 | United States | Returns the Panama Canal Zone (held under a regime sui generis since 1903) to the republic of Panama. |

| United Kingdom | The Gilbert Islands (present-day Kiribati) in the South Sea as well as Saint Vincent and the Grenadines and Saint Lucia in the Caribbean become independent. | |

| 1980 | United Kingdom | Zimbabwe (then [Southern] Rhodesia), already independent de facto, becomes formally independent. The joint Anglo-French colony of the New Hebrides becomes the independent island republic of Vanuatu. |

| 1981 | United Kingdom | Belize (then British Honduras) and Antigua & Barbuda become independent. |

| 1983 | United Kingdom | Saint Kitts and Nevis (an associated state since 1963) becomes independent. |

| 1984 | United Kingdom | Brunei sultanate on Borneo becomes independent. |

| 1990 | South Africa | Namibia becomes independent from South Africa. |

| United States | The UN Security Council gives final approval to end the U.S. Trust Territory of the Pacific (dissolved already in 1986), finalizing the independence of the Marshall Islands and the Federated States of Micronesia, having been a colonial possession of the empire of Japan before UN trusteeship. | |

| 1991 | United States | U.S. forces withdraw from Subic Bay and Clark Air Base in the Philippines ending major U.S. military presence, which lasted for almost a century. |

| 1994 | United States | Palau (after a transitional period as a Republic since 1981, and before part of the U.S. Trust territory of the Pacific) becomes independent from its former trustee, having been a mandate of the Japanese Empire before UN trusteeship. |

| 1997 | United Kingdom | The sovereignty of Hong Kong is transferred to China. |

| 1999 | Portugal | The sovereignty of Macau is transferred to China on schedule. It is the last in a series of coastal enclaves that militarily stronger powers had obtained through treaties from the Chinese Empire. Like Hong Kong, it is not organized into the existing provincial structure applied to other provinces of the People's Republic of China, but is guaranteed a quasi-autonomous system of government within the People's Republic of China. |

| 2002 | Indonesia | East Timor formally achieves independence after a transitional UN administration, three years after Indonesia ended its violent quarter-century military occupation of the former Portuguese colony. |

See also

Notes

- ↑ Daniel Philpott. 2001. Revolutions in sovereignty: how ideas shaped modern international relations. Princeton studies in international history and politics. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691057460), 158.

- ↑ Mario Gonzalez and Elizabeth Cook-Lynn. 1999. The politics of hallowed ground: Wounded Knee and the struggle for Indian sovereignty. (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 9780252023545).

- ↑ Devon A. Mihesuah, 2003. Indigenous American women: decolonization, empowerment, activism. Contemporary indigenous issues. (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 9780803232273).

- ↑ This called for fiscal discipline, the privatization of state owned industries, tax reform, de-regularization and liberalization of trade.

- ↑ Kaye Whiteman, 1997. The man who ran Francafrique - French politician Jacques Foccart's role in France's colonization of Africa under the leadership of Charles de Gaulle - Obituary. The National Interest (Fall, 1997). Jacques Foccart, counselor to Charles de Gaulle, Georges Pompidou and Jacques Chirac for African matters, recognized it in 1995. Retrieved August 18, 2008.

- ↑ Mehdi Ben Barka (born 1920, the Moroccan politician, led the left-wing National Union of Popular Forces (UNPF). He disappeared on October 29, 1965. France has declassified some of the files, but Ben Barka's family has stated that these have shed no new light on the affair, and that further efforts must be done.

- ↑ John Kenneth Galbraith. 1994. A journey through economic time: a firsthand view. (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 9780395637517), 159. Chapter 17 discusses "Decolonization and Economic Development," 158-167.

- ↑ Galbraith, 159.

- ↑ Galbraith, 158.

- ↑ Thiong’o Ngugi wa. 1986. Decolonizing the Mind. The Swaraj Foundation. Retrieved August 18, 2008.

- ↑ Francis Fukuyama. 1992. The End of History and the last man. (New York, NY: Free Press. ISBN 9780029109755, 171.

- ↑ Fukuyama, 1992, 169.

- ↑ Fukuyama, 1992, 171.

- ↑ Fukuyama, 1992, 18.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Betts, Raymond F. Decolonization. The making of the contemporary world. London, UK: Rutledge, 1998. ISBN 978-0415186827

- Chinweizu, Onwuchekwa Jemie, and Ihechukwu Madubuike. Toward the decolonization of African literature. Washington, DC: Howard University Press, 1983. ISBN 978-0882581224

- Duara, Prasenjit. Decolonization perspectives from now and then. Rewriting histories. London, UK: Rutledge, 2004. ISBN 0415248418

- Fukuyama, Francis. The end of history and the last man. New York, NY: Free Press, 1992. ISBN 978-0029109755

- Galbraith, John Kenneth. A journey through economic time: a firsthand view. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 1994. ISBN 978-0395637517

- Gonzalez, Mario, and Elizabeth Cook-Lynn. The politics of hallowed ground: Wounded Knee and the struggle for Indian sovereignty. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1999. ISBN 978-0252023545

- Hargreaves, John D. Decolonization in Africa. The Postwar world. London, UK: Longman, 1988. ISBN 978-0582491502

- Memmi, Albert, and Robert Bononno. Decolonization and the decolonized. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0816647347

- Mihesuah, Devon A. Indigenous American women: decolonization, empowerment, activism. Contemporary indigenous issues. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0803232273

- Ngũgĩ wa Thiongʼo. Decolonising the mind: the politics of language in African literature. London, UK: J. Currey, 1986. ISBN 978-0435080167

- Newsom, David D. The imperial mantle the United States, decolonization, and the Third World. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0253108494

- Philpott, Daniel. Revolutions in sovereignty: how ideas shaped modern international relations. Princeton studies in international history and politics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0691057460

- Rothermund, Dietmar. The Routledge companion to decolonization. Routledge companions to history. London, UK: Rutledge, 2006. ISBN 978-0415356329

- Shepard, Todd. The invention of decolonization: the Algerian War and the remaking of France. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0801443602

- Thomas, Martin. European decolonization. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate, 2007. ISBN 0754625680

- Urquhart, Brian. Decolonization and world peace. Tom Slick world peace series. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 1989. ISBN 978-0292738539

- Wilson, Henry S. African decolonization. London, UK: E. Arnold, 1994. ISBN 978-0340559291

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.